The Nation’s Science and Health Agencies Face a Credibility Crisis: Can Their Reputations Be Restored?

Morale at federal science agencies -- and public trust in their guidance -- is at a concerning low right now.

This article is part of the magazine, "The Future of Science In America: The Election Issue," co-published by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD.

It didn't have to be this way. More than 200,000 Americans dead, seven million infected, with numbers continuing to climb, an economy in shambles with millions out of work, hundreds of thousands of small businesses crushed with most of the country still under lockdown. And all with no end in sight. This catastrophic result is due in large part to the willful disregard of scientific evidence and of muzzling policy experts by the Trump White House, which has spent its entire time in office attacking science.

One of the few weapons we had to combat the spread of Covid-19—wearing face masks—has been politicized by the President, who transformed this simple public health precaution into a first amendment issue to rally his base. Dedicated public health officials like Dr. Anthony Fauci, the highly respected director of the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases, have received death threats, which have prompted many of them around the country to resign.

Over the summer, the Trump White House pressured the Centers for Disease Control, which is normally in charge of fighting epidemics, to downplay COVID risks among young people and encourage schools to reopen. And in late September, the CDC was forced to pull federal teams who were going door-to-door doing testing surveys in Minnesota because of multiple incidents of threats and abuse. This list goes on and on.

Still, while the Trump administration's COVID failures are the most visible—and deadly—the nation's entire federal science infrastructure has been undermined in ways large and small.

The White House has steadily slashed monies for science—the 2021 budget cuts funding by 10–30% or more for crucial agencies like National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—and has gutted health and science agencies across the board, including key agencies of the Department of Energy and the Interior, especially in divisions that deal with issues they oppose ideologically like climate change.

Even farmers can't get reliable information about how climate change affects planting seasons because the White House moved the entire staff at the U.S. Department of Agriculture agency who does this research, relocating them from Maryland to Kansas City, Missouri. Many of these scientists couldn't uproot their families and sell their homes, so the division has had to pretty much start over from scratch with a skeleton crew.

More than 1,600 federal scientists left government in the first two years of the Trump Administration, according to data compiled by the Washington Post, and one-fifth of top positions in science are vacant, depriving agencies of the expertise they need to fulfill their vital functions. Industry executives and lobbyists have been installed as gatekeepers—HHS Secretary Alex Azar was previously president of Eli Lilly, and three climate change deniers were appointed to key posts at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, to cite just a couple of examples. Trump-appointed officials have sidelined, bullied, or even vilified those who dare to speak out, which chills the rigorous debate that is the essential to sound, independent science.

"The CDC needs to be able to speak regularly to the American people to explain what it knows and how it knows it."

Linda Birnbaum knows firsthand what it's like to become a target. The microbiologist recently retired after more than a decade as the director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, which is the world's largest environmental health organization and the greatest funder of environmental health and toxicology research, a position that often put her agency at odds with the chemical and fossil fuel industry. There was an attempt to get her fired, she says, "because I had the nerve to write that science should be used in making policy. The chemical industry really went after me, and my last two years were not so much fun under this administration. I'd like to believe it was because I was making a difference—if I wasn't, they wouldn't care."

Little wonder that morale at federal agencies is low. "We're very frustrated," says Dr. William Schaffner, a veteran infectious disease specialist and a professor of medicine at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville. "My colleagues within these agencies, the CDC rank and file, are keeping their heads down doing the best they can, and they hope to weather this storm."

The cruel irony is that the United States was once a beacon of scientific innovation. In the heady post World War II years, while Europe lay in ruins, the successful development of penicillin and the atomic bomb—which Americans believed helped vanquish the Axis powers—unleashed a gusher of public money into research, launching an unprecedented era of achievement in American science. Scientists conquered polio, deciphered the genetic code, harnessed the power of the atom, invented lasers, transistors, microchips and computers, sent missions beyond Mars, and landed men on the moon. A once-inconsequential hygiene laboratory was transformed into the colossus the National Institutes of Health has become, which remains today the world's flagship medical research center, unrivaled in size and scope.

At the same time, a tiny public health agency headquartered in Atlanta, which had been in charge of eradicating the malaria outbreaks that plagued impoverished rural areas in the Deep South until the late 1940s, evolved into the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC became the world's leader in fighting disease outbreaks, and the agency's crack team of epidemiologists—members of the vaunted Epidemic Intelligence Service—were routinely dispatched to battle global outbreaks of contagions such as Ebola and malaria and help lead the vaccination campaigns to eradicate killers like polio and small pox that have saved millions of lives.

What will it take to rebuild our federal science infrastructure and restore not only the public's confidence but the respect of the world's scientific community? There are some hopeful signs that there is pushback against the current national leadership, and non-profit watchdog groups like the Union of Concerned Scientists have mapped out comprehensive game plans to restore public trust and the integrity of science.

These include methods of protecting science from political manipulation; restoring the oversight role of independent federal advisory committees, whose numbers were decimated by recent executive orders; strengthening scientific agencies that have been starved by budget cuts and staff attrition; and supporting whistleblower protections and allowing scientists to do their jobs without political meddling to restore integrity to the process. And this isn't just a problem at the CDC. A survey of 1,600 EPA scientists revealed that more than half had been victims of political interference and were pressured to skew their findings, according to research released in April by the Union of Concerned Scientists.

"Federal agencies are staffed by dedicated professionals," says Andrew Rosenberg, director of the Center for Science and Democracy at the Union of Concerned Scientists and a former fisheries biologist for NOAA. "Their job is not to serve the president but the public interest. Inspector generals are continuing to do what they're supposed to, but their findings are not being adhered to. But they need to hold agencies accountable. If an agency has not met its mission or engaged in misconduct, there needs to be real consequences."

On other fronts, last month nine vaccine makers, including Sanofi, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca, took the unprecedented stop of announcing that their COVID-19 vaccines would be thoroughly vetted before they were released. In their implicit refusal to bow to political pressure from the White House to have a vaccine available before the election, their goal was to restore public confidence in vaccine safety, and ensure that enough Americans would consent to have the shot when it was eventually approved so that we'd reach the long-sought holy grail of herd immunity.

"That's why it's really important that all of the decisions need to be made with complete transparency and not taking shortcuts," says Dr. Tom Frieden, president and CEO of Resolve to Save Lives and former director of the CDC during the H1N1, Ebola, and Zika emergencies. "A vaccine is our most important tool, and we can't break that tool by meddling in the science approval process."

In late September, Senate Democrats introduced a new bill to halt political meddling in public health initiatives by the White House. Called Science and Transparency Over Politics Act (STOP), the legislation would create an independent task force to investigate political interference in the federal response to the coronavirus pandemic. "The Trump administration is still pushing the president's political priorities rather than following the science to defeat this virus," Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer said in a press release.

To effectively bring the pandemic under control and restore public confidence, the CDC must assume the leadership role in fighting COVID-19. During previous outbreaks, the top federal infectious disease specialists like Drs. Fauci and Frieden would have daily press briefings, and these need to resume. "The CDC needs to be able to speak regularly to the American people to explain what it knows and how it knows it," says Frieden, who cautions that a vaccine won't be a magic bullet. "There is no one thing that is going to make this virus go away. We need to continue to limit indoor exposures, wear masks, and do strategic testing, isolation, and quarantine. We need a comprehensive approach, and not just a vaccine."

We must also appoint competent and trustworthy leaders, says Rosenberg of the Union of Concerned Scientists. Top posts in too many science agencies are now filled by former industry executives and lobbyists with a built-in bias, as well as people lacking relevant scientific experience, many of whom were never properly vetted because of the current administration's penchant for bypassing Congress and appointing "acting" officials. "We've got great career people who have hung in, but in so much of the federal government, they just put in 'acting' people," says Linda Birnbaum. "They need to bring in better, qualified senior leadership."

Open positions need to be filled, too. Federal science agencies have been seriously crippled by staffing attrition, and the Trump Administration instituted a hiring freeze when it first came in. Staffing levels remain at least ten percent down from previous levels, says Birnbaum and in many agencies, like the EPA, "everything has come to a screeching halt, making it difficult to get anything done."

But in the meantime, the critical first step may be at the ballot box in November. Even Scientific American, the esteemed consumer science publication, for the first time in its 175-year history felt "compelled" to endorse a presidential candidate, Joe Biden, because of the enormity of the damage they say Donald Trump has inflicted on scientists, their legal protections, and on the federal science agencies.

"If the current administration continues, the national political leadership will be emboldened and will be even more assertive of their executive prerogatives and less concerned about traditional niceties, leading to further erosion of the activities of many federal agencies," says Vanderbilt's William Schaffner. "But the reality is, if the team is losing, you change the coach. Then agencies really have to buckle down because it will take some time to restore their hard-earned reputations."

[Editor's Note: To read other articles in this special magazine issue, visit the beautifully designed e-reader version.]

Jamie Rettinger with his now fiance Amie Purnel-Davis, who helped him through the clinical trial.

Jamie Rettinger was still in his thirties when he first noticed a tiny streak of brown running through the thumbnail of his right hand. It slowly grew wider and the skin underneath began to deteriorate before he went to a local dermatologist in 2013. The doctor thought it was a wart and tried scooping it out, treating the affected area for three years before finally removing the nail bed and sending it off to a pathology lab for analysis.

"I have some bad news for you; what we removed was a five-millimeter melanoma, a cancerous tumor that often spreads," Jamie recalls being told on his return visit. "I'd never heard of cancer coming through a thumbnail," he says. None of his doctors had ever mentioned it either. "I just thought I was being treated for a wart." But nothing was healing and it continued to bleed.

A few months later a surgeon amputated the top half of his thumb. Lymph node biopsy tested negative for spread of the cancer and when the bandages finally came off, Jamie thought his medical issues were resolved.

Melanoma is the deadliest form of skin cancer. About 85,000 people are diagnosed with it each year in the U.S. and more than 8,000 die of the cancer when it spreads to other parts of the body, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

There are two peaks in diagnosis of melanoma; one is in younger women ages 30-40 and often is tied to past use of tanning beds; the second is older men 60+ and is related to outdoor activity from farming to sports. Light-skinned people have a twenty-times greater risk of melanoma than do people with dark skin.

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" --Diwakar Davar.

Jamie had a follow up PET scan about six months after his surgery. A suspicious spot on his lung led to a biopsy that came back positive for melanoma. The cancer had spread. Treatment with a monoclonal antibody (nivolumab/Opdivo®) didn't prove effective and he was referred to the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center in Pittsburgh, a four-hour drive from his home in western Ohio.

An alternative monoclonal antibody treatment brought on such bad side effects, diarrhea as often as 15 times a day, that it took more than a week of hospitalization to stabilize his condition. The only options left were experimental approaches in clinical trials.

Early research

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" with a cure rate in the single digits, says Diwakar Davar, 39, an oncologist at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center who specializes in skin cancer. That began to change in 2010 with introduction of the first immunotherapies, monoclonal antibodies, to treat cancer. The antibodies attach to PD-1, a receptor on the surface of T cells of the immune system and on cancer cells. Antibody treatment boosted the melanoma cure rate to about 30 percent. The search was on to understand why some people responded to these drugs and others did not.

At the same time, there was a growing understanding of the role that bacteria in the gut, the gut microbiome, plays in helping to train and maintain the function of the body's various immune cells. Perhaps the bacteria also plays a role in shaping the immune response to cancer therapy.

One clue came from genetically identical mice. Animals ordered from different suppliers sometimes responded differently to the experiments being performed. That difference was traced to different compositions of their gut microbiome; transferring the microbiome from one animal to another in a process known as fecal transplant (FMT) could change their responses to disease or treatment.

When researchers looked at humans, they found that the patients who responded well to immunotherapies had a gut microbiome that looked like healthy normal folks, but patients who didn't respond had missing or reduced strains of bacteria.

Davar and his team knew that FMT had a very successful cure rate in treating the gut dysbiosis of Clostridioides difficile, a persistant intestinal infection, and they wondered if a fecal transplant from a patient who had responded well to cancer immunotherapy treatment might improve the cure rate of patients who did not originally respond to immunotherapies for melanoma.

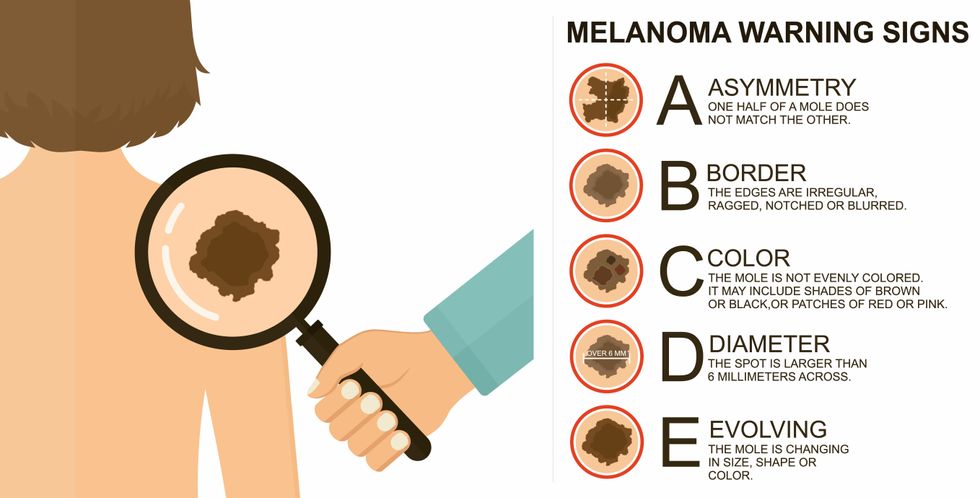

The ABCDE of melanoma detection

Adobe Stock

Clinical trial

"It was pretty weird, I was totally blasted away. Who had thought of this?" Jamie first thought when the hypothesis was explained to him. But Davar's explanation that the procedure might restore some of the beneficial bacterial his gut was lacking, convinced him to try. He quickly signed on in October 2018 to be the first person in the clinical trial.

Fecal donations go through the same safety procedures of screening for and inactivating diseases that are used in processing blood donations to make them safe for transfusion. The procedure itself uses a standard hollow colonoscope designed to screen for colon cancer and remove polyps. The transplant is inserted through the center of the flexible tube.

Most patients are sedated for procedures that use a colonoscope but Jamie doesn't respond to those drugs: "You can't knock me out. I was watching them on the TV going up my own butt. It was kind of unreal at that point," he says. "There were about twelve people in there watching because no one had seen this done before."

A test two weeks after the procedure showed that the FMT had engrafted and the once-missing bacteria were thriving in his gut. More importantly, his body was responding to another monoclonal antibody (pembrolizumab/Keytruda®) and signs of melanoma began to shrink. Every three months he made the four-hour drive from home to Pittsburgh for six rounds of treatment with the antibody drug.

"We were very, very lucky that the first patient had a great response," says Davar. "It allowed us to believe that even though we failed with the next six, we were on the right track. We just needed to tweak the [fecal] cocktail a little better" and enroll patients in the study who had less aggressive tumor growth and were likely to live long enough to complete the extensive rounds of therapy. Six of 15 patients responded positively in the pilot clinical trial that was published in the journal Science.

Davar believes they are beginning to understand the biological mechanisms of why some patients initially do not respond to immunotherapy but later can with a FMT. It is tied to the background level of inflammation produced by the interaction between the microbiome and the immune system. That paper is not yet published.

Surviving cancer

It has been almost a year since the last in his series of cancer treatments and Jamie has no measurable disease. He is cautiously optimistic that his cancer is not simply in remission but is gone for good. "I'm still scared every time I get my scans, because you don't know whether it is going to come back or not. And to realize that it is something that is totally out of my control."

"It was hard for me to regain trust" after being misdiagnosed and mistreated by several doctors he says. But his experience at Hillman helped to restore that trust "because they were interested in me, not just fixing the problem."

He is grateful for the support provided by family and friends over the last eight years. After a pause and a sigh, the ruggedly built 47-year-old says, "If everyone else was dead in my family, I probably wouldn't have been able to do it."

"I never hesitated to ask a question and I never hesitated to get a second opinion." But Jamie acknowledges the experience has made him more aware of the need for regular preventive medical care and a primary care physician. That person might have caught his melanoma at an earlier stage when it was easier to treat.

Davar continues to work on clinical studies to optimize this treatment approach. Perhaps down the road, screening the microbiome will be standard for melanoma and other cancers prior to using immunotherapies, and the FMT will be as simple as swallowing a handful of freeze-dried capsules off the shelf rather than through a colonoscopy. Earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first oral fecal microbiota product for C. difficile, hopefully paving the way for more.

An older version of this hit article was first published on May 18, 2021

All organisms can repair damaged tissue, but none do it better than salamanders and newts. A surprising area of science could tell us how they manage this feat - and perhaps even help us develop a similar ability.

All organisms have the capacity to repair or regenerate tissue damage. None can do it better than salamanders or newts, which can regenerate an entire severed limb.

That feat has amazed and delighted man from the dawn of time and led to endless attempts to understand how it happens – and whether we can control it for our own purposes. An exciting new clue toward that understanding has come from a surprising source: research on the decline of cells, called cellular senescence.

Senescence is the last stage in the life of a cell. Whereas some cells simply break up or wither and die off, others transition into a zombie-like state where they can no longer divide. In this liminal phase, the cell still pumps out many different molecules that can affect its neighbors and cause low grade inflammation. Senescence is associated with many of the declining biological functions that characterize aging, such as inflammation and genomic instability.

Oddly enough, newts are one of the few species that do not accumulate senescent cells as they age, according to research over several years by Maximina Yun. A research group leader at the Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden and the Max Planck Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology and Genetics, in Dresden, Germany, Yun discovered that senescent cells were induced at some stages of regeneration of the salamander limb, “and then, as the regeneration progresses, they disappeared, they were eliminated by the immune system,” she says. “They were present at particular times and then they disappeared.”

Senescent cells added to the edges of the wound helped the healthy muscle cells to “dedifferentiate,” essentially turning back the developmental clock of those cells into more primitive states.

Previous research on senescence in aging had suggested, logically enough, that applying those cells to the stump of a newly severed salamander limb would slow or even stop its regeneration. But Yun stood that idea on its head. She theorized that senescent cells might also play a role in newt limb regeneration, and she tested it by both adding and removing senescent cells from her animals. It turned out she was right, as the newt limbs grew back faster than normal when more senescent cells were included.

Senescent cells added to the edges of the wound helped the healthy muscle cells to “dedifferentiate,” essentially turning back the developmental clock of those cells into more primitive states, which could then be turned into progenitors, a cell type in between stem cells and specialized cells, needed to regrow the muscle tissue of the missing limb. “We think that this ability to dedifferentiate is intrinsically a big part of why salamanders can regenerate all these very complex structures, which other organisms cannot,” she explains.

Yun sees regeneration as a two part problem. First, the cells must be able to sense that their neighbors from the lost limb are not there anymore. Second, they need to be able to produce the intermediary progenitors for regeneration, , to form what is missing. “Molecularly, that must be encoded like a 3D map,” she says, otherwise the new tissue might grow back as a blob, or liver, or fin instead of a limb.

Wound healing

Another recent study, this time at the Mayo Clinic, provides evidence supporting the role of senescent cells in regeneration. Looking closely at molecules that send information between cells in the wound of a mouse, the researchers found that senescent cells appeared near the start of the healing process and then disappeared as healing progressed. In contrast, persistent senescent cells were the hallmark of a chronic wound that did not heal properly. The function and significance of senescence cells depended on both the timing and the context of their environment.

The paper suggests that senescent cells are not all the same. That has become clearer as researchers have been able to identify protein markers on the surface of some senescent cells. The patterns of these proteins differ for some senescent cells compared to others. In biology, such physical differences suggest functional differences, so it is becoming increasingly likely there are subsets of senescent cells with differing functions that have not yet been identified.

There are disagreements within the research community as to whether newts have acquired their regenerative capacity through a unique evolutionary change, or if other animals, including humans, retain this capacity buried somewhere in their genes.

Scientists initially thought that senescent cells couldn’t play a role in regeneration because they could no longer reproduce, says Anthony Atala, a practicing surgeon and bioengineer who leads the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine in North Carolina. But Yun’s study points in the other direction. “What this paper shows clearly is that these cells have the potential to be involved in tissue regeneration [in newts]. The question becomes, will these cells be able to do the same in humans.”

As our knowledge of senescent cells increases, Atala thinks we need to embrace a new analogy to help understand them: humans in retirement. They “have acquired a lot of wisdom throughout their whole life and they can help younger people and mentor them to grow to their full potential. We're seeing the same thing with these cells,” he says. They are no longer putting energy into their own reproduction, but the signaling molecules they secrete “can help other cells around them to regenerate.”

There are disagreements within the research community as to whether newts have acquired their regenerative capacity through a unique evolutionary change, or if other animals, including humans, retain this capacity buried somewhere in their genes. If so, it seems that our genes are unable to express this ability, perhaps as part of a tradeoff in acquiring other traits. It is a fertile area of research.

Dedifferentiation is likely to become an important process in the field of regenerative medicine. One extreme example: a lab has been able to turn back the clock and reprogram adult male skin cells into female eggs, a potential milestone in reproductive health. It will be more difficult to control just how far back one wishes to go in the cell's dedifferentiation – part way or all the way back into a stem cell – and then direct it down a different developmental pathway. Yun is optimistic we can learn these tricks from newts.

Senolytics

A growing field of research is using drugs called senolytics to remove senescent cells and slow or even reverse disease of aging.

“Senolytics are great, but senolytics target different types of senescence,” Yun says. “If senescent cells have positive effects in the context of regeneration, of wound healing, then maybe at the beginning of the regeneration process, you may not want to take them out for a little while.”

“If you look at pretty much all biological systems, too little or too much of something can be bad, you have to be in that central zone” and at the proper time, says Atala. “That's true for proteins, sugars, and the drugs that you take. I think the same thing is true for these cells. Why would they be different?”

Our growing understanding that senescence is not a single thing but a variety of things likely means that effective senolytic drugs will not resemble a single sledge hammer but more a carefully manipulated scalpel where some types of senescent cells are removed while others are added. Combinations and timing could be crucial, meaning the difference between regenerating healthy tissue, a scar, or worse.