Alzheimer’s prevention may be less about new drugs, more about income, zip code and education

(Left to right) Vickie Naylor, Bernadine Clay, and Donna Maxey read a memory prompt as they take part in the Sharing History through Active Reminiscence and Photo-Imagery (SHARP) study, September 20, 2017.

That your risk of Alzheimer’s disease depends on your salary, what you ate as a child, or the block where you live may seem implausible. But researchers are discovering that social determinants of health (SDOH) play an outsized role in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, possibly more than age, and new strategies are emerging for how to address these factors.

At the 2022 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, a series of presentations offered evidence that a string of socioeconomic factors—such as employment status, social support networks, education and home ownership—significantly affected dementia risk, even when adjusting data for genetic risk. What’s more, memory declined more rapidly in people who earned lower wages and slower in people who had parents of higher socioeconomic status.

In 2020, a first-of-its kind study in JAMA linked Alzheimer’s incidence to “neighborhood disadvantage,” which is based on SDOH indicators. Through autopsies, researchers analyzed brain tissue markers related to Alzheimer’s and found an association with these indicators. In 2022, Ryan Powell, the lead author of that study, published further findings that neighborhood disadvantage was connected with having more neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques, the main pathological features of Alzheimer's disease.

As of yet, little is known about the biological processes behind this, says Powell, director of data science at the Center for Health Disparities Research at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. “We know the association but not the direct causal pathway.”

The corroborative findings keep coming. In a Nature study published a few months after Powell’s study, every social determinant investigated affected Alzheimer’s risk except for marital status. The links were highest for income, education, and occupational status.

Clinical trials on new Alzheimer’s medications get all the headlines but preventing dementia through policy and public health interventions should not be underestimated.

The potential for prevention is significant. One in three older adults dies with Alzheimer's or another dementia—more than breast and prostate cancers combined. Further, a 2020 report from the Lancet Commission determined that about 40 percent of dementia cases could theoretically be prevented or delayed by managing the risk factors that people can modify.

Take inactivity. Older adults who took 9,800 steps daily were half as likely to develop dementia over the next 7 years, in a 2022 JAMA study. Hearing loss, another risk factor that can be managed, accounts for about 9 percent of dementia cases.

Clinical trials on new Alzheimer’s medications get all the headlines but preventing dementia through policy and public health interventions should not be underestimated. Simply slowing the course of Alzheimer’s or delaying its onset by five years would cut the incidence in half, according to the Global Council on Brain Health.

Minorities Hit the Hardest

The World Health Organization defines SDOH as “conditions in which people are born, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.”

Anyone who exists on processed food, smokes cigarettes, or skimps on sleep has heightened risks for dementia. But minority groups get hit harder. Older Black Americans are twice as likely to have Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia as white Americans; older Hispanics are about one and a half times more likely.

This is due in part to higher rates of diabetes, obesity, and high blood pressure within these communities. These diseases are linked to Alzheimer’s, and SDOH factors multiply the risks. Blacks and Hispanics earn less income on average than white people. This means they are more likely to live in neighborhoods with limited access to healthy food, medical care, and good schools, and suffer greater exposure to noise (which impairs hearing) and air pollution—additional risk factors for dementia.

Related Reading: The Toxic Effects of Noise and What We're Not Doing About it

Plus, when Black people are diagnosed with dementia, their cognitive impairment and neuropsychiatric symptom are more advanced than in white patients. Why? Some African-Americans delay seeing a doctor because of perceived discrimination and a sense they will not be heard, says Carl V. Hill, chief diversity, equity, and inclusion officer at the Alzheimer’s Association.

Misinformation about dementia is another issue in Black communities. The thinking is that Alzheimer’s is genetic or age-related, not realizing that diet and physical activity can improve brain health, Hill says.

African Americans are severely underrepresented in clinical trials for Alzheimer’s, too. So, researchers miss the opportunity to learn more about health disparities. “It’s a bioethical issue,” Hill says. “The people most likely to have Alzheimer’s aren’t included in the trials.”

The Cure: Systemic Change

People think of lifestyle as a choice but there are limitations, says Muniza Anum Majoka, a geriatric psychiatrist and assistant professor of psychiatry at Yale University, who published an overview of SDOH factors that impact dementia. “For a lot of people, those choices [to improve brain health] are not available,” she says. If you don’t live in a safe neighborhood, for example, walking for exercise is not an option.

Hill wants to see the focus of prevention shift from individual behavior change to ensuring everyone has access to the same resources. Advice about healthy eating only goes so far if someone lives in a food desert. Systemic change also means increasing the number of minority physicians and recruiting minorities in clinical drug trials so studies will be relevant to these communities, Hill says.

Based on SDOH impact research, raising education levels has the most potential to prevent dementia. One theory is that highly educated people have a greater brain reserve that enables them to tolerate pathological changes in the brain, thus delaying dementia, says Majoka. Being curious, learning new things and problem-solving also contribute to brain health, she adds. Plus, having more education may be associated with higher socioeconomic status, more access to accurate information and healthier lifestyle choices.

New Strategies

The chasm between what researchers know about brain health and how the knowledge is being applied is huge. “There’s an explosion of interest in this area. We’re just in the first steps,” says Powell. One day, he predicts that physicians will manage Alzheimer’s through precision medicine customized to the patient’s specific risk factors and needs.

Raina Croff, assistant professor of neurology at Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine, created the SHARP (Sharing History through Active Reminiscence and Photo-imagery) walking program to forestall memory loss in African Americans with mild cognitive impairment or early dementia.

Participants and their caregivers walk in historically black neighborhoods three times a week over six months. A smart tablet provides information about “Memory Markers” they pass, such as the route of a civil rights march. People celebrate their community and culture while “brain health is running in the background,” Croff says.

Photos and memory prompts engage participants in the SHARP program.

OHSU/Kristyna Wentz-Graff

The project began in 2015 as a pilot study in Croff’s hometown of Portland, Ore., expanded to Seattle, and will soon start in Oakland, Calif. “Walking is good for slowing [brain] decline,” she says. A post-study assessment of 40 participants in 2017 showed that half had higher cognitive scores after the program; 78 percent had lower blood pressure; and 44 percent lost weight. Those with mild cognitive impairment showed the most gains. The walkers also reported improved mood and energy along with increased involvement in other activities.

It’s never too late to reap the benefits of working your brain and being socially engaged, Majoka says.

In Milwaukee, the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Institute launched the The Amazing Grace Chorus® to stave off cognitive decline in seniors. People in early stages of Alzheimer’s practice and perform six concerts each year. The activity provides opportunities for social engagement, mental stimulation, and a support network. Among the benefits, 55 percent reported better communication at home and nearly half of participants said they got involved with more activities after participating in the chorus.

Private companies are offering intervention services to healthcare providers and insurers to manage SDOH, too. One such service, MyHello, makes calls to at-risk people to assess their needs—be it food, transportation or simply a friendly voice. Having a social support network is critical for seniors, says Majoka, noting there was a steep decline in cognitive function among isolated elders during Covid lockdowns.

About 1 in 9 Americans age 65 or older live with Alzheimer’s today. With a surge in people with the disease predicted, public health professionals have to think more broadly about resource targets and effective intervention points, Powell says.

Beyond breakthrough pills, that is. Like Dorothy in Kansas discovering happiness was always in her own backyard, we are beginning to learn that preventing Alzheimer’s is in our reach if only we recognized it.

A brownie cake and whipped cream beckon on a plate.

Imagine eating a slice of cake for breakfast. It's deliciously indulgent, but instead of your blood sugar spiking, your body processes all that sweetness as a healthy high-protein meal. It may sound like sci-fi, but this scenario is not necessarily far off.

"People with diabetes could especially benefit because sweet proteins don't trigger a need for insulin."

The Lowdown

An award-winning agtech startup called Amai is developing "sweet proteins," based on the molecular structure of naturally occuring exotic fruits. These new sugar substitutes could potentially replace artificial sweeteners and help people who are trying to curb their sugar intake. People with diabetes could especially benefit because sweet proteins don't trigger a need for insulin.

While there is a sweet protein currently on the market today called thaumatin, it's expensive, has a short shelf life, and is lacking in the taste department. But Amai's proteins taste 70 to 100 percent identical to the sweet ones found in nature. Once their molecular structure is designed through a sophisticated computing platform, they are made through fermentation, which is akin to brewing beer. These non-GMO proteins are over 10,000 times sweeter than sugar, which means much less needs to be produced and used.

Diseases like diabetes and heart disease, which are often linked to sugar overconsumption, have been on a major upswing over the last few decades, especially in the United States. According to the CDC, 100 million adults in the United States are now living with diabetes or prediabetes, which if not treated, often leads to type 2 diabetes within five years. By 2030, scientists predict cases of diabetes in the U.S. will increase by 54 percent. If sugar proteins like the type Amai is creating become widely available, these numbers could begin to decrease.

Next Up

Amai's sweet proteins are still in the research and development stage, but the Israeli startup is raising significant funding that should help expedite the process. They're also substantially upping their production ability by expanding their facilities.

Will consumers be comfortable ingesting a lab-designed food product?

And in March, the USDA and FDA announced plans to regulate cell-cultured foods, the category in which these sugar proteins would fall, so Amai researchers are hopeful they'll have an easier path to approval once their product is market ready.

Open Questions

All this progress may sound promising, but Amai still has a long way to go before the reality of healthy cake becomes tangible. Some questions to consider: Will consumers be comfortable ingesting a lab-designed food product? Will it taste enough like real sugar?

And if some products and brands begin to adopt it, will it ever overtake the real thing in popularity and make a dent in diseases like diabetes and obesity? Only time, more research, and a lot more money will tell, but in the meantime, feel free to daydream about eating entire pints of ice cream without needing to hit the gym.

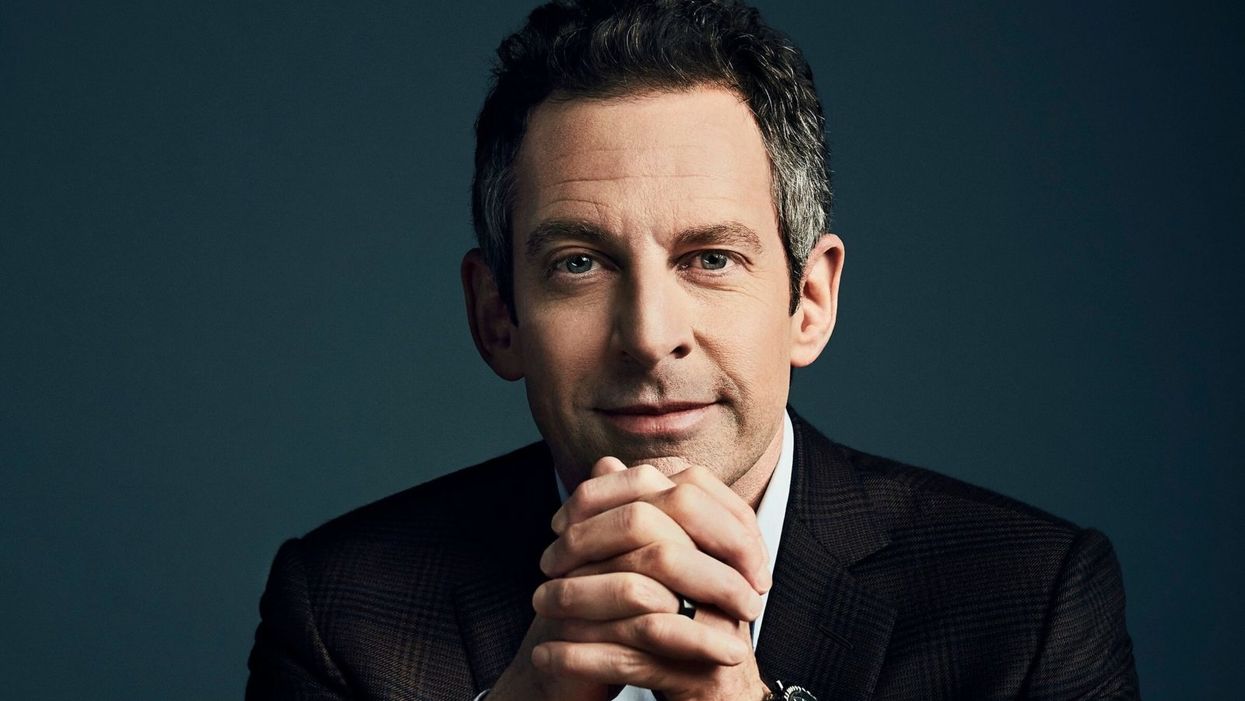

One of the World’s Most Famous Neuroscientists Wants You to Embrace Meditation and Spirituality

Sam Harris, the neuroscientist and bestselling author, discusses mindfulness meditation.

Neuroscientist, philosopher, and bestselling author Sam Harris is famous for many reasons, among them his vocal criticism of religion, his scientific approach to moral questions, and his willingness to tackle controversial topics on his popular podcast.

"Until you have some capacity to be mindful, you have no choice but to be lost in every next thought that arises."

He is also a passionate advocate of mindfulness meditation, having spent formative time as a young adult learning from teachers in India and Tibet before returning to the West.

Now his new app called Waking Up aims to teach the principles of meditation to anyone who is willing to slow down, turn away from everyday distractions, and pay attention to their own mind. Harris recently chatted with leapsmag about the science of mindfulness, the surprising way he discovered it, and the fundamental—but under-appreciated—reason to do it. This conversation has been lightly edited and condensed.

One of the biggest struggles that so many people face today is how to stay present in the moment. Is this the default state for human beings, or is this a more recent phenomenon brought on by our collective addiction to screens?

Sam: No, it certainly predates our technology. This is something that yogis have been talking about and struggling with for thousands of years. Just imagine you're on a beach on vacation where you vowed not to pick up your smart phone for 24 hours. You haven't looked at a screen, you're just enjoying the sound of the waves and the sunset, or trying to. What you're competing with there is this incessant white noise of discursive thinking. And that's something that follows you everywhere. It's something that people tend to only become truly sensitive to once they try to learn to meditate.

You've mentioned in one of your lessons that the more you train in mindful meditation, the more freedom you will have. What do you mean?

Sam: Well, until you have some capacity to be mindful, you have no choice but to be lost in every next thought that arises. You can't notice thought as thought, it just feels like you. So therefore, you're hostage to whatever the emotional or behavioral consequences of those thoughts are. If they're angry thoughts, you're angry. If they're desire thoughts, you're filled with desire. There is very little understanding in Western psychology around an alternative to that. And it's only by importing mindfulness into our thinking that we have begun to dimly see an alternative.

You've said that even if there were no demonstrable health benefits, it would still be valuable to meditate. Why?

Sam: Yeah, people are putting a lot of weight on the demonstrated health and efficiency benefits of mindfulness. I don't doubt that they exist, I think some of the research attesting to them is pretty thin, but it just may in fact be the case that meditation improves your immune system, and staves off dementia, or the thinning of the cortex as we age and many other benefits.

"What was Jesus talking about? Well, he certainly seemed to be talking about a state of mind that I first discovered on MDMA."

[But] it trivializes the real power of the practice. The power of the practice is to discover something fundamental about the nature of consciousness that can liberate you from psychological suffering in each moment that you can be aware of it. And that's a fairly esoteric goal and concern, it's an ancient one. It is something more than a narrow focus on physical health or even the ordinary expectations of well-being.

Yet many scientists in the West and intellectuals, like Richard Dawkins, are skeptical of it. Would you support a double-blind placebo-controlled study of meditation or does that miss the deeper point?

Sam: No, I see value in studying it any way we can. It's a little hard to pick a control condition that really makes sense. But yeah, that's research that I'm actually collaborating in now. There's a team just beginning a study of my app and we're having to pick a control condition. You can't do a true double-blind placebo control because meditation is not a pill, it's a practice. You know what you're being told to do. And if you're being told that you're in the control condition, you might be told to just keep a journal, say, of everything that happened to you yesterday.

One way to look at it is just to take people who haven't done any significant practice and to have them start and compare them to themselves over time using each person as his own control. But there are limitations with that as well. So, it's a little hard to study, but it's certainly not impossible.

And again, the purpose of meditation is not merely to reduce stress or to improve a person's health. And there are certain aspects to it which don't in any linear way reduce stress. You can have stressful experiences as you begin to learn to be mindful. You become more aware of your own neuroses certainly in the beginning, and you become more aware of your capacity to be petty and deceptive and self-deceptive. There are unflattering things to be realized about the character of your own mind. And the question is, "Is there a benefit ultimately to realizing those things?" I think there clearly is.

I'm curious about your background. You left Stanford to practice meditation after an experience with the drug MDMA. How did that lead you to meditation?

Sam: The experience there was that I had a feeling -- what I would consider unconditional love -- for the first time. Whether I ever had the concept of unconditional love in my head at that point, I don't know, I was 18 and not at all religious. But it was an experience that certainly made sense of the kind of language you find in many spiritual traditions, not just what it's like to be fully actualized by those, by, let's say, Christian values. Like, what was Jesus talking about? Well, he certainly seemed to be talking about a state of mind that I first discovered on MDMA. So that led me to religious literature, spiritual or new age literature, and Eastern philosophy.

Looking to make sense of this and put into a larger context that wasn't just synonymous with taking drugs, it was a sketching a path of practice and growth that could lead further across this landscape of mind, which I just had no idea existed. I basically thought you have whatever mind you have, and the prospect of having a radically different experience of consciousness, that would just be a fool's errand, and anyone who claimed to have such an experience would probably be lying.

As you probably know, there's a resurgence of research in psychedelics now, which again I also fully support, and I've had many useful experiences since that first one, on LSD and psilocybin. I don't tend to take those drugs now; it's been many years since I've done anything significant in that area, but the utility is that they work for everyone, more or less, which is to say that they prove beyond any doubt to everyone that it's possible to have a very different experience of consciousness moment to moment. Now, you can have scary experiences on some of these drugs, and I don't recommend them for everybody, but the one thing you can't have is the experience of boredom. [chuckle]

Very true. Going back to your experiences, you've done silent meditation for 18 hours a day with monks abroad. Do you think that kind of immersive commitment is an ideal goal, or is there a point where too much meditation is counter-productive to a full life?

Sam: I think all of those possibilities are true, depending on the person. There are people who can't figure out how to live a satisfying life in the world, and they retreat as a way of trying to untie the knot of their unhappiness directly through practice.

But the flip side is also true, that in order to really learn this skill deeply, most people need some kind of full immersion experience, at least at some point, to break through to a level of familiarity with it that would be very hard to get for most people practicing for 10 minutes a day, or an hour a day. But ultimately, I think it is a matter of practicing for short periods, frequently, more than it's a matter of long hours in one's daily life. If you could practice for one minute, 100 times a day, that would be an extraordinarily positive way to punctuate your habitual distraction. And I think probably better than 100 minutes all in one go first thing in the morning.

"It's amazing to me to walk into a classroom where you see 15 or 20 six-year-olds sitting in silence for 10 or 15 minutes."

What's your daily meditation practice like today? How does it fit into your routine?

Sam: It's super variable. There are days where I don't find any time to practice formally, there are days where it's very brief, and there are days where I'll set aside a half hour. I have young kids who I don't feel like leaving to go on retreat just yet, but I'm sure retreat will be a part of my future as well. It's definitely useful to just drop everything and give yourself permission to not think about anything for a certain period. And you're left with this extraordinarily vivid confrontation with your default state, which is your thoughts are incessantly appearing and capturing your attention and deluding you.

Every time you're lost in thought, you're very likely telling yourself a story for the 15th time that you don't even have the decency to find boring, right? Just imagine what it would sound like if you could broadcast your thoughts on a loud speaker, it would be mortifying. These are desperately boring, repetitive rehearsals of past conversations and anxieties about the future and meaningless judgments and observations. And in each moment that we don't notice a thought as a thought, we are deluded about what has happened. It's created this feeling of self that is a misconstrual of what consciousness is actually like, and it's created in most cases a kind of emotional emergency, which is our lives and all of the things we're worrying about. But our worry adds absolutely nothing to our capacity to deal with the problems when they actually arise.

Right. You mentioned you're a parent of a young kid, and so am I. Is there anything we as parents can do to encourage a mindfulness habit when our kids are young?

Sam: Actually, we just added meditations for kids in the app. My wife, Annaka, teaches meditation to kids as young as five in school. And they can absolutely learn to be mindful, even at that age. And it's amazing to me to walk into a classroom where you see 15 or 20 six-year-olds sitting in silence for 10 or 15 minutes, it's just amazing. And that's not what happens on the first day, but after five or six classes that is what happens. For a six-year-old to become aware of their emotional life in a clear way and to recognize that he was sad, or angry…that's a kind of super power. And it becomes a basis of any further capacity to regulate emotion and behavior.

It can be something that they're explicitly taught early and it can be something that they get modeled by us. They can know that we practice. You can just sit with your kid when your kid is playing. Just a few minutes goes a long way. You model this behavior and punctuate your own distraction for a short period of time, and it can be incredibly positive.

Lastly, a bonus question that is definitely tongue-in-cheek. Who would win in a fight, you or Ben Affleck?

Sam: That's funny. That question was almost resolved in the green room after that encounter. That was an unpleasant meeting…I spend some amount of time training in the martial arts. This is one area where knowledge does count for a lot, but I don't think we'll have to resolve that uncertainty any time soon. We're both getting old.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.