With Mentors, Models, and #MeToo, Femtech Comes of Age

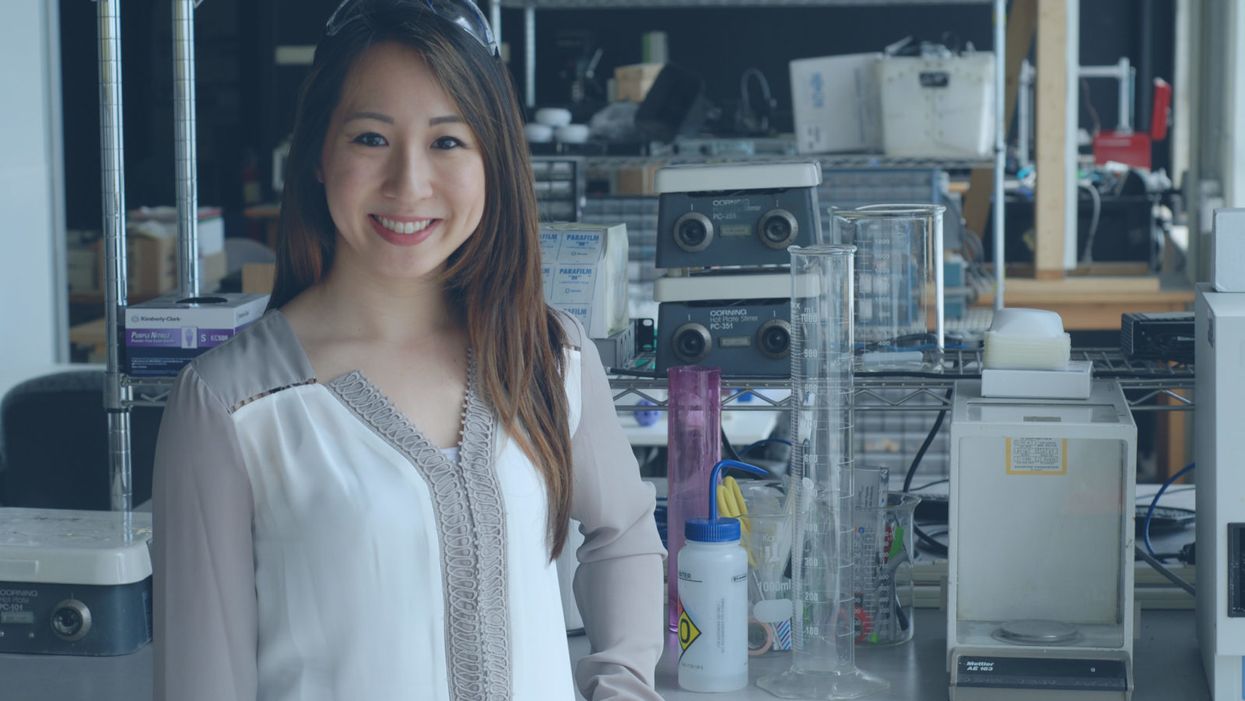

Femtech entrepreneur Stacy Chin attributes her success to backing by mentors and learning how to navigate conversations about personal products in a businesslike manner.

In her quest to become a tech entrepreneur, Stacy Chin has been an ace at tackling thorny intellectual challenges, mastering everything from molecules to manufacturing.

These mostly female leaders of firms with products addressing women's health concerns are winning in a big way, raising about $1.1 billion in startup funds over the past few years.

But the 28-year-old founder of HydroGlyde Coatings, based in Worcester, Mass., admitted to being momentarily stumped recently when pitching her product – a new kind of self-lubricating condom – to venture capitalists.

"Being a young female scientist and going into that sexual healthcare space, it was definitely a little bit challenging to learn how to navigate during presentations and pitches when there were a lot of older males in the audience," said Chin, whose product is of special appeal to older women suffering from vaginal dryness. "I eventually figured it out, but it wasn't easy."

Chin is at the vanguard of a new generation of "femtech" entrepreneurs heading companies with names like LOLA Tampons, Prelude Fertility, and Peach, bringing once-taboo topics like menstruation, ovulation, incontinence, breastfeeding, pelvic pain and, yes, female sexual pleasure to the highest chambers of finance. These mostly female leaders of firms with products addressing women's health concerns are winning in a big way, raising about $1.1 billion in startup funds over the past few years, according to the New York data analytics firm CB Insights.

"We are definitely at a watershed moment for femtech. But we need to remember that [it's] an overnight sensation that is decades in the making."

If the question is "Why now?", the answer may be that femtech leaders are benefiting from the current conversations around respect for women in the workplace, and long-term efforts to achieve gender equality in the male-dominated tech industry.

"We are definitely at a watershed moment for femtech," said Rachel Braun Scherl, a self-described "vaginepreneur" whose new book, "Orgasmic Leadership," profiles femtech leaders. "But we need to remember that femtech is an overnight sensation that is decades in the making."

In contrast with earlier and perhaps less successful generations of women in tech, these pioneers can point to mentors who are readily accessible, as well as more female VC and corporate heads they can directly address when making pitches. There's also a changing cultural landscape where sexual harassment is in the news and women who talk openly about sex in a business context can be taken seriously.

"Change is definitely in the air," said Kevin O'Sullivan, the president and CEO of Massachusetts Biomedical Initiatives, who sponsored Chin and has helped launch more than a hundred biotech companies in his home state since the 1980s.

Like a pinprick bursting a balloon, the #MeToo social movement and its focus on the prevalence of sexual harassment and assault is a factor in the success of femtech, some experts believe, provoking heightened awareness about the role of women in society -- including equal access to start-up capital.

"If such a difficult topic is being discussed in the open, that means more and more people are speaking out and are no longer afraid about sharing their own concerns," said Debbie Hart, president and CEO of BioNJ, a business trade group she founded in 1994. "That's empowering the whole women's movement."

The power of programs that allow young women to witness successful older women in leadership cannot be overstated.

Observers like Hart say that femtech's advent is also due to a payoff from longer-term investments in a slew of programs encouraging girls to pursue STEM careers and women to be hired as leaders, as well as changing social norms to allow female health to be part of the public discourse.

The power of programs that allow young women to witness successful older women in leadership cannot be overstated, according to Susan Scherreik of the Stillman School of Business at Seton Hall University in New Jersey.

"What I have found in entrepreneurship is that it's all about two things: role models and mentoring," said Scherreik, director of the university's Center for Entrepreneurial Studies.

One of Scherreik's top students, Madison Schott, is convinced that the availability of female mentors has been instrumental to her success and will remain so in her future. "It definitely is very encouraging," said Schott, who won the "Pirates Pitch" university-wide business start-up competition in April for an app she is developing that uses AI to guide readers to reliable news sources. "Woman to woman," she added, "you can be more open when you have questions or problems."

Programs that showcase successful females in leadership positions are beginning to bear fruit, inspiring a new generation of females in business, according to Susan Scherreik (at left), director of Seton Hall University's Center for Entrepreneurial Studies at the Stillman School of Business. Her student, Madison Schott (right), is the winner of a university-wide business start-up competition for an app she is developing.

While femtech entrepreneurs may be the beneficiaries of change, they also may be its agents. Scherl, the author, who has been working in the female healthcare sector for more than a decade, believes in persistence. In 2010, organizers of a major awards show banned a product she was marketing, Zestra Essential Arousal Oils*, from a gift bag for honorees. Two years ago, however, times changed and femtech prevailed. The company making goodie bags for Academy Awards nominees included another one of her products, Nuelle's Fiera, a $250 vibrator.

"We come from so many different perspectives when it comes to sex, whether it is cultural, religious, age-related, or even from a trauma, so we never have created a common language," Scherl said. "But we in femtech are making huge progress. We are not only selling products now, we are selling conversation, and we are selling a comfort with sexuality in all its complex forms."

[*Correction: Due to a reporting error, the product that was banned in 2010 was initially identified as Nuelle's Fiera, not Zestra Essential Arousal Oils. The article has been updated for accuracy. --Editor]

This App Helps Diagnose Rare Genetic Disorders from a Picture

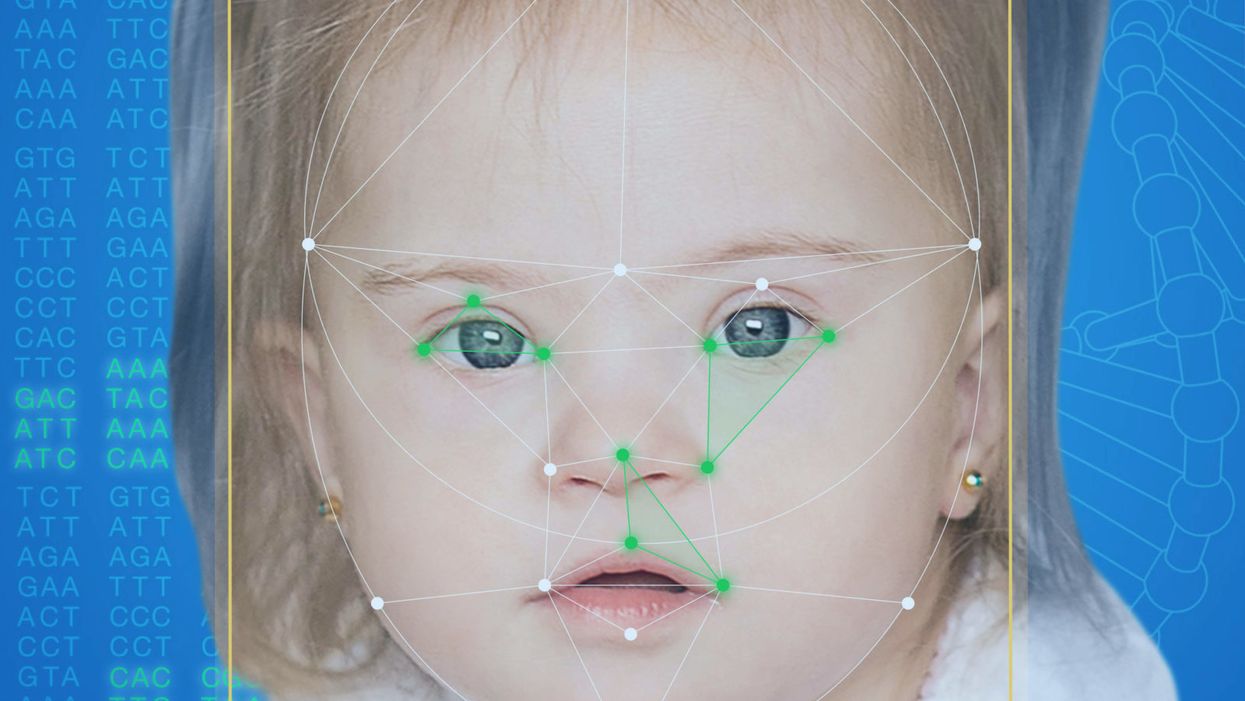

FDNA's Face2Gene technology analyzes patient biometric data using artificial intelligence, identifying correlations with disease-causing genetic variations.

Medical geneticist Omar Abdul-Rahman had a hunch. He thought that the three-year-old boy with deep-set eyes, a rounded nose, and uplifted earlobes might have Mowat-Wilson syndrome, but he'd never seen a patient with the rare disorder before.

"If it weren't for the app I'm not sure I would have had the confidence to say 'yes you should spend $1000 on this test."

Rahman had already ordered genetic tests for three different conditions without any luck, and he didn't want to cost the family any more money—or hope—if he wasn't sure of the diagnosis. So he took a picture of the boy and uploaded the photo to Face2Gene, a diagnostic aid for rare genetic disorders. Sure enough, Mowat-Wilson came up as a potential match. The family agreed to one final genetic test, which was positive for the syndrome.

"If it weren't for the app I'm not sure I would have had the confidence to say 'yes you should spend $1000 on this test,'" says Rahman, who is now the director of Genetic Medicine at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, but saw the boy when he was in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in 2012.

"Families who are dealing with undiagnosed diseases never know what's going to come around the corner, what other organ system might be a problem next week," Rahman says. With a diagnosis, "You don't have to wait for the other shoe to drop because now you know the extent of the condition."

A diagnosis is the first and most important step for patients to attain medical care. Disease prognosis, treatment plans, and emotional coping all stem from this critical phase. But diagnosis can also be the trickiest part of the process, particularly for rare disorders. According to one European survey, 40 percent of rare diseases are initially misdiagnosed.

Healthcare professionals and medical technology companies hope that facial recognition software will help prevent families from facing difficult disruptions due to misdiagnoses.

"Patients with rare diseases or genetic disorders go through a long period of diagnostic odyssey, and just putting a name to a syndrome or finding a diagnosis can be very helpful and relieve a lot of tension for the family," says Dekel Gelbman, CEO of FDNA.

Consequently, a misdiagnosis can be devastating for families. Money and time may have been wasted on fruitless treatments, while opportunities for potentially helpful therapies or clinical trials were missed. Parents led down the wrong path must change their expectations of their child's long-term prognosis and care. In addition, they may be misinformed regarding future decisions about family planning.

Healthcare professionals and medical technology companies hope that facial recognition software will help prevent families from facing these difficult disruptions by improving the accuracy and ease of diagnosing genetic disorders. Traditionally, doctors diagnose these types of conditions by identifying unique patterns of facial features, a practice called dysmorphology. Trained physicians can read a child's face like a map and detect any abnormal ridges or plateaus—wide-set eyes, broad forehead, flat nose, rotated ears—that, combined with other symptoms such as intellectual disability or abnormal height and weight, signify a specific genetic disorder.

These morphological changes can be subtle, though, and often only specialized medical geneticists are able to detect and interpret these facial clues. What's more, some genetic disorders are so rare that even a specialist may not have encountered it before, much less a general practitioner. Diagnosing rare conditions has improved thanks to genomic testing that can confirm (or refute) a doctor's suspicion. Yet with thousands of variants in each person's genome, identifying the culprit mutation or deletion can be extremely difficult if you don't know what you're looking for.

Facial recognition technology is trying to take some of the guesswork out of this process. Software such as the Face2Gene app use machine learning to compare a picture of a patient against images of thousands of disorders and come back with suggestions of possible diagnoses.

"This is a classic field for artificial intelligence because no human being can really have enough knowledge and enough experience to be able to do this for thousands of different disorders."

"When we met a geneticist for the first time we were pretty blown away with the fact that they actually use their own human pattern recognition" to diagnose patients, says Gelbman. "This is a classic field for AI [artificial intelligence], for machine learning because no human being can really have enough knowledge and enough experience to be able to do this for thousands of different disorders."

When a physician uploads a photo to the app, they are given a list of different diagnostic suggestions, each with a heat map to indicate how similar the facial features are to a classic representation of the syndrome. The physician can hone the suggestions by adding in other symptoms or family history. Gelbman emphasized that the app is a "search and reference tool" and should not "be used to diagnose or treat medical conditions." It is not approved by the FDA as a diagnostic.

"As a tool, we've all been waiting for this, something that can help everyone," says Julian Martinez-Agosto, an associate professor in human genetics and pediatrics at UCLA. He sees the greatest benefit of facial recognition technology in its ability to empower non-specialists to make a diagnosis. Many areas, including rural communities or resource-poor countries, do not have access to either medical geneticists trained in these types of diagnostics or genomic screens. Apps like Face2Gene can help guide a general practitioner or flag diseases they might not be familiar with.

One concern is that most textbook images of genetic disorders come from the West, so the "classic" face of a condition is often a child of European descent.

Maximilian Muenke, a senior investigator at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), agrees that in many countries, facial recognition programs could be the only way for a doctor to make a diagnosis.

"There are only geneticists in countries like the U.S., Canada, Europe, Japan. In most countries, geneticists don't exist at all," Muenke says. "In Nigeria, the most populous country in all of Africa with 160 million people, there's not a single clinical geneticist. So in a country like that, facial recognition programs will be sought after and will be extremely useful to help make a diagnosis to the non-geneticists."

One concern about providing this type of technology to a global population is that most textbook images of genetic disorders come from the West, so the "classic" face of a condition is often a child of European descent. However, the defining facial features of some of these disorders manifest differently across ethnicities, leaving clinicians from other geographic regions at a disadvantage.

"Every syndrome is either more easy or more difficult to detect in people from different geographic backgrounds," explains Muenke. For example, "in some countries of Southeast Asia, the eyes are slanted upward, and that happens to be one of the findings that occurs mostly with children with Down Syndrome. So then it might be more difficult for some individuals to recognize Down Syndrome in children from Southeast Asia."

There is a risk that providing this type of diagnostic information online will lead to parents trying to classify their own children.

To combat this issue, Muenke helped develop the Atlas of Human Malformation Syndromes, a database that incorporates descriptions and pictures of patients from every continent. By providing examples of rare genetic disorders in children from outside of the United States and Europe, Muenke hopes to provide clinicians with a better understanding of what to look for in each condition, regardless of where they practice.

There is a risk that providing this type of diagnostic information online will lead to parents trying to classify their own children. Face2Gene is free to download in the app store, although users must be authenticated by the company as a healthcare professional before they can access the database. The NHGRI Atlas can be accessed by anyone through their website. However, Martinez and Muenke say parents already use Google and WebMD to look up their child's symptoms; facial recognition programs and databases are just an extension of that trend. In fact, Martinez says, "Empowering families is another way to facilitate access to care. Some families live in rural areas and have no access to geneticists. If they can use software to get a diagnosis and then contact someone at a large hospital, it can help facilitate the process."

Martinez also says the app could go further by providing greater transparency about how the program makes its assessments. Giving clinicians feedback about why a diagnosis fits certain facial features would offer a valuable teaching opportunity in addition to a diagnostic aid.

Both Martinez and Muenke think the technology is an innovation that could vastly benefit patients. "In the beginning, I was quite skeptical and I could not believe that a machine could replace a human," says Muenke. "However, I am a convert that it actually can help tremendously in making a diagnosis. I think there is a place for facial recognition programs, and I am a firm believer that this will spread over the next five years."

Digital blockchain concept.

The hacker collective known as the Dark Overlord first surfaced in June 2016, when it advertised more than 600,000 patient files from three U.S. healthcare organizations for sale on the dark web. The group, which also attempted to extort ransom from its victims, soon offered another 9 million records pilfered from health insurance companies and provider networks across the country.

Since 2009, federal regulators have counted nearly 5,000 major data breaches in the United States alone, affecting some 260 million individuals.

Last October, apparently seeking publicity as well as cash, the hackers stole a trove of potentially scandalous data from a celebrity plastic surgery clinic in London—including photos of in-progress genitalia- and breast-enhancement surgeries. "We have TBs [terabytes] of this shit. Databases, names, everything," a gang representative told a reporter. "There are some royal families in here."

Bandits like these are prowling healthcare's digital highways in growing numbers. Since 2009, federal regulators have counted nearly 5,000 major data breaches in the United States alone, affecting some 260 million individuals. Although hacker incidents represent less than 20 percent of the total breaches, they account for almost 80 percent of the affected patients. Such attacks expose patients to potential blackmail or identity theft, enable criminals to commit medical fraud or file false tax returns, and may even allow hostile state actors to sabotage electric grids or other infrastructure by e-mailing employees malware disguised as medical notices. According to the consulting agency Accenture, data theft will cost the healthcare industry $305 billion between 2015 and 2019, with annual totals doubling from $40 billion to $80 billion.

Blockchain could put patients in control of their own data, empowering them to access, share, and even sell their medical information as they see fit.

One possible solution to this crisis involves radically retooling the way healthcare data is stored and shared—by using blockchain, the still-emerging information technology that underlies cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin. And blockchain-enabled IT systems, boosters say, could do much more than prevent the theft of medical data. Such networks could revolutionize healthcare delivery on many levels, creating efficiencies that would reduce medical errors, improve coordination between providers, drive down costs, and give researchers unprecedented insights into patterns of disease. Perhaps most transformative, blockchain could put patients in control of their own data, empowering them to access, share, and even sell their medical information as they see fit. Widespread adoption could result in "a new kind of healthcare economy, in which data and services are quantifiable and exchangeable, with strong guarantees around both the security and privacy of sensitive information," wrote W. Brian Smith, chief scientist of healthcare-blockchain startup PokitDok, in a recent white paper.

Around the world, entrepreneurs, corporations, and government agencies are hopping aboard the blockchain train. A survey by the IBM Institute for Business Value, released in late 2016, found that 16 percent of healthcare executives in 16 countries planned to begin implementing some form of the technology in the coming year; 90 percent planned to launch a pilot program in the next two years. In 2017, Estonia became the first country to switch its medical-records system to a blockchain-based framework. Great Britain and Dubai are exploring a similar move. Yet in countries with more fragmented health systems, most notably the U.S., the challenges remain formidable. Some of the most advanced healthcare applications envisioned for blockchain, moreover, raise technological and ethical questions whose answers may not arrive anytime soon.

By creating a detailed, comprehensive, and immutable timeline of medical transactions, blockchain-based recordkeeping could help providers gauge a patient's long-term health patterns in a way that's never before been possible.

What Exactly Is Blockchain, Anyway?

To understand the buzz around blockchain, it's necessary to grasp (at least loosely) how the technology works. Ordinary digital recordkeeping systems rely on a central administrator that acts as gatekeeper to a treasury of data; if you can sneak past the guard, you can often gain access to the entire hoard, and your intrusion may go undetected indefinitely. Blockchain, by contrast, employs a network of synchronized, replicated databases. Information is scattered among these nodes, rather than on a single server, and is exchanged through encrypted, peer-to-peer pathways. Each transaction is visible to every computer on the network, and must be approved by a majority in order to be successfully completed. Each batch of transactions, or "block," is date- and time-stamped, marked with the user's identity, and given a cryptographic code, which is posted to every node. These blocks form a "chain," preserved in an electronic ledger, that can be read by all users but can't be edited. Any unauthorized access, or attempt at tampering, can be quickly neutralized by these overlapping safeguards. Even if a hacker managed to break into the system, penetrating deeply would be extraordinarily difficult.

Because blockchain technology shares transaction records throughout a network, it could eliminate communication bottlenecks between different components of the healthcare system (primary care physicians, specialists, nurses, and so on). And because blockchain-based systems are designed to incorporate programs known as "smart contracts," which automate functions previously requiring human intervention, they could reduce dangerous slipups as well as tedious and costly paperwork. For example, when a patient gets a checkup, sees a specialist, and fills a prescription, all these actions could be automatically recorded on his or her electronic health record (EHR), checked for errors, submitted for billing, and entered on insurance claims—which could be adjudicated and reimbursed automatically as well. "Blockchain has the potential to remove a lot of intermediaries from existing workflows, whether digital or nondigital," says Kamaljit Behera, an industry analyst for the consulting firm Frost & Sullivan.

The possible upsides don't end there. By creating a detailed, comprehensive, and immutable timeline of medical transactions, blockchain-based recordkeeping could help providers gauge a patient's long-term health patterns in a way that's never before been possible. In addition to data entered by their caregivers, individuals could use app-based technologies or wearables to transmit other information to their records, such as diet, exercise, and sleep patterns, adding new depth to their medical portraits.

Many experts expect healthcare blockchain to take root more slowly in the U.S. than in nations with government-run national health services.

Smart contracts could also allow patients to specify who has access to their data. "If you get an MRI and want your orthopedist to see it, you can add him to your network instead of carrying a CD into his office," explains Andrew Lippman, associate director of the MIT Media Lab, who helped create a prototype healthcare blockchain system called MedRec that's currently being tested at Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital in Boston. "Or you might make a smart contract to allow your son or daughter to access your healthcare records if something happens to you." Another option: permitting researchers to analyze your data for scientific purposes, whether anonymously or with your name attached.

The Recent History, and Looking Ahead

Over the past two years, a crowd of startups has begun vying for a piece of the emerging healthcare blockchain market. Some, like PokitDok and Atlanta-based Patientory, plan to mint proprietary cryptocurrencies, which investors can buy in lieu of stock, medical providers may earn as a reward for achieving better outcomes, and patients might score for meeting wellness goals or participating in clinical trials. (Patientory's initial coin offering, or ICO, raised more than $7 million in three days.) Several fledgling healthcare-blockchain companies have found powerful corporate partners: Intel for Silicon Valley's PokitDok, Kaiser Permanente for Patientory, Philips for Los Angeles-based Gem Health. At least one established provider network, Change Healthcare, is developing blockchain-based systems of its own. Two months ago, Change launched what it calls the first "enterprise-scale" blockchain network in U.S. healthcare—a system to track insurance claim submissions and remittances.

No one, however, has set a roll-out date for a full-blown, blockchain-based EHR system in this country. "We have yet to see anything move from the pilot phase to some kind of production status," says Debbie Bucci, an IT architect in the federal government's Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Indeed, many experts expect healthcare blockchain to take root more slowly here than in nations with government-run national health services. In America, a typical patient may have dealings with a family doctor who keeps everything on paper, an assortment of hospitals that use different EHR systems, and an insurer whose system for processing claims is separate from that of the healthcare providers. To help bridge these gaps, a consortium called the Hyperledger Healthcare Working Group (which includes many of the leading players in the field) is developing standard protocols for blockchain interoperability and other functions. Adding to the complexity is the federal Health Insurance and Portability Act (HIPAA), which governs who can access patient data and under what circumstances. "Healthcare blockchain is in a very nascent stage," says Behera. "Coming up with regulations and other guidelines, and achieving large-scale implementation, will take some time."

The ethical implications of buying and selling personal genomic data in an electronic marketplace are doubtless open to debate.

How long? Behera, like other analysts, estimates that relatively simple applications, such as revenue-cycle management systems, could become commonplace in the next five years. More ambitious efforts might reach fruition in a decade or so. But once the infrastructure for healthcare blockchain is fully established, its uses could go far beyond keeping better EHRs.

A handful of scientists and entrepreneurs are already working to develop one visionary application: managing genomic data. Last month, Harvard University geneticist George Church—one of the most influential figures in his discipline—launched a business called Nebula Genomics. It aims to set up an exchange in which individuals can use "Neptune tokens" to purchase DNA sequencing, which will be stored in the company's blockchain-based system; research groups will be able to pay clients for their data using the same cryptocurrency. Luna DNA, founded by a team of biotech veterans in San Diego, plans a similar service, as does a Moscow-based startup called the Zenome Project.

Hossein Rahnama, CEO of the mobile-tech company Flybits and director of research at the Ryerson Centre for Cloud and Context-Aware Computing in Toronto, envisions a more personalized way of sharing genomic data via blockchain. His firm is working with a U.S. insurance company to develop a service that would allow clients in their 20s and 30s to connect with people in their 70s or 80s with similar genomes. The young clients would learn how the elders' lifestyle choices had influenced their health, so that they could modify their own habits accordingly. "It's intergenerational wisdom-sharing," explains Rahnama, who is 38. "I would actually pay to be a part of that network."

The ethical implications of buying and selling personal genomic data in an electronic marketplace are doubtless open to debate. Such commerce could greatly expand the pool of subjects for research in many areas of medicine, enabling the kinds of breakthroughs that only Big Data can provide. Yet it could also lead millions to surrender the most private information of all—the secrets of their cells—to buyers with less benign intentions. The Dark Overlord, one might argue, could not hope for a more satisfying victory.

These scenarios, however, are pure conjecture. After the first web page was posted, in 1991, Lippman observes, "a whole universe developed that you couldn't have imagined on Day 1." The same, he adds, is likely true for healthcare blockchain. "Our vision is to make medical records useful for you and for society, and to give you more control over your own identity. Time will tell."