Trading syphilis for malaria: How doctors treated one deadly disease by infecting patients with another

In the 1920s, doctors induced a high fever in patients - so called "fever therapy" - as a way to help them recover from syphilis, though it involved ethical problems.

If you had lived one hundred years ago, syphilis – a bacterial infection spread by sexual contact – would likely have been one of your worst nightmares. Even though syphilis still exists, it can now be detected early and cured quickly with a course of antibiotics. Back then, however, before antibiotics and without an easy way to detect the disease, syphilis was very often a death sentence.

To understand how feared syphilis once was, it’s important to understand exactly what it does if it’s allowed to progress: the infections start off as small, painless sores or even a single sore near the vagina, penis, anus, or mouth. The sores disappear around three to six weeks after the initial infection – but untreated, syphilis moves into a secondary stage, often presenting as a mild rash in various areas of the body (such as the palms of a person’s hands) or through other minor symptoms. The disease progresses from there, often quietly and without noticeable symptoms, sometimes for decades before it reaches its final stages, where it can cause blindness, organ damage, and even dementia. Research indicates, in fact, that as much as 10 percent of psychiatric admissions in the early 20th century were due to dementia caused by syphilis, also known as neurosyphilis.

Like any bacterial disease, syphilis can affect kids, too. Though it’s spread primarily through sexual contact, it can also be transmitted from mother to child during birth, causing lifelong disability.

The poet-physician Aldabert Bettman, who wrote fictionalized poems based on his experiences as a doctor in the 1930s, described the effect syphilis could have on an infant in his poem Daniel Healy:

I always got away clean

when I went out

With the boys.

The night before

I was married

I went out,—But was not so fortunate;

And I infected

My bride.

When little Daniel

Was born

His eyes discharged;

And I dared not tell

That because

I had seen too much

Little Daniel sees not at all

Given the horrors of untreated syphilis, it’s maybe not surprising that people would go to extremes to try and treat it. One of the earliest remedies for syphilis, dating back to 15th century Naples, was using mercury – either rubbing it on the skin where blisters appeared, or breathing it in as a vapor. (Not surprisingly, many people who underwent this type of “treatment” died of mercury poisoning.)

Other primitive treatments included using tinctures made of a flowering plant called guaiacum, as well as inducing “sweat baths” to eliminate the syphilitic toxins. In 1910, an arsenic-based drug called Salvarsan hit the market and was hailed as a “magic bullet” for its ability to target and destroy the syphilis-causing bacteria without harming the patient. However, while Salvarsan was effective in treating early-stage syphilis, it was largely ineffective by the time the infection progressed beyond the second stage. Tens of thousands of people each year continued to die of syphilis or were otherwise shipped off to psychiatric wards due to neurosyphilis.

It was in one of these psychiatric units in the early 20th century that Dr. Julius Wagner-Juaregg got the idea for a potential cure.

Wagner-Juaregg was an Austrian-born physician trained in “experimental pathology” at the University of Vienna. Wagner-Juaregg started his medical career conducting lab experiments on animals and then moved on to work at different psychiatric clinics in Vienna, despite having no training in psychiatry or neurology.

Wagner-Juaregg’s work was controversial to say the least. At the time, medicine – particularly psychiatric medicine – did not have anywhere near the same rigorous ethical standards that doctors, researchers, and other scientists are bound to today. Wagner-Juaregg would devise wild theories about the cause of their psychiatric ailments and then perform experimental procedures in an attempt to cure them. (As just one example, Wagner-Juaregg would sterilize his adolescent male patients, thinking “excessive masturbation” was the cause of their schizophrenia.)

But sometimes these wild theories paid off. In 1883, during his residency, Wagner-Juaregg noted that a female patient with mental illness who had contracted a skin infection and suffered a high fever experienced a sudden (and seemingly miraculous) remission from her psychosis symptoms after the fever had cleared. Wagner-Juaregg theorized that inducing a high fever in his patients with neurosyphilis could help them recover as well.

Eventually, Wagner-Juaregg was able to put his theory to the test. Around 1890, Wagner-Juaregg got his hands on something called tuberculin, a therapeutic treatment created by the German microbiologist Robert Koch in order to cure tuberculosis. Tuberculin would later turn out to be completely ineffective for treating tuberculosis, often creating severe immune responses in patients – but for a short time, Wagner-Juaregg had some success in using tuberculin to help his dementia patients. Giving his patients tuberculin resulted in a high fever – and after completing the treatment, Wagner-Jauregg reported that his patient’s dementia was completely halted. The success was short-lived, however: Wagner-Juaregg eventually had to discontinue tuberculin as a treatment, as it began to be considered too toxic.

By 1917, Wagner-Juaregg’s theory about syphilis and fevers was becoming more credible – and one day a new opportunity presented itself when a wounded soldier, stricken with malaria and a related fever, was accidentally admitted to his psychiatric unit.

When his findings were published in 1918, Wagner-Juaregg’s so-called “fever therapy” swept the globe.

What Wagner-Juaregg did next was ethically deplorable by any standard: Before he allowed the soldier any quinine (the standard treatment for malaria at the time), Wagner-Juaregg took a small sample of the soldier’s blood and inoculated three syphilis patients with the sample, rubbing the blood on their open syphilitic blisters.

It’s unclear how well the malaria treatment worked for those three specific patients – but Wagner-Juaregg’s records show that in the span of one year, he inoculated a total of nine patients with malaria, for the sole purpose of inducing fevers, and six of them made a full recovery. Wagner-Juaregg’s treatment was so successful, in fact, that one of his inoculated patients, an actor who was unable to work due to his dementia, was eventually able to find work again and return to the stage. Two additional patients – a military officer and a clerk – recovered from their once-terminal illnesses and returned to their former careers as well.

When his findings were published in 1918, Wagner-Juaregg’s so-called “fever therapy” swept the globe. The treatment was hailed as a breakthrough – but it still had risks. Malaria itself had a mortality rate of about 15 percent at the time. Many people considered that to be a gamble worth taking, compared to dying a painful, protracted death from syphilis.

Malaria could also be effectively treated much of the time with quinine, whereas other fever-causing illnesses were not so easily treated. Triggering a fever by way of malaria specifically, therefore, became the standard of care.

Tens of thousands of people with syphilitic dementia would go on to be treated with fever therapy until the early 1940s, when a combination of Salvarsan and penicillin caused syphilis infections to decline. Eventually, neurosyphilis became rare, and then nearly unheard of.

Despite his contributions to medicine, it’s important to note that Wagner-Juaregg was most definitely not a person to idolize. In fact, he was an outspoken anti-Semite and proponent of eugenics, arguing that Jews were more prone to mental illness and that people who were mentally ill should be forcibly sterilized. (Wagner-Juaregg later became a Nazi sympathizer during Hitler’s rise to power even though, bizarrely, his first wife was Jewish.) Another problematic issue was that his fever therapy involved experimental treatments on many who, due to their cognitive issues, could not give informed consent.

Lack of consent was also a fundamental problem with the syphilis study at Tuskegee, appalling research that began just 14 years after Wagner-Juaregg published his “fever therapy” findings.

Still, despite his outrageous views, Wagner-Juaregg was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology in 1927 – and despite some egregious human rights abuses, the miraculous “fever therapy” was partly responsible for taming one of the deadliest plagues in human history.

The Nation’s Science and Health Agencies Face a Credibility Crisis: Can Their Reputations Be Restored?

Morale at federal science agencies -- and public trust in their guidance -- is at a concerning low right now.

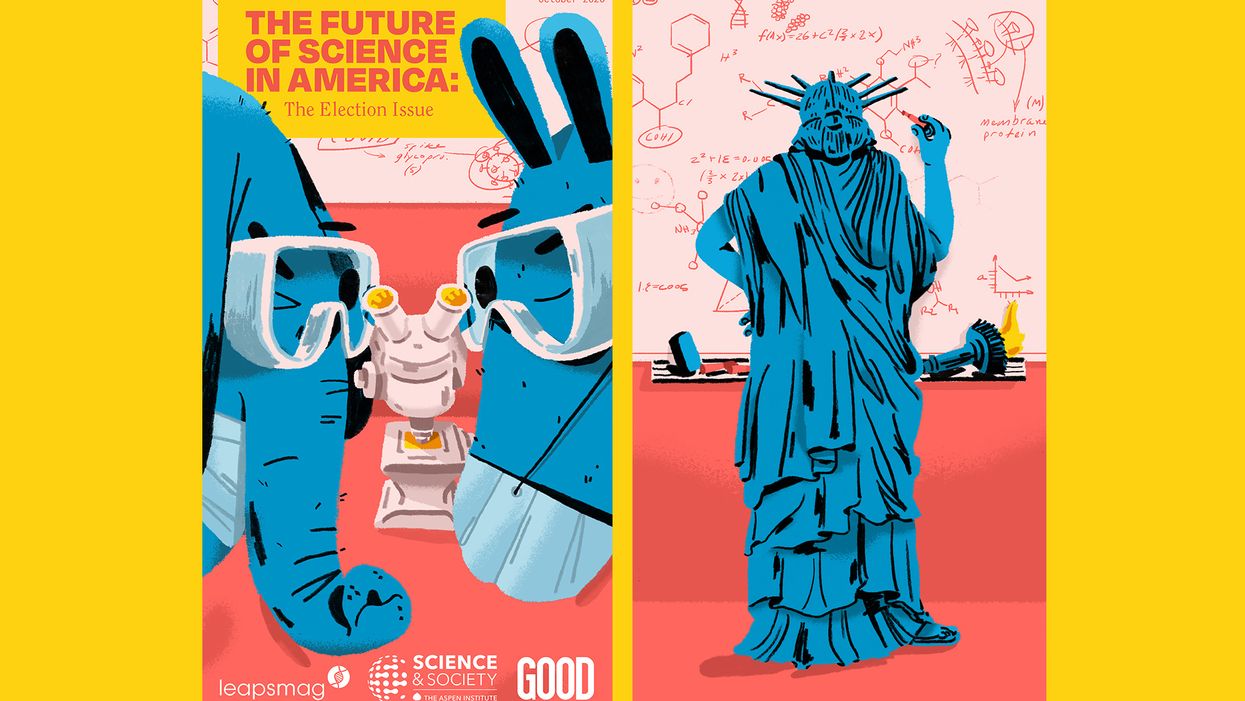

This article is part of the magazine, "The Future of Science In America: The Election Issue," co-published by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD.

It didn't have to be this way. More than 200,000 Americans dead, seven million infected, with numbers continuing to climb, an economy in shambles with millions out of work, hundreds of thousands of small businesses crushed with most of the country still under lockdown. And all with no end in sight. This catastrophic result is due in large part to the willful disregard of scientific evidence and of muzzling policy experts by the Trump White House, which has spent its entire time in office attacking science.

One of the few weapons we had to combat the spread of Covid-19—wearing face masks—has been politicized by the President, who transformed this simple public health precaution into a first amendment issue to rally his base. Dedicated public health officials like Dr. Anthony Fauci, the highly respected director of the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases, have received death threats, which have prompted many of them around the country to resign.

Over the summer, the Trump White House pressured the Centers for Disease Control, which is normally in charge of fighting epidemics, to downplay COVID risks among young people and encourage schools to reopen. And in late September, the CDC was forced to pull federal teams who were going door-to-door doing testing surveys in Minnesota because of multiple incidents of threats and abuse. This list goes on and on.

Still, while the Trump administration's COVID failures are the most visible—and deadly—the nation's entire federal science infrastructure has been undermined in ways large and small.

The White House has steadily slashed monies for science—the 2021 budget cuts funding by 10–30% or more for crucial agencies like National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—and has gutted health and science agencies across the board, including key agencies of the Department of Energy and the Interior, especially in divisions that deal with issues they oppose ideologically like climate change.

Even farmers can't get reliable information about how climate change affects planting seasons because the White House moved the entire staff at the U.S. Department of Agriculture agency who does this research, relocating them from Maryland to Kansas City, Missouri. Many of these scientists couldn't uproot their families and sell their homes, so the division has had to pretty much start over from scratch with a skeleton crew.

More than 1,600 federal scientists left government in the first two years of the Trump Administration, according to data compiled by the Washington Post, and one-fifth of top positions in science are vacant, depriving agencies of the expertise they need to fulfill their vital functions. Industry executives and lobbyists have been installed as gatekeepers—HHS Secretary Alex Azar was previously president of Eli Lilly, and three climate change deniers were appointed to key posts at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, to cite just a couple of examples. Trump-appointed officials have sidelined, bullied, or even vilified those who dare to speak out, which chills the rigorous debate that is the essential to sound, independent science.

"The CDC needs to be able to speak regularly to the American people to explain what it knows and how it knows it."

Linda Birnbaum knows firsthand what it's like to become a target. The microbiologist recently retired after more than a decade as the director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, which is the world's largest environmental health organization and the greatest funder of environmental health and toxicology research, a position that often put her agency at odds with the chemical and fossil fuel industry. There was an attempt to get her fired, she says, "because I had the nerve to write that science should be used in making policy. The chemical industry really went after me, and my last two years were not so much fun under this administration. I'd like to believe it was because I was making a difference—if I wasn't, they wouldn't care."

Little wonder that morale at federal agencies is low. "We're very frustrated," says Dr. William Schaffner, a veteran infectious disease specialist and a professor of medicine at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville. "My colleagues within these agencies, the CDC rank and file, are keeping their heads down doing the best they can, and they hope to weather this storm."

The cruel irony is that the United States was once a beacon of scientific innovation. In the heady post World War II years, while Europe lay in ruins, the successful development of penicillin and the atomic bomb—which Americans believed helped vanquish the Axis powers—unleashed a gusher of public money into research, launching an unprecedented era of achievement in American science. Scientists conquered polio, deciphered the genetic code, harnessed the power of the atom, invented lasers, transistors, microchips and computers, sent missions beyond Mars, and landed men on the moon. A once-inconsequential hygiene laboratory was transformed into the colossus the National Institutes of Health has become, which remains today the world's flagship medical research center, unrivaled in size and scope.

At the same time, a tiny public health agency headquartered in Atlanta, which had been in charge of eradicating the malaria outbreaks that plagued impoverished rural areas in the Deep South until the late 1940s, evolved into the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC became the world's leader in fighting disease outbreaks, and the agency's crack team of epidemiologists—members of the vaunted Epidemic Intelligence Service—were routinely dispatched to battle global outbreaks of contagions such as Ebola and malaria and help lead the vaccination campaigns to eradicate killers like polio and small pox that have saved millions of lives.

What will it take to rebuild our federal science infrastructure and restore not only the public's confidence but the respect of the world's scientific community? There are some hopeful signs that there is pushback against the current national leadership, and non-profit watchdog groups like the Union of Concerned Scientists have mapped out comprehensive game plans to restore public trust and the integrity of science.

These include methods of protecting science from political manipulation; restoring the oversight role of independent federal advisory committees, whose numbers were decimated by recent executive orders; strengthening scientific agencies that have been starved by budget cuts and staff attrition; and supporting whistleblower protections and allowing scientists to do their jobs without political meddling to restore integrity to the process. And this isn't just a problem at the CDC. A survey of 1,600 EPA scientists revealed that more than half had been victims of political interference and were pressured to skew their findings, according to research released in April by the Union of Concerned Scientists.

"Federal agencies are staffed by dedicated professionals," says Andrew Rosenberg, director of the Center for Science and Democracy at the Union of Concerned Scientists and a former fisheries biologist for NOAA. "Their job is not to serve the president but the public interest. Inspector generals are continuing to do what they're supposed to, but their findings are not being adhered to. But they need to hold agencies accountable. If an agency has not met its mission or engaged in misconduct, there needs to be real consequences."

On other fronts, last month nine vaccine makers, including Sanofi, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca, took the unprecedented stop of announcing that their COVID-19 vaccines would be thoroughly vetted before they were released. In their implicit refusal to bow to political pressure from the White House to have a vaccine available before the election, their goal was to restore public confidence in vaccine safety, and ensure that enough Americans would consent to have the shot when it was eventually approved so that we'd reach the long-sought holy grail of herd immunity.

"That's why it's really important that all of the decisions need to be made with complete transparency and not taking shortcuts," says Dr. Tom Frieden, president and CEO of Resolve to Save Lives and former director of the CDC during the H1N1, Ebola, and Zika emergencies. "A vaccine is our most important tool, and we can't break that tool by meddling in the science approval process."

In late September, Senate Democrats introduced a new bill to halt political meddling in public health initiatives by the White House. Called Science and Transparency Over Politics Act (STOP), the legislation would create an independent task force to investigate political interference in the federal response to the coronavirus pandemic. "The Trump administration is still pushing the president's political priorities rather than following the science to defeat this virus," Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer said in a press release.

To effectively bring the pandemic under control and restore public confidence, the CDC must assume the leadership role in fighting COVID-19. During previous outbreaks, the top federal infectious disease specialists like Drs. Fauci and Frieden would have daily press briefings, and these need to resume. "The CDC needs to be able to speak regularly to the American people to explain what it knows and how it knows it," says Frieden, who cautions that a vaccine won't be a magic bullet. "There is no one thing that is going to make this virus go away. We need to continue to limit indoor exposures, wear masks, and do strategic testing, isolation, and quarantine. We need a comprehensive approach, and not just a vaccine."

We must also appoint competent and trustworthy leaders, says Rosenberg of the Union of Concerned Scientists. Top posts in too many science agencies are now filled by former industry executives and lobbyists with a built-in bias, as well as people lacking relevant scientific experience, many of whom were never properly vetted because of the current administration's penchant for bypassing Congress and appointing "acting" officials. "We've got great career people who have hung in, but in so much of the federal government, they just put in 'acting' people," says Linda Birnbaum. "They need to bring in better, qualified senior leadership."

Open positions need to be filled, too. Federal science agencies have been seriously crippled by staffing attrition, and the Trump Administration instituted a hiring freeze when it first came in. Staffing levels remain at least ten percent down from previous levels, says Birnbaum and in many agencies, like the EPA, "everything has come to a screeching halt, making it difficult to get anything done."

But in the meantime, the critical first step may be at the ballot box in November. Even Scientific American, the esteemed consumer science publication, for the first time in its 175-year history felt "compelled" to endorse a presidential candidate, Joe Biden, because of the enormity of the damage they say Donald Trump has inflicted on scientists, their legal protections, and on the federal science agencies.

"If the current administration continues, the national political leadership will be emboldened and will be even more assertive of their executive prerogatives and less concerned about traditional niceties, leading to further erosion of the activities of many federal agencies," says Vanderbilt's William Schaffner. "But the reality is, if the team is losing, you change the coach. Then agencies really have to buckle down because it will take some time to restore their hard-earned reputations."

[Editor's Note: To read other articles in this special magazine issue, visit the beautifully designed e-reader version.]

Announcing "The Future of Science in America: The Election Issue"

This special magazine explores what's at stake for science & policy over the next four years.

As reviewed in The Washington Post, "Tomorrow's challenges in science and politics: Magazine offers in-depth takes on these U.S. issues":

"Is it time for a new way to help make adults more science-literate? What should the next president know about science? Could science help strengthen American democracy? "The Future of Science in America: The Election Issue" has answers. The free, online magazine is packed with interesting takes on how science can serve the common good. And just in time. This year has challenged leaders, researchers and the public with thorny scientific questions, from the coronavirus pandemic to widespread misinformation on scientific issues. The magazine is a collaboration of the Aspen Institute, a think tank that brings together a variety of public figures and private individuals to tackle thorny social issues, the digital science magazine Leapsmag and GOOD, a social impact company. It's packed with 15 in-depth articles about science with a view toward our campaign year."

The Future of Science in America: The Election Issue offers wide-ranging perspectives on challenges and opportunities for science as we elect our next national and local leaders. The fast-striking COVID-19 pandemic and the more slowly moving pandemic of climate change have brought into sharp focus how reliant we will be on science and public policy to work together to rescue us from crisis. Doing so will require cooperation between both political parties, as well as significant public trust in science as a beacon to light the path forward.

In spite of its unfortunate emergence as a flash point between two warring parties, we believe that science is the driving force for universal progress. No endeavor is more noble than the quest to rigorously understand our world and apply that knowledge to further human flourishing. This magazine aspires to promote roadmaps for science as a tool for health, a vehicle for progress, and a unifier of our nation.

This special issue is a collaboration among LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD, with support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Rita Allen Foundation.

It is available as a free, beautifully designed digital magazine for both desktop and mobile.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

- SCIENTISTS:

Award-Winning Scientists Offer Advice to the Next President of the United States - PUBLIC OPINION:

National Survey Reveals Americans' Most Important Scientific Priorities - GOVERNMENT:

The Nation's Science and Health Agencies Face a Credibility Crisis: Can Their Reputations Be Restored? - TELEVISION:

To Make Science Engaging, We Need a Sesame Street for Adults - IMMIGRATION:

Immigrant Scientists—and America's Edge—Face a Moment of Truth This Election - RACIAL JUSTICE:

Democratize the White Coat by Honoring Black, Indigenous, and People of Color in Science - EDUCATION:

I'm a Black, Genderqueer Medical Student: Here's My Hard-Won Wisdom for Students and Educational Institutions - TECHNOLOGY:

"Deep Fake" Video Technology Is Advancing Faster Than Our Policies Can Keep Up - VOTERS:

Mind the (Vote) Gap: Can We Get More STEM Students to the Polls? - EXPERTS:

Who Qualifies as an "Expert" and How Can We Decide Who Is Trustworthy? - SOCIAL MEDIA:

Why Your Brain Falls for Misinformation—And How to Avoid It - YOUTH:

Youth Climate Activists Expand Their Focus and Collaborate to Get Out the Vote - SUPREME COURT:

Abortions Before Fetal Viability Are Legal: Might Science and a Change on the Supreme Court Undermine That? - NAVAJO NATION:

An Environmental Scientist and an Educator Highlight Navajo Efforts to Balance Tradition with Scientific Priorities - CIVIC SCIENCE:

Want to Strengthen American Democracy? The Science of Collaboration Can Help

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.