Paralyzed By Polio, This British Tea Broker Changed the Course Of Medical History Forever

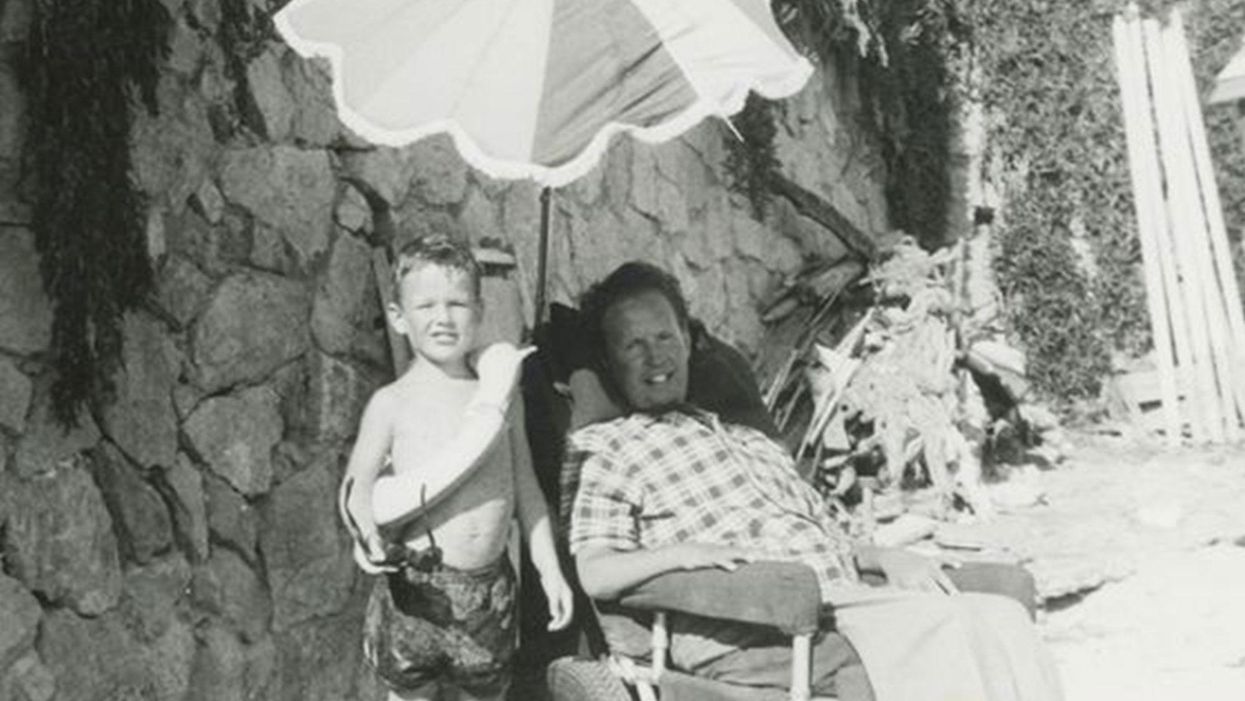

Robin Cavendish in his special wheelchair with his son Jonathan in the 1960s.

In December 1958, on a vacation with his wife in Kenya, a 28-year-old British tea broker named Robin Cavendish became suddenly ill. Neither he nor his wife Diana knew it at the time, but Robin's illness would change the course of medical history forever.

Robin was rushed to a nearby hospital in Kenya where the medical staff delivered the crushing news: Robin had contracted polio, and the paralysis creeping up his body was almost certainly permanent. The doctors placed Robin on a ventilator through a tracheotomy in his neck, as the paralysis from his polio infection had rendered him unable to breathe on his own – and going off the average life expectancy at the time, they gave him only three months to live. Robin and Diana (who was pregnant at the time with their first child, Jonathan) flew back to England so he could be admitted to a hospital. They mentally prepared to wait out Robin's final days.

But Robin did something unexpected when he returned to the UK – just one of many things that would astonish doctors over the next several years: He survived. Diana gave birth to Jonathan in February 1959 and continued to visit Robin regularly in the hospital with the baby. Despite doctors warning that he would soon succumb to his illness, Robin kept living.

After a year in the hospital, Diana suggested something radical: She wanted Robin to leave the hospital and live at home in South Oxfordshire for as long as he possibly could, with her as his nurse. At the time, this suggestion was unheard of. People like Robin who depended on machinery to keep them breathing had only ever lived inside hospital walls, as the prevailing belief was that the machinery needed to keep them alive was too complicated for laypeople to operate. But Diana and Robin were up for the challenges – and the risks. Because his ventilator ran on electricity, if the house were to unexpectedly lose power, Diana would either need to restore power quickly or hand-pump air into his lungs to keep him alive.

Robin's wheelchair was not only the first of its kind; it became the model for the respiratory wheelchairs that people still use today.

In an interview as an adult, Jonathan Cavendish reflected on his parents' decision to live outside the hospital on a ventilator: "My father's mantra was quality of life," he explained. "He could have stayed in the hospital, but he didn't think that was as good of a life as he could manage. He would rather be two minutes away from death and living a full life."

After a few years of living at home, however, Robin became tired of being confined to his bed. He longed to sit outside, to visit friends, to travel – but had no way of doing so without his ventilator. So together with his friend Teddy Hall, a professor and engineer at Oxford University, the two collaborated in 1962 to create an entirely new invention: a battery-operated wheelchair prototype with a ventilator built in. With this, Robin could now venture outside the house – and soon the Cavendish family became famous for taking vacations. It was something that, by all accounts, had never been done before by someone who was ventilator-dependent. Robin and Hall also designed a van so that the wheelchair could be plugged in and powered during travel. Jonathan Cavendish later recalled a particular family vacation that nearly ended in disaster when the van broke down outside of Barcelona, Spain:

"My poor old uncle [plugged] my father's chair into the wrong socket," Cavendish later recalled, causing the electricity to short. "There was fire and smoke, and both the van and the chair ground to a halt." Johnathan, who was eight or nine at the time, his mother, and his uncle took turns hand-pumping Robin's ventilator by the roadside for the next thirty-six hours, waiting for Professor Hall to arrive in town and repair the van. Rather than being panicked, the Cavendishes managed to turn the vigil into a party. Townspeople came to greet them, bringing food and music, and a local priest even stopped by to give his blessing.

Robin had become a pioneer, showing the world that a person with severe disabilities could still have mobility, access, and a fuller quality of life than anyone had imagined. His mission, along with Hall's, then became gifting this independence to others like himself. Robin and Hall raised money – first from the Ernest Kleinwort Charitable Trust, and then from the British Department of Health – to fund more ventilator chairs, which were then manufactured by Hall's company, Littlemore Scientific Engineering, and given to fellow patients who wanted to live full lives at home. Robin and Hall used themselves as guinea pigs, testing out different models of the chairs and collaborating with scientists to create other devices for those with disabilities. One invention, called the Possum, allowed paraplegics to control things like the telephone and television set with just a nod of the head. Robin's wheelchair was not only the first of its kind; it became the model for the respiratory wheelchairs that people still use today.

Robin went on to enjoy a long and happy life with his family at their house in South Oxfordshire, surrounded by friends who would later attest to his "down-to-earth" personality, his sense of humor, and his "irresistible" charm. When he died peacefully at his home in 1994 at age 64, he was considered the world's oldest-living person who used a ventilator outside the hospital – breaking yet another barrier for what medical science thought was possible.

How Excessive Regulation Helped Ignite COVID-19's Rampant Spread

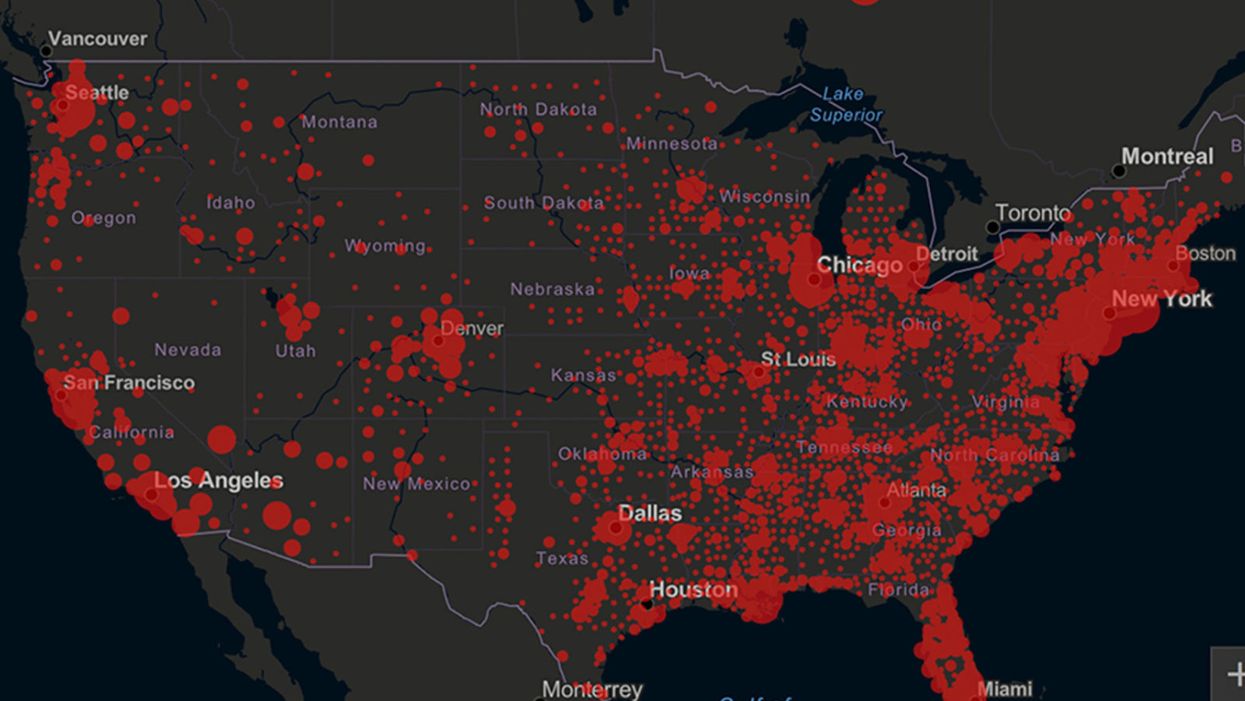

Screenshot of an interactive map of coronavirus cases across the United States, current as of 1:45 p.m. Pacific time on Tuesday, March 31st. Full map accessible at https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

When historians of the future look back at the 2020 pandemic, the heroic work of Helen Y. Chu, a flu researcher at the University of Washington, will be worthy of recognition.

Chu's team bravely defied the order and conducted the testing anyway.

In late January, Chu was testing nasal swabs for the Seattle Flu Study to monitor influenza spread when she learned of the first case of COVID-19 in Washington state. She deemed it a pressing public health matter to document if and how the illness was spreading locally, so that early containment efforts could succeed. So she sought regulatory approval to adapt the Flu Study to test for the coronavirus, but the federal government denied the request because the original project was funded to study only influenza.

Aware of the urgency, Chu's team bravely defied the order and conducted the testing anyway. Soon they identified a local case in a teenager without any travel history, followed by others. Still, the government tried to shutter their efforts until the outbreak grew dangerous enough to command attention.

Needless testing delays, prompted by excessive regulatory interference, eliminated any chances of curbing the pandemic at its initial stages. Even after Chu went out on a limb to sound alarms, a heavy-handed bureaucracy crushed the nation's ability to roll out early and widespread testing across the country. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention infamously blundered its own test, while also impeding state and private labs from coming on board, fueling a massive shortage.

The long holdup created "a backlog of testing that needed to be done," says Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease specialist who is a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security.

In a public health crisis, "the ideal situation" would allow the government's test to be "supplanted by private laboratories" without such "a lag in that transition," Adalja says. Only after the eventual release of CDC's test could private industry "begin in earnest" to develop its own versions under the Food and Drug Administration's emergency use authorization.

In a statement, CDC acknowledged that "this process has not gone as smoothly as we would have liked, but there is currently no backlog for testing at CDC."

Now, universities and corporations are in a race against time, playing catch up as the virus continues its relentless spread, also afflicting many health care workers on the front lines.

"Home-testing accessibility is key to preventing further spread of the COVID-19 pandemic."

Hospitals are attempting to add the novel coronavirus to the testing panel of their existent diagnostic machines, which would reduce the results processing time from 48 hours to as little as four hours. Meanwhile, at least four companies announced plans to deliver at-home collection tests to help meet the demand – before a startling injunction by the FDA halted their plans.

Everlywell, an Austin, Texas-based digital health company, had been set to launch online sales of at-home collection kits directly to consumers last week. Scaling up in a matter of days to an initial supply of 30,000 tests, Everlywell collaborated with multiple laboratories where consumers could ship their nasal swab samples overnight, projecting capacity to screen a quarter-million individuals on a weekly basis, says Frank Ong, chief medical and scientific officer.

Secure digital results would have been available online within 48 hours of a sample's arrival at the lab, as well as a telehealth consultation with an independent, board-certified doctor if someone tested positive, for an inclusive $135 cost. The test has a less than 3 percent false-negative rate, Ong says, and in the event of an inadequate self-swab, the lab would not report a conclusive finding. "Home-testing accessibility," he says, "is key to preventing further spread of the COVID-19 pandemic."

But on March 20, the FDA announced restrictions on home collection tests due to concerns about accuracy. The agency did note "the public health value in expanding the availability of COVID-19 testing through safe and accurate tests that may include home collection," while adding that "we are actively working with test developers in this space."

After the restrictions were announced, Everlywell decided to allocate its initial supply of COVID-19 collection kits to hospitals, clinics, nursing homes, and other qualifying health care companies that can commit to no-cost screening of frontline workers and high-risk symptomatic patients. For now, no consumers can order a home-collection test.

"Losing two months is close to disastrous, and that's what we did."

Currently, the U.S. has ramped up to testing an estimated 100,000 people a day, according to Stat News. But 150,000 or more Americans should be tested every day, says Ashish Jha, professor and director of the Harvard Global Health Institute. Due to the dearth of tests, many sick people who suspect they are infected still cannot get confirmation unless they need to be hospitalized.

To give a concrete sense of how far behind we are in testing, consider Palm Beach County, Fla. The state's only drive-thru test center just opened there, requiring an appointment. The center aims to test 750 people per day, but more than 330,000 people have already called to try to book a slot.

"This is such a rapidly moving infection that losing a few days is bad, and losing a couple of weeks is terrible," says Jha, a practicing general internist. "Losing two months is close to disastrous, and that's what we did."

At this point, it will take a long time to fully ramp up. "We are blindfolded," he adds, "and I'd like to take the blindfolds off so we can fight this battle with our eyes wide open."

Better late than never: Yesterday, FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn said in a statement that the agency has worked with more than 230 test developers and has approved 20 tests since January. An especially notable one was authorized last Friday – 67 days since the country's first known case in Washington state. It's a rapid point-of-care test from medical-device firm Abbott that provides positive results in five minutes and negative results in 13 minutes. Abbott will send 50,000 tests a day to urgent care settings. The first tests are expected to ship tomorrow.

Your Privacy vs. the Public's Health: High-Tech Tracking to Fight COVID-19 Evokes Orwell

Governments around the world are using technology to track their citizens to contain COVID-19.

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed public health and personal privacy on a collision course, as smartphone technology has completely rewritten the book on contact tracing.

It's not surprising that an autocratic regime like China would adopt such measures, but democracies such as Israel have taken a similar path.

The gold standard – patient interviews and detective work – had been in place for more than a century. It's been all but replaced by GPS data in smartphones, which allows contact tracing to occur not only virtually in real time, but with vastly more precision.

China has gone the furthest in using such tech to monitor and prevent the spread of the coronavirus. It developed an app called Health Code to determine which of its citizens are infected or at risk of becoming infected. It has assigned each individual a color code – red, yellow or green – and restricts their movement depending on their assignment. It has also leveraged its millions of public video cameras in conjunction with facial recognition tech to identify people in public who are not wearing masks.

It's not surprising that an autocratic regime like China would adopt such measures, but democracies such as Israel have taken a similar path. The national security agency Shin Bet this week began analyzing all personal cellphone data under emergency measures approved by the government. It texts individuals when it's determined they had been in contact with someone who had the coronavirus. In Spain and China, police have sent drones aloft searching for people violating stay-at-home orders. Commands to disperse can be issued through audio systems built into the aircraft. In the U.S., efforts are underway to lift federal restrictions on drones so that police can use them to prevent people from gathering.

The chief executive of a drone manufacturer in the U.S. aptly summed up the situation in an interview with the Financial Times: "It seems a little Orwellian, but this could save lives."

Epidemics and how they're surveilled often pose thorny dilemmas, according to Craig Klugman, a bioethicist and professor of health sciences at DePaul University in Chicago. "There's always a moral issue to contact tracing," he said, adding that the issue doesn't change by nation, only in the way it's resolved.

"Once certain privacy barriers have been breached, it can be difficult to roll them back again."

In China, there's little to no expectation for privacy, so their decision to take the most extreme measures makes sense to Klugman. "In China, the community comes first. In the U.S., individual rights come first," he said.

As the U.S. has scrambled to develop testing kits and manufacture ventilators to identify potential patients and treat them, individual rights have mostly not received any scrutiny. However, that could change in the coming weeks.

The American approach is also leaning toward using smartphone apps, but in a way that may preserve the privacy of users. Researchers at MIT have released a prototype known as Private Kit: Safe Paths. Patients diagnosed with the coronavirus can use the app to disclose their location trail for the prior 28 days to other users without releasing their specific identity. They also have the option of sharing the data with public health officials. But such an app would only be effective if there is a significant number of users.

Singapore is offering a similar app to its citizens known as TraceTogether, which uses both GPS and Bluetooth pings among users to trace potential encounters. It's being offered on a voluntary basis.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation, the leading nonprofit organization defending civil liberties in the digital world, said it is monitoring how these apps are developed and deployed. "Governments around the world are demanding new dragnet location surveillance powers to contain the COVID-19 outbreak," it said in a statement. "But before the public allows their governments to implement such systems, governments must explain to the public how these systems would be effective in stopping the spread of COVID-19. There's no questioning the need for far-reaching public health measures to meet this urgent challenge, but those measures must be scientifically rigorous, and based on the expertise of public health professionals."

Andrew Geronimo, director of the intellectual property venture clinic at the Case Western University School of Law, said that the U.S. government is currently in talks with Facebook, Google and other tech companies about using deidentified location data from smartphones to better monitor the progress of the outbreak. He was hesitant to endorse such a step.

"These companies may say that all of this data is anonymized," he said, "but studies have shown that it is difficult to fully anonymize data sets that contain so much information about us."

Beyond the technical issues, social attitudes may mount another challenge. Epic events such as 9/11 tend to loosen vigilance toward protecting privacy, according to Klugman and Geronimo. And as more people are sickened and hospitalized in the U.S. with COVID-19, Klugman believes more Americans will be willing to allow themselves to be tracked. "If that happens, there needs to be a time limitation," he said.

However, even if time limits are put in place, Geronimo believes it would lead to an even greater rollback of privacy during the next crisis.

"Once certain privacy barriers have been breached, it can be difficult to roll them back again," he warned. "And the prior incidents could always be used as a precedent – or as proof of concept."