Short Story Contest Winner: "The Gerry Program"

A father and son gaze at the ducks in a lake.

It's an odd sensation knowing you're going to die, but it was a feeling Gerry Ferguson had become relatively acquainted with over the past two years. What most perplexed the terminally ill, he observed, was not the concept of death so much as the continuation of all other life.

Gerry's secret project had been in the works for two years now, ever since they found the growth.

Who will mourn me when I'm gone? What trait or idiosyncrasy will people most recall? Will I still be talked of, 100 years from now?

But Gerry didn't worry about these questions. He was comfortable that his legacy would live on, in one form or another. From his cozy flat in the west end of Glasgow, Gerry had managed to put his affairs in order and still find time for small joys.

Feeding the geese in summer at the park just down from his house, reading classics from the teeming bookcase in the living room, talking with his son Michael on Skype. It was Michael who had first suggested reading some of the new works of non-fiction that now littered the large oak desk in Gerry's study.

He was just finishing 'The Master Algorithm' when his shabby grandfather clock chimed six o'clock. Time to call Michael. Crammed into his tiny study, Gerry pulled his computer's webcam close and waved at Michael's smiling face.

"Hi Dad! How're you today?"

"I'm alright, son. How're things in sunny Australia?"

"Hot as always. How's things in Scotland?"

"I'd 'ave more chance gettin' a tan from this computer screen than I do goin' out there."

Michael chuckled. He's got that hearty Ferguson laugh, Gerry thought.

"How's the project coming along?" Michael asked. "Am I going to see it one of these days?"

"Of course," grinned Gerry, "I designed it for you."

Gerry's secret project had been in the works for two years now, ever since they found the growth. He had decided it was better not to tell Michael. He would only worry.

The two men chatted for hours. They discussed Michael's love life (or lack thereof), memories of days walking in the park, and their shared passion, the unending woes of Rangers Football Club. It wasn't until Michael said his goodbyes that Gerry noticed he'd been sitting in the dark for the best part of three hours, his mesh curtains casting a dim orange glow across the room from the street light outside. Time to get back to work.

*

Every night, Gerry sat at his computer, crawling forums, nourishing his project, feeding his knowledge and debating with other programmers. Even at age 82, Gerry knew more than most about algorithms. Never wanting to feel old, and with all the kids so adept at this digital stuff, Gerry figured he should give the Internet a try too. Besides, it kept his brain active and restored some of the sociability he'd lost in the previous decades as old friends passed away and the physical scope of his world contracted.

This night, like every night, Gerry worked away into the wee hours. His back would ache come morning, but this was the only time he truly felt alive these days. From his snug red brick home in Scotland, Gerry could share thoughts and information with strangers from all over the world. It truly was a miracle of modern science!

*

The next day, Gerry woke to the warm amber sun seeping in between a crack in the curtains. Like every morning, his thoughts took a little time to come into focus. Instinctively his hand went to the other side of the bed. Nobody there. Of course; she was gone. Rita, the sweetest woman he'd ever known. Four years this spring, God rest her soul.

Puttering around the cramped kitchen, Gerry heard a knock at the door. Who could that be? He could see two women standing in the hallway, their bodies contorted in the fisheye glass of the peephole. One looked familiar, but Gerry couldn't be sure. He fiddled with the locks and pulled the door open.

"Hi Gerry. How are you today?"

"Fine, thanks," he muttered, still searching his mind for where he'd seen her face before.

Noting the confusion in his eyes, the woman proffered a hand. "Alice, Alice Corgan. I pop round every now and again to check on you."

It clicked. "Ah aye! Come in, come in. Lemme get ya a cuppa." Gerry turned and shuffled into the flat.

As Gerry set about his tiny kitchen, Alice called from the living room, "This is Mandy. She's a care worker too. She's going to pay you occasional visits if that's alright with you."

Gerry poked his head around the doorway. "I'll always welcome a beautiful young lady in ma home. Though, I've tae warn you I'm a married man, so no funny business." He winked and ducked back into the kitchen.

Alice turned to Mandy with a grin. "He's a good man, our Gerry. You'll get along just fine." She lowered her voice. "As I said, with the Alzheimer's, he has to be reminded to take his medication, but he's still mostly self-sufficient. We installed a medi-bot to remind him every day and dispense the pills. If he doesn't respond, we'll get a message to send someone over."

Mandy nodded and scribbled notes in a pad.

"When I'm gone, Michael will have somethin' to remember me by."

"Also, and this is something we've been working on for a few months now, Gerry is convinced he has something…" her voice trailed off. "He thinks he has cancer. Now, while the Alzheimer's may affect his day-to-day life, it's not at a stage where he needs to be taken into care. The last time we went for a checkup, the doctor couldn't find any sign of cancer. I think it stems from--"

Gerry shouted from the other room: "Does the young lady take sugar?"

"No, I'm fine thanks," Mandy called back.

"Of course you don't," smiled Gerry. "Young lady like yersel' is sweet enough."

*

The following week, Mandy arrived early at Gerry's. He looked unsure at first, but he invited her in.

Sitting on the sofa nurturing a cup of tea, Alice tried to keep things light. "So what do you do in your spare time, Gerry?"

"I've got nothing but spare time these days, even if it's running a little low."

"Do you have any hobbies?"

"Yes actually." Gerry smiled. "I'm makin' a computer program."

Alice was taken aback. She knew very little about computers herself. "What's the program for?" she asked.

"Well, despite ma appearance, I'm no spring chicken. I know I don't have much time left. Ma son, he lives down in Australia now, he worked on a computer program that uses AI - that's artificial intelligence - to imitate a person."

Alice still looked confused, so Gerry pressed on.

"Well, I know I've not long left, so I've been usin' this open source code to make ma own for when I'm gone. I've already written all the code. Now I just have to add the things that make it seem like me. I can upload audio, text, even videos of masel'. That way, when I'm gone, Michael will have somethin' to remember me by."

Mandy sat there, stunned. She had no idea anybody could do this, much less an octogenarian from his small, ramshackle flat in Glasgow.

"That's amazing Gerry. I'd love to see the real thing when you're done."

"O' course. I mean, it'll take time. There's so much to add, but I'll be happy to give a demonstration."

Mandy sat there and cradled her mug. Imagine, she thought, being able to preserve yourself, or at least some basic caricature of yourself, forever.

*

As the weeks went on, Gerry slowly added new shades to his coded double. Mandy would leaf through the dusty photo albums on Gerry's bookcase, pointing to photos and asking for the story behind each one. Gerry couldn't always remember but, when he could, the accompanying stories were often hilarious, incredible, and usually a little of both. As he vividly recounted tales of bombing missions over Burma, trips to the beach with a young Michael and, in one particularly interesting story, giving the finger to Margaret Thatcher, Mandy would diligently record them through a Dictaphone to be uploaded to the program.

Gerry loved the company, particularly when he could regale the young woman with tales of his son Michael. One day, as they sat on the sofa flicking through a box of trinkets from his days as a travelling salesman, Mandy asked why he didn't have a smartphone.

He shrugged. "If I'm out 'n about then I want to see the world, not some 2D version of it. Besides, there's nothin' on there for me."

Alice explained that you could get Skype on a smartphone: "You'd be able to talk with Michael and feed the geese at the park at the same time," she offered.

Gerry seemed interested but didn't mention it again.

"Only thing I'm worried about with ma computer," he remarked, "is if there's another power cut and I can't call Michael. There's been a few this year from the snow 'n I hate not bein' able to reach him."

"Well, if you ever want to use the Skype app on my phone to call him you're welcome," said Mandy. "After all, you just need to add him to my contacts."

Gerry was flattered. "That's a relief, knowing I won't miss out on calling Michael if the computer goes bust."

*

Then, in early spring, just as the first green buds burst forth from the bare branches, Gerry asked Mandy to come by. "Bring that Alice girl if ya can - I know she's excited to see this too."

The next day, Mandy and Alice dutifully filed into the cramped study and sat down on rickety wooden chairs brought from the living room for this special occasion.

An image of Gerry, somewhat younger than the man himself, flashed up on the screen.

With a dramatic throat clearing, Gerry opened the program on his computer. An image of Gerry, somewhat younger than the man himself, flashed up on the screen.

The room was silent.

"Hiya Michael!" AI Gerry blurted. The real Gerry looked flustered and clicked around the screen. "I forgot to put the facial recognition on. Michael's just the go-to name when it doesn't recognize a face." His voice lilted with anxious excitement. "This is Alice," Gerry said proudly to the camera, pointing at Alice, "and this is Mandy."

AI Gerry didn't take his eyes from real Gerry, but grinned. "Hello, Alice. Hiya Mandy." The voice was definitely his, even if the flow of speech was slightly disjointed.

"Hi," Alice and Mandy stuttered.

Gerry beamed at both of them. His eyes flitted between the girls and the screen, perhaps nervous that his digital counterpart wasn't as polished as they'd been expecting.

"You can ask him almost anything. He's not as advanced as the ones they're making in the big studios, but I think Michael will like him."

Alice and Mandy gathered closer to the monitor. A mute Gerry grinned back from the screen. Sitting in his wooden chair, the real Gerry turned to his AI twin and began chattering away: "So, what do you think o' the place? Not bad eh?"

"Oh aye, like what you've done wi' it," said AI Gerry.

"Gerry," Alice cut in. "What did you say about Michael there?"

"Ah, I made this for him. After all, it's the kind o' thing his studio was doin'. I had to clear some space to upload it 'n show you guys, so I had to remove Skype for now, but Michael won't mind. Anyway, Mandy's gonna let me Skype him from her phone."

Mandy pulled her phone out and smiled. "Aye, he'll be able to chat with two Gerry's."

Alice grabbed Mandy by the arm: "What did you tell him?" she whispered, her eyes wide.

"I told him he can use my phone if he wants to Skype Michael. Is that okay?"

Alice turned to Gerry, who was chattering away with his computerized clone. "Gerry, we'll just be one second, I need to discuss something with Mandy."

"Righto," he nodded.

Outside the room, Alice paced up and down the narrow hallway.

Mandy could see how flustered she was. "What's wrong? Don't you like the chatbot? I think it's kinda c-"

"Michael's dead," Alice spluttered.

"What do you mean? He talks to him all the time."

Alice sighed. "He doesn't talk to Michael. See, a few years back, Michael found out he had cancer. He worked for this company that did AI chatbot stuff. When he knew he was dying he--" she groped in the air for the words-- "he built this chatbot thing for Gerry, some kind of super-advanced AI. Gerry had just been diagnosed with Alzheimer's and I guess Michael was worried Gerry would forget him. He designed the chatbot to say he was in Australia to explain why he couldn't visit."

"That's awful," Mandy granted, "but I don't get what the problem is. I mean, surely he can show the AI Michael his own chatbot?"

"No, because you can't get the AI Michael on Skype. Michael just designed the program to look like Skype."

"But then--" Mandy went silent.

"Michael uploaded the entire AI to Gerry's computer before his death. Gerry didn't delete Skype. He deleted the AI Michael."

"So… that's it? He-he's gone?" Mandy's voice cracked. "He can't just be gone, surely he can't?"

The women stood staring at each other. They looked to the door of the study. They could still hear Gerry, gabbing away with his cybercopy.

"I can't go back in there," muttered Mandy. Her voice wavered as she tried to stem the misery rising in her throat.

Alice shook her head and paced the floor. She stopped and stared at Mandy with grim resignation. "We don't have a choice."

When they returned, Gerry was still happily chatting away.

"Hiya girls. Ya wanna ask my handsome twin any other questions? If not, we could get Michael on the phone?"

Neither woman spoke. Gerry clapped his hands and turned gaily to the monitor again: "I cannae wait for ya t'meet him, Gerry. He's gonna be impressed wi' you."

Alice clasped her hands to her mouth. Tears welled in the women's eyes as they watched the old man converse with his digital copy. The heat of the room seemed to swell, becoming insufferable. Mandy couldn't take it anymore. She jumped up, bolted to the door and collapsed against a wall in the hallway. Alice perched on the edge of her seat in a dumb daze, praying for the floor to open and swallow the contents of the room whole.

Oblivious, Gerry and his echo babbled away, the blue glow of the screen illuminating his euphoric face. "Just wait until y'meet him Gerry, just wait."

Here's What It Looks Like to Seek Therapy for Climate Change Anxiety

Treatment for climate change anxiety looks different from treating generalized anxiety in that the concerns have a legitimate basis, therapists say.

Three months after Gretchen bought a house in Grass Valley, California, the most destructive and fatal wildfire in the state's history ravaged the towns about 40 miles northwest of her.

"For a long time, I kept on having this vision of what my town will look like if one of those firestorms happens, and I felt like I needed to work on that."

The Camp Fire of November 2018 was noteworthy not just because of its damaging scale but because of what started it all: a spark from a faulty transmission line owned by the Pacific Gas & Electric Company, which services nearly two-thirds of California.

PG&E reacted by announcing almost a year later that in advance of days with a high fire risk, it would proactively institute power outages in 17 counties throughout the northern part of the state, including the one where Gretchen lives. The binary options seemed to be: cause another fire or intermittently plunge tens of thousands of people into literal and figurative darkness, impacting emergency services, health, food, internet, gas, and any other electrified necessity or convenience of modern life.

This summer, in between the end of the Camp Fire and the beginning of the blackouts, Gretchen, who asked to keep her last name private, decided it was time to seek counseling for climate-related anxiety.

"That was a very traumatic experience to go through," Gretchen, 39, says, describing what it was like to have recently settled in this increasingly fire-prone part of her home state, and later witnessing a colleague flee California altogether after his own home burned down and he couldn't afford to stay. "For a long time, I kept on having this vision of what my town will look like if one of those firestorms happens, and I felt like I needed to work on that."

While research on climate anxiety—or, more broadly, the effects of climate change on mental health—has been slowly but surely piling up, the actual experience of diagnosing and treating it is less well-documented in both media and academia. An ongoing Yale University study of American perceptions of climate change shows an increasing proportion of concern: In 2018, 29 percent of 1,114 survey respondents said they were "very worried" about climate change, up from 16 percent in 2008. But there are no parallel large-scale studies of whether a similar proportion of people are in therapy for climate change-related mental health issues.

That might be because many would-be clients don't yet realize that this is a valid concern for which to seek out professional support. It could also be because there are no definitive or unifying resources for therapists who are counseling people on the topic. Climate anxiety is notably absent by name from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the psychological gospel for everyone from clinicians to lawmakers. The manual was last updated in 2012 (and published in 2013), just when the first documents of climate anxiety were beginning to crop up.

A small 2013 study surveyed college students in the U.S. and Europe to try and answer the question: Is habitually worrying about the environment a mental health concern if it's a response to a real threat? The study concluded: "...those who habitually worry about the ecology are not only lacking in any psychopathology, but demonstrate a constructive and adaptive response to a serious problem." In other words, worrying about a concrete external concern like the state of the environment is on a different plane than habitually worrying about an internal concern, like feelings of inadequacy. Therapy may still help with the former, but the diagnostic framework could ultimately look different than what is typically used in generalized anxiety.

For now, the best resource for therapists counseling patients battling what is sometimes dubbed "ecoanxiety" is a 70-page booklet called "Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Implications, and Guidance," whose publication was co-sponsored by the American Psychological Association, which publishes the DSM. It's been through two editions already, the first in 2014 and the second in 2017.

"It's not clear to me that [climate anxiety] would merit its own diagnosis, at least at this point," says Susan Clayton, who was the lead author on the 2017 edition and who studies this area at The College of Wooster, but doesn't counsel people directly. However, she says, "I do think that there are some differences [from generalized anxiety], and one of the important differences is, of course, that there's some realism here."

Clayton says that group therapy may be a particularly useful way to affirm for people that they're not the only one experiencing climate anxiety, especially in communities where it might be taboo to not only affirm the existence of climate change but to be openly affected by it.

On drawing therapeutic inspiration from historical examples of other global dangers—such as the widespread fear of nuclear threat during the Cold War—Clayton says: "That was such a different time and they were thinking differently about mental health, but I think in many ways the fear is very similar. It's not like worrying about your finances, it's worrying about the end of the world. So that sort of existential component, and the fact that it's shared, both are very similar here."

There are precedents that therapists can refer to for guidance on helping clients managing climate anxiety, like the approaches used to support people dealing with a terminal illness or battling systemic racism. Such treatments need to stay rooted in the reality of the trigger.

"You don't want to say to them, 'That's not a real thing,'" Clayton explains. "So I think of [climate anxiety] like that. It does mean that the therapeutic focus is not going to be on trying to get people to be reasonable," which is to say that their anxiety is not inherently unreasonable.

"I think it is important to recognize that the anxieties have a legitimate basis," she adds.

"I feel more comfortable now being prepared, being prudent, but not dwelling on it all the time."

Gretchen's reality is now one of adapting to living an off-the-grid lifestyle that she didn't intentionally sign up for. She puts gas in her car in advance of blackouts, and waits to see week-by-week if the school where she teaches second and third grade, in the foothills of Tahoe National Park, will be closed. Her union has yet to figure out how this stop-and-go schedule will affect her salary; she has to keep rescheduling parent-teacher conferences; and she no longer knows when the last day of school will be—existing summer plans for her personal life be damned. Even her interview for this story was affected by this instability.

While trying to schedule a time to talk, she wrote, "Speaking of climate change, I may not have work the rest of the week due to PG&E power outages. If so I will have a very flexible schedule." Later, she suddenly had to decline. "As it turns out, the power's not going out. I will be at work."

In therapy sessions, she works with her counselor to focus on preparedness, where possible, and to specifically frame that preparedness as a source of regaining some of the stability she's lost rather than a sign of imminent trouble. That nuance became necessary after a training at work had the opposite effect.

"We've gone through scenarios [where] if a firestorm happens and we don't have time to evacuate, we have to gather all the children into the cafeteria and fend off the flames ourselves with help from the fire department, and keep them alive if we can't get out in time," she says. "After that day, or that training, that really scared me."

Her therapist uses a type of psychotherapy called eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) to help Gretchen move away from traumatizing images, such as picturing her town on fire, while emphasizing what it is that she can control, such as making sure her car has a full tank, in case she needs to evacuate. EMDR has been shown to help people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and the World Health Organization offers practice guidelines around it.

"I feel more comfortable now being prepared, being prudent, but not dwelling on it all the time," she says. "I feel a little less heightened anxiety and have stopped replaying [those images] in my mind."

Overall, the type of support Gretchen receives is based on pre-existing tools for managing other well-established mental health burdens like PTSD and generalized anxiety. Although no definitive, new practices have specifically emerged around climate anxiety on a comprehensive scale yet, Gretchen says she was nonetheless met with compassion when she first approached a therapist about the topical source of her anxiety, and doesn't feel that her care is lacking in any way.

"I don't know enough to know whether or how it should become its own diagnosis, but I feel like it's something that is still evolving. Down the road, as we see more populations having to move, more refugees, more real effects, that might change," she says. "For me, using the old tools in a new way has been effective at this point."

Gretchen hasn't yet explored with her therapist the more existential worries that climate change dredges up for her—worries about whether or not to have children, and if it was a mistake to settle down in Grass Valley. She's only been in therapy for her climate anxiety since the summer (although she has intermittently sought out professional mental health support for other reasons over the last eight years), and it will take time to get to these bigger issues, she says. She's not sure yet whether that part of her counseling will look different than what's she's done so far.

But she does wonder about the overall usefulness of pathologizing what, as Clayton said, are legitimate anxieties. She has the same question when it comes to providing mental health support for her students, many of whom live in poverty.

"Is it just putting a bandaid on something that is unfixable, or is unfair?" she ponders. But de-escalating the psychological toll that climate change can have on people is crucial to giving them back the energy to deal with the problem itself, not just their reaction to the problem. Clayton believes that engaging in climate activism can provide solace for the people who do have that energy.

"This is a social issue, and there's obviously lots and lots of climate activism," she says. "You might not be comfortable being politically active, but I think getting involved in some way, and addressing the issue, would help people feel much more empowered, and would help with the experience of climate anxiety."

"Remember that nature is not just a source of anxiety, it's also a source of replenishment and restoration."

As far as what shape this personal involvement takes, an increasingly vocal movement of people is calling for a refocus. They say the onus of reversing, or at least stymying, the situation should fall on the big businesses and governments that have been too slow to act, not on individual consumer actions, like buying sustainably made clothes, divesting from the meat and dairy industry, or driving an electric car.

But outside of formal therapy and even activism, however that looks, Clayton has another suggestion for combating climate anxiety, and it's one that is surprising in its simplicity: Go outside, and take stock of that which boldly continues to exist.

"People who are anxious about climate change, it's partly about the survival of the species, but it's partly about the sense that, 'Something I care about is being destroyed,'" she says. "Remember that nature is not just a source of anxiety, it's also a source of replenishment and restoration."

Three Big Biotech Ideas to Watch in 2020—And Beyond

Body-on-a-chip, prime editing, and gut microbes all are poised to make a big impact in 2020.

1. Happening Now: Body-on-a-Chip Technology Is Enabling Safer Drug Trials and Better Cancer Research

Researchers have increasingly used the technology known as "lab-on-a-chip" or "organ-on-a-chip" to test the effects of pharmaceuticals, toxins, and chemicals on humans. Rather than testing on animals, which raises ethical concerns and can sometimes be inaccurate, and human-based clinical trials, which can be expensive and difficult to iterate, scientists turn to tiny, micro-engineered chips—about the size of a thumb drive.

It's possible that doctors could one day take individual cell samples and create personalized treatments, testing out any medications on the chip.

The chips are lined with living samples of human cells, which mimic the physiology and mechanical forces experienced by cells inside the human body, down to blood flow and breathing motions; the functions of organs ranging from kidneys and lungs to skin, eyes, and the blood-brain barrier.

A more recent—and potentially even more useful—development takes organ-on-a-chip technology to the next level by integrating several chips into a "body-on-a-chip." Since human organs don't work in isolation, seeing how they all react—and interact—once a foreign element has been introduced can be crucial to understanding how a certain treatment will or won't perform. Dr. Shyni Varghese, a MEDx investigator at the Duke University School of Medicine, is one of the researchers working with these systems in order to gain a more nuanced understanding of how multiple different organs react to the same stimuli.

Her lab is working on "tumor-on-a-chip" models, which can not only show the progression and treatment of cancer, but also model how other organs would react to immunotherapy and other drugs. "The effect of drugs on different organs can be tested to identify potential side effects," Varghese says. In addition, these models can help the researchers figure out how cancers grow and spread, as well as how to effectively encourage immune cells to move in and attack a tumor.

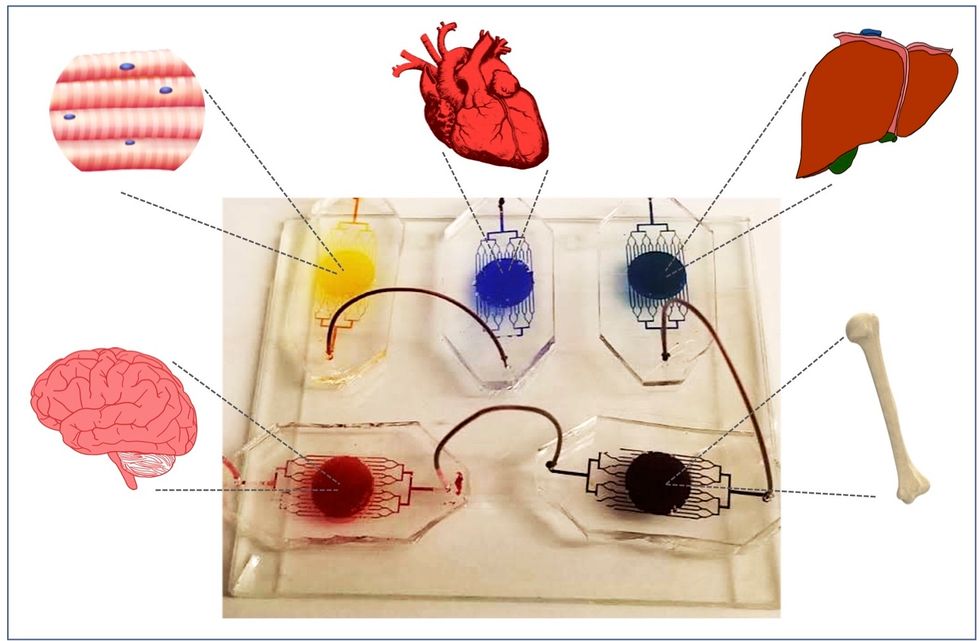

One body-on-a-chip used by Dr. Varghese's lab tracks the interactions of five organs—brain, heart, liver, muscle, and bone.

As their research progresses, Varghese and her team are looking for ways to maintain the long-term function of the engineered organs. In addition, she notes that this kind of research is not just useful for generalized testing; "organ-on-chip technologies allow patient-specific analyses, which can be used towards a fundamental understanding of disease progression," Varghese says. It's possible that doctors could one day take individual cell samples and create personalized treatments, testing out any medications on the chip for safety, efficacy, and potential side effects before writing a prescription.

2. Happening Soon: Prime Editing Will Have the Power to "Find and Replace" Disease-Causing Genes

Biochemist David Liu made industry-wide news last fall when he and his lab at MIT's Broad Institute, led by Andrew Anzalone, published a paper on prime editing: a new, more focused technology for editing genes. Prime editing is a descendant of the CRISPR-Cas9 system that researchers have been working with for years, and a cousin to Liu's previous innovation—base editing, which can make a limited number of changes to a single DNA letter at a time.

By contrast, prime editing has the potential to make much larger insertions and deletions; it also doesn't require the tweaked cells to divide in order to write the changes into the DNA, which could make it especially suitable for central nervous system diseases, like Parkinson's.

Crucially, the prime editing technique has a much higher efficiency rate than the older CRISPR system, and a much lower incidence of accidental insertions or deletions, which can make dangerous changes for a patient.

It also has a very broad potential range: according to Liu, 89% of the pathogenic mutations that have been collected in ClinVar (a public archive of human variations) could, in principle, be treated with prime editing—although he is careful to note that correcting a single genetic mutation may not be sufficient to fully treat a genetic disease.

Figuring out just how prime editing can be used most effectively and safely will be a long process, but it's already underway. The same day that Liu and his team posted their paper, they also made the basic prime editing constructs available for researchers around the world through Addgene, a plasmid repository, so that others in the scientific community can test out the technique for themselves. It might be years before human patients will see the results, and in the meantime, significant bioethical questions remain about the limits and sociological effects of such a powerful gene-editing tool. But in the long fight against genetic diseases, it's a huge step forward.

3. Happening When We Fund It: Focusing on Microbiome Health Could Help Us Tackle Social Inequality—And Vice Versa

The past decade has seen a growing awareness of the major role that the microbiome, the microbes present in our digestive tract, play in human health. Having a less-healthy microbiome is correlated with health risks like diabetes and depression, and interventions that target gut health, ranging from kombucha to fecal transplants, have cropped up with increasing frequency.

New research from the University of Maine's Dr. Suzanne Ishaq takes an even broader view, arguing that low-income and disadvantaged populations are less likely to have healthy, diverse gut bacteria, and that increasing access to beneficial microorganisms is an important juncture of social justice and public health.

"Basically, allowing people to lead healthy lives allows them to access and recruit microbes."

"Typically, having a more diverse bacterial community is associated with health, and having fewer different species is associated with illness and may leave you open to infection from bacteria that are good at exploiting opportunities," Ishaq says.

Having a healthy biome doesn't mean meeting one fixed ratio of gut bacteria, since different combinations of microbes can generate roughly similar results when they work in concert. Generally, "good" microbes are the ones that break down fiber and create the byproducts that we use for energy, or ones like lactic acid bacteria that work to make microbials and keep other bacteria in check. The microbial universe in your gut is chaotic, Ishaq says. "Microbes in your gut interact with each other, with you, with your food, or maybe they don't interact at all and pass right through you." Overall, it's tricky to name specific microbial communities that will make or break someone's health.

There are important corollaries between environment and biome health, though, which Ishaq points out: Living in urban environments reduces microbial exposure, and losing the microorganisms that humans typically source from soil and plants can reduce our adaptive immunity and ability to fight off conditions like allergies and asthma. Access to green space within cities can counteract those effects, but in the U.S. that access varies along income, education, and racial lines. Likewise, lower-income communities are more likely to live in food deserts or areas where the cheapest, most convenient food options are monotonous and low in fiber, further reducing microbial diversity.

Ishaq also suggests other areas that would benefit from further study, like the correlation between paid family leave, breastfeeding, and gut microbiota. There are technical and ethical challenges to direct experimentation with human populations—but that's not what Ishaq sees as the main impediment to future research.

"The biggest roadblock is money, and the solution is also money," she says. "Basically, allowing people to lead healthy lives allows them to access and recruit microbes."

That means investment in things we already understand to improve public health, like better education and healthcare, green space, and nutritious food. It also means funding ambitious, interdisciplinary research that will investigate the connections between urban infrastructure, housing policy, social equity, and the millions of microbes keeping us company day in and day out.