Saliva May Help Diagnose PTSD in Veterans

A recent study finds that former soldiers with post traumatic stress disorders have a certain set of bacteria in their saliva, a distinct signature that is believed to be the first biological marker for PTSD.

As a bioinformatician and young veteran, Guy Shapira welcomed the opportunity to help with conducting a study to determine if saliva can reveal if war veterans have post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD.

The research team, which drew mostly from Tel Aviv University’s Sackler Faculty of Medicine and Sagol School of Neuroscience, collected saliva samples from approximately 200 veterans who suffered psychological trauma stemming from the years they spent fighting in the First Lebanon War in 1982. The researchers also characterized the participants’ psychological, social and medical conditions, including a detailed analysis of their microbiomes.

They found that the former soldiers with PTSD have a certain set of bacteria in their saliva, a distinct microbiotic signature that is believed to be the first biological marker for PTSD. The finding suggests that, in the future, saliva tests could be used to help identify this disorder. As of now, PTSD is often challenging to diagnose.

Shapira, a Ph.D. student at Tel Aviv University, was responsible for examining genetic and health-related data of the veterans who participated – information that had been compiled steadily over four decades. The veterans provided this data voluntarily, Shapira says, at least partly because the study carries important implications for their own psychological health.

The research was led by Illana Gozes, professor emerita of clinical biochemistry. “We looked at the bacteria in their blood and their saliva,” Gozes explains. To discover the microbial signatures, they analyzed the biometric data for each soldier individually and as a group. Comparing the results of the participants’ microbial distribution to the results of their psychological examinations and their responses to personal welfare questionnaires, the researchers learned that veterans with PTSD – and, more generally, those with significant mental health issues – have the same bacterial content in their saliva.

“Having empirical metrics to assess whether or not someone has PTSD can help veterans who make their case to the Army to get reparations,” Shapira says.

More research is required to support this finding, published in July in Nature’s prestigious Molecular Psychiatry, but it could have important implications for identifying people with PTSD. Currently, it can be diagnosed only through psychological and behavioral symptoms such as flashbacks, nightmares, sleep disorders, increased irritability and physical aggressiveness. Veterans sometimes don’t report these symptoms to health providers or realize they’re related to the trauma they experienced during combat.

The researchers also identified a correlation that indicates people with a higher level of education show a lower occurrence of the microbiotic signature linked to PTSD, while people who experienced greater exposure to air pollution show a higher occurrence of this signature. That confirms their finding that the veterans’ health is dependent on their individual biology combined with the conditions of their environment.

“Thanks to this study, it may be possible in the future to use objective molecular and biological characteristics to distinguish PTSD sufferers, taking into account environmental influences,” Gozes said in an article in Israel21c. “We hope that this new discovery and the microbial signatures described in this study might promote easier diagnosis of post-traumatic stress in soldiers so they can receive appropriate treatment.”

Gozes added that roughly a third of the subjects in their study hadn’t been diagnosed with PTSD previously. That meant they had never received any support from Israel’s Ministry of Defense or other officials for treatment and reparations, the payments to compensate for injuries sustained during war.

Shapira’s motivation to participate in this study is personal as well as professional: in addition to being veteran himself, his father served in the First Lebanon War. “Fortunately, he did not develop any PTSD, despite being shot in the foot...some of his friends died, so it wasn’t easy on him,” says Shapira.

“Having empirical metrics to assess whether or not someone has PTSD can help veterans who make their case to the Army to get reparations,” Shapira says. “It is a very difficult and demanding process, so the more empirical metrics we have to assess PTSD, the less people will have to suffer in these committees and unending examinations that are mostly pitched against the veterans because the state is trying to avoid spending too much money.”

DNA gathered from animal poop helps protect wildlife

Alida de Flamingh and her team are collecting elephant dung. It holds a trove of information about animal health, diet and genetic diversity.

On the savannah near the Botswana-Zimbabwe border, elephants grazed contentedly. Nearby, postdoctoral researcher Alida de Flamingh watched and waited. As the herd moved away, she went into action, collecting samples of elephant dung that she and other wildlife conservationists would study in the months to come. She pulled on gloves, took a swab, and ran it all over the still-warm, round blob of elephant poop.

Sequencing DNA from fecal matter is a safe, non-invasive way to track and ultimately help protect over 42,000 species currently threatened by extinction. Scientists are using this DNA to gain insights into wildlife health, genetic diversity and even the broader environment. Applied to elephants, chimpanzees, toucans and other species, it helps scientists determine the genetic diversity of groups and linkages with other groups. Such analysis can show changes in rates of inbreeding. Populations with greater genetic diversity adapt better to changes and environmental stressors than those with less diversity, thus reducing their risks of extinction, explains de Flamingh, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Analyzing fecal DNA also reveals information about an animal’s diet and health, and even nearby flora that is eaten. That information gives scientists broader insights into the ecosystem, and the findings are informing conservation initiatives. Examples include restoring or maintaining genetic connections among groups, ensuring access to certain foraging areas or increasing diversity in captive breeding programs.

Approximately 27 percent of mammals and 28 percent of all assessed species are close to dying out. The IUCN Red List of threatened species, simply called the Red List, is the world’s most comprehensive record of animals’ risk of extinction status. The more information scientists gather, the better their chances of reducing those risks. In Africa, populations of vertebrates declined 69 percent between 1970 and 2022, according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

“We put on sterile gloves and use a sterile swab to collect wet mucus and materials from the outside of the dung ball,” says Alida de Flamingh, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

“When people talk about species, they often talk about ecosystems, but they often overlook genetic diversity,” says Christina Hvilsom, senior geneticist at the Copenhagen Zoo. “It’s easy to count (individuals) to assess whether the population size is increasing or decreasing, but diversity isn’t something we can see with our bare eyes. Yet, it’s actually the foundation for the species and populations.” DNA analysis can provide this critical information.

Assessing elephants’ health

“Africa’s elephant populations are facing unprecedented threats,” says de Flamingh, the postdoc, who has studied them since 2009. Challenges include ivory poaching, habitat destruction and smaller, more fragmented habitats that result in smaller mating pools with less genetic diversity. Additionally, de Flamingh studies the microbial communities living on and in elephants – their microbiomes – looking for parasites or dangerous microbes.

Approximately 415,000 elephants inhabit Africa today, but de Flamingh says the number would be four times higher without these challenges. The IUCN Red List reports African savannah elephants are endangered and African forest elephants are critically endangered. Elephants support ecosystem biodiversity by clearing paths that help other species travel. Their very footprints create small puddles that can host smaller organisms such as tadpoles. Elephants are often described as ecosystems’ engineers, so if they disappear, the rest of the ecosystem will suffer too.

There’s a process to collecting elephant feces. “We put on sterile gloves (which we change for each sample) and use a sterile swab to collect wet mucus and materials from the outside of the dung ball,” says de Flamingh. They rub a sample about the size of a U.S. quarter onto a paper card embedded with DNA preservation technology. Each card is air dried and stored in a packet of desiccant to prevent mold growth. This way, samples can be stored at room temperature indefinitely without the DNA degrading.

Earlier methods required collecting dung in bags, which needed either refrigeration or the addition of preservatives, or the riskier alternative of tranquilizing the animals before approaching them to draw blood samples. The ability to collect and sequence the DNA made things much easier and safer.

“Our research provides a way to assess elephant health without having to physically interact with elephants,” de Flamingh emphasizes. “We also keep track of the GPS coordinates of each sample so that we can create a map of the sampling locations,” she adds. That helps researchers correlate elephants’ health with geographic areas and their conditions.

Although de Flamingh works with elephants in the wild, the contributions of zoos in the United States and collaborations in South Africa (notably the late Professor Rudi van Aarde and the Conservation Ecology Research Unit at the University of Pretoria) were key in studying this method to ensure it worked, she points out.

Protecting chimpanzees

Genetic work with chimpanzees began about a decade ago. Hvilsom and her group at the Copenhagen Zoo analyzed DNA from nearly 1,000 fecal samples collected between 2003 and 2018 by a team of international researchers. The goal was to assess the status of the West African subspecies, which is critically endangered after rapid population declines. Of the four subspecies of chimpanzees, the West African subspecies is considered the most at-risk.

In total, the WWF estimates the numbers of chimpanzees inhabiting Africa’s forests and savannah woodlands at between 173,000 and 300,000. Poaching, disease and human-caused changes to their lands are their major risks.

By analyzing genetics obtained from fecal samples, Hvilsom estimated the chimpanzees’ population, ascertained their family relationships and mapped their migration routes.

“One of the threats is mining near the Nimba Mountains in Guinea,” a stronghold for the West African subspecies, Hvilsom says. The Nimba Mountains are a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but they are rich in iron ore, which is used to make the steel that is vital to the Asian construction boom. As she and colleagues wrote in a recent paper, “Many extractive industries are currently developing projects in chimpanzee habitat.”

Analyzing DNA allows researchers to identify individual chimpanzees more accurately than simply observing them, she says. Normally, field researchers would install cameras and manually inspect each picture to determine how many chimpanzees were in an area. But, Hvilsom says, “That’s very tricky. Chimpanzees move a lot and are fast, so it’s difficult to get clear pictures. Often, they find and destroy the cameras. Also, they live in large areas, so you need a lot of cameras.”

By analyzing genetics obtained from fecal samples, Hvilsom estimated the chimpanzees’ population, ascertained their family relationships and mapped their migration routes based upon DNA comparisons with other chimpanzee groups. The mining companies and builders are using this information to locate future roads where they won’t disrupt migration – a more effective solution than trying to build artificial corridors for wildlife.

“The current route cuts off communities of chimpanzees,” Hvilsom elaborates. That effectively prevents young adult chimps from joining other groups when the time comes, eventually reducing the currently-high levels of genetic diversity.

“The mining company helped pay for the genetics work,” Hvilsom says, “as part of its obligation to assess and monitor biodiversity and the effect of the mining in the area.”

Of 50 toucan subspecies, 11 are threatened or near-threatened with extinction because of deforestation and poaching.

Identifying toucan families

Feces aren't the only substance researchers draw DNA samples from. Jeffrey Coleman, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Texas at Austin relies on blood tests for studying the genetic diversity of toucans---birds species native to Central America and nearby regions. They live in the jungles, where they hop among branches, snip fruit from trees, toss it in the air and catch it with their large beaks. “Toucans are beautiful, charismatic birds that are really important to the ecosystem,” says Coleman.

Of their 50 subspecies, 11 are threatened or near-threatened with extinction because of deforestation and poaching. “When people see these aesthetically pleasing birds, they’re motivated to care about conservation practices,” he points out.

Coleman works with the Dallas World Aquarium and its partner zoos to analyze DNA from blood draws, using it to identify which toucans are related and how closely. His goal is to use science to improve the genetic diversity among toucan offspring.

Specifically, he’s looking at sections of the genome of captive birds in which the nucleotides repeat multiple times, such as AGATAGATAGAT. Called microsatellites, these consecutively-repeating sections can be passed from parents to children, helping scientists identify parent-child and sibling-sibling relationships. “That allows you to make strategic decisions about how to pair (captive) individuals for mating...to avoid inbreeding,” Coleman says.

Jeffrey Coleman is studying the microsatellites inside the toucan genomes.

Courtesy Jeffrey Coleman

The alternative is to use a type of analysis that looks for a single DNA building block – a nucleotide – that differs in a given sequence. Called single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs, pronounced “snips”), they are very common and very accurate. Coleman says they are better than microsatellites for some uses. But scientists have already developed a large body of microsatellite data from multiple species, so microsatellites can shed more insights on relations.

Regardless of whether conservation programs use SNPs or microsatellites to guide captive breeding efforts, the goal is to help them build genetically diverse populations that eventually may supplement endangered populations in the wild. “The hope is that the ecosystem will be stable enough and that the populations (once reintroduced into the wild) will be able to survive and thrive,” says Coleman. History knows some good examples of captive breeding success.

The California condor, which had a total population of 27 in 1987, when the last wild birds were captured, is one of them. A captive breeding program boosted their numbers to 561 by the end of 2022. Of those, 347 of those are in the wild, according to the National Park Service.

Conservationists hope that their work on animals’ genetic diversity will help preserve and restore endangered species in captivity and the wild. DNA analysis is crucial to both types of efforts. The ability to apply genome sequencing to wildlife conservation brings a new level of accuracy that helps protect species and gives fresh insights that observation alone can’t provide.

“A lot of species are threatened,” Coleman says. “I hope this research will be a resource people can use to get more information on longer-term genealogies and different populations.”

DNA- and RNA-based electronic implants may revolutionize healthcare

The test tubes contain tiny DNA/enzyme-based circuits, which comprise TRUMPET, a new type of electronic device, smaller than a cell.

Implantable electronic devices can significantly improve patients’ quality of life. A pacemaker can encourage the heart to beat more regularly. A neural implant, usually placed at the back of the skull, can help brain function and encourage higher neural activity. Current research on neural implants finds them helpful to patients with Parkinson’s disease, vision loss, hearing loss, and other nerve damage problems. Several of these implants, such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink, have already been approved by the FDA for human use.

Yet, pacemakers, neural implants, and other such electronic devices are not without problems. They require constant electricity, limited through batteries that need replacements. They also cause scarring. “The problem with doing this with electronics is that scar tissue forms,” explains Kate Adamala, an assistant professor of cell biology at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. “Anytime you have something hard interacting with something soft [like muscle, skin, or tissue], the soft thing will scar. That's why there are no long-term neural implants right now.” To overcome these challenges, scientists are turning to biocomputing processes that use organic materials like DNA and RNA. Other promised benefits include “diagnostics and possibly therapeutic action, operating as nanorobots in living organisms,” writes Evgeny Katz, a professor of bioelectronics at Clarkson University, in his book DNA- And RNA-Based Computing Systems.

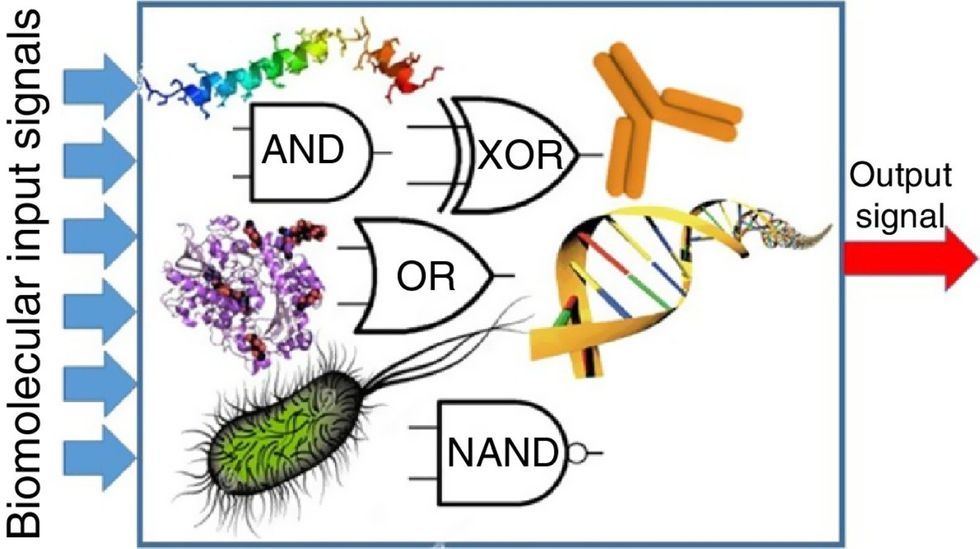

While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output.

Adamala’s research focuses on developing such biocomputing systems using DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids. Using these molecules in the biocomputing systems allows the latter to be biocompatible with the human body, resulting in a natural healing process. In a recent Nature Communications study, Adamala and her team created a new biocomputing platform called TRUMPET (Transcriptional RNA Universal Multi-Purpose GatE PlaTform) which acts like a DNA-powered computer chip. “These biological systems can heal if you design them correctly,” adds Adamala. “So you can imagine a computer that will eventually heal itself.”

The basics of biocomputing

Biocomputing and regular computing have many similarities. Like regular computing, biocomputing works by running information through a series of gates, usually logic gates. A logic gate works as a fork in the road for an electronic circuit. The input will travel one way or another, giving two different outputs. An example logic gate is the AND gate, which has two inputs (A and B) and two different results. If both A and B are 1, the AND gate output will be 1. If only A is 1 and B is 0, the output will be 0 and vice versa. If both A and B are 0, the result will be 0. While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output. In this case, the DNA enters the logic gate as a single or double strand.

If the DNA is double-stranded, the system “digests” the DNA or destroys it, which results in non-fluorescence or “0” output. Conversely, if the DNA is single-stranded, it won’t be digested and instead will be copied by several enzymes in the biocomputing system, resulting in fluorescent RNA or a “1” output. And the output for this type of binary system can be expanded beyond fluorescence or not. For example, a “1” output might be the production of the enzyme insulin, while a “0” may be that no insulin is produced. “This kind of synergy between biology and computation is the essence of biocomputing,” says Stephanie Forrest, a professor and the director of the Biodesign Center for Biocomputing, Security and Society at Arizona State University.

Biocomputing circles are made of DNA, RNA, proteins and even bacteria.

Evgeny Katz

The TRUMPET’s promise

Depending on whether the biocomputing system is placed directly inside a cell within the human body, or run in a test-tube, different environmental factors play a role. When an output is produced inside a cell, the cell's natural processes can amplify this output (for example, a specific protein or DNA strand), creating a solid signal. However, these cells can also be very leaky. “You want the cells to do the thing you ask them to do before they finish whatever their businesses, which is to grow, replicate, metabolize,” Adamala explains. “However, often the gate may be triggered without the right inputs, creating a false positive signal. So that's why natural logic gates are often leaky." While biocomputing outside a cell in a test tube can allow for tighter control over the logic gates, the outputs or signals cannot be amplified by a cell and are less potent.

TRUMPET, which is smaller than a cell, taps into both cellular and non-cellular biocomputing benefits. “At its core, it is a nonliving logic gate system,” Adamala states, “It's a DNA-based logic gate system. But because we use enzymes, and the readout is enzymatic [where an enzyme replicates the fluorescent RNA], we end up with signal amplification." This readout means that the output from the TRUMPET system, a fluorescent RNA strand, can be replicated by nearby enzymes in the platform, making the light signal stronger. "So it combines the best of both worlds,” Adamala adds.

These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body.

The TRUMPET biocomputing process is relatively straightforward. “If the DNA [input] shows up as single-stranded, it will not be digested [by the logic gate], and you get this nice fluorescent output as the RNA is made from the single-stranded DNA, and that's a 1,” Adamala explains. "And if the DNA input is double-stranded, it gets digested by the enzymes in the logic gate, and there is no RNA created from the DNA, so there is no fluorescence, and the output is 0." On the story's leading image above, if the tube is "lit" with a purple color, that is a binary 1 signal for computing. If it's "off" it is a 0.

While still in research, TRUMPET and other biocomputing systems promise significant benefits to personalized healthcare and medicine. These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body. The study’s lead author and graduate student Judee Sharon is already beginning to research TRUMPET's ability for earlier cancer diagnoses. Because the inputs for TRUMPET are single or double-stranded DNA, any mutated or cancerous DNA could theoretically be detected from the platform through the biocomputing process. Theoretically, devices like TRUMPET could be used to detect cancer and other diseases earlier.

Adamala sees TRUMPET not only as a detection system but also as a potential cancer drug delivery system. “Ideally, you would like the drug only to turn on when it senses the presence of a cancer cell. And that's how we use the logic gates, which work in response to inputs like cancerous DNA. Then the output can be the production of a small molecule or the release of a small molecule that can then go and kill what needs killing, in this case, a cancer cell. So we would like to develop applications that use this technology to control the logic gate response of a drug’s delivery to a cell.”

Although platforms like TRUMPET are making progress, a lot more work must be done before they can be used commercially. “The process of translating mechanisms and architecture from biology to computing and vice versa is still an art rather than a science,” says Forrest. “It requires deep computer science and biology knowledge,” she adds. “Some people have compared interdisciplinary science to fusion restaurants—not all combinations are successful, but when they are, the results are remarkable.”