Paralyzed By Polio, This British Tea Broker Changed the Course Of Medical History Forever

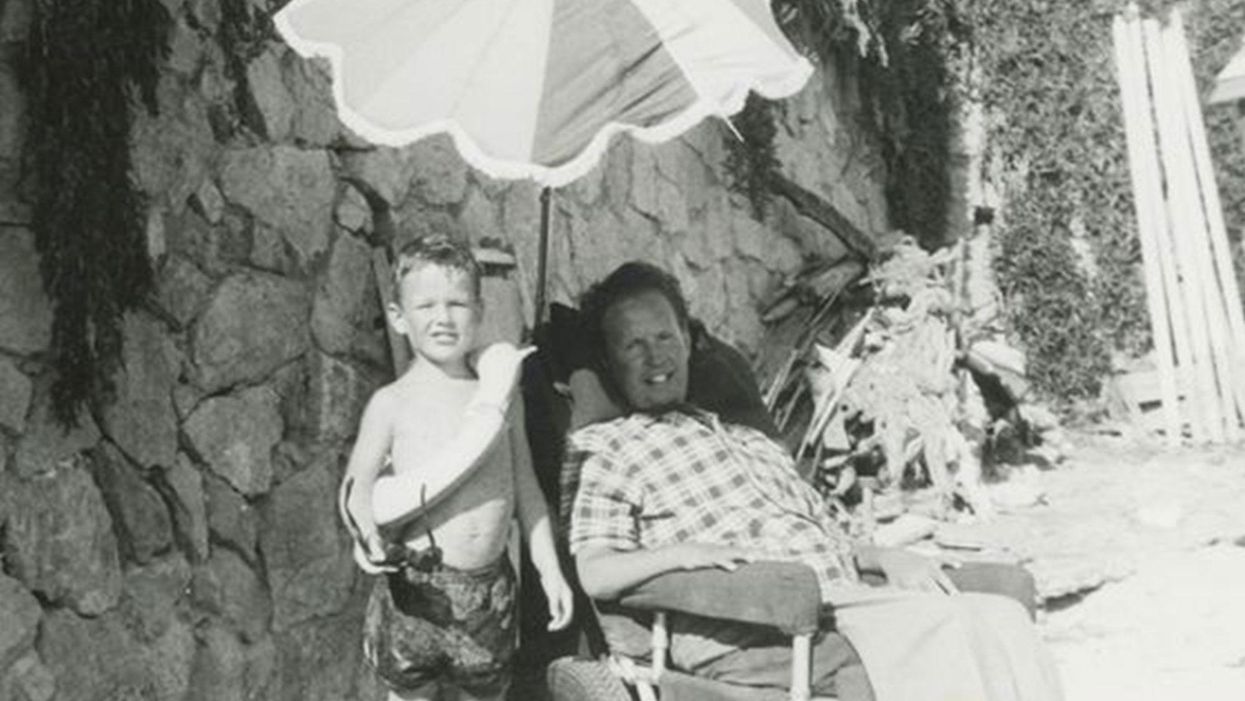

Robin Cavendish in his special wheelchair with his son Jonathan in the 1960s.

In December 1958, on a vacation with his wife in Kenya, a 28-year-old British tea broker named Robin Cavendish became suddenly ill. Neither he nor his wife Diana knew it at the time, but Robin's illness would change the course of medical history forever.

Robin was rushed to a nearby hospital in Kenya where the medical staff delivered the crushing news: Robin had contracted polio, and the paralysis creeping up his body was almost certainly permanent. The doctors placed Robin on a ventilator through a tracheotomy in his neck, as the paralysis from his polio infection had rendered him unable to breathe on his own – and going off the average life expectancy at the time, they gave him only three months to live. Robin and Diana (who was pregnant at the time with their first child, Jonathan) flew back to England so he could be admitted to a hospital. They mentally prepared to wait out Robin's final days.

But Robin did something unexpected when he returned to the UK – just one of many things that would astonish doctors over the next several years: He survived. Diana gave birth to Jonathan in February 1959 and continued to visit Robin regularly in the hospital with the baby. Despite doctors warning that he would soon succumb to his illness, Robin kept living.

After a year in the hospital, Diana suggested something radical: She wanted Robin to leave the hospital and live at home in South Oxfordshire for as long as he possibly could, with her as his nurse. At the time, this suggestion was unheard of. People like Robin who depended on machinery to keep them breathing had only ever lived inside hospital walls, as the prevailing belief was that the machinery needed to keep them alive was too complicated for laypeople to operate. But Diana and Robin were up for the challenges – and the risks. Because his ventilator ran on electricity, if the house were to unexpectedly lose power, Diana would either need to restore power quickly or hand-pump air into his lungs to keep him alive.

Robin's wheelchair was not only the first of its kind; it became the model for the respiratory wheelchairs that people still use today.

In an interview as an adult, Jonathan Cavendish reflected on his parents' decision to live outside the hospital on a ventilator: "My father's mantra was quality of life," he explained. "He could have stayed in the hospital, but he didn't think that was as good of a life as he could manage. He would rather be two minutes away from death and living a full life."

After a few years of living at home, however, Robin became tired of being confined to his bed. He longed to sit outside, to visit friends, to travel – but had no way of doing so without his ventilator. So together with his friend Teddy Hall, a professor and engineer at Oxford University, the two collaborated in 1962 to create an entirely new invention: a battery-operated wheelchair prototype with a ventilator built in. With this, Robin could now venture outside the house – and soon the Cavendish family became famous for taking vacations. It was something that, by all accounts, had never been done before by someone who was ventilator-dependent. Robin and Hall also designed a van so that the wheelchair could be plugged in and powered during travel. Jonathan Cavendish later recalled a particular family vacation that nearly ended in disaster when the van broke down outside of Barcelona, Spain:

"My poor old uncle [plugged] my father's chair into the wrong socket," Cavendish later recalled, causing the electricity to short. "There was fire and smoke, and both the van and the chair ground to a halt." Johnathan, who was eight or nine at the time, his mother, and his uncle took turns hand-pumping Robin's ventilator by the roadside for the next thirty-six hours, waiting for Professor Hall to arrive in town and repair the van. Rather than being panicked, the Cavendishes managed to turn the vigil into a party. Townspeople came to greet them, bringing food and music, and a local priest even stopped by to give his blessing.

Robin had become a pioneer, showing the world that a person with severe disabilities could still have mobility, access, and a fuller quality of life than anyone had imagined. His mission, along with Hall's, then became gifting this independence to others like himself. Robin and Hall raised money – first from the Ernest Kleinwort Charitable Trust, and then from the British Department of Health – to fund more ventilator chairs, which were then manufactured by Hall's company, Littlemore Scientific Engineering, and given to fellow patients who wanted to live full lives at home. Robin and Hall used themselves as guinea pigs, testing out different models of the chairs and collaborating with scientists to create other devices for those with disabilities. One invention, called the Possum, allowed paraplegics to control things like the telephone and television set with just a nod of the head. Robin's wheelchair was not only the first of its kind; it became the model for the respiratory wheelchairs that people still use today.

Robin went on to enjoy a long and happy life with his family at their house in South Oxfordshire, surrounded by friends who would later attest to his "down-to-earth" personality, his sense of humor, and his "irresistible" charm. When he died peacefully at his home in 1994 at age 64, he was considered the world's oldest-living person who used a ventilator outside the hospital – breaking yet another barrier for what medical science thought was possible.

More Families Are Using Nanny Cams to Watch Elderly Loved Ones, Raising Ethical Questions

Jackie Costanzo and her 93-year-old mom, Louise, are happy to have an extra way to stay connected with the camera, which is normally placed on a television stand facing her mom's bed.

After Jackie Costanzo's mother broke her right hip in a fall, she needed more hands-on care in her assisted-living apartment near Sacramento, California. A social worker from her health plan suggested installing a video camera to help ensure those services were provided.

Without the camera, Costanzo wouldn't have a way to confirm that caregivers had followed through with serving meals, changing clothes, and fulfilling other care needs.

When Costanzo placed the device in May 2018, she informed the administrator and staff, and at first, there were no objections. The facility posted a sign on the apartment's front door, alerting anyone who entered of recording in progress.

But this past spring, a new management company came across the sign and threatened to issue a 30-day eviction notice to her 93-year-old mother, Louise Munch, who has dementia, for violating a policy that prohibits cameras in residents' rooms. With encouragement from California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform, Costanzo researched the state's regulations but couldn't find anything to support or deny camera use. She refused to remove the recording device and prevailed.

"In essence, my mom was 'grandfathered in' because she moved in under a management company that did not specify that residents could not have cameras," says Costanzo, 73, a retired elementary schoolteacher who lives a three-hour drive away, in Silicon Valley, and visits one day every two weeks. Without the camera, Costanzo, who is her mother's only surviving child, wouldn't have a way to confirm that caregivers had followed through with serving meals, changing clothes, and fulfilling other care needs.

As technological innovations enable next of kin to remain apprised of the elderly's daily care in long-term care facilities, surveillance cameras bring legal and privacy issues to the forefront of a complex ethical debate. Families place them overtly or covertly—disguised in a makeshift clock radio, for instance—when they suspect or fear abuse or neglect, so they can maintain a watchful eye, perhaps deterring egregious behavior. But the cameras also capture intimate caregiving tasks, such as bathing and toileting, as well as dressing and undressing, which may undermine the dignity of residents.

So far, laws or guidelines in eight states—Illinois, Maryland, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and Washington—have granted families the rights to install cameras in a resident's room. In addition, about 15 other states have proposed legislation. Some states, such as Pennsylvania, have put forth regulatory compliance guidance, according to a column published in the July/August 2018 issue of Annals of Long-Term Care.

The increasing prevalence of this legislation has placed it on the radar of long-term care providers. It also suggests a trend to clarify responsible camera use in monitoring services while respecting privacy, says Victor Lane Rose, the column's editor and director of aging services at ECRI Institute, a health care nonprofit near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

In most cases, a resident's family installs a camera or instigates a request in hopes of sparing their loved one from the harms of abuse, says James Wright, a family physician who serves as the ethics committee's vice chair of the Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine in Columbia, Maryland. A camera also allows the family to check in on the resident from afar and remain on alert for a potential fall or agitated state, he says.

"It's rare that a facility will have 24-hour presence in a patient's room. You won't have a nurse in there all the time," says Wright, who is also medical director of two long-term care centers and one assisted-living facility around Richmond, Virginia. Particularly "with dementia, the family often wonders" if their loved one is safe.

While offering families peace of mind, he notes that video cameras can also help exonerate caregivers accused of abuse or theft. Hearing aids, which typically cost between $2,000 and $3,000 each, often go missing. By reviewing a video together, families and administrators may find clues to a device's disappearance. Conversely, Wright empathizes with the main counterargument against camera use, which is the belief that "invasion of privacy is also invasion of human dignity."

In respecting modesty, ethical questions abound over whether a camera should be turned off when a patient is in the midst of receiving personal care, such as dressing and undressing or using bedpans. Other ethical issues revolve around who may access the recordings, says Lori Smetanka, executive director of the National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care in Washington, D.C.

Video cameras, she contends, are only one tool in shielding residents from abuse. They are "not substitutes for personal involvement," she says. "People need to be very vigilant visiting their family members, and facilities have a responsibility to ensure that residents are free of abuse."

Lack of accountability perpetuates abuse in long-term care settings and stems in large part from systemic underfunding.

Educating employees in abuse prevention becomes paramount, and families should ask about staff training before placing their loved one in a long-term care facility, Smetanka says. Prior to installing a camera, she recommends consulting an attorney who is familiar with this issue.

But thoughts of a camera often don't occur to families until an adverse event affects their loved one, says Toby Edelman, a senior policy attorney at the Center for Medicare Advocacy, a nonprofit organization with headquarters in Washington, D.C., and Connecticut.

"These cameras can show exactly what's going on," she explains, noting that prosecutors have used the recordings in litigation. "When residents have injuries of unknown origin" and they can't verbalize what happened to them, "the cameras may document that yes, the resident was actually hit by somebody."

With a resident's safety and security being "the most important consideration," the American Health Care Association in Washington, D.C., which represents long-term and post-acute care providers, supports allowing states, clinicians, and patients to decide about camera use on a local level, says David Gifford, senior vice president of quality and regulatory affairs and chief medical officer.

"We've seen some success with tools such as permissive legislation, where residents and their loved ones have the ability to determine whether a camera is right for them while working with the center openly and ensuring the confidentiality of other residents," says Gifford, who practiced as a geriatrician. "It is important to note, however, that surveillance cameras are still only one element of the quality matrix. We can never hope to truly improve quality care by catching bad actors after the fact."

Lack of accountability perpetuates abuse in long-term care settings and stems in large part from systemic underfunding. Low wages and morale are tied to high turnover, and cameras don't address this overarching problem, says Clara Berridge, an assistant professor of social work at the University of Washington in Seattle, who has co-authored articles on surveillance devices in elder care.

Employees often don't perceive a nursing assistant position as a long-term career trajectory and may not feel vested in the workplace. Training in the recognition and reporting of abuse becomes ineffective when workers quit shortly thereafter. Many must juggle multiple jobs to make ends meet. Staffing shortages are endemic, leading to inadequate oversight of residents and voicing of abuse complaints, she says.

In Berridge's assessment, cameras may do more harm than good. Respondents to a survey she conducted of nursing homes and assisted-living facilities in the United States found that recording devices tend to fuel workers' anxiety amid a culture that further demoralizes and dehumanizes the care they provide.

Consent becomes particularly thorny in shared rooms, which are more common than not in nursing homes. States that permit in-room cameras mandate that roommates or their legal representative be made aware. Even if the camera is directed away from their bed, it will still capture conversations as well as movements that enter its scope. "Surveillance isn't the best way to protect adults in need of support," Berridge says. "Public investment in quality care is."

"The camera is invaluable. But there's no law that says you can have it automatically, so that's wrong."

In the one-bedroom assisted-living apartment where Costanzo's mother lives alone, consent from another resident wasn't needed. Without a roommate, the camera is much less intrusive, although Costanzo wishes she had put one in the living room, not just the bedroom, for more security.

Her safety concerns escalated when she read about a Texas serial killer who smothered victims after gaining access to senior care facilities by "masquerading as a maintenance man." She points to such horrifying incidents, although exceedingly rare, as further justification for permitting cameras to help guard the vulnerable against abuse in long-term care settings. And she hopes to advocate for an applicable law in California.

"The camera is invaluable," says Costanzo, who pays for monthly Wi-Fi service so she can see and interact with her mother, who turns 94 in October, any time of day or night. "But there's no law that says you can have it automatically, so that's wrong."

Scientists Used Fruit Flies to Quickly Develop a Personalized Cancer Treatment for a Dying Man

Genetically engineered fruit flies are being used in early research to screen novel combinations of cancer drugs for individual patients.

Imagine a man with colorectal cancer that has spread throughout his body. His tumor is not responding to traditional chemotherapy. He needs a radically effective treatment as soon as possible and there's no time to wait for a new drug or a new clinical trial.

A plethora of novel combinations of treatments can be screened quickly on as many as 400,000 flies at once.

This was the very real, and terrifying, situation of a recent patient at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City. So his doctors turned to a new tactic to speed up the search for a treatment that would save him: Fruit flies.

Yes, fruit flies. Those annoying little buggers that descend on opened food containers are actually leading scientists to fully personalized cancer treatments. Oncology advances often are more about about utilizing old drugs in new combinations than about adding new drugs. But classically, the development of each new chemotherapy drug combination has required studies involving numerous patients spread over many years or decades.

With the fruit fly method, however, a novel treatment -- in the sense that a particular combination of drugs and the timing of their administration has never been used before -- is developed for each patient, almost like on Star Trek, when, faced suddenly with an unknown disease, a futuristic physician researches it and develops a cure quickly enough to save the patient's life.

How It Works

Using genetic engineering techniques, researchers produce a population of fruit fly embryos, each of which is programmed to develop a replica of the patient's cancer.

Since a lot of genetically identical fly embryos can be created, and since they hatch from eggs within 30 hours and then mature within days, a plethora of novel combinations of treatments can be screened quickly on as many as 400,000 flies at once. Then, only the regimens that are effective are administered to the patient.

Biotech entrepreneur Laura Towart, CEO of the UK- and Ireland-based company, My Personal Therapeutics, is partnering with Mount Sinai to develop and test the fruit fly tactic. The researchers recently published a paper demonstrating that the tumor of the man with metastatic colorectal cancer had shrunk considerably following the treatment, and remained stable for 11 months, although he eventually succumbed to his illness.

Open Questions

Cancer is in fact many different diseases, even if it strikes two people in the same place, and both cancers look the same under a microscope. At the level of DNA, RNA, proteins, and other molecular factors, each cancer is unique – and may require a unique treatment approach.

Determining the true impact on cancer mortality will require clinical trials involving many more patients.

"Anatomy of a cancer still plays a major role, if you're a surgeon or radiation oncologist, but the medical approach to cancer therapy is moving toward treatments that are personalized based on other factors," notes Dr. Howard McLeod, an internationally recognized expert on cancer genetics at the Moffitt Cancer Center, in Tampa, Florida. "We are also headed into an era when even the methods for monitoring patients are individualized."

One big unresolved question about the fruit fly screening approach is how effective it will be in terms of actually extending life. Determining the true impact on cancer mortality will require clinical trials involving many more patients.

Next Up

Using machine learning and artificial intelligence, Towart is now working to build a service called TuMatch that will offer rapid and affordable personalized treatment recommendations for all genetically driven cancers. "We hope to have TuMatch available to patients with colorectal/GI cancers by January 2020," she says. "We are also offering [the fruit fly approach] for patients with rare genetic diseases and for patients who are diabetic."

Are Towart's fruit flies the answer to why the man's tumor shrunk? To be sure, the definitive answer will come from further research that is expected soon, but it's also clear that, prior to the treatment, there was nothing left to do for that particular patient. Thus, although it's early in the game, there's a pretty good rationale for optimism.