Regenerative medicine has come a long way, baby

After a cloned baby sheep, what started as one of the most controversial areas in medicine is now promising to transform it.

The field of regenerative medicine had a shaky start. In 2002, when news spread about the first cloned animal, Dolly the sheep, a raucous debate ensued. Scary headlines and organized opposition groups put pressure on government leaders, who responded by tightening restrictions on this type of research.

Fast forward to today, and regenerative medicine, which focuses on making unhealthy tissues and organs healthy again, is rewriting the code to healing many disorders, though it’s still young enough to be considered nascent. What started as one of the most controversial areas in medicine is now promising to transform it.

Progress in the lab has addressed previous concerns. Back in the early 2000s, some of the most fervent controversy centered around somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), the process used by scientists to produce Dolly. There was fear that this technique could be used in humans, with possibly adverse effects, considering the many medical problems of the animals who had been cloned.

But today, scientists have discovered better approaches with fewer risks. Pioneers in the field are embracing new possibilities for cellular reprogramming, 3D organ printing, AI collaboration, and even growing organs in space. It could bring a new era of personalized medicine for longer, healthier lives - while potentially sparking new controversies.

Engineering tissues from amniotic fluids

Work in regenerative medicine seeks to reverse damage to organs and tissues by culling, modifying and replacing cells in the human body. Scientists in this field reach deep into the mechanisms of diseases and the breakdowns of cells, the little workhorses that perform all life-giving processes. If cells can’t do their jobs, they take whole organs and systems down with them. Regenerative medicine seeks to harness the power of healthy cells derived from stem cells to do the work that can literally restore patients to a state of health—by giving them healthy, functioning tissues and organs.

Modern-day regenerative medicine takes its origin from the 1998 isolation of human embryonic stem cells, first achieved by John Gearhart at Johns Hopkins University. Gearhart isolated the pluripotent cells that can differentiate into virtually every kind of cell in the human body. There was a raging controversy about the use of these cells in research because at that time they came exclusively from early-stage embryos or fetal tissue.

Back then, the highly controversial SCNT cells were the only way to produce genetically matched stem cells to treat patients. Since then, the picture has changed radically because other sources of highly versatile stem cells have been developed. Today, scientists can derive stem cells from amniotic fluid or reprogram patients’ skin cells back to an immature state, so they can differentiate into whatever types of cells the patient needs.

In the context of medical history, the field of regenerative medicine is progressing at a dizzying speed. But for those living with aggressive or chronic illnesses, it can seem that the wheels of medical progress grind slowly.

The ethical debate has been dialed back and, in the last few decades, the field has produced important innovations, spurring the development of whole new FDA processes and categories, says Anthony Atala, a bioengineer and director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine. Atala and a large team of researchers have pioneered many of the first applications of 3D printed tissues and organs using cells developed from patients or those obtained from amniotic fluid or placentas.

His lab, considered to be the largest devoted to translational regenerative medicine, is currently working with 40 different engineered human tissues. Sixteen of them have been transplanted into patients. That includes skin, bladders, urethras, muscles, kidneys and vaginal organs, to name just a few.

These achievements are made possible by converging disciplines and technologies, such as cell therapies, bioengineering, gene editing, nanotechnology and 3D printing, to create living tissues and organs for human transplants. Atala is currently overseeing clinical trials to test the safety of tissues and organs engineered in the Wake Forest lab, a significant step toward FDA approval.

In the context of medical history, the field of regenerative medicine is progressing at a dizzying speed. But for those living with aggressive or chronic illnesses, it can seem that the wheels of medical progress grind slowly.

“It’s never fast enough,” Atala says. “We want to get new treatments into the clinic faster, but the reality is that you have to dot all your i’s and cross all your t’s—and rightly so, for the sake of patient safety. People want predictions, but you can never predict how much work it will take to go from conceptualization to utilization.”

As a surgeon, he also treats patients and is able to follow transplant recipients. “At the end of the day, the goal is to get these technologies into patients, and working with the patients is a very rewarding experience,” he says. Will the 3D printed organs ever outrun the shortage of donated organs? “That’s the hope,” Atala says, “but this technology won’t eliminate the need for them in our lifetime.”

New methods are out of this world

Jeanne Loring, another pioneer in the field and director of the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Scripps Research Institute in San Diego, says that investment in regenerative medicine is not only paying off, but is leading to truly personalized medicine, one of the holy grails of modern science.

This is because a patient’s own skin cells can be reprogrammed to become replacements for various malfunctioning cells causing incurable diseases, such as diabetes, heart disease, macular degeneration and Parkinson’s. If the cells are obtained from a source other than the patient, they can be rejected by the immune system. This means that patients need lifelong immunosuppression, which isn’t ideal. “With Covid,” says Loring, “I became acutely aware of the dangers of immunosuppression.” Using the patient’s own cells eliminates that problem.

Microgravity conditions make it easier for the cells to form three-dimensional structures, which could more easily lead to the growing of whole organs. In fact, Loring's own cells have been sent to the ISS for study.

Loring has a special interest in neurons, or brain cells that can be developed by manipulating cells found in the skin. She is looking to eventually treat Parkinson’s disease using them. The manipulated cells produce dopamine, the critical hormone or neurotransmitter lacking in the brains of patients. A company she founded plans to start a Phase I clinical trial using cell therapies for Parkinson’s soon, she says.

This is the culmination of many years of basic research on her part, some of it on her own cells. In 2007, Loring had her own cells reprogrammed, so there’s a cell line that carries her DNA. “They’re just like embryonic stem cells, but personal,” she said.

Loring has another special interest—sending immature cells into space to be studied at the International Space Station. There, microgravity conditions make it easier for the cells to form three-dimensional structures, which could more easily lead to the growing of whole organs. In fact, her own cells have been sent to the ISS for study. “My colleagues and I have completed four missions at the space station,” she says. “The last cells came down last August. They were my own cells reprogrammed into pluripotent cells in 2009. No one else can say that,” she adds.

Future controversies and tipping points

Although the original SCNT debate has calmed down, more controversies may arise, Loring thinks.

One of them could concern growing synthetic embryos. The embryos are ultimately derived from embryonic stem cells, and it’s not clear to what stage these embryos can or will be grown in an artificial uterus—another recent invention. The science, so far done only in animals, is still new and has not been widely publicized but, eventually, “People will notice the production of synthetic embryos and growing them in an artificial uterus,” Loring says. It’s likely to incite many of the same reactions as the use of embryonic stem cells.

Bernard Siegel, the founder and director of the Regenerative Medicine Foundation and executive director of the newly formed Healthspan Action Coalition (HSAC), believes that stem cell science is rapidly approaching tipping point and changing all of medical science. (For disclosure, I do consulting work for HSAC). Siegel says that regenerative medicine has become a new pillar of medicine that has recently been fast-tracked by new technology.

Artificial intelligence is speeding up discoveries and the convergence of key disciplines, as demonstrated in Atala’s lab, which is creating complex new medical products that replace the body’s natural parts. Just as importantly, those parts are genetically matched and pose no risk of rejection.

These new technologies must be regulated, which can be a challenge, Siegel notes. “Cell therapies represent a challenge to the existing regulatory structure, including payment, reimbursement and infrastructure issues that 20 years ago, didn’t exist.” Now the FDA and other agencies are faced with this revolution, and they’re just beginning to adapt.

Siegel cited the 2021 FDA Modernization Act as a major step. The Act allows drug developers to use alternatives to animal testing in investigating the safety and efficacy of new compounds, loosening the agency’s requirement for extensive animal testing before a new drug can move into clinical trials. The Act is a recognition of the profound effect that cultured human cells are having on research. Being able to test drugs using actual human cells promises to be far safer and more accurate in predicting how they will act in the human body, and could accelerate drug development.

Siegel, a longtime veteran and founding father of several health advocacy organizations, believes this work helped bring cell therapies to people sooner rather than later. His new focus, through the HSAC, is to leverage regenerative medicine into extending not just the lifespan but the worldwide human healthspan, the period of life lived with health and vigor. “When you look at the HSAC as a tree,” asks Siegel, “what are the roots of that tree? Stem cell science and the huge ecosystem it has created.” The study of human aging is another root to the tree that has potential to lengthen healthspans.

The revolutionary science underlying the extension of the healthspan needs to be available to the whole world, Siegel says. “We need to take all these roots and come up with a way to improve the life of all mankind,” he says. “Everyone should be able to take advantage of this promising new world.”

Real-Time Monitoring of Your Health Is the Future of Medicine

Implantable sensors and other surveillance technologies offer tremendous health benefits -- and ethical challenges.

The same way that it's harder to lose 100 pounds than it is to not gain 100 pounds, it's easier to stop a disease before it happens than to treat an illness once it's developed.

In Morris' dream scenario "everyone will be implanted with a sensor" ("…the same way most people are vaccinated") and the sensor will alert people to go to the doctor if something is awry.

Bio-engineers working on the next generation of diagnostic tools say today's technology, such as colonoscopies or mammograms, are reactionary; that is, they tell a person they are sick often when it's too late to reverse course. Surveillance medicine — such as implanted sensors — will detect disease at its onset, in real time.

What Is Possible?

Ever since the Human Genome Project — which concluded in 2003 after mapping the DNA sequence of all 30,000 human genes — modern medicine has shifted to "personalized medicine." Also called, "precision health," 21st-century doctors can in some cases assess a person's risk for specific diseases from his or her DNA. The information enables women with a BRCA gene mutation, for example, to undergo more frequent screenings for breast cancer or to pro-actively choose to remove their breasts, as a "just in case" measure.

But your DNA is not always enough to determine your risk of illness. Not all genetic mutations are harmful, for example, and people can get sick without a genetic cause, such as with an infection. Hence the need for a more "real-time" way to monitor health.

Aaron Morris, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Michigan, wants doctors to be able to predict illness with pinpoint accuracy well before symptoms show up. Working in the lab of Dr. Lonnie Shea, the team is building "a tiny diagnostic lab" that can live under a person's skin and monitor for illness, 24/7. Currently being tested in mice, the Michigan team's porous biodegradable implant becomes part of the body as "cells move right in," says Morris, allowing engineered tissue to be biopsied and analyzed for diseases. The information collected by the sensors will enable doctors to predict disease flareups, such as for cancer relapses, so that therapies can begin well before a person comes out of remission. The technology will also measure the effectiveness of those therapies in real time.

In Morris' dream scenario "everyone will be implanted with a sensor" ("…the same way most people are vaccinated") and the sensor will alert people to go to the doctor if something is awry.

While it may be four or five decades before Morris' sensor becomes mainstream, "the age of surveillance medicine is here," says Jamie Metzl, a technology and healthcare futurist who penned Hacking Darwin: Genetic Engineering and the Future of Humanity. "It will get more effective and sophisticated and less obtrusive over time," says Metzl.

Already, Google compiles public health data about disease hotspots by amalgamating individual searches for medical symptoms; pill technology can digitally track when and how much medication a patient takes; and, the Apple watch heart app can predict with 85-percent accuracy if an individual using the wrist device has Atrial Fibrulation (AFib) — a condition that causes stroke, blood clots and heart failure, and goes undiagnosed in 700,000 people each year in the U.S.

"We'll never be able to predict everything," says Metzl. "But we will always be able to predict and prevent more and more; that is the future of healthcare and medicine."

Morris believes that within ten years there will be surveillance tools that can predict if an individual has contracted the flu well before symptoms develop.

At City College of New York, Ryan Williams, assistant professor of biomedical engineering, has built an implantable nano-sensor that works with a florescent wand to scope out if cancer cells are growing at the implant site. "Instead of having the ovary or breast removed, the patient could just have this [surveillance] device that can say 'hey we're monitoring for this' in real-time… [to] measure whether the cancer is maybe coming back,' as opposed to having biopsy tests or undergoing treatments or invasive procedures."

Not all surveillance technologies that are being developed need to be implanted. At Case Western, Colin Drummond, PhD, MBA, a data scientist and assistant department chair of the Department of Biomedical Engineering, is building a "surroundable." He describes it as an Alexa-style surveillance system (he's named her Regina) that will "tell" the user, if a need arises for medication, how much to take and when.

Bioethical Red Flags

"Everyone should be extremely excited about our move toward what I call predictive and preventive health care and health," says Metzl. "We should also be worried about it. Because all of these technologies can be used well and they can [also] be abused." The concerns are many layered:

Discriminatory practices

For years now, bioethicists have expressed concerns about employee-sponsored wellness programs that encourage fitness while also tracking employee health data."Getting access to your health data can change the way your employer thinks about your employability," says Keisha Ray, assistant professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth). Such access can lead to discriminatory practices against employees that are less fit. "Surveillance medicine only heightens those risks," says Ray.

Who owns the data?

Surveillance medicine may help "democratize healthcare" which could be a good thing, says Anita Ho, an associate professor in bioethics at both the University of California, San Francisco and at the University of British Columbia. It would enable easier access by patients to their health data, delivered to smart phones, for example, rather than waiting for a call from the doctor. But, she also wonders who will own the data collected and if that owner has the right to share it or sell it. "A direct-to-consumer device is where the lines get a little blurry," says Ho. Currently, health data collected by Apple Watch is owned by Apple. "So we have to ask bigger ethical questions in terms of what consent should be required" by users.

Insurance coverage

"Consumers of these products deserve some sort of assurance that using a product that will predict future needs won't in any way jeopardize their ability to access care for those needs," says Hastings Center bioethicist Carolyn Neuhaus. She is urging lawmakers to begin tackling policy issues created by surveillance medicine, now, well ahead of the technology becoming mainstream, not unlike GINA, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 -- a federal law designed to prevent discrimination in health insurance on the basis of genetic information.

And, because not all Americans have insurance, Ho wants to know, who's going to pay for this technology and how much will it cost?

Trusting our guts

Some bioethicists are concerned that surveillance technology will reduce individuals to their "risk profiles," leaving health care systems to perceive them as nothing more than a "bundle of health and security risks." And further, in our quest to predict and prevent ailments, Neuhaus wonders if an over-reliance on data could damage the ability of future generations to trust their gut and tune into their own bodies?

It "sounds kind of hippy-dippy and feel-goodie," she admits. But in our culture of medicine where efficiency is highly valued, there's "a tendency to not value and appreciate what one feels inside of their own body … [because] it's easier to look at data than to listen to people's really messy stories of how they 'felt weird' the other day. It takes a lot less time to look at a sheet, to read out what the sensor implanted inside your body or planted around your house says."

Ho, too, worries about lost narratives. "For surveillance medicine to actually work we have to think about how we educate clinicians about the utility of these devices and how to how to interpret the data in the broader context of patients' lives."

Over-diagnosing

While one of the goals of surveillance medicine is to cut down on doctor visits, Ho wonders if the technology will have the opposite effect. "People may be going to the doctor more for things that actually are benign and are really not of concern yet," says Ho. She is also concerned that surveillance tools could make healthcare almost "recreational" and underscores the importance of making sure that the goals of surveillance medicine are met before the technology is unleashed.

"We can't just assume that any of these technologies are inherently technologies of liberation."

AI doesn't fix existing healthcare problems

"Knowing that you're going to have a fall or going to relapse or have a disease isn't all that helpful if you have no access to the follow-up care and you can't afford it and you can't afford the prescription medication that's going to ward off the onset," says Neuhaus. "It may still be worth knowing … but we can't fool ourselves into thinking that this technology is going to reshape medicine in America if we don't pay attention to … the infrastructure that we don't currently have."

Race-based medicine

How surveillances devices are tested before being approved for human use is a major concern for Ho. In recent years, alerts have been raised about the homogeneity of study group participants — too white and too male. Ho wonders if the devices will be able to "accurately predict the disease progression for people whose data has not been used in developing the technology?" COVID-19 has killed Black people at a rate 2.5 time greater than white people, for example, and new, virtual clinical research is focused on recruiting more people of color.

The Biggest Question

"We can't just assume that any of these technologies are inherently technologies of liberation," says Metzl.

Especially because we haven't yet asked the 64-thousand dollar question: Would patients even want to know?

Jenny Ahlstrom is an IT professional who was diagnosed at 43 with multiple myeloma, a blood cancer that typically attacks people in their late 60s and 70s and for which there is no cure. She believes that most people won't want to know about their declining health in real time. People like to live "optimistically in denial most of the time. If they don't have a problem, they don't want to really think they have a problem until they have [it]," especially when there is no cure. "Psychologically? That would be hard to know."

Ahlstrom says there's also the issue of trust, something she experienced first-hand when she launched her non-profit, HealthTree, a crowdsourcing tool to help myeloma patients "find their genetic twin" and learn what therapies may or may not work. "People want to share their story, not their data," says Ahlstrom. "We have been so conditioned as a nation to believe that our medical data is so valuable."

Metzl acknowledges that adoption of new technologies will be uneven. But he also believes that "over time, it will be abundantly clear that it's much, much cheaper to predict and prevent disease than it is to treat disease once it's already emerged."

Beyond cost, the tremendous potential of these technologies to help us live healthier and longer lives is a game-changer, he says, as long as we find ways "to ultimately navigate this terrain and put systems in place ... to minimize any potential harms."

How Smallpox Was Wiped Off the Planet By a Vaccine and Global Cooperation

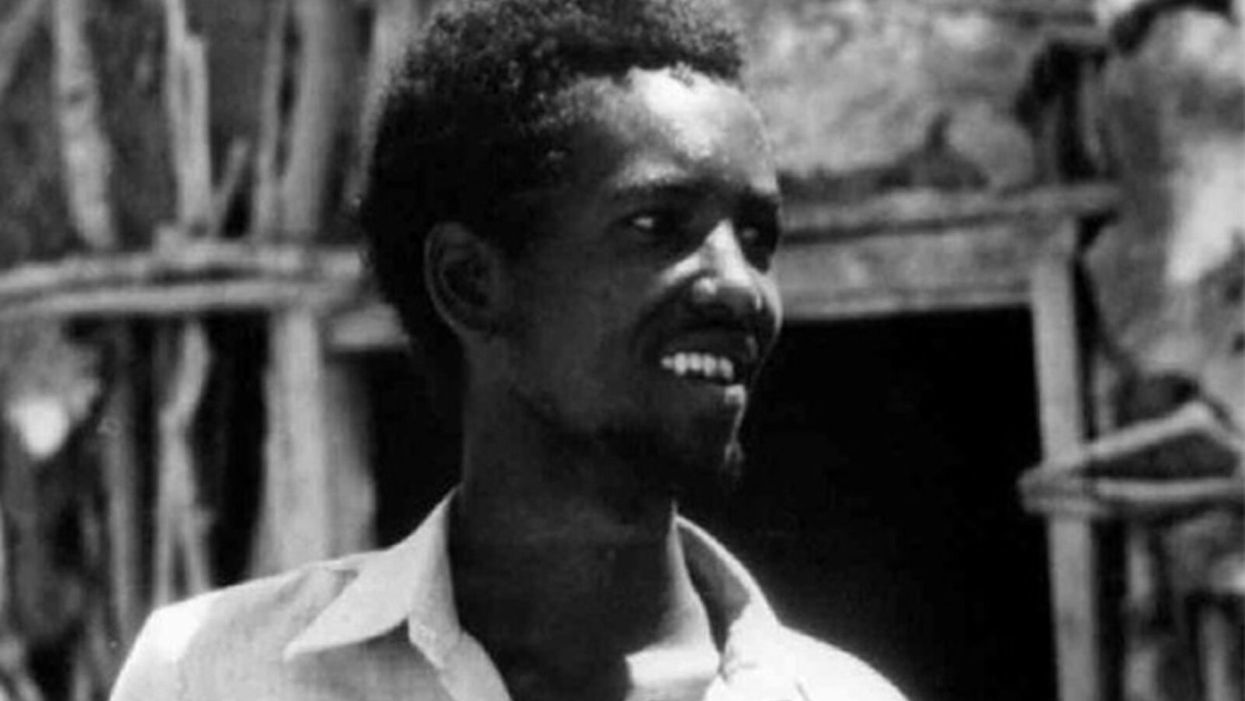

The world's last recorded case of endemic smallpox was in Ali Maow Maalin, of Merka, Somalia, in October 1977. He made a full recovery.

For 3000 years, civilizations all over the world were brutalized by smallpox, an infectious and deadly virus characterized by fever and a rash of painful, oozing sores.

Doctors had to contend with wars, floods, and language barriers to make their campaign a success.

Smallpox was merciless, killing one third of people it infected and leaving many survivors permanently pockmarked and blind. Although smallpox was more common during the 18th and 19th centuries, it was still a leading cause of death even up until the early 1950s, killing an estimated 50 million people annually.

A Primitive Cure

Sometime during the 10th century, Chinese physicians figured out that exposing people to a tiny bit of smallpox would sometimes result in a milder infection and immunity to the disease afterward (if the person survived). Desperate for a cure, people would huff powders made of smallpox scabs or insert smallpox pus into their skin, all in the hopes of getting immunity without having to get too sick. However, this method – called inoculation – didn't always work. People could still catch the full-blown disease, spread it to others, or even catch another infectious disease like syphilis in the process.

A Breakthrough Treatment

For centuries, inoculation – however imperfect – was the only protection the world had against smallpox. But in the late 18th century, an English physician named Edward Jenner created a more effective method. Jenner discovered that inoculating a person with cowpox – a much milder relative of the smallpox virus – would make that person immune to smallpox as well, but this time without the possibility of actually catching or transmitting smallpox. His breakthrough became the world's first vaccine against a contagious disease. Other researchers, like Louis Pasteur, would use these same principles to make vaccines for global killers like anthrax and rabies. Vaccination was considered a miracle, conferring all of the rewards of having gotten sick (immunity) without the risk of death or blindness.

Scaling the Cure

As vaccination became more widespread, the number of global smallpox deaths began to drop, particularly in Europe and the United States. But even as late as 1967, smallpox was still killing anywhere from 10 to 15 million people in poorer parts of the globe. The World Health Assembly (a decision-making body of the World Health Organization) decided that year to launch the first coordinated effort to eradicate smallpox from the planet completely, aiming for 80 percent vaccine coverage in every country in which the disease was endemic – a total of 33 countries.

But officials knew that eradicating smallpox would be easier said than done. Doctors had to contend with wars, floods, and language barriers to make their campaign a success. The vaccination initiative in Bangladesh proved the most challenging, due to its population density and the prevalence of the disease, writes journalist Laurie Garrett in her book, The Coming Plague.

In one instance, French physician Daniel Tarantola on assignment in Bangladesh confronted a murderous gang that was thought to be spreading smallpox throughout the countryside during their crime sprees. Without police protection, Tarantola confronted the gang and "faced down guns" in order to immunize them, protecting the villagers from repeated outbreaks.

Because not enough vaccines existed to vaccinate everyone in a given country, doctors utilized a strategy called "ring vaccination," which meant locating individual outbreaks and vaccinating all known and possible contacts to stop an outbreak at its source. Fewer than 50 percent of the population in Nigeria received a vaccine, for example, but thanks to ring vaccination, it was eradicated in that country nonetheless. Doctors worked tirelessly for the next eleven years to immunize as many people as possible.

The World Health Organization declared smallpox officially eradicated on May 8, 1980.

A Resounding Success

In November 1975, officials discovered a case of variola major — the more virulent strain of the smallpox virus — in a three-year-old Bangladeshi girl named Rahima Banu. Banu was forcibly quarantined in her family's home with armed guards until the risk of transmission had passed, while officials went door-to-door vaccinating everyone within a five-mile radius. Two years later, the last case of variola major in human history was reported in Somalia. When no new community-acquired cases appeared after that, the World Health Organization declared smallpox officially eradicated on May 8, 1980.

Because of smallpox, we now know it's possible to completely eliminate a disease. But is it likely to happen again with other diseases, like COVID-19? Some scientists aren't so sure. As dangerous as smallpox was, it had a few characteristics that made eradication possibly easier than for other diseases. Smallpox, for instance, has no animal reservoir, meaning that it could not circulate in animals and resurge in a human population at a later date. Additionally, a person who had smallpox once was guaranteed immunity from the disease thereafter — which is not the case for COVID-19.

In The Coming Plague, Japanese physician Isao Arita, who led the WHO's Smallpox Eradication Unit, admitted to routinely defying orders from the WHO, mobilizing to parts of the world without official approval and sometimes even vaccinating people against their will. "If we hadn't broken every single WHO rule many times over, we would have never defeated smallpox," Arita said. "Never."

Still, thanks to the life-saving technology of vaccines – and the tireless efforts of doctors and scientists across the globe – a once-lethal disease is now a thing of the past.