Scientists May Soon Be Able to Turn Off Pain with Gene Editing: Should They?

The CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing tool could be used to "turn off" pain directly, raising ethical questions for society.

Scientists have long been aware that some people live with what's known as "congenital insensitivity to pain"—the inability to register the tingles, jolts, and aches that alert most people to injury or illness.

"If you break the chain of transmission somewhere along there, it doesn't matter what the message is—the recipient will not get it."

On the ospposite end of the spectrum, others suffer from hyperalgesia, or extreme pain; for those with erythromelalgia, also known as "Man on Fire Syndrome," warm temperatures can feel like searing heat—even wearing socks and shoes can make walking unbearable.

Strangely enough, the two conditions can be traced to mutations in the same gene, SCN9A. It produces a protein that exists in spinal cells—specifically, in the dorsal root ganglion—which transmits the sensation of pain from the nerves at the peripheral site of an injury into the central nervous system and to the brain. This fact may become the key to pain relief for the roughly 20 percent of Americans who suffer from chronic pain, and countless other patients around the world.

"If you break the chain of transmission somewhere along there, it doesn't matter what the message is—the recipient will not get it," said Dr. Fyodor Urnov, director of the Innovative Genomics Institute and a professor of molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley. "For scientists and clinicians who study this, [there's] this consistent tracking of: You break this gene, you stop feeling pain; make this gene hyperactive, you feel lots of pain—that really cuts through the correlation versus causation question."

Researchers tried for years, without much success, to find a chemical that would block that protein from working and therefore mute the pain sensation. The CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing tool could completely sidestep that approach and "turn off" pain directly.

Yet as CRISPR makes such targeted therapies increasingly possible, the ethical questions surrounding gene editing have taken on a new and more urgent cast—particularly in light of the work of the disgraced Chinese scientist He Jiankui, who announced in late 2018 that he had created the world's first genetically edited babies. He used CRISPR to edit two embryos, with the goal of disabling a gene that makes people susceptible to HIV infection; but then took the unprecedented step of implanting the edited embryos for pregnancy and birth.

Edits to germline cells, like the ones He undertook, involve alterations to gametes or embryos and carry much higher risk than somatic cell edits, since changes will be passed on to any future generations. There are also concerns that imprecise edits could result in mutations and end up causing more disorders. Recent developments, particularly the "search-and replace" prime-editing technique published last fall, will help minimize those accidental edits, but the fact remains that we have little understanding of the long-term effects of these germline edits—for the future of the patients themselves, or for the broader gene pool.

"We need to have appropriate venues where we deliberate and consider the ethical, legal and social implications of gene editing as a society."

It is much harder to predict the effects, harmful or otherwise, on the larger human population as a result of interactions with the environment or other genetic variations; with somatic cell edits, on the other hand— like the ones that would be made in an individual to turn off pain—only the person receiving the treatment is affected.

Beyond the somatic/germline distinction, there is also a larger ethical question over how much genetic interference society is willing to tolerate, which may be couched as the difference between therapeutic editing—interventions in response to a demonstrated medical need—and "enhancement" editing. The Chinese scientist He was roundly criticized in the scientific community for the fact that there are already much safer and more proven methods of preventing the parent-to-child transmission of HIV through the IVF process, making his genetic edits medically unnecessary. (The edits may also have increased the girls' risk of susceptibility to other viruses, like influenza and the West Nile virus.)

Yet there are even more extreme goals that CRISPR could be used to reach, ones further removed from any sort of medical treatment. The 1997 science fiction movie Gattaca imagined a dystopian future where genetic selection for strength and intelligence is common, creating a society that explicitly and unapologetically endorses eugenics. In the real world, Russian President Vladimir Putin has commented that genetic editing could be used to create "a genius mathematician, a brilliant musician or a soldier, a man who can fight without fear, compassion, regret or pain."

"[Such uses] would be considered using gene editing for 'enhancement,'" said Dr. Zubin Master, an associate professor of biomedical ethics at the Mayo Clinic, who noted that a series of studies have strongly suggested that members of the public, in the U.S. and around the world, are much less amenable to the prospect of gene editing for these purposes than for the treatment of illness and disease.

Putin's comments were made in 2017, before news of He's experiment broke; since then no country has moved to continue experiments on germline editing (although one Russian IVF specialist, Denis Rebrikov, appears ready to do so, if given approval). Master noted that the World Health Organization has an 18-person committee currently dedicated to considering these questions. The Expert Advisory Committee on Developing Global Standards for Governance and Oversight of Human Genome Editing first convened in March 2019; that July, it issued a recommendation to regulatory and ethics authorities in all countries to refrain from approving clinical application requests for work on human germline genome editing—the kind of alterations to genetic cells used by He. The committee's report and a fleshed-out set of guidelines is expected after its final meeting, in Geneva this September (unless the COVID-19 pandemic disrupts the timeline).

Regardless of the WHO's report, in the U.S., all regulations of new medical procedures are overseen at the federal level, subjected to extensive regulatory review by the FDA; the chance of any doctor or company going rogue is minimal to none. Likewise, the challenges we face are more on the regulatory end of the spectrum than the Gattaca end. Dr. Stephanie Malia Fullerton, a bioethics professor at the University of Washington, pointed out that eugenics not only typically involves state-sponsored control of reproduction, but requires a much more clearly delineated genetic basis of common complex traits—indeed, SCN9A is one way to get to pain, but is not the only source—and suggested that current concerns about over-prescribing opioids are a more pressing question for society to address.

In fact, Navega Therapeutics, based in San Diego, hopes to find out whether the intersection of this research into SCN9A and CRISPR would be an effective way to address the U.S. opioid crisis. Currently in a preclinical funding stage, Navega's approach focuses on editing epigenetic molecules attached to the basic DNA strand—the idea is that the gene's expression can be activated or suppressed rather than removed entirely, reducing the risk of unwanted side effects from permanently altering the genetic code.

As these studies focused on the sensation of pain go forward, what we are likely to see simultaneously is the use of CRISPR to target diseases that are the root causes of that pain. Last summer, Victoria Gray, a Mississippi woman with sickle cell disease was the second-ever person to be treated with CRISPR therapy in the U.S. The disease is caused by a genetic mutation that creates malformed blood cells, which can't carry oxygen as normal and get stuck inside blood vessels, causing debilitating pain. For the study, conducted in concert with CRISPR Therapeutics, of Cambridge, Mass., cells were removed from Gray's bone marrow, modified using CRISPR, and infused back into her body, a technique called ex vivo editing.

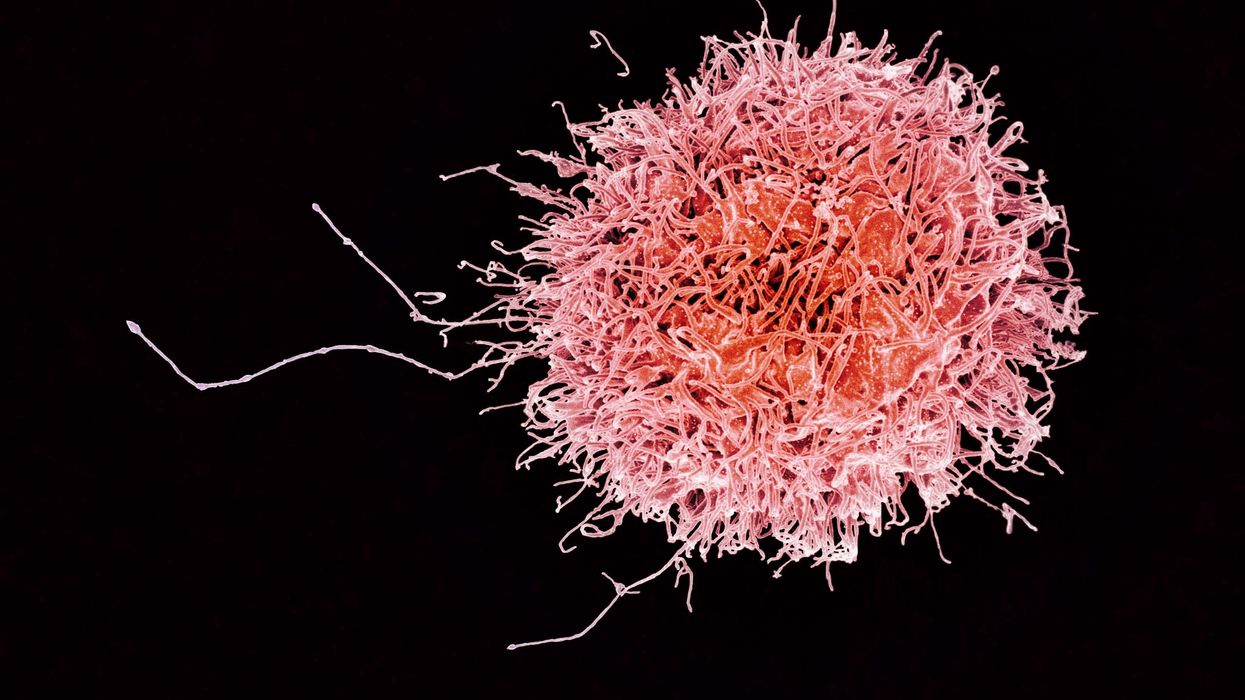

In early February this year, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania published a study on a first-in-human phase 1 clinical trial, in which three patients with advanced cancer received an infusion of ex vivo engineered T cells in an effort to improve antitumor immunity. The modified cells persisted for up to nine months, and the patients experienced no serious adverse side effects, suggesting that this sort of therapeutic gene editing can be performed safely and could potentially allow patients to avoid the excruciating process of chemotherapy.

Then, just this spring, researchers made another advance: The first attempt at in vivo CRISPR editing—where the edits happen inside the patient's body—is currently underway, as doctors attempt to treat a patient blinded by Leber congenital amaurosis, a rare genetic disorder. In an Oregon study sponsored by Editas Medicine and Allergan, the patient, a volunteer, was injected with a harmless virus carrying CRISPR gene-editing machinery; the hope is that the tool will be able to edit out the genetic defect and restore production of a crucial protein. Based on preliminary safety reports, the study has been cleared to continue, and data on higher doses may be available by the end of 2020. Editas Medicine and CRISPR Therapeutics are joined in this sphere by Intellia Therapeutics, which is seeking approval for a trial later this year on amyloidosis, a rare liver condition.

For any such treatment targeting SCN9A to make its way to human subjects, it would first need to undergo years' worth of testing—on mice, on primates, and then on volunteer patients after an extended informed-consent process. If everything went perfectly, Urnov estimates it could take at least three to four years end to end and cost between $5 and 10 million—but that "if" is huge.

"The idea of a regular human being, genetically pure of pain?"

And as that happens, "we need to have appropriate venues where we deliberate and consider the ethical, legal and social implications of gene editing as a society," Master said. CRISPR itself is open-source, but its application is subject to the approval of governments, institutions, and societies, which will need to figure out where to draw the line between miracle treatments and playing God. Something as unpleasant and ubiquitous as pain may in fact be the most appropriate place to start.

"The pain circuit is very old," Urnov said. "We have evolved with the senses that we have, and have become the species that we are, as a result of who we are, physiologically. Yes, I take Advil—but when I get a headache! The idea of a regular human being, genetically pure of pain?... The permanent disabling or turning down of the pain sensation, for anything other than a medical reason? … That seems to be challenging Mother Nature in the wrong ways."

Dr. May Edward Chinn, Kizzmekia Corbett, PhD., and Alice Ball, among others, have been behind some of the most important scientific work of the last century.

If you look back on the last century of scientific achievements, you might notice that most of the scientists we celebrate are overwhelmingly white, while scientists of color take a backseat. Since the Nobel Prize was introduced in 1901, for example, no black scientists have landed this prestigious award.

The work of black women scientists has gone unrecognized in particular. Their work uncredited and often stolen, black women have nevertheless contributed to some of the most important advancements of the last 100 years, from the polio vaccine to GPS.

Here are five black women who have changed science forever.

Dr. May Edward Chinn

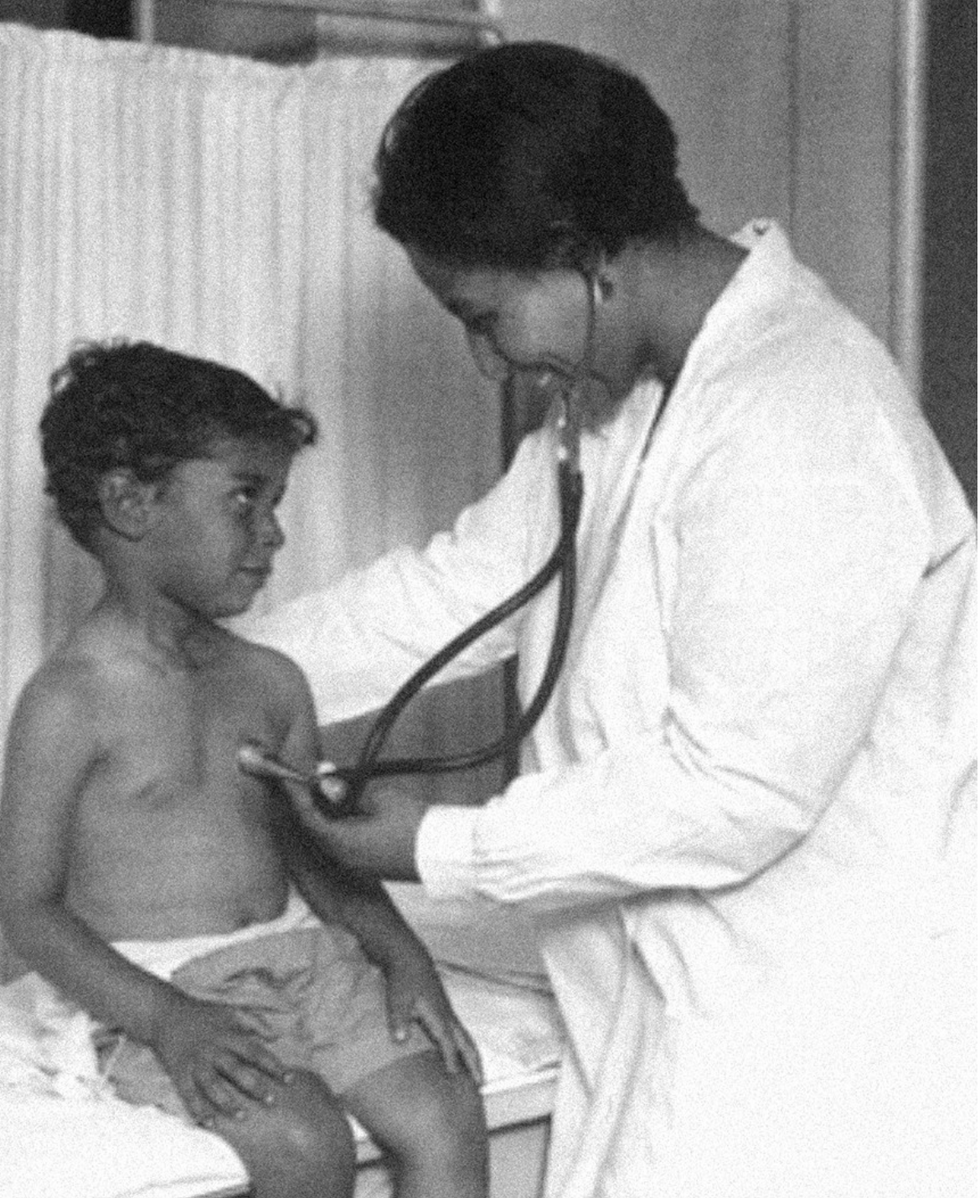

Dr. May Edward Chinn practicing medicine in Harlem

George B. Davis, PhD.

Chinn was born to poor parents in New York City just before the start of the 20th century. Although she showed great promise as a pianist, playing with the legendary musician Paul Robeson throughout the 1920s, she decided to study medicine instead. Chinn, like other black doctors of the time, were barred from studying or practicing in New York hospitals. So Chinn formed a private practice and made house calls, sometimes operating in patients’ living rooms, using an ironing board as a makeshift operating table.

Chinn worked among the city’s poor, and in doing this, started to notice her patients had late-stage cancers that often had gone undetected or untreated for years. To learn more about cancer and its prevention, Chinn begged information off white doctors who were willing to share with her, and even accompanied her patients to other clinic appointments in the city, claiming to be the family physician. Chinn took this information and integrated it into her own practice, creating guidelines for early cancer detection that were revolutionary at the time—for instance, checking patient health histories, checking family histories, performing routine pap smears, and screening patients for cancer even before they showed symptoms. For years, Chinn was the only black female doctor working in Harlem, and she continued to work closely with the poor and advocate for early cancer screenings until she retired at age 81.

Alice Ball

Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

Alice Ball was a chemist best known for her groundbreaking work on the development of the “Ball Method,” the first successful treatment for those suffering from leprosy during the early 20th century.

In 1916, while she was an undergraduate student at the University of Hawaii, Ball studied the effects of Chaulmoogra oil in treating leprosy. This oil was a well-established therapy in Asian countries, but it had such a foul taste and led to such unpleasant side effects that many patients refused to take it.

So Ball developed a method to isolate and extract the active compounds from Chaulmoogra oil to create an injectable medicine. This marked a significant breakthrough in leprosy treatment and became the standard of care for several decades afterward.

Unfortunately, Ball died before she could publish her results, and credit for this discovery was given to another scientist. One of her colleagues, however, was able to properly credit her in a publication in 1922.

Henrietta Lacks

onathan Newton/The Washington Post/Getty

The person who arguably contributed the most to scientific research in the last century, surprisingly, wasn’t even a scientist. Henrietta Lacks was a tobacco farmer and mother of five children who lived in Maryland during the 1940s. In 1951, Lacks visited Johns Hopkins Hospital where doctors found a cancerous tumor on her cervix. Before treating the tumor, the doctor who examined Lacks clipped two small samples of tissue from Lacks’ cervix without her knowledge or consent—something unthinkable today thanks to informed consent practices, but commonplace back then.

As Lacks underwent treatment for her cancer, her tissue samples made their way to the desk of George Otto Gey, a cancer researcher at Johns Hopkins. He noticed that unlike the other cell cultures that came into his lab, Lacks’ cells grew and multiplied instead of dying out. Lacks’ cells were “immortal,” meaning that because of a genetic defect, they were able to reproduce indefinitely as long as certain conditions were kept stable inside the lab.

Gey started shipping Lacks’ cells to other researchers across the globe, and scientists were thrilled to have an unlimited amount of sturdy human cells with which to experiment. Long after Lacks died of cervical cancer in 1951, her cells continued to multiply and scientists continued to use them to develop cancer treatments, to learn more about HIV/AIDS, to pioneer fertility treatments like in vitro fertilization, and to develop the polio vaccine. To this day, Lacks’ cells have saved an estimated 10 million lives, and her family is beginning to get the compensation and recognition that Henrietta deserved.

Dr. Gladys West

Andre West

Gladys West was a mathematician who helped invent something nearly everyone uses today. West started her career in the 1950s at the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division in Virginia, and took data from satellites to create a mathematical model of the Earth’s shape and gravitational field. This important work would lay the groundwork for the technology that would later become the Global Positioning System, or GPS. West’s work was not widely recognized until she was honored by the US Air Force in 2018.

Dr. Kizzmekia "Kizzy" Corbett

TIME Magazine

At just 35 years old, immunologist Kizzmekia “Kizzy” Corbett has already made history. A viral immunologist by training, Corbett studied coronaviruses at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and researched possible vaccines for coronaviruses such as SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome).

At the start of the COVID pandemic, Corbett and her team at the NIH partnered with pharmaceutical giant Moderna to develop an mRNA-based vaccine against the virus. Corbett’s previous work with mRNA and coronaviruses was vital in developing the vaccine, which became one of the first to be authorized for emergency use in the United States. The vaccine, along with others, is responsible for saving an estimated 14 million lives.On today’s episode of Making Sense of Science, I’m honored to be joined by Dr. Paul Song, a physician, oncologist, progressive activist and biotech chief medical officer. Through his company, NKGen Biotech, Dr. Song is leveraging the power of patients’ own immune systems by supercharging the body’s natural killer cells to make new treatments for Alzheimer’s and cancer.

Whereas other treatments for Alzheimer’s focus directly on reducing the build-up of proteins in the brain such as amyloid and tau in patients will mild cognitive impairment, NKGen is seeking to help patients that much of the rest of the medical community has written off as hopeless cases, those with late stage Alzheimer’s. And in small studies, NKGen has shown remarkable results, even improvement in the symptoms of people with these very progressed forms of Alzheimer’s, above and beyond slowing down the disease.

In the realm of cancer, Dr. Song is similarly setting his sights on another group of patients for whom treatment options are few and far between: people with solid tumors. Whereas some gradual progress has been made in treating blood cancers such as certain leukemias in past few decades, solid tumors have been even more of a challenge. But Dr. Song’s approach of using natural killer cells to treat solid tumors is promising. You may have heard of CAR-T, which uses genetic engineering to introduce cells into the body that have a particular function to help treat a disease. NKGen focuses on other means to enhance the 40 plus receptors of natural killer cells, making them more receptive and sensitive to picking out cancer cells.

Paul Y. Song, MD is currently CEO and Vice Chairman of NKGen Biotech. Dr. Song’s last clinical role was Asst. Professor at the Samuel Oschin Cancer Center at Cedars Sinai Medical Center.

Dr. Song served as the very first visiting fellow on healthcare policy in the California Department of Insurance in 2013. He is currently on the advisory board of the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago and a board member of Mercy Corps, The Center for Health and Democracy, and Gideon’s Promise.

Dr. Song graduated with honors from the University of Chicago and received his MD from George Washington University. He completed his residency in radiation oncology at the University of Chicago where he served as Chief Resident and did a brachytherapy fellowship at the Institute Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France. He was also awarded an ASTRO research fellowship in 1995 for his research in radiation inducible gene therapy.

With Dr. Song’s leadership, NKGen Biotech’s work on natural killer cells represents cutting-edge science leading to key findings and important pieces of the puzzle for treating two of humanity’s most intractable diseases.

Show links

- Paul Song LinkedIn

- NKGen Biotech on Twitter - @NKGenBiotech

- NKGen Website: https://nkgenbiotech.com/

- NKGen appoints Paul Song

- Patient Story: https://pix11.com/news/local-news/long-island/promising-new-treatment-for-advanced-alzheimers-patients/

- FDA Clearance: https://nkgenbiotech.com/nkgen-biotech-receives-ind-clearance-from-fda-for-snk02-allogeneic-natural-killer-cell-therapy-for-solid-tumors/Q3 earnings data: https://www.nasdaq.com/press-release/nkgen-biotech-inc.-reports-third-quarter-2023-financial-results-and-business