The Sickest Babies Are Covered in Wires. New Tech Is Changing That.

A wired baby in a neonatal intensive care unit.

I'll never forget the experience of having a child in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Now more than ever, we're working to remove the barriers between new parents and their infants.

It was another layer of uncertainty that filtered into my experience of being a first-time parent. There was so much I didn't know, and the wires attached to my son's small body for the first week of his life were a reminder of that.

I wanted to be the best mother possible. I deeply desired to bring my son home to start our lives. More than anything, I longed for a wireless baby whom I could hold and love freely without limitations.

The wires suggested my baby was fragile and it left me feeling severely unprepared, anxious, and depressed.

In recent years, research has documented the ways that NICU experiences take a toll on parents' mental health. But thankfully, medical technology is rapidly being developed to help reduce the emotional fallout of the NICU. Now more than ever, we're working to remove the barriers between new parents and their infants. The latest example is the first ever wireless monitoring system that was recently developed by a team at Northwestern University.

After listening to the needs of parents and medical staff, Debra Weese-Mayer, M.D., a professor of pediatric autonomic medicine at Feinberg School of Medicine, along with a team of materials scientists, engineers, dermatologists and pediatricians, set out to develop this potentially life-changing technology. Weese-Mayer believes wireless monitoring will have a significant impact for people on all sides of the NICU experience.

"With elimination of the cumbersome wires," she says, "the parents will find their infant more approachable/less intimidating and have improved access to their long-awaited but delivered-too-early infant, allowing them to begin skin-to-skin contact and holding with reduced concern for dislodging wires."

So how does the new system work?

Very thin "skin like" patches made of silicon rubber are placed on the surface of the skin to monitor vitals like heart rate, respiration rate, and body temperature. One patch is placed on the chest or back and the other is placed on the foot.

These patches are safer on the skin than previously used adhesives, reducing the cuts and infections associated with past methods. Finally, an antenna continuously delivers power, often from under the mattress.

The data collected from the patches stream from the body to a tablet or computer.

New wireless sensor technology is being studied to replace wired monitoring in NICUs in the coming years.

(Northwestern University)

Weese-Mayer hopes that wireless systems will be standard soon, but first they must undergo more thorough testing. "I would hope that in the next five years, wireless monitoring will be the standard in NICUs, but there are many essential validation steps before this technology will be embraced nationally," she says.

Until the new systems are ready, parents will be left struggling with the obstacles that wired monitoring presents.

Physical intimacy, for example, appears to have pain-reducing qualities -- something that is particularly important for babies who are battling serious illness. But wires make those cuddles more challenging.

There's also been minimal discussion about how wired monitoring can be particularly limiting for parents with disabilities and mobility aids, or even C-sections.

"When he was first born and I was recovering from my c-section, I couldn't deal with keeping the wires untangled while trying to sit down without hurting myself," says Rhiannon Giles, a writer from North Carolina, who delivered her son at just over 31 weeks after suffering from severe preeclampsia.

"The wires were awful," she remembers. "They fell off constantly when I shifted positions or he kicked a leg, which meant the monitors would alarm. It felt like an intrusion into the quiet little world I was trying to mentally create for us."

Over the last few years, researchers have begun to dive deeper into the literal and metaphorical challenges of wired monitoring.

For many parents, the wires prompt anxiety that worsens an already tense and vulnerable time.

I'll never forget the first time I got to hold my son without wires. It was the first time that motherhood felt manageable.

"Seeing my five-pound-babies covered in wires from head to toe rendered me completely overwhelmed," recalls Caila Smith, a mom of five from Indiana, whose NICU experience began when her twins were born pre-term. "The nurses seemed to handle them perfectly, but I was scared to touch them while they appeared so medically frail."

During the nine days it took for both twins to come home, the limited access she had to her babies started to impact her mental health. "If we would've had wireless sensors and monitors, it would've given us a much greater sense of freedom and confidence when snuggling our newborns," Smith says.

Besides enabling more natural interactions, wireless monitoring would make basic caregiving tasks much easier, like putting on a onesie.

"One thing I noticed is that many preemie outfits are made with zippers," points out Giles, "which just don't work well when your baby has wires coming off of them, head to toe."

Wired systems can pose issues for medical staff as well as parents.

"The main concern regarding wired systems is that they restrict access to the baby and often get tangled with other equipment, like IV lines," says Lamia Soghier, Medical Director of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Children's National in Washington, D.C , who was also a NICU parent herself. "The nurses have to untangle the wires, which takes time, before handing the baby to the family."

I'll never forget the first time I got to hold my son without wires. It was the first time that motherhood felt manageable, and I couldn't stop myself from crying. Suddenly, anything felt possible and all the limitations from that first week of life seemed to fade away. The rise of wired-free monitoring will make some of the stressors that accompany NICU stays a thing of the past.

The Friday Five: How to exercise for cancer prevention

How to exercise for cancer prevention. Plus, a device that brings relief to back pain, ingredients for reducing Alzheimer's risk, the world's oldest disease could make you young again, and more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- How to exercise for cancer prevention

- A device that brings relief to back pain

- Ingredients for reducing Alzheimer's risk

- Is the world's oldest disease the fountain of youth?

- Scared of crossing bridges? Your phone can help

New approach to brain health is sparking memories

This fall, Robert Reinhart of Boston University published a study finding that electrical stimulation can boost memory - and Reinhart was surprised to discover the effects lasted a full month.

What if a few painless electrical zaps to your brain could help you recall names, perform better on Wordle or even ward off dementia?

This is where neuroscientists are going in efforts to stave off age-related memory loss as well as Alzheimer’s disease. Medications have shown limited effectiveness in reversing or managing loss of brain function so far. But new studies suggest that firing up an aging neural network with electrical or magnetic current might keep brains spry as we age.

Welcome to non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS). No surgery or anesthesia is required. One day, a jolt in the morning with your own battery-operated kit could replace your wake-up coffee.

Scientists believe brain circuits tend to uncouple as we age. Since brain neurons communicate by exchanging electrical impulses with each other, the breakdown of these links and associations could be what causes the “senior moment”—when you can’t remember the name of the movie you just watched.

In 2019, Boston University researchers led by Robert Reinhart, director of the Cognitive and Clinical Neuroscience Laboratory, showed that memory loss in healthy older adults is likely caused by these disconnected brain networks. When Reinhart and his team stimulated two key areas of the brain with mild electrical current, they were able to bring the brains of older adult subjects back into sync — enough so that their ability to remember small differences between two images matched that of much younger subjects for at least 50 minutes after the testing stopped.

Reinhart wowed the neuroscience community once again this fall. His newer study in Nature Neuroscience presented 150 healthy participants, ages 65 to 88, who were able to recall more words on a given list after 20 minutes of low-intensity electrical stimulation sessions over four consecutive days. This amounted to a 50 to 65 percent boost in their recall.

Even Reinhart was surprised to discover the enhanced performance of his subjects lasted a full month when they were tested again later. Those who benefited most were the participants who were the most forgetful at the start.

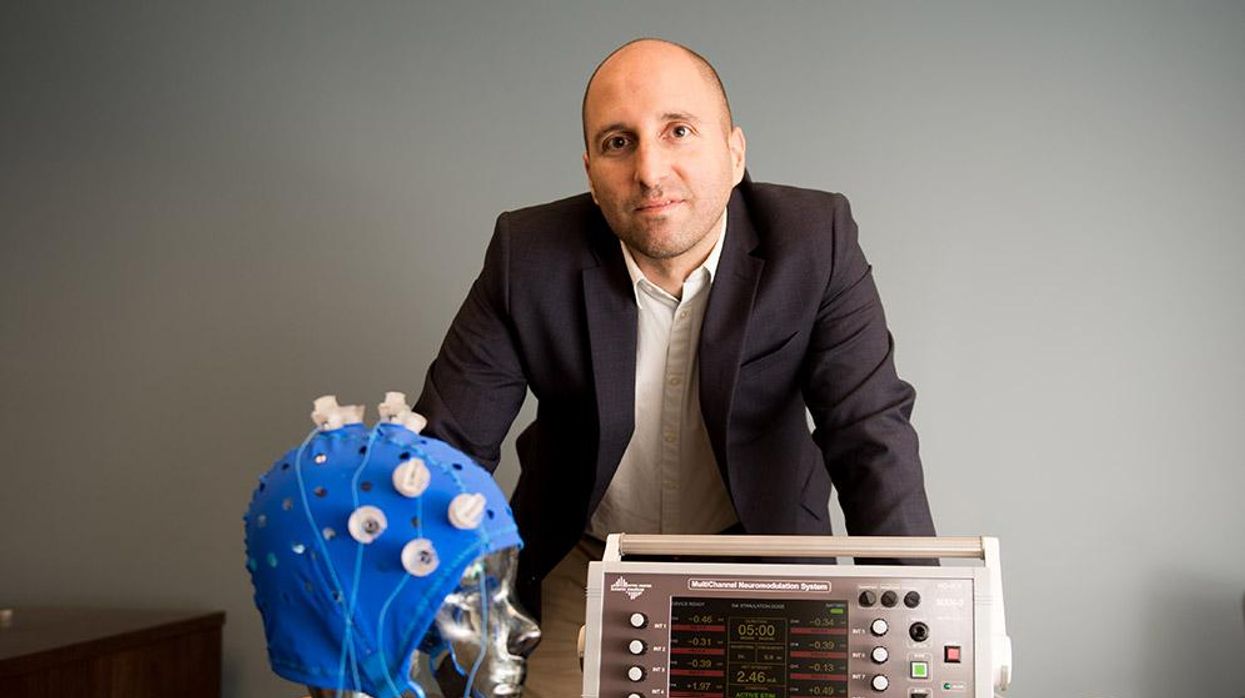

An older person participates in Robert Reinhart's research on brain stimulation.

Robert Reinhart

Reinhart’s subjects only suffered normal age-related memory deficits, but NIBS has great potential to help people with cognitive impairment and dementia, too, says Krista Lanctôt, the Bernick Chair of Geriatric Psychopharmacology at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center in Toronto. Plus, “it is remarkably safe,” she says.

Lanctôt was the senior author on a meta-analysis of brain stimulation studies published last year on people with mild cognitive impairment or later stages of Alzheimer’s disease. The review concluded that magnetic stimulation to the brain significantly improved the research participants’ neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as apathy and depression. The stimulation also enhanced global cognition, which includes memory, attention, executive function and more.

This is the frontier of neuroscience.

The two main forms of NIBS – and many questions surrounding them

There are two types of NIBS. They differ based on whether electrical or magnetic stimulation is used to create the electric field, the type of device that delivers the electrical current and the strength of the current.

Transcranial Current Brain Stimulation (tES) is an umbrella term for a group of techniques using low-wattage electrical currents to manipulate activity in the brain. The current is delivered to the scalp or forehead via electrodes attached to a nylon elastic cap or rubber headband.

Variations include how the current is delivered—in an alternating pattern or in a constant, direct mode, for instance. Tweaking frequency, potency or target brain area can produce different effects as well. Reinhart’s 2022 study demonstrated that low or high frequencies and alternating currents were uniquely tied to either short-term or long-term memory improvements.

Sessions may be 20 minutes per day over the course of several days or two weeks. “[The subject] may feel a tingling, warming, poking or itching sensation,” says Reinhart, which typically goes away within a minute.

The other main approach to NIBS is Transcranial Magnetic Simulation (TMS). It involves the use of an electromagnetic coil that is held or placed against the forehead or scalp to activate nerve cells in the brain through short pulses. The stimulation is stronger than tES but similar to a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

The subject may feel a slight knocking or tapping on the head during a 20-to-60-minute session. Scalp discomfort and headaches are reported by some; in very rare cases, a seizure can occur.

No head-to-head trials have been conducted yet to evaluate the differences and effectiveness between electrical and magnetic current stimulation, notes Lanctôt, who is also a professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto. Although TMS was approved by the FDA in 2008 to treat major depression, both techniques are considered experimental for the purpose of cognitive enhancement.

“One attractive feature of tES is that it’s inexpensive—one-fifth the price of magnetic stimulation,” Reinhart notes.

Don’t confuse either of these procedures with the horrors of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in the 1950s and ‘60s. ECT is a more powerful, riskier procedure used only as a last resort in treating severe mental illness today.

Clinical studies on NIBS remain scarce. Standardized parameters and measures for testing have not been developed. The high heterogeneity among the many existing small NIBS studies makes it difficult to draw general conclusions. Few of the studies have been replicated and inconsistencies abound.

Scientists are still lacking so much fundamental knowledge about the brain and how it works, says Reinhart. “We don’t know how information is represented in the brain or how it’s carried forward in time. It’s more complex than physics.”

Lanctôt’s meta-analysis showed improvements in global cognition from delivering the magnetic form of the stimulation to people with Alzheimer’s, and this finding was replicated inan analysis in the Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease this fall. Neither meta-analysis found clear evidence that applying the electrical currents, was helpful for Alzheimer’s subjects, but Lanctôt suggests this might be merely because the sample size for tES was smaller compared to the groups that received TMS.

At the same time, London neuroscientist Marco Sandrini, senior lecturer in psychology at the University of Roehampton, critically reviewed a series of studies on the effects of tES on episodic memory. Often declining with age, episodic memory relates to recalling a person’s own experiences from the past. Sandrini’s review concluded that delivering tES to the prefrontal or temporoparietal cortices of the brain might enhance episodic memory in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and amnesiac mild cognitive impairment (the predementia phase of Alzheimer’s when people start to have symptoms).

Researchers readily tick off studies needed to explore, clarify and validate existing NIBS data. What is the optimal stimulus session frequency, spacing and duration? How intense should the stimulus be and where should it be targeted for what effect? How might genetics or degree of brain impairment affect responsiveness? Would adjunct medication or cognitive training boost positive results? Could administering the stimulus while someone sleeps expedite memory consolidation?

Using MRI or another brain scan along with computational modeling of the current flow, a clinician could create a treatment that is customized to each person’s brain.

While Sandrini’s review reported improvements induced by tES in the recall or recognition of words and images, there is no evidence it will translate into improvements in daily activities. This is another question that will require more research and testing, Sandrini notes.

Scientists are still lacking so much fundamental knowledge about the brain and how it works, says Reinhart. “We don’t know how information is represented in the brain or how it’s carried forward in time. It’s more complex than physics.”

Where the science is headed

Learning how to apply precision medicine to NIBS is the next focus in advancing this technology, says Shankar Tumati, a post-doctoral fellow working with Lanctôt.

There is great variability in each person’s brain anatomy—the thickness of the skull, the brain’s unique folds, the amount of cerebrospinal fluid. All of these structural differences impact how electrical or magnetic stimulation is distributed in the brain and ultimately the effects.

Using MRI or another brain scan along with computational modeling of the current flow, a clinician could create a treatment that is customized to each person’s brain, from where to put the electrodes to determining the exact dose and duration of stimulation needed to achieve lasting results, Sandrini says.

Above all, most neuroscientists say that largescale research studies over long periods of time are necessary to confirm the safety and durability of this therapy for the purpose of boosting memory. Short of that, there can be no FDA approval or medical regulation for this clinical use.

Lanctôt urges people to seek out clinical NIBS trials in their area if they want to see the science advance. “That is how we’ll find the answers,” she says, predicting it will be 5 to 10 years to develop each additional clinical application of NIBS. Ultimately, she predicts that reigning in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment will require a multi-pronged approach that includes lifestyle and medications, too.

Sandrini believes that scientific efforts should focus on preventing or delaying Alzheimer’s. “We need to start intervention earlier—as soon as people start to complain about forgetting things,” he says. “Changes in the brain start 10 years before [there is a problem]. Once Alzheimer’s develops, it is too late.”