The Sickest Babies Are Covered in Wires. New Tech Is Changing That.

A wired baby in a neonatal intensive care unit.

I'll never forget the experience of having a child in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Now more than ever, we're working to remove the barriers between new parents and their infants.

It was another layer of uncertainty that filtered into my experience of being a first-time parent. There was so much I didn't know, and the wires attached to my son's small body for the first week of his life were a reminder of that.

I wanted to be the best mother possible. I deeply desired to bring my son home to start our lives. More than anything, I longed for a wireless baby whom I could hold and love freely without limitations.

The wires suggested my baby was fragile and it left me feeling severely unprepared, anxious, and depressed.

In recent years, research has documented the ways that NICU experiences take a toll on parents' mental health. But thankfully, medical technology is rapidly being developed to help reduce the emotional fallout of the NICU. Now more than ever, we're working to remove the barriers between new parents and their infants. The latest example is the first ever wireless monitoring system that was recently developed by a team at Northwestern University.

After listening to the needs of parents and medical staff, Debra Weese-Mayer, M.D., a professor of pediatric autonomic medicine at Feinberg School of Medicine, along with a team of materials scientists, engineers, dermatologists and pediatricians, set out to develop this potentially life-changing technology. Weese-Mayer believes wireless monitoring will have a significant impact for people on all sides of the NICU experience.

"With elimination of the cumbersome wires," she says, "the parents will find their infant more approachable/less intimidating and have improved access to their long-awaited but delivered-too-early infant, allowing them to begin skin-to-skin contact and holding with reduced concern for dislodging wires."

So how does the new system work?

Very thin "skin like" patches made of silicon rubber are placed on the surface of the skin to monitor vitals like heart rate, respiration rate, and body temperature. One patch is placed on the chest or back and the other is placed on the foot.

These patches are safer on the skin than previously used adhesives, reducing the cuts and infections associated with past methods. Finally, an antenna continuously delivers power, often from under the mattress.

The data collected from the patches stream from the body to a tablet or computer.

New wireless sensor technology is being studied to replace wired monitoring in NICUs in the coming years.

(Northwestern University)

Weese-Mayer hopes that wireless systems will be standard soon, but first they must undergo more thorough testing. "I would hope that in the next five years, wireless monitoring will be the standard in NICUs, but there are many essential validation steps before this technology will be embraced nationally," she says.

Until the new systems are ready, parents will be left struggling with the obstacles that wired monitoring presents.

Physical intimacy, for example, appears to have pain-reducing qualities -- something that is particularly important for babies who are battling serious illness. But wires make those cuddles more challenging.

There's also been minimal discussion about how wired monitoring can be particularly limiting for parents with disabilities and mobility aids, or even C-sections.

"When he was first born and I was recovering from my c-section, I couldn't deal with keeping the wires untangled while trying to sit down without hurting myself," says Rhiannon Giles, a writer from North Carolina, who delivered her son at just over 31 weeks after suffering from severe preeclampsia.

"The wires were awful," she remembers. "They fell off constantly when I shifted positions or he kicked a leg, which meant the monitors would alarm. It felt like an intrusion into the quiet little world I was trying to mentally create for us."

Over the last few years, researchers have begun to dive deeper into the literal and metaphorical challenges of wired monitoring.

For many parents, the wires prompt anxiety that worsens an already tense and vulnerable time.

I'll never forget the first time I got to hold my son without wires. It was the first time that motherhood felt manageable.

"Seeing my five-pound-babies covered in wires from head to toe rendered me completely overwhelmed," recalls Caila Smith, a mom of five from Indiana, whose NICU experience began when her twins were born pre-term. "The nurses seemed to handle them perfectly, but I was scared to touch them while they appeared so medically frail."

During the nine days it took for both twins to come home, the limited access she had to her babies started to impact her mental health. "If we would've had wireless sensors and monitors, it would've given us a much greater sense of freedom and confidence when snuggling our newborns," Smith says.

Besides enabling more natural interactions, wireless monitoring would make basic caregiving tasks much easier, like putting on a onesie.

"One thing I noticed is that many preemie outfits are made with zippers," points out Giles, "which just don't work well when your baby has wires coming off of them, head to toe."

Wired systems can pose issues for medical staff as well as parents.

"The main concern regarding wired systems is that they restrict access to the baby and often get tangled with other equipment, like IV lines," says Lamia Soghier, Medical Director of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Children's National in Washington, D.C , who was also a NICU parent herself. "The nurses have to untangle the wires, which takes time, before handing the baby to the family."

I'll never forget the first time I got to hold my son without wires. It was the first time that motherhood felt manageable, and I couldn't stop myself from crying. Suddenly, anything felt possible and all the limitations from that first week of life seemed to fade away. The rise of wired-free monitoring will make some of the stressors that accompany NICU stays a thing of the past.

Scientists Just Started Testing a New Class of Drugs to Slow--and Even Reverse--Aging

Eliminating "zombie-like" cells, called senescent cells, may hold the key to slowing aging and its chronic diseases.

Imagine reversing the processes of aging. It's an age-old quest, and now a study from the Mayo Clinic may be the first ray of light in the dawn of that new era.

The immune system can handle a certain amount of senescence, but that capacity declines with age.

The small preliminary report, just nine patients, primarily looked at the safety and tolerability of the compounds used. But it also showed that a new class of small molecules called senolytics, which has proven to reverse markers of aging in animal studies, can work in humans.

Aging is a relentless assault of chronic diseases including Alzheimer's, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and frailty. Developing one chronic condition strongly predicts the rapid onset of another. They pile on top of each other and impede the body's ability to respond to the next challenge.

"Potentially, by targeting fundamental aging processes, it may be possible to delay or prevent or alleviate multiple age-related conditions and many diseases as a group, instead of one at a time," says James Kirkland, the Mayo Clinic physician who led the study and is a top researcher in the growing field of geroscience, the biology of aging.

Getting Rid of "Zombie" Cells

One element common to many of the diseases is senescence, a kind of limbo or zombie-like state where cells no longer divide or perform many regular functions, but they don't die. Senescence is thought to be beneficial in that it inhibits the cancerous proliferation of cells. But in aging, the senescent cells still produce molecules that create inflammation both locally and throughout the body. It is a cycle that feeds upon itself, slowly ratcheting down normal body function and health.

Disease and harmful stimuli like radiation to treat cancer can also generate senescence, which is why young cancer patients seem to experience earlier and more rapid aging. The immune system can handle a certain amount of senescence, but that capacity declines with age. There also appears to be a threshold effect, a tipping point where senescence becomes a dominant factor in aging.

Kirkland's team used an artificial intelligence approach called machine learning to look for cell signaling networks that keep senescent cells from dying. To date, researchers have identified at least eight such signaling networks, some of which seem to be unique to a particular type of cell or tissue, but others are shared or overlap.

Then a computer search identified molecules known to disrupt these signaling pathways "and allow cells that are fully senescent to kill themselves," he explains. The process is a bit like looking for the right weapons in a video game to wipe out lingering zombie cells. But instead of swords, guns, and grenades, the list of biological tools so far includes experimental molecules, approved drugs, and natural supplements.

Treatment

"We found early on that targeting single components of those networks will only kill a very small minority of senescent cells or senescent cell types," says Kirkland. "So instead of going after one drug-one target-one disease, we're going after networks with combinations of drugs or drugs that have multiple targets. And we're going after every age-related disease."

The FDA is grappling with guidance for researchers wanting to conduct clinical trials on something as broad as aging rather than a single disease.

The large number of potential senolytic (i.e. zombie-neutralizing) compounds they identified allowed Kirkland to be choosy, "purposefully selecting drugs where the side effects profile was good...and with short elimination half-lives." The hit and run approach meant they didn't have to worry about maintaining a steady state of drugs in the body for an extended period of time. Some of the compounds they selected need only a half hour exposure to trigger the dying process in senescent cells, which can then take several days.

Work in mice has already shown impressive results in reversing diabetes, weight gain, Alzheimer's, cardiovascular disease and other conditions using senolytic agents.

That led to Kirkland's pilot study in humans with diabetes-related kidney disease using a three-day regimen of dasatinib, a kinase inhibitor first approved in 2006 to treat some forms of blood cancer, and quercetin, a flavonoid found in many plants and sold as a food supplement.

The combination was safe and well tolerated; it reduced the number of senescent cells in the belly fat of patients and restored their normal function, according to results published in September in the journal EBioMedicine. This preliminary paper was based on 9 patients in an ongoing study of 30 patients.

Kirkland cautions that these are initial and incomplete findings looking primarily at safety issues, not effectiveness. There is still much to be learned about the use of senolytics, starting with proof that they actually provide clinical benefit, and against what chronic conditions. The drug combinations, doses, duration, and frequency, not to mention potential risks all must be worked out. Additional studies of other diseases are being developed.

What's Next

Ron Kohanski, a senior administrator at the NIH National Institute on Aging (NIA), says the field of senolytics is so new that there isn't even a consensus on how to identify a senescent cell, and the FDA is grappling with guidance for researchers wanting to conduct clinical trials on something as broad as aging rather than a single disease.

Intellectual property concerns may temper the pharmaceutical industry's interest in developing senolytics to treat chronic diseases of aging. It looks like many mix-and-match combinations are possible, and many of the potential molecules identified so far are found in nature or are drugs whose patents have or will soon expire. So the ability to set high prices for such future drugs, and hence the willingness to spend money on expensive clinical trials, may be limited.

Still, Kohanski believes the field can move forward quickly because it often will include products that are already widely used and have a known safety profile. And approaches like Kirkland's hit and run strategy will minimize potential exposure and risk.

He says the NIA is going to support a number of clinical trials using these new approaches. Pharmaceutical companies may feel that they can develop a unique part of a senolytic combination regimen that will justify their investment. And if they don't, countries with socialized medicine may take the lead in supporting such research with the goal of reducing the costs of treating aging patients.

A New Test Aims to Objectively Measure Pain. It Could Help Legitimate Sufferers Access the Meds They Need.

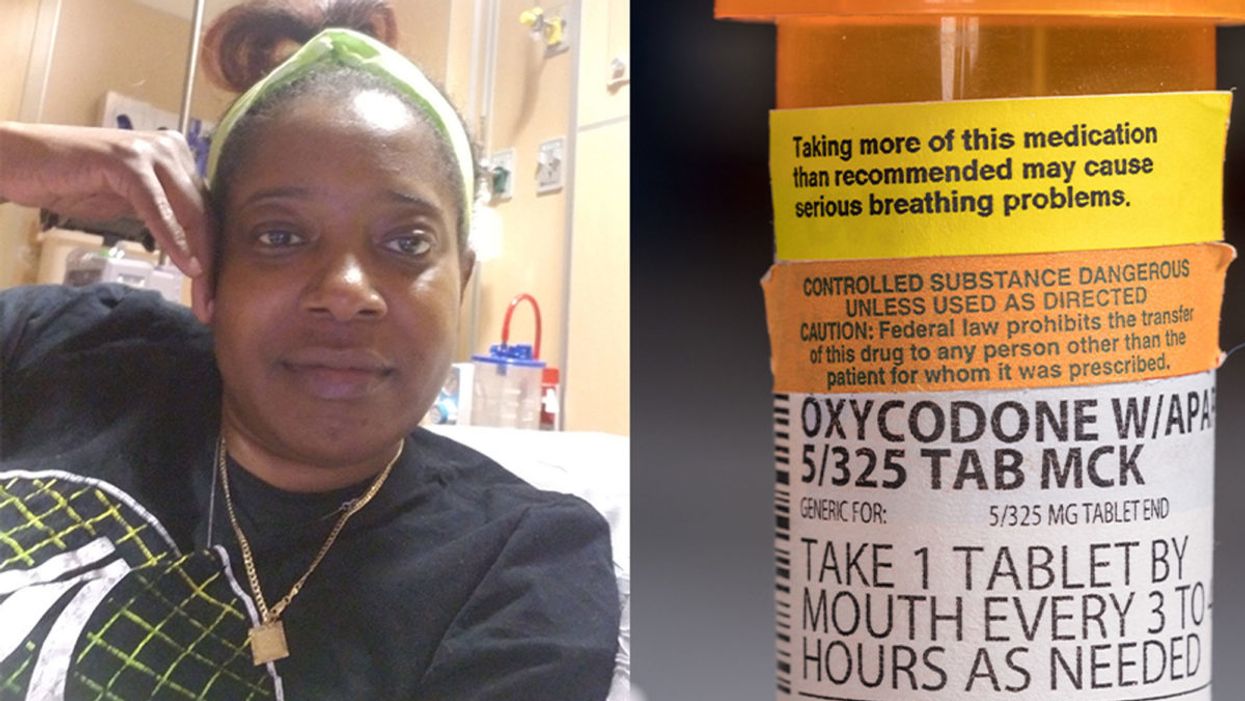

Sickle cell patient Bridgett Willkie found herself being labeled an addict when she sought an opioid prescription to control her pain.

"That throbbing you feel for the first minute after a door slams on your finger."

This is how Central Florida resident Bridgett Willkie describes the attacks of pain caused by her sickle cell anemia – a genetic blood disorder in which a patient's red blood cells become shaped like sickles and get stuck in blood vessels, thereby obstructing the flow of blood and oxygen.

"I found myself being labeled as an addict and I never was."

Willkie's lifelong battle with the condition has led to avascular necrosis in both of her shoulders, hips, knees and ankles. This means that her bone tissue is dying due to insufficient blood supply (sickle cell anemia is among the medical conditions that can decrease blood flow to one's bones).

"That adds to the pain significantly," she says. "Every time my heart beats, it hurts. And the pain moves. It follows the path of circulation. I liken it to a traffic jam in my veins."

For more than a decade, she received prescriptions for Oxycontin. Then, four years ago, her hematologist – who had been her doctor for 18 years – suffered a fatal heart attack. She says her longtime doctor's replacement lacked experience treating sickle cell patients and was uncomfortable writing her a prescription for opioids. What's more, this new doctor wanted to place her in a drug rehab facility.

"Because I refused to go, he stopped writing my scripts," she says. The ensuing three months were spent at home, detoxing. She describes the pain as unbearable. "Sometimes I just wanted to die."

One of the effects of the opioid epidemic is that many legitimate pain patients have seen their opioids significantly reduced or downright discontinued because of their doctors' fears of over-prescribing addictive medications.

"I found myself being labeled as an addict and I never was...Being treated like a drug-seeking patient is degrading and humiliating," says Willkie, who adds that when she is at the hospital, "it's exhausting arguing with the doctors...You dread them making their rounds because every day they come in talking about weaning you off your meds."

Situations such as these are fraught with tension between patients and doctors, who must remain wary about the risk of over-prescribing powerful and addictive medications. Adding to the complexity is that it can be very difficult to reliably assess a patient's level of physical pain.

However, this difficulty may soon decline, as Indiana University School of Medicine researchers, led by Dr. Alexander B. Niculescu, have reportedly devised a way to objectively assess physical pain by analyzing biomarkers in a patient's blood sample. The results of a study involving more than 300 participants were published earlier this year in the journal Molecular Psychiatry.

Niculescu – who is both a professor of psychiatry and medical neuroscience at the IU School of Medicine – explains that, when someone is in severe physical pain, a blood sample will show biomarkers related to intracellular adhesion and cell-signaling mechanisms. He adds that some of these biomarkers "have prior convergent evidence from animal or human studies for involvement in pain."

Aside from reliably measuring pain severity, Niculescu says blood biomarkers can measure the degree of one's response to treatment and also assess the risk of future recurrences of pain. He believes this new method's greatest benefit, however, might be the ability to identify a number of non-opioid medications that a particular patient is likely to respond to, based on his or her biomarker profile.

Clearly, such a method could be a gamechanger for pain patients and the professionals who treat them. As of yet, health workers have been forced to make crucial decisions based on their clinical impressions of patients; such impressions are invariably subjective. A method that enables people to prove the extent of their pain could remove the stigma that many legitimate pain patients face when seeking to obtain their needed medicine. It would also improve their chances of receiving sufficient treatment.

Niculescu says it's "theoretically possible" that there are some conditions which, despite being severe, might not reveal themselves through his testing method. But he also says that, "even if the same molecular markers that are involved in the pain process are not reflected in the blood, there are other indirect markers that should reflect the distress."

Niculescu expects his testing method will be available to the medical community at large within one to three years.

Willkie says she would welcome a reliable pain assessment method. Well-aware that she is not alone in her plight, she has more than 500 Facebook friends with sickle cell disease, and she says that "all of their opioid meds have been restricted or cut" as a result of the opioid crisis. Some now feel compelled to find their opioids "on the streets." She says she personally has never obtained opioids this way. Instead, she relies on marijuana to mitigate her pain.

Niculescu expects his testing method will be available to the medical community at large within one to three years: "It takes a while for things to translate from a lab setting to a commercial testing arena."

In the meantime, for Willkie and other patients, "we have to convince doctors and nurses that we're in pain."