After Dobbs v. Jackson, the Battle Shifts to Digital Privacy v. Surveillance

The limits of digital privacy are becoming clearer in the post-Dobbs era, as a wide range of data sources can reveal online and offline activities, including whether a woman seeks an abortion.

Since the recent reversal of Roe v. Wade — the landmark decision establishing a constitutional right to abortion — the vulnerabilities of reproductive health data and various other information stored on digital devices or shared through the Web have risen to the forefront.

Menstrual period tracking apps are an example of how technologies that collect information from users could be weaponized against abortions seekers. The apps, which help tens of millions of users in the U.S. predict when they’re ovulating, may provide evidence that leads to criminal prosecution in states with abortion bans, says Anton T. Dahbura, executive director of the Johns Hopkins University Information Security Institute. In states where abortion is outlawed, “it’s probably best to not use a period tracker,” he says.

Following the Dobbs v. Jackson ruling in late June that overturned Roe, even women who suffered a miscarriage could be suspected of having an abortion in some cases. While using these apps in anonymous mode may appear more secure, “data is notoriously difficult to perfectly anonymize,” Dahbura says. “Whether the data are stored on the user’s device or in the cloud, there are ways to connect that data to the user.”

Completely concealing one’s tracks in cyberspace poses enormous challenges. Digital forensics can take advantage of technology such as GPS apps, security cameras, license plate trackers, credit card transactions and bank records to reconstruct a person’s activities,” Dahbura says. “Abortion service providers are also in a world of risk for similar reasons.”

Practicing “good cyber hygiene” is essential. That’s particularly true in states where private citizens may be rewarded for reporting on women they suspect of having an abortion, such as Texas, which passed a so-called bounty hunter law last fall. To help guard against hacking, Dahbura suggests using strong passwords and two-factor authentication when possible while remaining on alert for phishing scams on email or texts.

Another option for safeguarding privacy is to avoid such apps entirely, but that choice will depend on an individual’s analysis of the risks and benefits, says Leah Fowler, research assistant professor at the University of Houston Law Center, Health Law & Policy Institute.

“These apps are popular because people find them helpful and convenient, so I hesitate to tell anyone to get rid of something they like without more concrete evidence of its nefarious uses,” she says. “I also hate the idea that asking anyone capable of becoming pregnant to opt out of all or part of the digital economy could ever be a viable solution. That’s an enormous policy failure. We have to do better than that.”

The potential universe of abortion-relevant data can include information from a variety of fitness and other biometric trackers, text and social media chat records, call details, purchase histories and medical insurance records.

Instead, Fowler recommends that concerned consumers read the terms of service and privacy policies of the apps they’re using. If some of the terms are unclear, she suggests emailing customer service with questions until the answers are satisfactory. It’s also wise for consumers to research products that meet their specific needs and find out whether other women have raised concerns about specific apps. Users interested in more privacy may want to switch to an app that stores data locally, meaning the data stays on your device, or does not use third-party tracking, so the app-maker is the only company with access to it, she says.

Period tracking apps can be useful for those on fertility journeys, making it easier to store information digitally than on paper charts. But users may want to factor in whether they live in a state with an anti-abortion stance and run the risk of legal issues due to a potential data breach, says Carmel Shachar, executive director of the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics at Harvard Law School.

Consumers’ risks extend beyond period tracking apps in the post-Roe v. Wade era. “Anything that creates digital breadcrumbs to your reproductive choices and conduct could raise concerns — for example, googling ‘abortion providers near me’ or texting your best friend that you are pregnant but do not want to be,” Shachar says. Women also could incriminate themselves by bringing their phones, which may record geolocation data, to the clinic with them.

The potential universe of abortion-relevant data can include information from a variety of fitness and other biometric trackers, text and social media chat records, call details, purchase histories and medical insurance records, says Rebecca Wexler, faculty co-director of the Berkeley Center for Law & Technology. “These data sources can reveal a pregnant person’s decision to seek or obtain an abortion, as well as reveal a healthcare provider’s provision of abortion services and anyone else’s provision of abortion assistance,” she says.

In some situations, people or companies could inadvertently expose themselves to risk after posting on social media with offers of places for abortion seekers to stay after traveling from states with bans. They could be liable for aiding and abetting abortion. At this point, it’s unclear whether states that ban abortion will try to prosecute residents who seek abortions in other states without bans.

Another possibility is that a woman seeking an abortion will be prosecuted based not only on her phone’s data, but also on the data that law enforcement finds on someone else’s device or a shared computer. As a result, “people in one household may find themselves at odds with each other,” says K Royal, faculty fellow at the Center for Law, Science, and Innovation at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law. “This is a very delicate situation.”

Individuals and corporate executives should research their options before leaving a digital footprint. “Guard your privacy carefully, whether you are seeking help or you are seeking to help someone,” Royal says. While she has come across recommendations from other experts who suggest carrying a second phone that is harder to link a person’s identity for certain online activities, “it’s not practical on a general basis.”

The privacy of this health data isn’t fully protected by the law because period trackers, texting services and other apps are not healthcare providers — and as a result, there’s no prohibition on sharing the information with a third party under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, says Florencia Marotta-Wurgler, a professor who specializes in online consumer contracts and data privacy at the NYU School of Law.

“So, as long as there is valid consent, then it’s fair game unless you say that it violates the reasonable expectations of consumers,” she says. “But this is pretty unchartered territory at the moment.”

As states implement laws granting anyone the power to report suspected or known pregnancies to law enforcement, anti-choice activists are purchasing reproductive health data from companies that make period apps, says Rebecca Herold, chief executive officer of Privacy & Security Brainiacs in Des Moines, Iowa, and a member of the Emerging Trends Working Group at ISACA, an association focused on information technology governance. They could also buy data on search histories and make it available in places like Texas for “bounty hunters” to find out which women have searched for information about abortions.

Some groups are creating their own apps described as providing general medical information on subjects such as pregnancy health. But they are “ultimately intended to ‘catch’ women” — to identify those who are probably pregnant and dissuade them from having an abortion, to launch harassment campaigns against them, or to report them to law enforcement, anti-choice groups and others in states where such prenatal medical care procedures are now restricted or prohibited, Herold says.

In addition to privacy concerns, the reversal of Roe v. Wade raises censorship issues. Facebook and Instagram have started to remove or flag content, particularly as it relates to providing the abortion pill, says Michael Kleinman, director of the Silicon Valley Initiative at Amnesty International USA, a global organization that promotes human rights.

Facebook and Instagram have rules that forbid private citizens from buying, selling or giving away pharmaceuticals, including the abortion pill, according to a social media post by a communications director for Meta, which owns both platforms. In the same post, though, the Meta official noted that the company’s enforcement of this rule has been “incorrect” in some cases.

“It’s terrifying to think that arbitrary decisions by these platforms can dramatically limit the ability of people to access critical reproductive rights information,” Kleinman says. However, he adds, “as it currently stands, the platforms make unilateral decisions about what reproductive rights information they allow and what information they take down.”

Dr. May Edward Chinn, Kizzmekia Corbett, PhD., and Alice Ball, among others, have been behind some of the most important scientific work of the last century.

If you look back on the last century of scientific achievements, you might notice that most of the scientists we celebrate are overwhelmingly white, while scientists of color take a backseat. Since the Nobel Prize was introduced in 1901, for example, no black scientists have landed this prestigious award.

The work of black women scientists has gone unrecognized in particular. Their work uncredited and often stolen, black women have nevertheless contributed to some of the most important advancements of the last 100 years, from the polio vaccine to GPS.

Here are five black women who have changed science forever.

Dr. May Edward Chinn

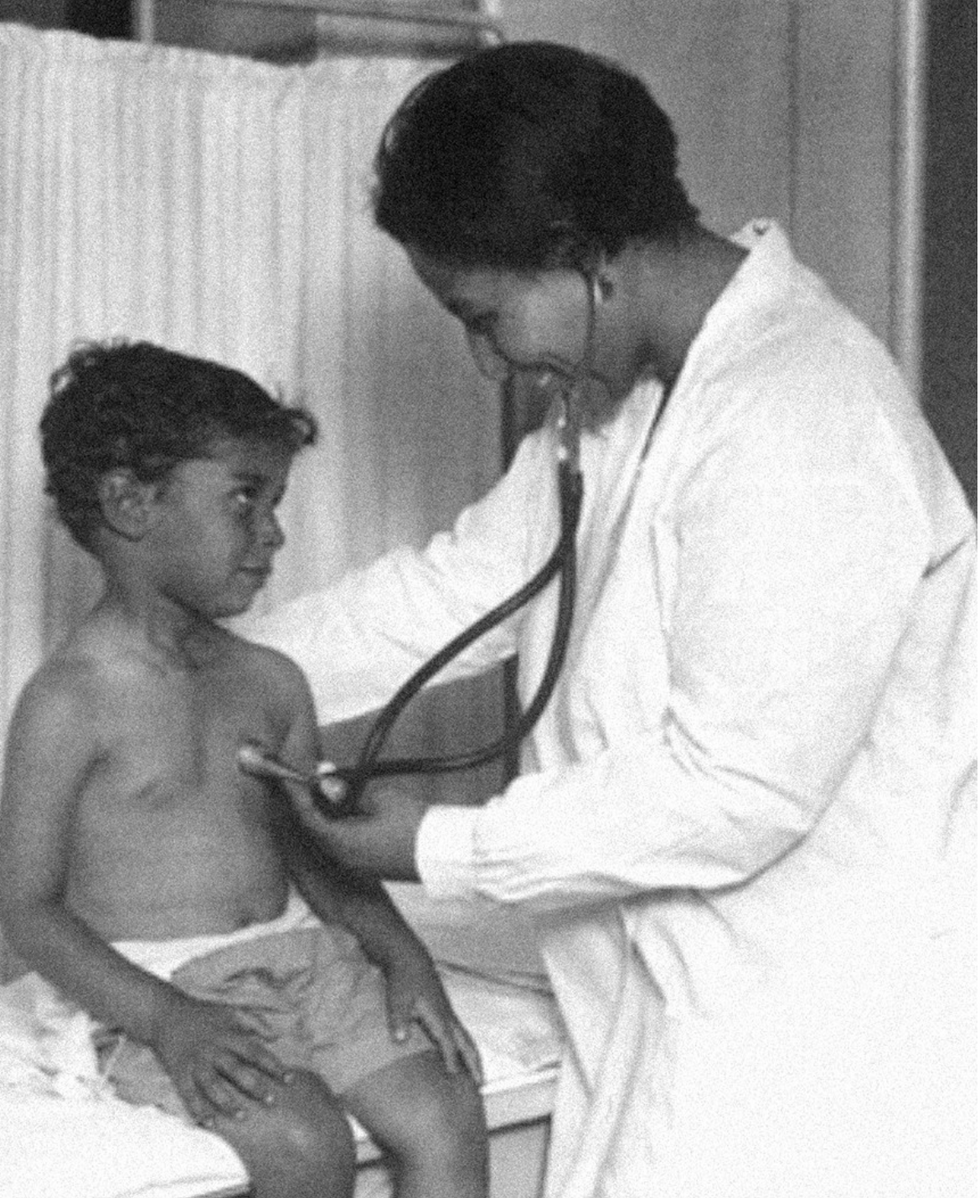

Dr. May Edward Chinn practicing medicine in Harlem

George B. Davis, PhD.

Chinn was born to poor parents in New York City just before the start of the 20th century. Although she showed great promise as a pianist, playing with the legendary musician Paul Robeson throughout the 1920s, she decided to study medicine instead. Chinn, like other black doctors of the time, were barred from studying or practicing in New York hospitals. So Chinn formed a private practice and made house calls, sometimes operating in patients’ living rooms, using an ironing board as a makeshift operating table.

Chinn worked among the city’s poor, and in doing this, started to notice her patients had late-stage cancers that often had gone undetected or untreated for years. To learn more about cancer and its prevention, Chinn begged information off white doctors who were willing to share with her, and even accompanied her patients to other clinic appointments in the city, claiming to be the family physician. Chinn took this information and integrated it into her own practice, creating guidelines for early cancer detection that were revolutionary at the time—for instance, checking patient health histories, checking family histories, performing routine pap smears, and screening patients for cancer even before they showed symptoms. For years, Chinn was the only black female doctor working in Harlem, and she continued to work closely with the poor and advocate for early cancer screenings until she retired at age 81.

Alice Ball

Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

Alice Ball was a chemist best known for her groundbreaking work on the development of the “Ball Method,” the first successful treatment for those suffering from leprosy during the early 20th century.

In 1916, while she was an undergraduate student at the University of Hawaii, Ball studied the effects of Chaulmoogra oil in treating leprosy. This oil was a well-established therapy in Asian countries, but it had such a foul taste and led to such unpleasant side effects that many patients refused to take it.

So Ball developed a method to isolate and extract the active compounds from Chaulmoogra oil to create an injectable medicine. This marked a significant breakthrough in leprosy treatment and became the standard of care for several decades afterward.

Unfortunately, Ball died before she could publish her results, and credit for this discovery was given to another scientist. One of her colleagues, however, was able to properly credit her in a publication in 1922.

Henrietta Lacks

onathan Newton/The Washington Post/Getty

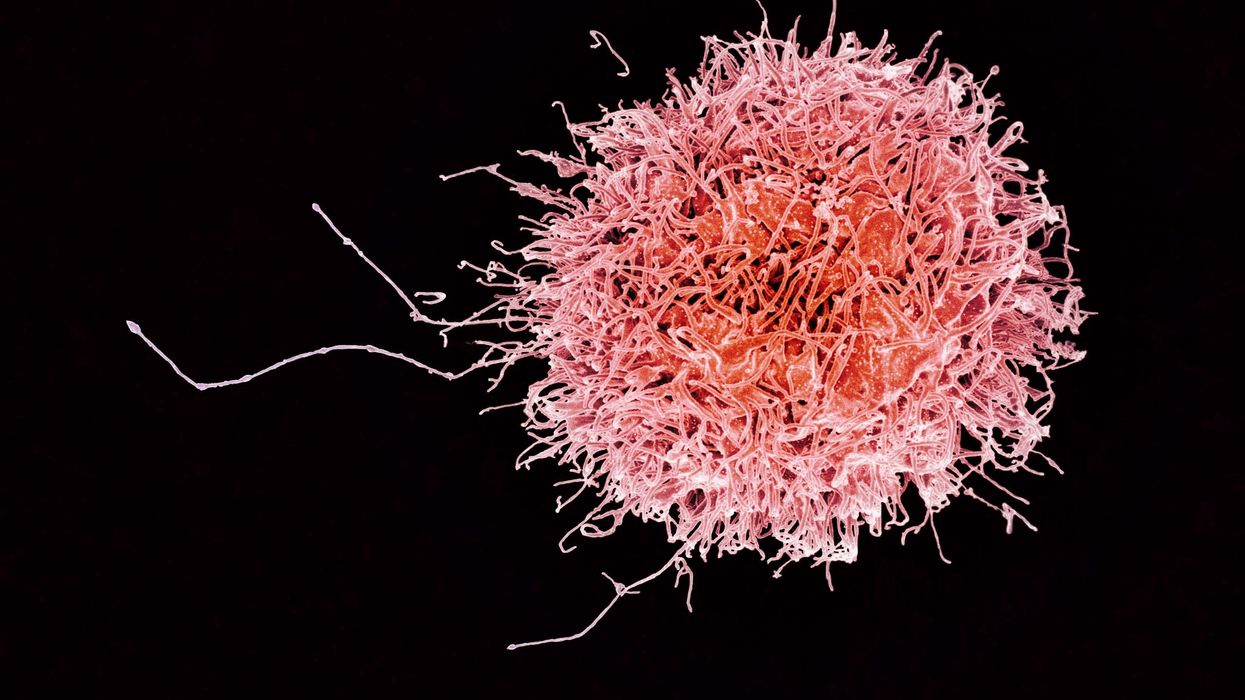

The person who arguably contributed the most to scientific research in the last century, surprisingly, wasn’t even a scientist. Henrietta Lacks was a tobacco farmer and mother of five children who lived in Maryland during the 1940s. In 1951, Lacks visited Johns Hopkins Hospital where doctors found a cancerous tumor on her cervix. Before treating the tumor, the doctor who examined Lacks clipped two small samples of tissue from Lacks’ cervix without her knowledge or consent—something unthinkable today thanks to informed consent practices, but commonplace back then.

As Lacks underwent treatment for her cancer, her tissue samples made their way to the desk of George Otto Gey, a cancer researcher at Johns Hopkins. He noticed that unlike the other cell cultures that came into his lab, Lacks’ cells grew and multiplied instead of dying out. Lacks’ cells were “immortal,” meaning that because of a genetic defect, they were able to reproduce indefinitely as long as certain conditions were kept stable inside the lab.

Gey started shipping Lacks’ cells to other researchers across the globe, and scientists were thrilled to have an unlimited amount of sturdy human cells with which to experiment. Long after Lacks died of cervical cancer in 1951, her cells continued to multiply and scientists continued to use them to develop cancer treatments, to learn more about HIV/AIDS, to pioneer fertility treatments like in vitro fertilization, and to develop the polio vaccine. To this day, Lacks’ cells have saved an estimated 10 million lives, and her family is beginning to get the compensation and recognition that Henrietta deserved.

Dr. Gladys West

Andre West

Gladys West was a mathematician who helped invent something nearly everyone uses today. West started her career in the 1950s at the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division in Virginia, and took data from satellites to create a mathematical model of the Earth’s shape and gravitational field. This important work would lay the groundwork for the technology that would later become the Global Positioning System, or GPS. West’s work was not widely recognized until she was honored by the US Air Force in 2018.

Dr. Kizzmekia "Kizzy" Corbett

TIME Magazine

At just 35 years old, immunologist Kizzmekia “Kizzy” Corbett has already made history. A viral immunologist by training, Corbett studied coronaviruses at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and researched possible vaccines for coronaviruses such as SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome).

At the start of the COVID pandemic, Corbett and her team at the NIH partnered with pharmaceutical giant Moderna to develop an mRNA-based vaccine against the virus. Corbett’s previous work with mRNA and coronaviruses was vital in developing the vaccine, which became one of the first to be authorized for emergency use in the United States. The vaccine, along with others, is responsible for saving an estimated 14 million lives.On today’s episode of Making Sense of Science, I’m honored to be joined by Dr. Paul Song, a physician, oncologist, progressive activist and biotech chief medical officer. Through his company, NKGen Biotech, Dr. Song is leveraging the power of patients’ own immune systems by supercharging the body’s natural killer cells to make new treatments for Alzheimer’s and cancer.

Whereas other treatments for Alzheimer’s focus directly on reducing the build-up of proteins in the brain such as amyloid and tau in patients will mild cognitive impairment, NKGen is seeking to help patients that much of the rest of the medical community has written off as hopeless cases, those with late stage Alzheimer’s. And in small studies, NKGen has shown remarkable results, even improvement in the symptoms of people with these very progressed forms of Alzheimer’s, above and beyond slowing down the disease.

In the realm of cancer, Dr. Song is similarly setting his sights on another group of patients for whom treatment options are few and far between: people with solid tumors. Whereas some gradual progress has been made in treating blood cancers such as certain leukemias in past few decades, solid tumors have been even more of a challenge. But Dr. Song’s approach of using natural killer cells to treat solid tumors is promising. You may have heard of CAR-T, which uses genetic engineering to introduce cells into the body that have a particular function to help treat a disease. NKGen focuses on other means to enhance the 40 plus receptors of natural killer cells, making them more receptive and sensitive to picking out cancer cells.

Paul Y. Song, MD is currently CEO and Vice Chairman of NKGen Biotech. Dr. Song’s last clinical role was Asst. Professor at the Samuel Oschin Cancer Center at Cedars Sinai Medical Center.

Dr. Song served as the very first visiting fellow on healthcare policy in the California Department of Insurance in 2013. He is currently on the advisory board of the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago and a board member of Mercy Corps, The Center for Health and Democracy, and Gideon’s Promise.

Dr. Song graduated with honors from the University of Chicago and received his MD from George Washington University. He completed his residency in radiation oncology at the University of Chicago where he served as Chief Resident and did a brachytherapy fellowship at the Institute Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France. He was also awarded an ASTRO research fellowship in 1995 for his research in radiation inducible gene therapy.

With Dr. Song’s leadership, NKGen Biotech’s work on natural killer cells represents cutting-edge science leading to key findings and important pieces of the puzzle for treating two of humanity’s most intractable diseases.

Show links

- Paul Song LinkedIn

- NKGen Biotech on Twitter - @NKGenBiotech

- NKGen Website: https://nkgenbiotech.com/

- NKGen appoints Paul Song

- Patient Story: https://pix11.com/news/local-news/long-island/promising-new-treatment-for-advanced-alzheimers-patients/

- FDA Clearance: https://nkgenbiotech.com/nkgen-biotech-receives-ind-clearance-from-fda-for-snk02-allogeneic-natural-killer-cell-therapy-for-solid-tumors/Q3 earnings data: https://www.nasdaq.com/press-release/nkgen-biotech-inc.-reports-third-quarter-2023-financial-results-and-business