Roald Dahl lost a child to measles. Here's what he has to say about the new outbreaks.

Olivia Dahl, shortly before her death from measles in 1962.

In 1962, the world was a remarkably different place: Neil Armstrong had yet to take his first steps on the lunar surface, John F. Kennedy was serving as president of the United States, and the Beatles were still a few years away from superstardom, having just recorded their first single.

The word “measles” was also a household name. Measles, which still exists in parts of the world today, is a highly contagious viral infection that typically causes fever, cough, muscle pain, fatigue, and a distinctive red rash. Measles was so pervasive around the world in 1962 that most children had gotten sick with it before the age of fifteen—but even though it was common, it was far from harmless. Measles killed around 400 to 500 people per year in the United States, and approximately 2.6 million people each year worldwide. Countless others suffered severe complications from measles, such as permanent blindness.

Tragedy hits home

Author Roald Dahl at his Buckinghamshire home with Olivia, daughter Chantal, and wife Patricia Neal in 1960.

Ben Martin / Getty Images

That year, British author Roald Dahl was beginning to make a name for himself, having just published his best-selling book James and the Giant Peach. Dahl, who would go on to write some of the most well-loved children’s books of the century, lived in southern England with his wife and three children. One day, Dahl and his wife, actress Patricia Neal, received word that there was an outbreak of measles at his daughters’ school.

While some parents quarantined their children, many others also considered measles a harmless childhood disease. Neal later recalled in her autobiography that a family member had advised her to “let the girls get measles,” thinking it would strengthen their immune systems and be “good for them.” Reluctantly, Dahl and Neal let their two school-aged children, Olivia and Chantal, continue school. Olivia, then aged seven, fell sick with the measles not long after that.

Neither Dahl nor Neal were terribly concerned about Olivia’s infection. Dahl would write later that it seemed to be taking its “usual course,” and the two would read and spend time together while Olivia rested. After a few days of fever and fatigue, Dahl wrote, Olivia seemed like she was “well on the road to recovery.”

But one afternoon, as the two sat on Olivia’s bed making animals out of pipe cleaners, Dahl noticed that Olivia’s “fingers and her mind were not working together.” When Dahl asked how she was feeling, Olivia replied, “I feel all sleepy.”

Within an hour, Dahl wrote, Olivia was unconscious. Within 12 hours, she was dead.

Olivia died of measles encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain caused by an infection. Approximately 1 in 1,000 people infected with measles develop encephalitis, and of those who develop it, between 10 and 20 percent will die.

Dahl was overcome with grief and wracked with guilt for being unable to prevent his daughter’s death. Mourning, Dahl threw himself into his writing and, in his spare time, spent hours lovingly constructing a rock garden on Olivia’s grave in a local churchyard.

After Olivia’s death, Dahl wrote sixteen novels and several collections of short stories, including Matilda, Fantastic Mr. Fox, and Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, which garnered him worldwide acclaim. His most influential piece of writing, however, wasn’t written until 1986.

A father's plea

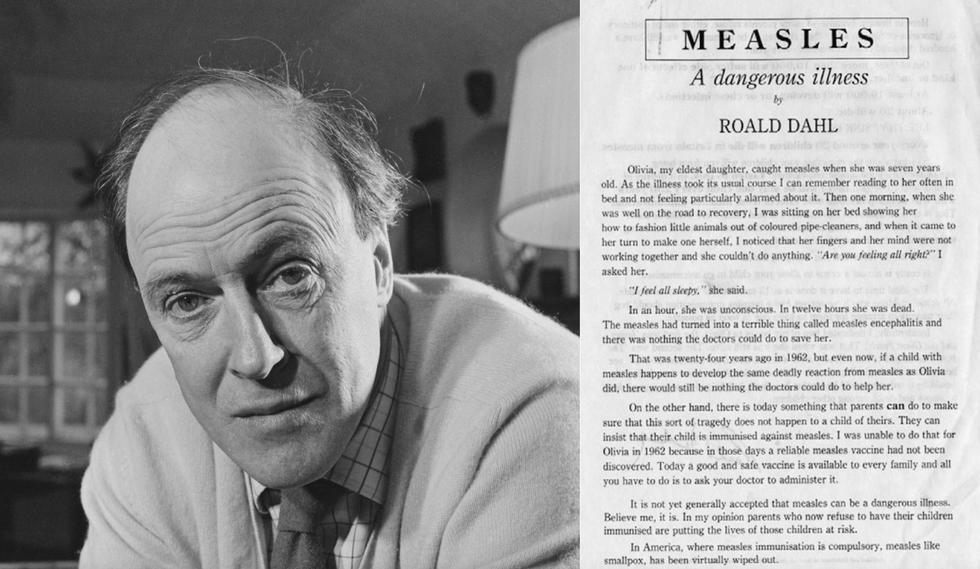

Roald Dahl and the open letter he wrote in 1986, encouraging parents to vaccinate their children against measles.

By 1986, measles was no longer the global health threat that it had been in the 1960s, thanks to a measles vaccine that became available just one year after Olivia had died. Still, in the United Kingdom alone, approximately 80,000 people every year were infected with measles. This bothered Dahl, especially since measles rates in the United States had dropped by 98 percent compared to pre-vaccine years. “Why do we have so much measles in Britain when the Americans have virtually gotten rid of it?,” Dahl was reported to have said.

So Dahl set out to prevent a tragedy like Olivia’s from happening again. With encouragement from several prominent public health activists, Dahl wrote an open letter addressed to parents in the UK. The letter recounted his daughter’s death from encephalitis and begged parents to protect their own children from measles:

“...there is today something that parents can do to make sure that this sort of tragedy does not happen to a child of theirs. They can insist that their child is immunised [sic] against measles. I was unable to do that for Olivia in 1962 because in those days a reliable measles vaccine had not been discovered. Today a good and safe vaccine is available to every family and all you have to do is to ask your doctor to administer it.”

Dahl went on to say that although many parents still viewed measles as a harmless illness, he knew from experience that it was not. Measles was capable of causing disability and death, Dahl wrote, whereas a child had a better chance of “choking on a chocolate bar” than developing any serious complication from the vaccine. Dahl ended his letter by saying how happy he knew Olivia would be “if only she could know that her death had helped to save a good deal of illness and death among other children.”

Dahl’s letter was published in early 1986 and distributed to local healthcare workers, schools, and to parents of children who were particularly at risk. As the letter circulated, vaccination rates continued to climb year after year.

Thirty-one years after Dahl’s letter was published, and 55 years after Olivia’s death, the World Health Organization declared in 2017 that measles had officially been eradicated for the first time in the UK thanks to high rates of vaccination.

A small step back

As vaccination rates decline, measles is now making a strong comeback in the United States and elsewhere.

Getty Images

Today, vaccination rates for the measles are in decline, and countries like the UK and the US, who had once eradicated measles completely, are now seeing a comeback. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported that between December 1, 2023 and January 23, 2024, 23 cases of measles had been confirmed across multiple states. The majority of these cases, they reported, were among children and adolescents who had traveled internationally and had not yet been vaccinated even though they were eligible to do so.

Roald Dahl passed away in 1990, but fortunately, his writing continues to live on. While readers can explore fantastical worlds through his novels and short stories, they can also look back to a reality when tragic deaths like Olivia’s happened far too often. The difference is that today, thanks to modern science, we now have the tools to stop them.

Thanks to safety cautions from the COVID-19 pandemic, a strain of influenza has been completely eliminated.

If you were one of the millions who masked up, washed your hands thoroughly and socially distanced, pat yourself on the back—you may have helped change the course of human history.

Scientists say that thanks to these safety precautions, which were introduced in early 2020 as a way to stop transmission of the novel COVID-19 virus, a strain of influenza has been completely eliminated. This marks the first time in human history that a virus has been wiped out through non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as vaccines.

The flu shot, explained

Influenza viruses type A and B are responsible for the majority of human illnesses and the flu season.

Centers for Disease Control

For more than a decade, flu shots have protected against two types of the influenza virus–type A and type B. While there are four different strains of influenza in existence (A, B, C, and D), only strains A, B, and C are capable of infecting humans, and only A and B cause pandemics. In other words, if you catch the flu during flu season, you’re most likely sick with flu type A or B.

Flu vaccines contain inactivated—or dead—influenza virus. These inactivated viruses can’t cause sickness in humans, but when administered as part of a vaccine, they teach a person’s immune system to recognize and kill those viruses when they’re encountered in the wild.

Each spring, a panel of experts gives a recommendation to the US Food and Drug Administration on which strains of each flu type to include in that year’s flu vaccine, depending on what surveillance data says is circulating and what they believe is likely to cause the most illness during the upcoming flu season. For the past decade, Americans have had access to vaccines that provide protection against two strains of influenza A and two lineages of influenza B, known as the Victoria lineage and the Yamagata lineage. But this year, the seasonal flu shot won’t include the Yamagata strain, because the Yamagata strain is no longer circulating among humans.

How Yamagata Disappeared

Flu surveillance data from the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) shows that the Yamagata lineage of flu type B has not been sequenced since April 2020.

Nature

Experts believe that the Yamagata lineage had already been in decline before the pandemic hit, likely because the strain was naturally less capable of infecting large numbers of people compared to the other strains. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the resulting safety precautions such as social distancing, isolating, hand-washing, and masking were enough to drive the virus into extinction completely.

Because the strain hasn’t been circulating since 2020, the FDA elected to remove the Yamagata strain from the seasonal flu vaccine. This will mark the first time since 2012 that the annual flu shot will be trivalent (three-component) rather than quadrivalent (four-component).

Should I still get the flu shot?

The flu shot will protect against fewer strains this year—but that doesn’t mean we should skip it. Influenza places a substantial health burden on the United States every year, responsible for hundreds of thousands of hospitalizations and tens of thousands of deaths. The flu shot has been shown to prevent millions of illnesses each year (more than six million during the 2022-2023 season). And while it’s still possible to catch the flu after getting the flu shot, studies show that people are far less likely to be hospitalized or die when they’re vaccinated.

Another unexpected benefit of dropping the Yamagata strain from the seasonal vaccine? This will possibly make production of the flu vaccine faster, and enable manufacturers to make more vaccines, helping countries who have a flu vaccine shortage and potentially saving millions more lives.

After his grandmother’s dementia diagnosis, one man invented a snack to keep her healthy and hydrated.

Founder Lewis Hornby and his grandmother Pat, sampling Jelly Drops—an edible gummy containing water and life-saving electrolytes.

On a visit to his grandmother’s nursing home in 2016, college student Lewis Hornby made a shocking discovery: Dehydration is a common (and dangerous) problem among seniors—especially those that are diagnosed with dementia.

Hornby’s grandmother, Pat, had always had difficulty keeping up her water intake as she got older, a common issue with seniors. As we age, our body composition changes, and we naturally hold less water than younger adults or children, so it’s easier to become dehydrated quickly if those fluids aren’t replenished. What’s more, our thirst signals diminish naturally as we age as well—meaning our body is not as good as it once was in letting us know that we need to rehydrate. This often creates a perfect storm that commonly leads to dehydration. In Pat’s case, her dehydration was so severe she nearly died.

When Lewis Hornby visited his grandmother at her nursing home afterward, he learned that dehydration especially affects people with dementia, as they often don’t feel thirst cues at all, or may not recognize how to use cups correctly. But while dementia patients often don’t remember to drink water, it seemed to Hornby that they had less problem remembering to eat, particularly candy.

Hornby wanted to create a solution for elderly people who struggled keeping their fluid intake up. He spent the next eighteen months researching and designing a solution and securing funding for his project. In 2019, Hornby won a sizable grant from the Alzheimer’s Society, a UK-based care and research charity for people with dementia and their caregivers. Together, through the charity’s Accelerator Program, they created a bite-sized, sugar-free, edible jelly drop that looked and tasted like candy. The candy, called Jelly Drops, contained 95% water and electrolytes—important minerals that are often lost during dehydration. The final product launched in 2020—and was an immediate success. The drops were able to provide extra hydration to the elderly, as well as help keep dementia patients safe, since dehydration commonly leads to confusion, hospitalization, and sometimes even death.

Not only did Jelly Drops quickly become a favorite snack among dementia patients in the UK, but they were able to provide an additional boost of hydration to hospital workers during the pandemic. In NHS coronavirus hospital wards, patients infected with the virus were regularly given Jelly Drops to keep their fluid levels normal—and staff members snacked on them as well, since long shifts and personal protective equipment (PPE) they were required to wear often left them feeling parched.

In April 2022, Jelly Drops launched in the United States. The company continues to donate 1% of its profits to help fund Alzheimer’s research.