Paralyzed By Polio, This British Tea Broker Changed the Course Of Medical History Forever

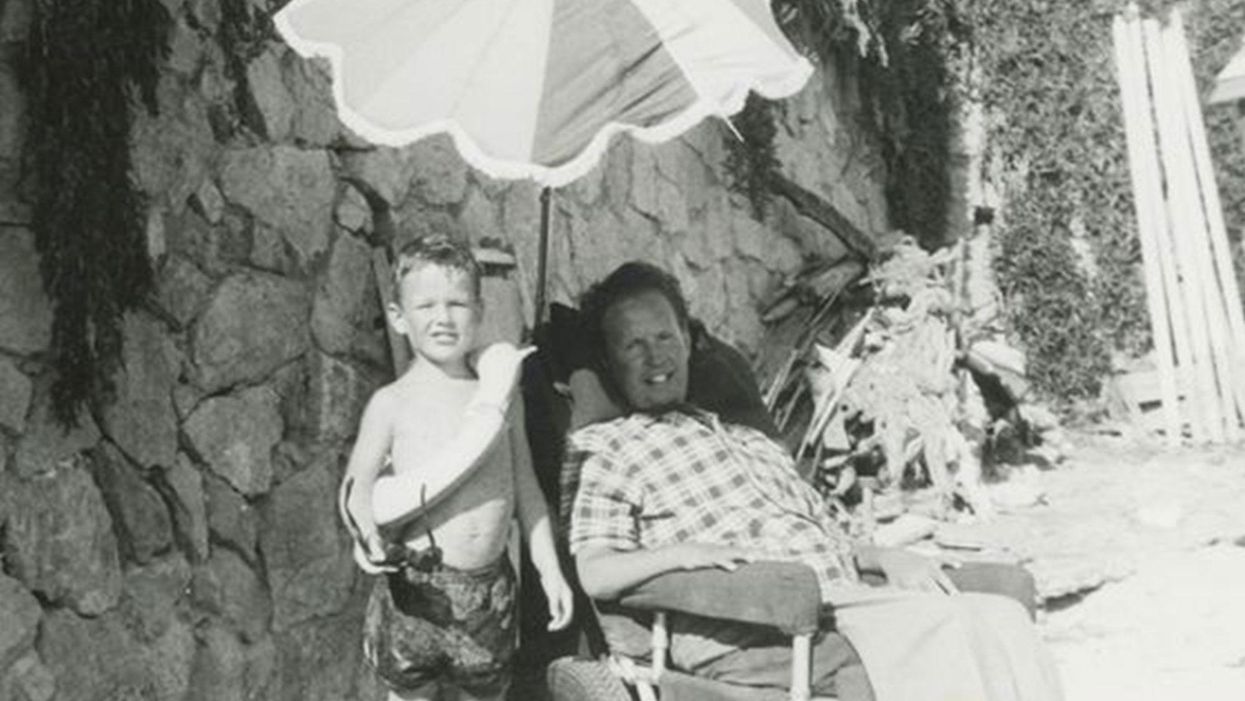

Robin Cavendish in his special wheelchair with his son Jonathan in the 1960s.

In December 1958, on a vacation with his wife in Kenya, a 28-year-old British tea broker named Robin Cavendish became suddenly ill. Neither he nor his wife Diana knew it at the time, but Robin's illness would change the course of medical history forever.

Robin was rushed to a nearby hospital in Kenya where the medical staff delivered the crushing news: Robin had contracted polio, and the paralysis creeping up his body was almost certainly permanent. The doctors placed Robin on a ventilator through a tracheotomy in his neck, as the paralysis from his polio infection had rendered him unable to breathe on his own – and going off the average life expectancy at the time, they gave him only three months to live. Robin and Diana (who was pregnant at the time with their first child, Jonathan) flew back to England so he could be admitted to a hospital. They mentally prepared to wait out Robin's final days.

But Robin did something unexpected when he returned to the UK – just one of many things that would astonish doctors over the next several years: He survived. Diana gave birth to Jonathan in February 1959 and continued to visit Robin regularly in the hospital with the baby. Despite doctors warning that he would soon succumb to his illness, Robin kept living.

After a year in the hospital, Diana suggested something radical: She wanted Robin to leave the hospital and live at home in South Oxfordshire for as long as he possibly could, with her as his nurse. At the time, this suggestion was unheard of. People like Robin who depended on machinery to keep them breathing had only ever lived inside hospital walls, as the prevailing belief was that the machinery needed to keep them alive was too complicated for laypeople to operate. But Diana and Robin were up for the challenges – and the risks. Because his ventilator ran on electricity, if the house were to unexpectedly lose power, Diana would either need to restore power quickly or hand-pump air into his lungs to keep him alive.

Robin's wheelchair was not only the first of its kind; it became the model for the respiratory wheelchairs that people still use today.

In an interview as an adult, Jonathan Cavendish reflected on his parents' decision to live outside the hospital on a ventilator: "My father's mantra was quality of life," he explained. "He could have stayed in the hospital, but he didn't think that was as good of a life as he could manage. He would rather be two minutes away from death and living a full life."

After a few years of living at home, however, Robin became tired of being confined to his bed. He longed to sit outside, to visit friends, to travel – but had no way of doing so without his ventilator. So together with his friend Teddy Hall, a professor and engineer at Oxford University, the two collaborated in 1962 to create an entirely new invention: a battery-operated wheelchair prototype with a ventilator built in. With this, Robin could now venture outside the house – and soon the Cavendish family became famous for taking vacations. It was something that, by all accounts, had never been done before by someone who was ventilator-dependent. Robin and Hall also designed a van so that the wheelchair could be plugged in and powered during travel. Jonathan Cavendish later recalled a particular family vacation that nearly ended in disaster when the van broke down outside of Barcelona, Spain:

"My poor old uncle [plugged] my father's chair into the wrong socket," Cavendish later recalled, causing the electricity to short. "There was fire and smoke, and both the van and the chair ground to a halt." Johnathan, who was eight or nine at the time, his mother, and his uncle took turns hand-pumping Robin's ventilator by the roadside for the next thirty-six hours, waiting for Professor Hall to arrive in town and repair the van. Rather than being panicked, the Cavendishes managed to turn the vigil into a party. Townspeople came to greet them, bringing food and music, and a local priest even stopped by to give his blessing.

Robin had become a pioneer, showing the world that a person with severe disabilities could still have mobility, access, and a fuller quality of life than anyone had imagined. His mission, along with Hall's, then became gifting this independence to others like himself. Robin and Hall raised money – first from the Ernest Kleinwort Charitable Trust, and then from the British Department of Health – to fund more ventilator chairs, which were then manufactured by Hall's company, Littlemore Scientific Engineering, and given to fellow patients who wanted to live full lives at home. Robin and Hall used themselves as guinea pigs, testing out different models of the chairs and collaborating with scientists to create other devices for those with disabilities. One invention, called the Possum, allowed paraplegics to control things like the telephone and television set with just a nod of the head. Robin's wheelchair was not only the first of its kind; it became the model for the respiratory wheelchairs that people still use today.

Robin went on to enjoy a long and happy life with his family at their house in South Oxfordshire, surrounded by friends who would later attest to his "down-to-earth" personality, his sense of humor, and his "irresistible" charm. When he died peacefully at his home in 1994 at age 64, he was considered the world's oldest-living person who used a ventilator outside the hospital – breaking yet another barrier for what medical science thought was possible.

Elizabeth Holmes Through the Director’s Lens

Elizabeth Holmes.

"The Inventor," a chronicle of Theranos's storied downfall, premiered recently on HBO. Leapsmag reached out to director Alex Gibney, whom The New York Times has called "one of America's most successful and prolific documentary filmmakers," for his perspective on Elizabeth Holmes and the world she inhabited.

Do you think Elizabeth Holmes was a charismatic sociopath from the start — or is she someone who had good intentions, over-promised, and began the lies to keep her business afloat, a "fake it till you make it" entrepreneur like Thomas Edison?

I'm not qualified to say if EH was or is a sociopath. I don't think she started Theranos as a scam whose only purpose was to make money. If she had done so, she surely would have taken more money for herself along the way. I do think that she had good intentions and that she, as you say, "began the lies to keep her business afloat." ([Reporter John] Carreyrou's book points out that those lies began early.) I think that the Edison comparison is instructive for a lot of reasons.

First, Edison was the original "fake-it-till-you-make-it" entrepreneur. That puts this kind of behavior in the mainstream of American business. By saying that, I am NOT endorsing the ethic, just the opposite. As one Enron executive mused about the mendacity there, "Was it fraud or was it bad marketing?" That gives you a sense of how baked-in the "fake it" sensibility is.

"Having a thirst for fame and a noble cause enabled her to think it was OK to lie in service of those goals."

I think EH shares one other thing with Edison, which is a huge ego coupled with a talent for storytelling as long as she is the heroic, larger-than-life main character. It's interesting that EH calls her initial device "Edison." Edison was the world's most famous "inventor," both because of the devices that came out of his shop and and for his ability for "self-invention." As Randall Stross notes in "The Wizard of Menlo Park," he was the first celebrity businessman. In addition to her "good intentions," EH was certainly motivated by fame and glory and many of her lies were in service to those goals.

Having a thirst for fame and a noble cause enabled her to think it was OK to lie in service of those goals. That doesn't excuse the lies. But those noble goals may have allowed EH to excuse them for herself or, more perniciously, to make believe that they weren't lies at all. This is where we get into scary psychological territory.

But rather than thinking of it as freakish, I think it's more productive to think of it as an exaggeration of the way we all lie to others and to ourselves. That's the point of including the Dan Ariely experiment with the dice. In that experiment, most of the subjects cheated more when they thought they were doing it for a good cause. Even more disturbing, that "good cause" allowed them to lie much more effectively because they had come to believe they weren't doing anything wrong. As it turns out, economics isn't a rational practice; it's the practice of rationalizing.

Where EH and Edison differ is that Edison had a firm grip on reality. He knew he could find a way to make the incandescent lightbulb work. There is no evidence that EH was close to making her "Edison" work. But rather than face reality (and possibly adjust her goals) she pretended that her dream was real. That kind of "over-promising" or "bold vision" is one thing when you are making a prototype in the lab. It's a far more serious matter when you are using a deeply flawed system on real patients. EH can tell herself that she had to do that (Walgreens was ready to walk away if she hadn't "gone live") or else Theranos would have run out of money.

But look at the calculation she made: she thought it was worth putting lives at risk in order to make her dream come true. Now we're getting into the realm of the sociopath. But my experience leads me to believe that -- as in the case of the Milgram experiment -- most people don't do terrible things right away, they come to crimes gradually as they become more comfortable with bigger and bigger rationalizations. At Theranos, the more valuable the company became, the bigger grew the lies.

The two whistleblowers come across as courageous heroes, going up against the powerful and intimidating company. The contrast between their youth and lack of power and the old elite backers of Theronos is staggering, and yet justice triumphed. Were the whistleblowers hesitant or afraid to appear in the film, or were they eager to share their stories?

By the time I got to them, they were willing and eager to tell their stories, once I convinced them that I would honor their testimony. In the case of Erika and Tyler, they were nudged to participate by John Carreyrou, in whom they had enormous trust.

"It's simply crazy that no one demanded to see an objective demonstration of the magic box."

Why do you think so many elite veterans of politics and venture capitalism succumbed to Holmes' narrative in the first place, without checking into the details of its technology or financials?

The reasons are all in the film. First, Channing Robertson and many of the old men on her board were clearly charmed by her and maybe attracted to her. They may have rationalized their attraction by convincing themselves it was for a good cause! Second, as Dan Ariely tells us, we all respond to stories -- more than graphs and data -- because they stir us emotionally. EH was a great storyteller. Third, the story of her as a female inventor and entrepreneur in male-dominated Silicon Valley is a tale that they wanted to invest in.

There may have been other factors. EH was very clever about the way she put together an ensemble of credibility. How could Channing Robertson, George Shultz, Henry Kissinger and Jim Mattis all be wrong? And when Walgreens put the Wellness Centers in stores, investors like Rupert Murdoch assumed that Walgreens must have done its due diligence. But they hadn't!

It's simply crazy that no one demanded to see an objective demonstration of the magic box. But that blind faith, as it turns out, is more a part of capitalism than we have been taught.

Do you think that Roger Parloff deserves any blame for the glowing Fortune story on Theranos, since he appears in the film to blame himself? Or was he just one more victim of Theranos's fraud?

He put her on the cover of Fortune so he deserves some blame for the fraud. He still blames himself. That willingness to hold himself to account shows how seriously he takes the job of a journalist. Unlike Elizabeth, Roger has the honesty and moral integrity to admit that he made a mistake. He owned up to it and published a mea culpa. That said, Roger was also a victim because Elizabeth lied to him.

Do you think investors in Silicon Valley, with their FOMO attitudes and deep pockets, are vulnerable to making the same mistake again with a shiny new startup, or has this saga been a sober reminder to do their due diligence first?

Many of the mistakes made with Theranos were the same mistakes made with Enron. We must learn to recognize that we are, by nature, trusting souls. Knowing that should lead us to a guiding slogan: "trust but verify."

The irony of Holmes dancing to "I Can't Touch This" is almost too perfect. How did you find that footage?

It was leaked to us.

"Elizabeth Holmes is now famous for her fraud. Who better to host the re-boot of 'The Apprentice.'"

Holmes is facing up to 20 years in prison for federal fraud charges, but Vanity Fair recently reported that she is seeking redemption, taking meetings with filmmakers for a possible documentary to share her "real" story. What do you think will become of Holmes in the long run?

It's usually a mistake to handicap a trial. My guess is that she will be convicted and do some prison time. But maybe she can convince jurors -- the way she convinced journalists, her board, and her investors -- that, on account of her noble intentions, she deserves to be found not guilty. "Somewhere, over the rainbow…"

After the trial, and possibly prison, I'm sure that EH will use her supporters (like Tim Draper) to find a way to use the virtual currency of her celebrity to rebrand herself and launch something new. Fitzgerald famously said that "there are no second acts in American lives." That may be the stupidest thing he ever said.

Donald Trump failed at virtually every business he ever embarked on. But he became a celebrity for being a fake businessman and used that celebrity -- and phony expertise -- to become president of the United States. Elizabeth Holmes is now famous for her fraud. Who better to host the re-boot of "The Apprentice." And then?

"You Can't Touch This!"

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

“Jurassic Park Without the Scary Parts” Is Actually Happening

Two of six female Southern white rhinos who were brought to the San Diego Safari Park to serve as surrogate mothers for the embryos that scientists hope to make from gametes from induced pluripotent stem cells.

[Editor's Note: This video is the first of a five-part series titled "The Future Is Now: The Revolutionary Power of Stem Cell Research." Produced in partnership with the Regenerative Medicine Foundation, and filmed at the annual 2019 World Stem Cell Summit, this series illustrates how stem cell research will profoundly impact life on earth. A new video will be published every Monday this month.]

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.