Smartwatches can track COVID-19 symptoms, study finds

University of Michigan researchers found that new signals embedded in heart rate indicated when individuals were infected with COVID-19 and how ill they became.

If a COVID-19 infection develops, a wearable device may eventually be able to clue you in. A study at the University of Michigan found that a smartwatch can monitor how symptoms progress.

The study evaluated the effects of COVID-19 with various factors derived from heart-rate data. This method also could be employed to detect other diseases, such as influenza and the common cold, at home or when medical resources are limited, such as during a pandemic or in developing countries.

Tracking students and medical interns across the country, the University of Michigan researchers found that new signals embedded in heart rate indicated when individuals were infected with COVID-19 and how ill they became.

For instance, they discovered that individuals with COVID-19 experienced an increase in heart rate per step after the onset of their symptoms. Meanwhile, people who reported a cough as one of their COVID-19 symptoms had a much more elevated heart rate per step than those without a cough.

“We previously developed a variety of algorithms to analyze data from wearable devices. So, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, it was only natural to apply some of these algorithms to see if we can get a better understanding of disease progression,” says Caleb Mayer, a doctoral student in mathematics at the University of Michigan and a co-first author of the study.

People may not internally sense COVID-19’s direct impact on the heart, but “heart rate is a vital sign that gives a picture of overall health," says Daniel Forger, a University of Michigan professor.

Millions of people are tracking their heart rate through wearable devices. This information is already generating a tremendous amount of data for researchers to analyze, says co-author Daniel Forger, professor of mathematics and research professor of computational medicine and bioinformatics at the University of Michigan.

“Heart rate is affected by many different physiological signals,” Forger explains. “For instance, if your lungs aren’t functioning properly, your heart may need to beat faster to meet metabolic demands. Your heart rate has a natural daily rhythm governed by internal biological clocks.” While people may not internally sense COVID-19’s direct impact on the heart, he adds that “heart rate is a vital sign that gives a picture of overall health.”

Among the total of 2,164 participants who enrolled in the student study, 72 undergraduate and graduate students contracted COVID-19, providing wearable data from 50 days before symptom onset to 14 days after. The researchers also analyzed this type of data for 43 medical interns from the Intern Health Study by the Michigan Neuroscience Institute and 29 individuals (who are not affiliated with the university) from the publicly available dataset.

Participants could wear the device on either wrist. They also documented their COVID-19 symptoms, such as fever, shortness of breath, cough, runny nose, vomiting, diarrhea, body aches, loss of taste, loss of smell, and sore throat.

Experts not involved in the study found the research to be productive. “This work is pioneering and reveals exciting new insights into the many important ways that we can derive clinically significant information about disease progression from consumer-grade wearable devices,” says Lisa A. Marsch, director of the Center for Technology and Behavioral Health and a professor in the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College. “Heart-rate data are among the highest-quality data that can be obtained via wearables.”

Beyond the heart, she adds, “Wearable devices are providing novel insights into individuals’ physiology and behavior in many health domains.” In particular, “this study beautifully illustrates how digital-health methodologies can markedly enhance our understanding of differences in individuals’ experience with disease and health.”

Previous studies had demonstrated that COVID-19 affects cardiovascular functions. Capitalizing on this knowledge, the University of Michigan endeavor took “a giant step forward,” says Gisele Oda, a researcher at the Institute of Biosciences at the University of Sao Paulo in Brazil and an expert in chronobiology—the science of biological rhythms. She commends the researchers for developing a complex algorithm that “could extract useful information beyond the established knowledge that heart rate increases and becomes more irregular in COVID patients.”

Wearable devices open the possibility of obtaining large-scale, long, continuous, and real-time heart-rate data on people performing everyday activities or while sleeping. “Importantly, the conceptual basis of this algorithm put circadian rhythms at the center stage,” Oda says, referring to the physical, mental, and behavioral changes that follow a 24-hour cycle. “What we knew before was often based on short-time heart rate measured at any time of day,” she adds, while noting that heart rate varies between day and night and also changes with activity.

However, without comparison to a control group of people having the common flu, it is difficult to determine if the heart-rate signals are unique to COVID-19 or also occur with other illnesses, says John Torous, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School who has researched wearable devices. In addition, he points to recent data showing that many wearables, which work by beaming light through the skin, may be less accurate in people with darker skin due to variations in light absorption.

While the results sound interesting, they lack the level of conclusive evidence that would be needed to transform how physicians care for patients. “But it is a good step in learning more about what these wearables can tell us,” says Torous, who is also director of digital psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, a Harvard affiliate, in Boston. A follow-up step would entail replicating the results in a different pool of people to “help us realize the full value of this work.”

It is important to note that this research was conducted in university settings during the early phases of the pandemic, with remote learning in full swing amid strict isolation and quarantine mandates in effect. The findings demonstrate that physiological monitoring can be performed using consumer-grade wearable sensors, allowing research to continue without in-person contact, says Sung Won Choi, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Michigan who is principal investigator of the student study.

“The worldwide COVID-19 pandemic interrupted a lot of activities that relied on face-to-face interactions, including clinical research,” Choi says. “Mobile technology proved to be tremendously beneficial during that time, because it allowed us to collect detailed physiological data from research participants remotely over an entire semester.” In fact, the researchers did not have any in-person contact with the students involved in the study. “Everything was done virtually," Choi explains. "Importantly, their willingness to participate in research and share data during this historical time, combined with the capacity of secure cloud storage and novel mathematical analytics, enabled our research teams to identify unique patterns in heart-rate data associated with COVID-19.”

Vaccines Without Vaccinations Won’t End the Pandemic

In this 2020 photograph, a bandage is placed on a patient who has just received a vaccine.

COVID-19 vaccine development has advanced at a record-setting pace, thanks to our nation's longstanding support for basic vaccine science coupled with massive public and private sector investments.

Yet, policymakers aren't according anywhere near the same level of priority to investments in the social, behavioral, and data science needed to better understand who and what influences vaccination decision-making. "If we want to be sure vaccines become vaccinations, this is exactly the kind of work that's urgently needed," says Dr. Bruce Gellin, President of Global Immunization at the Sabin Vaccine Institute.

Simply put: it's possible vaccines will remain in refrigerators and not be delivered to the arms of rolled-up sleeves if we don't quickly ramp up vaccine confidence research and broadly disseminate the findings.

According to the most recent Gallup poll, the share of U.S. adults who say they would get a COVID-19 vaccine rose to 58 percent this month from 50 percent in September, with non-white Americans and those ages 45-65 even less willing to be vaccinated. While there is still much we don't understand about COVID-19, we do know that without high levels of immunity in the population, a return to some semblance of normalcy is wishful thinking.

Research from prior vaccination campaigns such as H1N1, HPV, and the annual flu points us in the right direction. Key components of successful vaccination efforts require 1) Identifying the concerns of particular segments of the population; 2) Tailoring messages and incentives to address those concerns, and 3) Reaching out through trusted sources – health care providers, public health departments, and others in the community.

Research during the H1N1 flu found preparing people for some uncertainty actually improved trust, according to Dr. Sandra Crouse Quinn, professor and chair, Family Science, University of Maryland. Dr. Crouse Quinn's research during that period also underscored the need to address the specific vaccine concerns of racial and ethnic groups.

The stunning scientific achievement of COVID-19 vaccines anticipated to be ready in record time needs to be backed up by an equally ambitious and evidence-based effort to build the public's confidence in the vaccines.

Data science has provided crucial insight about the social media universe. Dr. Neil Johnson, a scientist at George Washington University, found that despite having fewer followers, anti-vaccination pages are more numerous and growing faster than pro-vaccination pages. They are more often linked to in discussions on other Facebook pages – such as school parent associations – where people are undecided about vaccination.

We've learned about building vaccine confidence from earlier campaigns. Now, however, we are faced with a unique and challenging set of obstacles to unpack quickly: How do we communicate the importance of eventual COVID-19 vaccines to Americans in light of the muddled-to-poor messaging from political leaders, the weaponizing of relatively simple public health recommendations, the enormous disproportionate toll on people of color, and the torrent of online misinformation? We urgently need data reflective of today's circumstances along with the policy to ensure it is quickly and effectively disseminated to the public health and clinical workforce.

Last year prompted in part by the measles outbreaks, Reps. Michael C. Burgess (R-TX) and Kim Shrier (D-WA), both physicians, introduced the bipartisan Vaccines Act to develop a national surveillance system to monitor vaccination rates and conduct a national campaign to increase awareness of the importance of vaccines. Unfortunately, that legislation wasn't passed. In response to COVID-19, Senate HELP Committee Ranking member Patty Murray (D-WA) has sought funds to strengthen vaccine confidence and combat misinformation with federally supported communication, research, and outreach efforts. Leading experts outside of Congress have called for this type of research, including the Sabin-Aspen Vaccine Science Policy Institute. Most recently, the National Academy of Sciences, in its report regarding the equitable distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine, included as one of its recommendations the need for "a rapid-response program to advance the science behind vaccine confidence."

Addressing trust in vaccination has never been as challenging nor as consequential. The stunning scientific achievement of COVID-19 vaccines anticipated to be ready in record time needs to be backed up by an equally ambitious and evidence-based effort to build the public's confidence in the vaccines. In its remaining days, the Trump Administration should invest in building vaccine confidence with current resources, targeting efforts to ensure COVID vaccines reduce rather than exacerbate racial and ethnic health disparities. Congress must also act to provide the additional research and outreach resources needed as well as pass the Vaccines Act so we are better prepared in the future.

If we don't succeed, COVID-19 will continue wreaking havoc on our health, our society, and our economy. We will also permanently jeopardize public trust in vaccines – one of the most successful medical interventions in human history.

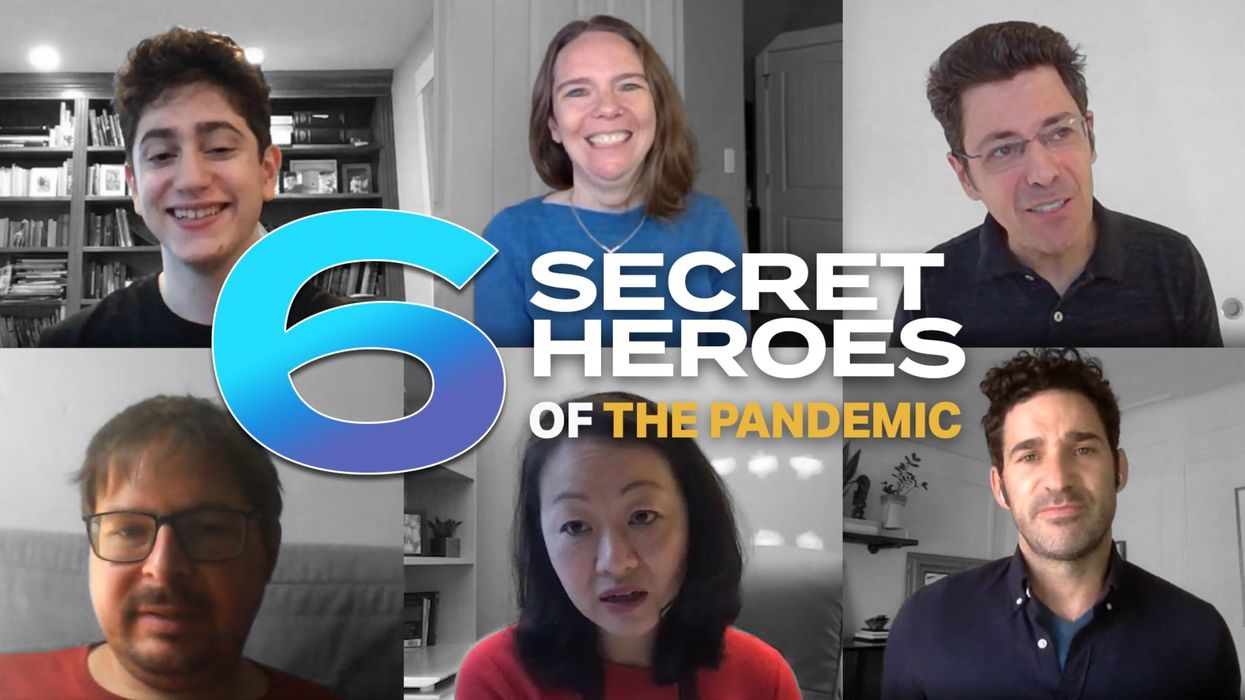

New Video: Secret Heroes of the Pandemic

These 6 people deserve to be widely known and celebrated for their brave and ingenious contributions to battling the pandemic.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.