Smartwatches can track COVID-19 symptoms, study finds

University of Michigan researchers found that new signals embedded in heart rate indicated when individuals were infected with COVID-19 and how ill they became.

If a COVID-19 infection develops, a wearable device may eventually be able to clue you in. A study at the University of Michigan found that a smartwatch can monitor how symptoms progress.

The study evaluated the effects of COVID-19 with various factors derived from heart-rate data. This method also could be employed to detect other diseases, such as influenza and the common cold, at home or when medical resources are limited, such as during a pandemic or in developing countries.

Tracking students and medical interns across the country, the University of Michigan researchers found that new signals embedded in heart rate indicated when individuals were infected with COVID-19 and how ill they became.

For instance, they discovered that individuals with COVID-19 experienced an increase in heart rate per step after the onset of their symptoms. Meanwhile, people who reported a cough as one of their COVID-19 symptoms had a much more elevated heart rate per step than those without a cough.

“We previously developed a variety of algorithms to analyze data from wearable devices. So, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, it was only natural to apply some of these algorithms to see if we can get a better understanding of disease progression,” says Caleb Mayer, a doctoral student in mathematics at the University of Michigan and a co-first author of the study.

People may not internally sense COVID-19’s direct impact on the heart, but “heart rate is a vital sign that gives a picture of overall health," says Daniel Forger, a University of Michigan professor.

Millions of people are tracking their heart rate through wearable devices. This information is already generating a tremendous amount of data for researchers to analyze, says co-author Daniel Forger, professor of mathematics and research professor of computational medicine and bioinformatics at the University of Michigan.

“Heart rate is affected by many different physiological signals,” Forger explains. “For instance, if your lungs aren’t functioning properly, your heart may need to beat faster to meet metabolic demands. Your heart rate has a natural daily rhythm governed by internal biological clocks.” While people may not internally sense COVID-19’s direct impact on the heart, he adds that “heart rate is a vital sign that gives a picture of overall health.”

Among the total of 2,164 participants who enrolled in the student study, 72 undergraduate and graduate students contracted COVID-19, providing wearable data from 50 days before symptom onset to 14 days after. The researchers also analyzed this type of data for 43 medical interns from the Intern Health Study by the Michigan Neuroscience Institute and 29 individuals (who are not affiliated with the university) from the publicly available dataset.

Participants could wear the device on either wrist. They also documented their COVID-19 symptoms, such as fever, shortness of breath, cough, runny nose, vomiting, diarrhea, body aches, loss of taste, loss of smell, and sore throat.

Experts not involved in the study found the research to be productive. “This work is pioneering and reveals exciting new insights into the many important ways that we can derive clinically significant information about disease progression from consumer-grade wearable devices,” says Lisa A. Marsch, director of the Center for Technology and Behavioral Health and a professor in the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College. “Heart-rate data are among the highest-quality data that can be obtained via wearables.”

Beyond the heart, she adds, “Wearable devices are providing novel insights into individuals’ physiology and behavior in many health domains.” In particular, “this study beautifully illustrates how digital-health methodologies can markedly enhance our understanding of differences in individuals’ experience with disease and health.”

Previous studies had demonstrated that COVID-19 affects cardiovascular functions. Capitalizing on this knowledge, the University of Michigan endeavor took “a giant step forward,” says Gisele Oda, a researcher at the Institute of Biosciences at the University of Sao Paulo in Brazil and an expert in chronobiology—the science of biological rhythms. She commends the researchers for developing a complex algorithm that “could extract useful information beyond the established knowledge that heart rate increases and becomes more irregular in COVID patients.”

Wearable devices open the possibility of obtaining large-scale, long, continuous, and real-time heart-rate data on people performing everyday activities or while sleeping. “Importantly, the conceptual basis of this algorithm put circadian rhythms at the center stage,” Oda says, referring to the physical, mental, and behavioral changes that follow a 24-hour cycle. “What we knew before was often based on short-time heart rate measured at any time of day,” she adds, while noting that heart rate varies between day and night and also changes with activity.

However, without comparison to a control group of people having the common flu, it is difficult to determine if the heart-rate signals are unique to COVID-19 or also occur with other illnesses, says John Torous, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School who has researched wearable devices. In addition, he points to recent data showing that many wearables, which work by beaming light through the skin, may be less accurate in people with darker skin due to variations in light absorption.

While the results sound interesting, they lack the level of conclusive evidence that would be needed to transform how physicians care for patients. “But it is a good step in learning more about what these wearables can tell us,” says Torous, who is also director of digital psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, a Harvard affiliate, in Boston. A follow-up step would entail replicating the results in a different pool of people to “help us realize the full value of this work.”

It is important to note that this research was conducted in university settings during the early phases of the pandemic, with remote learning in full swing amid strict isolation and quarantine mandates in effect. The findings demonstrate that physiological monitoring can be performed using consumer-grade wearable sensors, allowing research to continue without in-person contact, says Sung Won Choi, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Michigan who is principal investigator of the student study.

“The worldwide COVID-19 pandemic interrupted a lot of activities that relied on face-to-face interactions, including clinical research,” Choi says. “Mobile technology proved to be tremendously beneficial during that time, because it allowed us to collect detailed physiological data from research participants remotely over an entire semester.” In fact, the researchers did not have any in-person contact with the students involved in the study. “Everything was done virtually," Choi explains. "Importantly, their willingness to participate in research and share data during this historical time, combined with the capacity of secure cloud storage and novel mathematical analytics, enabled our research teams to identify unique patterns in heart-rate data associated with COVID-19.”

Could this habit related to eating slow down rates of aging?

Previous research showed that restricting calories results in longer lives for mice, worms and flies. A new study by Columbia University researchers applied those findings to people. But what does this paper actually show?

Last Thursday, scientists at Columbia University published a new study finding that cutting down on calories could lead to longer, healthier lives. In the phase 2 trial, 220 healthy people without obesity dropped their calories significantly and, at least according to one test, their rate of biological aging slowed by 2 to 3 percent in over a couple of years. Small though that may seem, the researchers estimate that it would translate into a decline of about 10 percent in the risk of death as people get older. That's basically the same as quitting smoking.

Previous research has shown that restricting calories results in longer lives for mice, worms and flies. This research is unique because it applies those findings to people. It was published in Nature Aging.

But what did the researchers actually show? Why did two other tests indicate that the biological age of the research participants didn't budge? Does the new paper point to anything people should be doing for more years of healthy living? Spoiler alert: Maybe, but don't try anything before talking with a medical expert about it. I had the chance to chat with someone with inside knowledge of the research -- Dr. Evan Hadley, director of the National Institute of Aging's Division of Geriatrics and Clinical Gerontology, which funded the study. Dr. Hadley describes how the research participants went about reducing their calories, as well as the risks and benefits involved. He also explains the "aging clock" used to measure the benefits.

Evan Hadley, Director of the Division of Geriatrics and Clinical Gerontology at the National Institute of Aging

NIA

Scientists are making machines, wearable and implantable, to act as kidneys

Recent advancements in engineering mean that the first preclinical trials for an artificial kidney could happen soon.

Like all those whose kidneys have failed, Scott Burton’s life revolves around dialysis. For nearly two decades, Burton has been hooked up (or, since 2020, has hooked himself up at home) to a dialysis machine that performs the job his kidneys normally would. The process is arduous, time-consuming, and expensive. Except for a brief window before his body rejected a kidney transplant, Burton has depended on machines to take the place of his kidneys since he was 12-years-old. His whole life, the 39-year-old says, revolves around dialysis.

“Whenever I try to plan anything, I also have to plan my dialysis,” says Burton says, who works as a freelance videographer and editor. “It’s a full-time job in itself.”

Many of those on dialysis are in line for a kidney transplant that would allow them to trade thrice-weekly dialysis and strict dietary limits for a lifetime of immunosuppressants. Burton’s previous transplant means that his body will likely reject another donated kidney unless it matches perfectly—something he’s not counting on. It’s why he’s enthusiastic about the development of artificial kidneys, small wearable or implantable devices that would do the job of a healthy kidney while giving users like Burton more flexibility for traveling, working, and more.

Still, the devices aren’t ready for testing in humans—yet. But recent advancements in engineering mean that the first preclinical trials for an artificial kidney could happen soon, according to Jonathan Himmelfarb, a nephrologist at the University of Washington.

“It would liberate people with kidney failure,” Himmelfarb says.

An engineering marvel

Compared to the heart or the brain, the kidney doesn’t get as much respect from the medical profession, but its job is far more complex. “It does hundreds of different things,” says UCLA’s Ira Kurtz.

Kurtz would know. He’s worked as a nephrologist for 37 years, devoting his career to helping those with kidney disease. While his colleagues in cardiology and endocrinology have seen major advances in the development of artificial hearts and insulin pumps, little has changed for patients on hemodialysis. The machines remain bulky and require large volumes of a liquid called dialysate to remove toxins from a patient’s blood, along with gallons of purified water. A kidney transplant is the next best thing to someone’s own, functioning organ, but with over 600,000 Americans on dialysis and only about 100,000 kidney transplants each year, most of those in kidney failure are stuck on dialysis.

Part of the lack of progress in artificial kidney design is the sheer complexity of the kidney’s job. Each of the 45 different cell types in the kidney do something different.

Part of the lack of progress in artificial kidney design is the sheer complexity of the kidney’s job. To build an artificial heart, Kurtz says, you basically need to engineer a pump. An artificial pancreas needs to balance blood sugar levels with insulin secretion. While neither of these tasks is simple, they are fairly straightforward. The kidney, on the other hand, does more than get rid of waste products like urea and other toxins. Each of the 45 different cell types in the kidney do something different, helping to regulate electrolytes like sodium, potassium, and phosphorous; maintaining blood pressure and water balance; guiding the body’s hormonal and inflammatory responses; and aiding in the formation of red blood cells.

There's been little progress for patients during Ira Kurtz's 37 years as a nephrologist. Artificial kidneys would change that.

UCLA

Dialysis primarily filters waste, and does so well enough to keep someone alive, but it isn’t a true artificial kidney because it doesn’t perform the kidney’s other jobs, according to Kurtz, such as sensing levels of toxins, wastes, and electrolytes in the blood. Due to the size and water requirements of existing dialysis machines, the equipment isn’t portable. Physicians write a prescription for a certain duration of dialysis and assess how well it’s working with semi-regular blood tests. The process of dialysis itself, however, is conducted blind. Doctors can’t tell how much dialysis a patient needs based on kidney values at the time of treatment, says Meera Harhay, a nephrologist at Drexel University in Philadelphia.

But it’s the impact of dialysis on their day-to-day lives that creates the most problems for patients. Only one-quarter of those on dialysis are able to remain employed (compared to 85% of similar-aged adults), and many report a low quality of life. Having more flexibility in life would make a major different to her patients, Harhay says.

“Almost half their week is taken up by the burden of their treatment. It really eats away at their freedom and their ability to do things that add value to their life,” she says.

Art imitates life

The challenge for artificial kidney designers was how to compress the kidney’s natural functions into a portable, wearable, or implantable device that wouldn’t need constant access to gallons of purified and sterilized water. The other universal challenge they faced was ensuring that any part of the artificial kidney that would come in contact with blood was kept germ-free to prevent infection.

As part of the 2021 KidneyX Prize, a partnership between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the American Society of Nephrology, inventors were challenged to create prototypes for artificial kidneys. Himmelfarb’s team at the University of Washington’s Center for Dialysis Innovation won the prize by focusing on miniaturizing existing technologies to create a portable dialysis machine. The backpack sized AKTIV device (Ambulatory Kidney to Increase Vitality) will recycle dialysate in a closed loop system that removes urea from blood and uses light-based chemical reactions to convert the urea to nitrogen and carbon dioxide, which allows the dialysate to be recirculated.

Himmelfarb says that the AKTIV can be used when at home, work, or traveling, which will give users more flexibility and freedom. “If you had a 30-pound device that you could put in the overhead bins when traveling, you could go visit your grandkids,” he says.

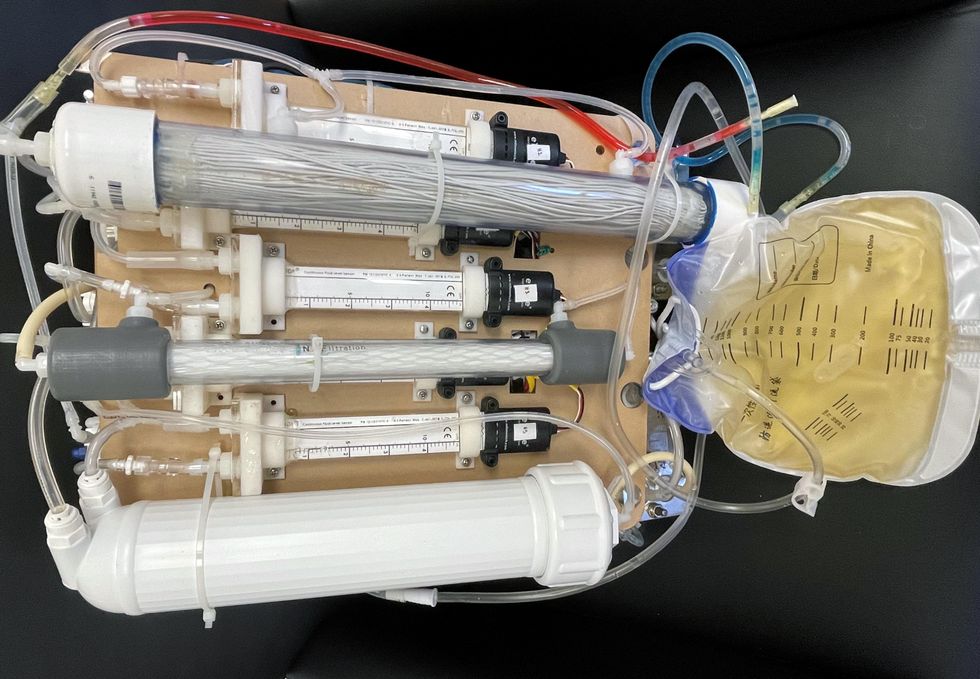

Kurtz’s team at UCLA partnered with the U.S. Kidney Research Corporation and Arkansas University to develop a dialysate-free desktop device (about the size of a small printer) as the first phase of a progression that will he hopes will lead to something small and implantable. Part of the reason for the artificial kidney’s size, Kurtz says, is the number of functions his team are cramming into it. Not only will it filter urea from blood, but it will also use electricity to help regulate electrolyte levels in a process called electrodeionization. Kurtz emphasizes that these additional functions are what makes his design a true artificial kidney instead of just a small dialysis machine.

One version of an artificial kidney.

UCLA

“It doesn't have just a static function. It has a bank of sensors that measure chemicals in the blood and feeds that information back to the device,” Kurtz says.

Other startups are getting in on the game. Nephria Bio, a spinout from the South Korean-based EOFlow, is working to develop a wearable dialysis device, akin to an insulin pump, that uses miniature cartridges with nanomaterial filters to clean blood (Harhay is a scientific advisor to Nephria). Ian Welsford, Nephria’s co-founder and CTO, says that the device’s design means that it can also be used to treat acute kidney injuries in resource-limited settings. These potentials have garnered interest and investment in artificial kidneys from the U.S. Department of Defense.

For his part, Burton is most interested in an implantable device, as that would give him the most freedom. Even having a regular outpatient procedure to change batteries or filters would be a minor inconvenience to him.

“Being plugged into a machine, that’s not mimicking life,” he says.

This article was first published by Leaps.org on May 5, 2022.