SCOOP: Largest Cryobank in the U.S. to Offer Ancestry Testing

Vanessa Colimorio (left) and Sharon Kochlany (right) at a farm with their four-year-old twin daughters and one-year-old son. The kids share the same sperm donor.

Sharon Kochlany and Vanessa Colimorio's four-year-old twin girls had a classic school assignment recently: make a family tree. They drew themselves and their one-year-old brother branching off from their moms, with aunts, uncles, and grandparents forking off to the sides.

The recently-gained sovereignty of queer families stands to be lost if a consumer DNA test brings a stranger's identity out of the woodwork.

What you don't see in the invisible space between Kochlany and Colimorio, however, is the sperm donor they used to conceive all three children.

To look at a family tree like this is to see in its purest form that kinship can supersede biology—the boundaries of where this family starts and stops are clear to everyone in it, in spite of a third party's genetic involvement. This kind of self-definition has always been synonymous with LGBTQ families, especially those that rely on donor gametes (sperm or eggs) to exist.

But the world around them has changed quite suddenly: The recent consumer DNA testing boom has made it more complicated than ever for families built through reproductive technology—openly, not secretively—to maintain the strong sense of autonomy and privacy that can be crucial for their emotional security. Prospective parents and cryobanks are now mulling how best to bring a new generation of donor-conceived people into this world in a way that leaves open the choice to know more about their ancestry without obliterating an equally important choice: the right not to know about biological relatives.

For queer parents who have long fought for social acceptance, having a biological relationship to their children has been revolutionary, and using an unknown donor as a means to this end especially so. Getting help from a friend often comes with the expectation that the friend will also have social involvement in the family, which some people are comfortable with, but being able to access sperm from an unknown donor—which queer parents have only been able to openly do since the early 1980s—grants them the reproductive autonomy to create families seemingly on their own. That recently-gained sovereignty stands to be lost if a consumer DNA test brings a stranger's identity out of the woodwork.

At the same time, it's natural for donor-conceived people to want to know more about where they come from ethnically, even if they don't want to know the identity of their donor. As a donor-conceived person myself, I know my donor's self-reported ethnicity, but have often wondered how accurate it is.

Opening the Pandora's box of a consumer DNA test as a way to find out has always felt profoundly unappealing to me, however. Many people have accidentally learned they're donor-conceived by unwittingly using these tools, but I already know that about myself going in, and subsequently know I'll be connected to a large web of people whose existence I'm not interested in learning about. In addition to possibly identifying my anonymous donor, his family could also show up, along with any donor-siblings—other people with whom I share a donor. My single lesbian mom is enough for me, and the trade off to learn more about my ethnic ancestry has never seemed worth it.

In 1992, when I was born, no one was planning for how consumer DNA tests might upend or illuminate one's sense of self. But the donor community has always had to stay nimble with balancing privacy concerns and psychological well-being, so it should come as no surprise that figuring out how to do so in 2020 includes finding a way to offer ancestry insight while circumventing consumer DNA tests.

A New Paradigm

This is the rationale behind unprecedented industry news that LeapsMag can exclusively break: Within the next few weeks, California Cryobank, the largest cryobank in the country, will begin offering genetically-verified ancestry information on the free public part of every donor's anonymous profile in its database, something no other cryobanks yet offer (an exact launch date was not available at the time of publication). Currently, California Cryobank's donor profiles include a short self-reported list that might merely say, "Ancestry: German, Lebanese, Scottish."

The new information will be a report in pie chart form that details exactly what percentages of a donor's DNA come from up to 26 ethnicities—it's analogous to, but on a smaller scale than, the format offered by consumer DNA testing companies, and uses the same base technology that looks for single nucleotide polymorphisms in DNA that are associated with specific ethnicities. But crucially, because the donor takes the DNA test through California Cryobank, not a consumer-facing service, the information is not connected in a network to anyone else's DNA test. It's also taken before any offspring exist so there's no chance of revealing a donor-conceived person's identity this way.

Later, when a donor-conceived person is born, grows up, and wants information about their ethnicity from the donor side, all they need is their donor's anonymous ID number to look it up. The donor-conceived person never takes a genetic test, and therefore also can't accidentally find donor siblings this way. People who want to be connected to donor siblings can use a sibling registry where other people who want to be found share donor ID numbers and look for matches (this is something that's been available for decades, and remains so).

"With genetic testing, you have no control over who reaches out to you, and at what point in your life."

California Cryobank will require all new donors to consent to this extra level of genetic testing, setting a new standard for what information prospective parents and donor-conceived people can expect to have. In the immediate, this information will be most useful for prospective parents looking for donors with specific backgrounds, possibly ones similar to their own.

It's a solution that was actually hiding in plain sight. Two years ago, California Cryobank's partner Sema4, the company handling the genetic carrier testing that's used to screen for heritable diseases, started analyzing ethnic data in its samples. That extra information was being collected because it can help calculate a more accurate assessment of genetic risks that run in certain populations—like Ashkenazi Jews and Tay Sachs disease—than relying on oral family histories. Shortly after a plan to start collecting these extra data, Jamie Shamonki, chief medical officer of California Cryobank, realized the companies would be sitting on a goldmine for a different reason.

"I didn't want to use one of these genetic testing companies like Ancestry to accomplish this," says Shamonki. "The whole thing we're trying to accomplish is also privacy."

Consumer-facing DNA testing companies are not HIPAA compliant (whereas Sema4, which isn't direct-to-consumer, is HIPAA compliant), which means there are no legal privacy protections covering people who add their DNA to these databases. Although some companies, like 23andMe, allow users to opt-out of being connected with genetic relatives, the language can be confusing to navigate, requires a high level of knowledge and self-advocacy on the user's part, and, as an opt-out system, is not set up to protect the user from unwanted information by default; many unwittingly walk right into such information as a result.

Additionally, because consumer-facing DNA testing companies operate outside the legal purview that applies to other health care entities, like hospitals, even a person who does opt-out of being linked to genetic relatives is not protected in perpetuity from being re-identified in the future by a change in company policy. The safest option for people with privacy concerns is to stay out of these databases altogether.

For California Cryobank, the new information about donor heritage won't retroactively be added to older profiles in the system, so donor-conceived people who already exist won't benefit from the ancestry tool, but it'll be the new standard going forward. The company has about 500 available donors right now, many of which have been in their registry for a while; about 100 of those donors, all new, will have this ancestry data on their profiles.

Shamonki says it has taken about two years to get to the point of publicly including ancestry information on a donor's profile because it takes about nine months of medical and psychological screening for a donor to go from walking through the door to being added to their registry. The company wanted to wait to launch until it could offer this information for a significant number of donors. As more new donors come online under the new protocol, the number with ancestry information on their profiles will go up.

For Parents: An Unexpected Complication

While this change will no doubt be welcome progress for LGBTQ families contemplating parenthood, it'll never be possible to put this entire new order back in the box. What are such families who already have donor-conceived children losing in today's world of widespread consumer genetic testing?

Kochlany and Colimorio's twins aren't themselves much older than the moment at-home DNA testing really started to take off. They were born in 2015, and two years later the industry saw its most significant spike. By now, more than 26 million people's DNA is in databases like 23andMe and Ancestry; as a result, it's estimated that within a year, 90 percent of Americans of European descent will be identifiable through these consumer databases, by way of genetic third cousins, even if they didn't want to be found and never took the test themselves. This was the principle behind solving the Golden State Killer cold case.

The waning of privacy through consumer DNA testing fundamentally clashes with the priorities of the cyrobank industry, which has long sought to protect the privacy of donor-conceived people, even as open identification became standard. Since the 1980s, donors have been able to allow their identity to be released to any offspring who is at least 18 and wants the information. Lesbian moms pushed for this option early on so their children—who would obviously know they couldn't possibly be the biological product of both parents—would never feel cut off from the chance to know more about themselves. But importantly, the openness is not a two-way street: the donors can't ever ask for the identities of their offspring. It's the latter that consumer DNA testing really puts at stake.

"23andMe basically created the possibility that there will be donors who will have contact with their donor-conceived children, and that's not something that I think the donor community is comfortable with," says I. Glenn Cohen, director of Harvard Law School's Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology & Bioethics. "That's about the donor's autonomy, not the rearing parents' autonomy, or the donor-conceived child's autonomy."

Kochlany and Colimorio have an open identification donor and fully support their children reaching out to California Cryobank to get more information about him if they want to when they're 18, but having a singular name revealed isn't the same thing as having contact, nor is it the same thing as revealing a web of dozens of extended genetic relations. Their concern now is that if their kids participate in genetic testing, a stranger—someone they're careful to refer to as only "the donor" and never "dad"—will reach out to the children to begin some kind of relationship. They know other people who are contemplating giving their children DNA tests, and feel staunchly that it wouldn't be right for their family.

"With genetic testing, you have no control over who reaches out to you, and at what point in your life," Kochlany says. "[People] reaching out and trying to say, 'Hey I know who your dad is' throws a curveball. It's like, 'Wait, I never thought I had a dad.' It might put insecurities in their minds."

"We want them to have the opportunity to choose whether or not they want to reach out," Colimorio adds.

Kochlany says that when their twins are old enough to start asking questions, she and Colimorio plan to frame it like this: "The donor was kind of like a technology that helped us make you a person, and make sure that you exist," she says, role playing a conversation with their kids. "But it's not necessarily that you're looking to this person [for] support or love, or because you're missing a piece."

It's a line in the sand that's present even for couples still far off from conceiving. When Mallory Schwartz, a film and TV producer in Los Angeles, and Lauren Pietra, a marriage and family therapy associate (and Shamonki's step-daughter), talk about getting married someday, it's a package deal with talking about how they'll approach having kids. They feel there are too many variables and choices to make around family planning as a same-sex couple these days to not have those conversations simultaneously. Consumer DNA databases are already on their minds.

"It frustrates me that the DNA databases are just totally unregulated," says Schwartz. "I hope they are by the time we do this. I think everyone deserves a right to privacy when making your family [using a sperm donor]."

"I wouldn't want to create a world where people who are donor-conceived feel like they can't participate in this technology because they're trying to shut out [other] information."

On the prospect of having a donor relation pop up non-consensually for a future child, Pietra says, "I don't like it. It would be really disappointing if the child didn't want [contact], and unfortunately they're on the receiving end."

You can see how important preserving the right to keep this door closed is when you look at what's going on at The Sperm Bank of California. This pioneering cryobank was the first in the world to openly serve LGBTQ people and single women, and also the first to offer the open identification option when it opened in 1982, but not as many people are asking for their donor's identity as expected.

"We're finding a third of young people are coming forward for their donor's identity," says Alice Ruby, executive director. "We thought it would be a higher number." Viewed the other way, two-thirds of the donor-conceived people who could ethically get their donor's identity through The Sperm Bank of California are not asking the cryobank for it.

Ruby says that part of what historically made an open identification program appealing, rather than invasive or nerve-wracking, is how rigidly it's always been formatted around mutual consent, and protects against surprises for all parties. Those [donor-conceived people] who wanted more information were never barred from it, while those who wanted to remain in the dark could. No one group's wish eclipsed the other's. The potential breakdown of a system built around consent, expectations, and respect for privacy is why unregulated consumer DNA testing is most concerning to her as a path for connecting with genetic relatives.

For the last few decades in cryobanks around the world, the largest cohort of people seeking out donor sperm has been lesbian couples, followed by single women. For infertile heterosexual couples, the smallest client demographic, Ruby says donor sperm offers a solution to a medical problem, but in contrast, it historically "provided the ability for [lesbian] couples and single moms to have some reproductive autonomy." Yes, it was still a solution to a biological problem, but it was also a solution to a social one.

The Sperm Bank of California updated its registration forms to include language urging parents, donor-conceived people, and donors not to use consumer DNA tests, and to go through the cryobank if they, understandably, want to learn more about who they're connected to. But truthfully, there's not much else cryobanks can do to protect clients on any side of the donor transaction from surprise contact right now—especially not from relatives of the donor who may not even know someone in their family has donated sperm.

A Tricky Position

Personally, I've known I was donor-conceived from day one. It has never been a source of confusion, angst, or curiosity, and in fact has never loomed particularly large for me in any way. I see it merely as a type of reproductive technology—on par with in vitro fertilization—that enabled me to exist, and, now that I do exist, is irrelevant. Being confronted with my donor's identity or any donor siblings would make this fact of my conception bigger than I need it to be, as an adult with a full-blown identity derived from all of my other life experiences. But I still wonder about the minutiae of my ethnicity in much the same way as anyone else who wonders, and feel there's no safe way for me to find out without relinquishing some of my existential independence.

"People obviously want to participate in 23andMe and Ancestry because they're interested in knowing more about themselves," says Shamonki. "I wouldn't want to create a world where people who are donor-conceived feel like they can't participate in this technology because they're trying to shut out [other] information."

After all, it was the allure of that exact conceit—knowing more about oneself—that seemed to magnetically draw in millions of people to these tools in the first place. It's an experience that clearly taps into a population-wide psychic need, even—perhaps especially—if one's origins are a mystery.

Want to Motivate Vaccinations? Message Optimism, Not Doom

There is a lot to be optimistic about regarding the new safe and highly effective vaccines, which are moving society closer toward the goal of close human contact once again.

After COVID-19 was declared a worldwide pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, life as we knew it altered dramatically and millions went into lockdown. Since then, most of the world has had to contend with masks, distancing, ventilation and cycles of lockdowns as surges flare up. Deaths from COVID-19 infection, along with economic and mental health effects from the shutdowns, have been devastating. The need for an ultimate solution -- safe and effective vaccines -- has been paramount.

On November 9, 2020 (just 8 months after the pandemic announcement), the press release for the first effective COVID-19 vaccine from Pfizer/BioNTech was issued, followed by positive announcements regarding the safety and efficacy of five other vaccines from Moderna, University of Oxford/AztraZeneca, Novavax, Johnson and Johnson and Sputnik V. The Moderna and Pfizer vaccines have earned emergency use authorization through the FDA in the United States and are being distributed. We -- after many long months -- are seeing control of the devastating COVID-19 pandemic glimmering into sight.

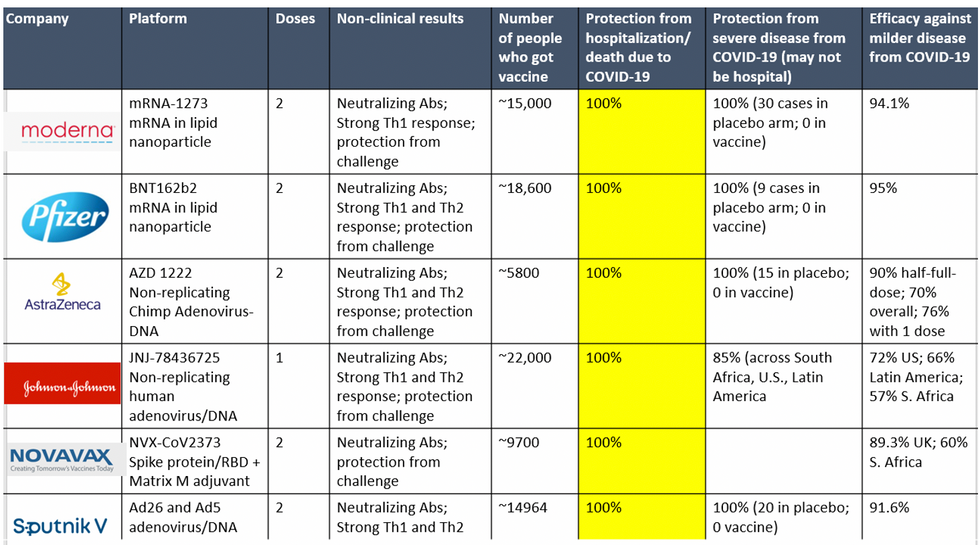

To be clear, these vaccine candidates for COVID-19, both authorized and not yet authorized, are highly effective and safe. In fact, across all trials and sites, all six vaccines were 100% effective in preventing hospitalizations and death from COVID-19.

All Vaccines' Phase 3 Clinical Data

Complete protection against hospitalization and death from COVID-19 exhibited by all vaccines with phase 3 clinical trial data.

This astounding level of protection from SARS-CoV-2 from all vaccine candidates across multiple regions is likely due to robust T cell response from vaccination and will "defang" the virus from the concerns that led to COVID-19 restrictions initially: the ability of the virus to cause severe illness. This is a time of hope and optimism. After the devastating third surge of COVID-19 infections and deaths over the winter, we finally have an opportunity to stem the crisis – if only people readily accept the vaccines.

Amidst these incredible scientific advancements, however, public health officials and politicians have been pushing downright discouraging messaging. The ubiquitous talk of ongoing masks and distancing restrictions without any clear end in sight threatens to dampen uptake of the vaccines. It's imperative that we break down each concern and see if we can revitalize our public health messaging accordingly.

The first concern: we currently do not know if the vaccines block asymptomatic infection as well as symptomatic disease, since none of the phase 3 vaccine trials were set up to answer this question. However, there is biological plausibility that the antibodies and T-cell responses blocking symptomatic disease will also block asymptomatic infection in the nasal passages. IgG immunoglobulins (generated and measured by the vaccine trials) enter the nasal mucosa and systemic vaccinations generate IgA antibodies at mucosal surfaces. Monoclonal antibodies given to outpatients with COVID-19 hasten viral clearance from the airways.

Although it is prudent for those who are vaccinated to wear masks around the unvaccinated in case a slight risk of transmission remains, two fully vaccinated people can comfortably abandon masking around each other.

Moreover, data from the AztraZeneca trial (including in the phase 3 trial final results manuscript), where weekly self-swabbing was done by participants, and data from the Moderna trial, where a nasal swab was performed prior to the second dose, both showed risk reductions in asymptomatic infection with even a single dose. Finally, real-world data from a large Pfizer-based vaccine campaign in Israel shows a 50% reduction in infections (asymptomatic or symptomatic) after just the first dose.

Therefore, the likelihood of these vaccines blocking asymptomatic carriage, as well as symptomatic disease, is high. Although it is prudent for those who are vaccinated to wear masks around the unvaccinated in case a slight risk of transmission remains, two fully vaccinated people can comfortably abandon masking around each other. Moreover, as the percentage of vaccinated people increases, it will be increasingly untenable to impose restrictions on this group. Once herd immunity is reached, these restrictions can and should be abandoned altogether.

The second concern translating to "doom and gloom" messaging lately is around the identification of troubling new variants due to enhanced surveillance via viral sequencing. Four major variants circulating at this point (with others described in the past) are the B.1.1.7 variant ("UK variant"), B.1.351 ("South Africa variant), P.1. ("Brazil variant"), and the L452R variant identified in California. Although the UK variant is likely to be more transmissible, as is the South Africa variant, we have no reason to believe that masks, distancing and ventilation are ineffective against these variants.

Moreover, neutralizing antibody titers with the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines do not seem to be significantly reduced against the variants. Finally, although the Novavax 2-dose and Johnson and Johnson (J&J) 1-dose vaccines had lower rates of efficacy against moderate COVID-19 disease in South Africa, their efficacy against severe disease was impressively high. In fact J&J's vaccine still prevented 100% of hospitalizations and death from COVID-19. When combining both hospitalizations/deaths and severe symptoms managed at home, the J&J 1-dose vaccine was 85% protective across all three sites of the trial: the U.S., Latin America (including Brazil), and South Africa.

In South Africa, nearly all cases of COVID-19 (95%) were due to infection with the B.1.351 SARS-CoV-2 variant. Finally, since herd immunity does not rely on maximal immune responses among all individuals in a society, the Moderna/Pfizer/J&J vaccines are all likely to achieve that goal against variants. And thankfully, all of these vaccines can be easily modified to boost specifically against a new variant if needed (indeed, Moderna and Pfizer are already working on boosters against the prominent variants).

The third concern of some public health officials is that people will abandon all restrictions once vaccinated unless overly cautious messages are drilled into them. Indeed, the false idea that if you "give people an inch, they will take a mile" has been misinforming our messaging about mitigation since the beginning of the pandemic. For example, the very phrase "stay at home" with all of its non-applicability for essential workers and single individuals is stigmatizing and unrealistic for many. Instead, the message should have focused on how people can additively reduce their risks under different circumstances.

The public will be more inclined to trust health officials if those officials communicate with nuanced messages backed up by evidence, rather than with broad brushstrokes that shame. Therefore, we should be saying that "vaccinated people can be together with other vaccinated individuals without restrictions but must protect the unvaccinated with masks and distancing." And we can say "unvaccinated individuals should adhere to all current restrictions until vaccinated" without fear of misunderstandings. Indeed, this kind of layered advice has been communicated to people living with HIV and those without HIV for a long time (if you have HIV but partner does not, take these precautions; if both have HIV, you can do this, etc.).

Our heady progress in vaccine development, along with the incredible efficacy results of all of them, is unprecedented. However, we are at risk of undermining such progress if people balk at the vaccine because they don't believe it will make enough of a difference. One of the most critical messages we can deliver right now is that these vaccines will eventually free us from the restrictions of this pandemic. Let's use tiered messaging and clear communication to boost vaccine optimism and uptake, and get us to the goal of close human contact once again.

Inside Scoop: How a DARPA Scientist Helped Usher in a Game-Changing Covid Treatment

Amy Jenkins is a program manager for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency's Biological Technologies Office, which runs a project called the Pandemic Prevention Platform.

Amy Jenkins was in her office at DARPA, a research and development agency within the Department of Defense, when she first heard about a respiratory illness plaguing the Chinese city of Wuhan. Because she's a program manager for DARPA's Biological Technologies Office, her colleagues started stopping by. "It's really unusual, isn't it?" they would say.

At the time, China had a few dozen cases of what we now call COVID-19. "We should maybe keep an eye on that," she thought.

Early in 2020, still just keeping watch, she was visiting researchers working on DARPA's Pandemic Prevention Platform (P3), a project to develop treatments for "any known or previously unknown infectious threat," within 60 days of its appearance. "We looked at each other and said, 'Should we be doing something?'" she says.

For projects like P3, groups of scientists—often at universities and private companies—compete for DARPA contracts, and program managers like Jenkins oversee the work. Those that won the P3 bid included scientists at AbCellera Biologics, Inc., AstraZeneca, Duke University, and Vanderbilt University.

At the time Jenkins was talking to the P3 performers, though, they didn't have evidence of community transmission. "We would have to cross that bar before we considered doing anything," she says.

The world soon leapt far over that bar. By the time Jenkins and her team decided P3 should be doing something—with their real work beginning in late February--it was too late to prevent this pandemic. But she could help P3 dig into the chemical foundations of COVID-19's malfeasance, and cut off its roots. That work represents, in fact, her roots.

In late February 2020, DARPA received a single blood sample from a recovered COVID-19 patient, in which P3 researchers could go fishing for antibodies. The day it arrived, Jenkins's stomach roiled. "We get one shot," she thought.

Fighting the Smallest Enemies

Jenkins, who's in her early 40s, first got into germs the way many 90s kids did: by reading The Hot Zone, a novel about a hemorrhagic fever gone rogue. It wasn't exactly the disintegrating organs that hooked her. It was the idea that "these very pathogens that we can't even see can make us so sick and bring us to our knees," she says. Reading about scientists facing down deadly disease, she wondered, "How do these things make you so sick?"

She chased that question in college, majoring in both biomolecular science and chemistry, and later became an antibody expert. Antibodies are proteins that hook to a pathogen to block it from attaching to your cells, or tag it for destruction by the rest of the immune system. Soon, she jumped on the "monoclonal antibodies" train—developing synthetic versions of these natural defenses, which doctors can give to people to help them battle an early-stage infection, and even to prevent an infection from taking root after an exposure.

Jenkins likens the antibody treatments to the old aphorism about fishing: Vaccines teach your body how to fish, but antibodies simply give your body the pesca-fare. While that, as the saying goes, won't feed you for a lifetime, it will last a few weeks or months. Monoclonal antibodies thus are a promising preventative option in the immediate short-term when a vaccine hasn't yet been given (or hasn't had time to produce an immune response), as well as an important treatment weapon in the current fight. After former president Donald Trump contracted COVID-19, he received a monoclonal antibody treatment from biotech company Regeneron.

As for Jenkins, she started working as a DARPA Biological Technologies Office contractor soon after completing her postdoc. But it was a suit job, not a labcoat job. And suit jobs, at first, left Jenkins conflicted, worried about being bored. She'd give it a year, she thought. But the year expired, and bored she was not. Around five years later, in June 2019, the agency hired her to manage several of the office's programs. A year into that gig, the world was months into a pandemic.

The Pandemic Pivot

At DARPA, Jenkins inherited five programs, including P3. P3 works by taking blood from recovered people, fishing out their antibodies, identifying the most effective ones, and then figuring out how to manufacture them fast. Back then, P3 existed to help with nebulous, future outbreaks: Pandemic X. Not this pandemic. "I did not have a crystal ball," she says, "but I will say that all of us in the infectious diseases and public-health realm knew that the next pandemic was coming."

Three days after a January 2020 meeting with P3 researchers, COVID-19 appeared in Seattle, then began whipping through communities. The time had come for P3 teams to swivel. "We had done this," she says. "We had practiced this before." But would their methods stand up to something unknown, racing through the global population? "The big anxiety was, 'Wow, this was real,'" says Jenkins.

While facing down that realness, Jenkins was also managing other projects. In one called PREPARE, groups develop "medical countermeasures" that modulate a person's genetic code to boost their bodies' responses to threats. Another project, NOW, envisions shipping-container-sized factories that can make thousands of vaccine doses in days. And then there's Prometheus—which means "forethought" in Greek, and is the name of the god who stole fire and gave it to humans. Wrapping up as COVID ramped up, Prometheus aimed to identify people who are contagious—with whatever—before they start coughing, and even if they never do.

All of DARPA's projects focus on developing early-stage technology, passing it off to other agencies or industry to put it into operation. The orientation toward a specific goal appealed to Jenkins, as a contrast to academia. "You go down a rabbit hole for years at a time sometimes, chasing some concept you found interesting in the lab," she says. That's good for the human pursuit of knowledge, and leads to later applications, but DARPA wants a practical prototype—stat.

"Dual-Use" Technologies

That desire, though, and the fact that DARPA is a defense agency, present philosophical complications. "Bioethics in the national-security context turns all the dials up to 10+," says Jonathan Moreno, a medical ethicist at the University of Pennsylvania.

While developing antibody treatments to stem a pandemic seems straightforwardly good, all biological research—especially that backed by military money—requires evaluating potential knock-on applications, even those that might come from outside the entity that did the developing. As Moreno put it, "Albert Einstein wasn't thinking about blowing up Hiroshima." Particularly sensitive are so-called "dual-use" technologies—those tools that could be used for both benign and nefarious purposes, or are of interest to both the civilian and military worlds.

Moreno takes Prometheus itself as an example of "dual-use" technology. "Think about somebody wearing a suicide vest. Instead of a suicide vest, make them extremely contagious with something. The flu plus Ebola," he says. "Send them someplace, a sensitive environment. We would like to be able to defend against that"—not just tell whether Uncle Fred is bringing asymptomatic COVID home for Christmas. Prometheus, Jenkins says, had safety in mind from the get-go, and required contenders to "develop a risk mitigation plan" and "detail their strategy for appropriate control of information."

To look at a different program, if you can modulate genes to help healing, you probably know something (or know someone else could infer something) about how to hinder healing. Those sorts of risks are why PREPARE researchers got their own "ethical, legal, and social implications" panel, which meets quarterly "to ensure that we are performing all research and publications in a safe and ethical manner," says Jenkins.

DARPA as a whole, Moreno says, is institutionally sensitive to bioethics. The agency has ethics panels, and funded a 2014 National Academies assessment of how to address the "ethical, legal, and societal issues" around technology that has military relevance. "In the cases of biotechnologies where some of that research brushes up against what could legitimately be considered dual-use, that in itself justifies our investment," says Jenkins. "DARPA deliberately focuses on safety and countermeasures against potentially dangerous technologies, and we structure our programs to be transparent, safe, and legal."

Going Fishing

In late February 2020, DARPA received a single blood sample from a recovered COVID-19 patient, in which P3 researchers could go fishing for antibodies. The day it arrived, Jenkins's stomach roiled. "We get one shot," she thought.

As scientists from the P3-funded AbCellera went through the processes they'd practiced, Jenkins managed their work, tracking progress and relaying results. Soon, the team had isolated a suitable protein: bamlanivimab. It attaches to and blocks off the infamous spike proteins on SARS-CoV-2—those sticky suction-cups in illustrations. Partnering with Eli Lilly in a manufacturing agreement, the biotech company brought it to clinical trials in May, just a few months after its work on the deadly pathogen began, after much of the planet became a hot zone.

On November 10—Jenkins's favorite day at the (home) office—the FDA provided Eli Lilly emergency use authorization for bamlanivimab. But she's only mutedly screaming (with joy) inside her heart. "This pandemic isn't 'one morning we're going to wake up and it's all over,'" she says. When it is over, she and her colleagues plan to celebrate their promethean work. "I'm hoping to be able to do it in person," she says. "Until then, I have not taken a breath."