Scientists Are Building an “AccuWeather” for Germs to Predict Your Risk of Getting the Flu

A future app may help you avoid getting the flu by informing you of your local risk on a given day.

Applied mathematician Sara del Valle works at the U.S.'s foremost nuclear weapons lab: Los Alamos. Once colloquially called Atomic City, it's a hidden place 45 minutes into the mountains northwest of Santa Fe. Here, engineers developed the first atomic bomb.

Like AccuWeather, an app for disease prediction could help people alter their behavior to live better lives.

Today, Los Alamos still a small science town, though no longer a secret, nor in the business of building new bombs. Instead, it's tasked with, among other things, keeping the stockpile of nuclear weapons safe and stable: not exploding when they're not supposed to (yes, please) and exploding if someone presses that red button (please, no).

Del Valle, though, doesn't work on any of that. Los Alamos is also interested in other kinds of booms—like the explosion of a contagious disease that could take down a city. Predicting (and, ideally, preventing) such epidemics is del Valle's passion. She hopes to develop an app that's like AccuWeather for germs: It would tell you your chance of getting the flu, or dengue or Zika, in your city on a given day. And like AccuWeather, it could help people alter their behavior to live better lives, whether that means staying home on a snowy morning or washing their hands on a sickness-heavy commute.

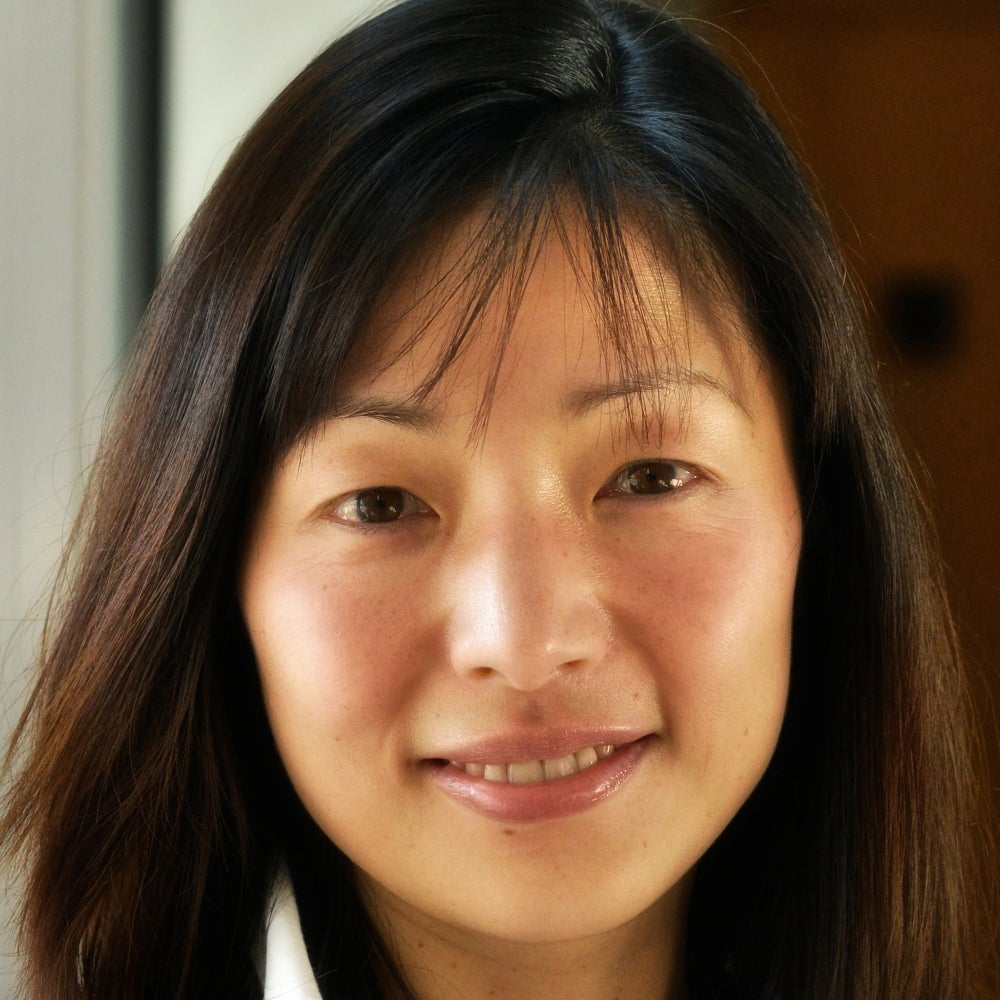

Sara del Valle of Los Alamos is working to predict and prevent epidemics using data and machine learning.

Since the beginning of del Valle's career, she's been driven by one thing: using data and predictions to help people behave practically around pathogens. As a kid, she'd always been good at math, but when she found out she could use it to capture the tentacular spread of disease, and not just manipulate abstractions, she was hooked.

When she made her way to Los Alamos, she started looking at what people were doing during outbreaks. Using social media like Twitter, Google search data, and Wikipedia, the team started to sift for trends. Were people talking about hygiene, like hand-washing? Or about being sick? Were they Googling information about mosquitoes? Searching Wikipedia for symptoms? And how did those things correlate with the spread of disease?

It was a new, faster way to think about how pathogens propagate in the real world. Usually, there's a 10- to 14-day lag in the U.S. between when doctors tap numbers into spreadsheets and when that information becomes public. By then, the world has moved on, and so has the disease—to other villages, other victims.

"We found there was a correlation between actual flu incidents in a community and the number of searches online and the number of tweets online," says del Valle. That was when she first let herself dream about a real-time forecast, not a 10-days-later backcast. Del Valle's group—computer scientists, mathematicians, statisticians, economists, public health professionals, epidemiologists, satellite analysis experts—has continued to work on the problem ever since their first Twitter parsing, in 2011.

They've had their share of outbreaks to track. Looking back at the 2009 swine flu pandemic, they saw people buying face masks and paying attention to the cleanliness of their hands. "People were talking about whether or not they needed to cancel their vacation," she says, and also whether pork products—which have nothing to do with swine flu—were safe to buy.

At the latest meeting with all the prediction groups, del Valle's flu models took first and second place.

They watched internet conversations during the measles outbreak in California. "There's a lot of online discussion about anti-vax sentiment, and people trying to convince people to vaccinate children and vice versa," she says.

Today, they work on predicting the spread of Zika, Chikungunya, and dengue fever, as well as the plain old flu. And according to the CDC, that latter effort is going well.

Since 2015, the CDC has run the Epidemic Prediction Initiative, a competition in which teams like de Valle's submit weekly predictions of how raging the flu will be in particular locations, along with other ailments occasionally. Michael Johannson is co-founder and leader of the program, which began with the Dengue Forecasting Project. Its goal, he says, was to predict when dengue cases would blow up, when previously an area just had a low-level baseline of sick people. "You'll get this massive epidemic where all of a sudden, instead of 3,000 to 4,000 cases, you have 20,000 cases," he says. "They kind of come out of nowhere."

But the "kind of" is key: The outbreaks surely come out of somewhere and, if scientists applied research and data the right way, they could forecast the upswing and perhaps dodge a bomb before it hit big-time. Questions about how big, when, and where are also key to the flu.

A big part of these projects is the CDC giving the right researchers access to the right information, and the structure to both forecast useful public-health outcomes and to compare how well the models are doing. The extra information has been great for the Los Alamos effort. "We don't have to call departments and beg for data," says del Valle.

When data isn't available, "proxies"—things like symptom searches, tweets about empty offices, satellite images showing a green, wet, mosquito-friendly landscape—are helpful: You don't have to rely on anyone's health department.

At the latest meeting with all the prediction groups, del Valle's flu models took first and second place. But del Valle wants more than weekly numbers on a government website; she wants that weather-app-inspired fortune-teller, incorporating the many diseases you could get today, standing right where you are. "That's our dream," she says.

This plot shows the the correlations between the online data stream, from Wikipedia, and various infectious diseases in different countries. The results of del Valle's predictive models are shown in brown, while the actual number of cases or illness rates are shown in blue.

(Courtesy del Valle)

The goal isn't to turn you into a germophobic agoraphobe. It's to make you more aware when you do go out. "If you know it's going to rain today, you're more likely to bring an umbrella," del Valle says. "When you go on vacation, you always look at the weather and make sure you bring the appropriate clothing. If you do the same thing for diseases, you think, 'There's Zika spreading in Sao Paulo, so maybe I should bring even more mosquito repellent and bring more long sleeves and pants.'"

They're not there yet (don't hold your breath, but do stop touching your mouth). She estimates it's at least a decade away, but advances in machine learning could accelerate that hypothetical timeline. "We're doing baby steps," says del Valle, starting with the flu in the U.S., dengue in Brazil, and other efforts in Colombia, Ecuador, and Canada. "Going from there to forecasting all diseases around the globe is a long way," she says.

But even AccuWeather started small: One man began predicting weather for a utility company, then helping ski resorts optimize their snowmaking. His influence snowballed, and now private forecasting apps, including AccuWeather's, populate phones across the planet. The company's progression hasn't been without controversy—privacy incursions, inaccuracy of long-term forecasts, fights with the government—but it has continued, for better and for worse.

Disease apps, perhaps spun out of a small, unlikely team at a nuclear-weapons lab, could grow and breed in a similar way. And both the controversies and public-health benefits that may someday spin out of them lie in the future, impossible to predict with certainty.

Biohackers Made a Cheap and Effective Home Covid Test -- But No One Is Allowed to Use It

A stock image of a home test for COVID-19.

Last summer, when fast and cheap Covid tests were in high demand and governments were struggling to manufacture and distribute them, a group of independent scientists working together had a bit of a breakthrough.

Working on the Just One Giant Lab platform, an online community that serves as a kind of clearing house for open science researchers to find each other and work together, they managed to create a simple, one-hour Covid test that anyone could take at home with just a cup of hot water. The group tested it across a network of home and professional laboratories before being listed as a semi-finalist team for the XPrize, a competition that rewards innovative solutions-based projects. Then, the group hit a wall: they couldn't commercialize the test.

They wanted to keep their project open source, making it accessible to people around the world, so they decided to forgo traditional means of intellectual property protection and didn't seek patents. (They couldn't afford lawyers anyway). And, as a loose-knit group that was not supported by a traditional scientific institution, working in community labs and homes around the world, they had no access to resources or financial support for manufacturing or distributing their test at scale.

But without ethical and regulatory approval for clinical testing, manufacture, and distribution, they were legally unable to create field tests for real people, leaving their inexpensive, $16-per-test, innovative product languishing behind, while other, more expensive over-the-counter tests made their way onto the market.

Who Are These Radical Scientists?

Independent, decentralized biomedical research has come of age. Also sometimes called DIYbio, biohacking, or community biology, depending on whom you ask, open research is today a global movement with thousands of members, from scientists with advanced degrees to middle-grade students. Their motivations and interests vary across a wide spectrum, but transparency and accessibility are key to the ethos of the movement. Teams are agile, focused on shoestring-budget R&D, and aim to disrupt business as usual in the ivory towers of the scientific establishment.

Ethics oversight is critical to ensuring that research is conducted responsibly, even by biohackers.

Initiatives developed within the community, such as Open Insulin, which hopes to engineer processes for affordable, small-batch insulin production, "Slybera," a provocative attempt to reverse engineer a $1 million dollar gene therapy, and the hundreds of projects posted on the collaboration platform Just One Giant Lab during the pandemic, all have one thing in common: to pursue testing in humans, they need an ethics oversight mechanism.

These groups, most of which operate collaboratively in community labs, homes, and online, recognize that some sort of oversight or guidance is useful—and that it's the right thing to do.

But also, and perhaps more immediately, they need it because federal rules require ethics oversight of any biomedical research that's headed in the direction of the consumer market. In addition, some individuals engaged in this work do want to publish their research in traditional scientific journals, which—you guessed it—also require that research has undergone an ethics evaluation. Ethics oversight is critical to ensuring that research is conducted responsibly, even by biohackers.

Bridging the Ethics Gap

The problem is that traditional oversight mechanisms, such as institutional review boards at government or academic research institutions, as well as the private boards utilized by pharmaceutical companies, are not accessible to most independent researchers. Traditional review boards are either closed to the public, or charge fees that are out of reach for many citizen science initiatives. This has created an "ethics gap" in nontraditional scientific research.

Biohackers are seen in some ways as the direct descendents of "white hat" computer hackers, or those focused on calling out security holes and contributing solutions to technical problems within self-regulating communities. In the case of health and biotechnology, those problems include both the absence of treatments and the availability of only expensive treatments for certain conditions. As the DIYbio community grows, there needs to be a way to provide assurance that, when the work is successful, the public is able to benefit from it eventually. The team that developed the one-hour Covid test found a potential commercial partner and so might well overcome the oversight hurdle, but it's been 14 months since they developed the test--and counting.

In short, without some kind of oversight mechanism for the work of independent biomedical researchers, the solutions they innovate will never have the opportunity to reach consumers.

In a new paper in the journal Citizen Science: Theory & Practice, we consider the issue of the ethics gap and ask whether ethics oversight is something nontraditional researchers want, and if so, what forms it might take. Given that individuals within these communities sometimes vehemently disagree with each other, is consensus on these questions even possible?

We learned that there is no "one size fits all" solution for ethics oversight of nontraditional research. Rather, the appropriateness of any oversight model will depend on each initiative's objectives, needs, risks, and constraints.

We also learned that nontraditional researchers are generally willing (and in some cases eager) to engage with traditional scientific, legal, and bioethics experts on ethics, safety, and related questions.

We suggest that these experts make themselves available to help nontraditional researchers build infrastructure for ethics self-governance and identify when it might be necessary to seek outside assistance.

Independent biomedical research has promise, but like any emerging science, it poses novel ethical questions and challenges. Existing research ethics and oversight frameworks may not be well-suited to answer them in every context, so we need to think outside the box about what we can create for the future. That process should begin by talking to independent biomedical researchers about their activities, priorities, and concerns with an eye to understanding how best to support them.

Christi Guerrini, JD, MPH studies biomedical citizen science and is an Associate Professor at Baylor College of Medicine. Alex Pearlman, MA, is a science journalist and bioethicist who writes about emerging issues in biotechnology. They have recently launched outlawbio.org, a place for discussion about nontraditional research.

Sept. 13th Event: Delta, Vaccines, and Breakthrough Infections

A visualization of the virus that causes COVID-19.

This virtual event will convene leading scientific and medical experts to address the public's questions and concerns about COVID-19 vaccines, Delta, and breakthrough infections. Audience Q&A will follow the panel discussion. Your questions can be submitted in advance at the registration link.

DATE:

Monday, September 13th, 2021

12:30 p.m. - 1:45 p.m. EDT

REGISTER:

Dr. Amesh Adalja, M.D., FIDSA, Senior Scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security; Adjunct Assistant Professor, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; Affiliate of the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health. His work is focused on emerging infectious disease, pandemic preparedness, and biosecurity.

Dr. Nahid Bhadelia, M.D., MALD, Founding Director, Boston University Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases Policy and Research (CEID); Associate Director, National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL), Boston University; Associate Professor, Section of Infectious Diseases, Boston University School of Medicine. She is an internationally recognized leader in highly communicable and emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) with clinical, field, academic, and policy experience in pandemic preparedness.

Dr. Akiko Iwasaki, Ph.D., Waldemar Von Zedtwitz Professor of Immunobiology and Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology and Professor of Epidemiology (Microbial Diseases), Yale School of Medicine; Investigator, Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Her laboratory researches how innate recognition of viral infections lead to the generation of adaptive immunity, and how adaptive immunity mediates protection against subsequent viral challenge.

Dr. Marion Pepper, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Department of Immunology, University of Washington. Her lab studies how cells of the adaptive immune system, called CD4+ T cells and B cells, form immunological memory by visualizing their differentiation, retention, and function.

Dr. Marion Pepper, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Department of Immunology, University of Washington. Her lab studies how cells of the adaptive immune system, called CD4+ T cells and B cells, form immunological memory by visualizing their differentiation, retention, and function.

This event is the third of a four-part series co-hosted by Leaps.org, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and the Sabin–Aspen Vaccine Science & Policy Group, with generous support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.