These Sisters May Change the Way You Think About Dying

Anita Freeman, left, hugs her sister Elizabeth Martin at a bakery in Huntington Beach, California, in 2009 — a year before Elizabeth's cancer diagnosis. (Courtesy Anita Freeman)

For five weeks, Anita Freeman watched her sister writhe in pain. The colon cancer diagnosed four years earlier became metastatic.

"I still wouldn't wish that ending on my worst enemy."

At this tormenting juncture, her 66-year-old sister, Elizabeth Martin, wanted to die comfortably in her sleep. But doctors wouldn't help fulfill that final wish.

"It haunts me," Freeman, 74, who lives in Long Beach, California, says in recalling the prolonged agony. Her sister "was breaking out of the house and running in her pajamas down the sidewalk, screaming, 'Help me. Help me.' She just went into a total panic."

Finally, a post-acute care center offered pentobarbital, a sedative that induced a state of unconsciousness, but only after an empathetic palliative care doctor called and insisted on ending the inhumane suffering. "We even had to fight the owners of the facility to get them to agree to the recommendations," Freeman says, describing it as "the only option we had at that time; I still wouldn't wish that ending on my worst enemy."

Her sister died a week later, in 2014. That was two years before California's medical aid-in-dying law took effect, making doctors less reliant on palliative sedation to peacefully end unbearable suffering for terminally ill patients. Now, Freeman volunteers for Compassion & Choices, a national grassroots organization based in Portland, Oregon, that advocates for expanding end-of-life options.

Palliative sedation involves medicating a terminally ill patient into lowered awareness or unconsciousness in order to relieve otherwise intractable suffering at the end of life. It is not intended to cause death, which occurs due to the patient's underlying disease.

In contrast, euthanasia involves directly and deliberately ending a patient's life. Euthanasia is legal only in Canada and some European countries and requires a health care professional to administer the medication. In the United States, laws in seven states and Washington, D.C. give terminally ill patients the option to obtain prescription medication they can take to die peacefully in their sleep, but they must be able to self-adminster it.

Recently, palliative sedation has been gaining more acceptance among medical professionals as an occasional means to relieve suffering, even if it may advance the time of death, as some clinicians believe. However, studies have found no evidence of this claim. Many doctors and bioethicists emphasize that intent is what distinguishes palliative sedation from euthanasia. Others disagree. It's common for controversy to swirl around when and how to apply this practice.

Elizabeth Martin with her sister Anita Freeman in happier times, before metastatic cancer caused her tremendous suffering at the end of her life.

(Courtesy Anita Freeman)

"Intent is everything in ethics. The rigor and protocols we have around palliative sedation therapy also speaks to it being an intervention directed to ease refractory distress," says Martha Twaddle, medical director of palliative medicine and supportive care at Northwestern University's Lake Forest Hospital in Lake Forest, Illinois.

Palliative sedation should be considered only when pain, shortness of breath, and other unbearable symptoms don't respond to conventional treatments. Left to his or her own devices, a patient in this predicament could become restless, Twaddle says, noting that "agitated delirium is a horrible symptom for a family to witness."

At other times, "we don't want to be too quick to sedate," particularly in cases of purely "existential distress"—when a patient experiences anticipatory grief around "saying goodbye" to loved ones, she explains. "We want to be sure we're applying the right therapy for the problem."

Encouraging patients to reconcile with their kin may help them find inner peace. Nonmedical interventions worth exploring include quieting the environment and adjusting lighting to simulate day and night, Twaddle says.

Music-thanatology also can have a calming effect. It is live, prescriptive music, mainly employing the harp or voice, tailored to the patient's physiological needs by tuning into vital signs such as heart rate, respiration, and temperature, according to the Music-Thanatology Association International.

"When we integrated this therapeutic modality in 2003, our need for using palliative sedation therapy dropped 75 percent and has remained low ever since," Twaddle observes. "We have this as part of our care for treating refractory symptoms."

"If palliative sedation is being employed properly with the right patient, it should not hasten death."

Ethical concerns surrounding euthanasia often revolve around the term "terminal sedation," which "can entail a physician deciding that the patient is a lost cause—incurable medically and in substantial pain that cannot adequately be relieved," says John Kilner, professor and director of the bioethics programs at Trinity International University in Deerfield, Illinois.

By halting sedation at reasonable intervals, the care team can determine whether significant untreatable pain persists. Periodic discontinuation serves as "evidence that the physician is still working to restore the patient rather than merely to usher the patient painlessly into death," Kilner explains. "Indeed, sometimes after a period of unconsciousness, with the body relieved of unceasing pain, the body can recover enough to make the pain treatable."

The medications for palliative sedation "are tried and true sedatives that we've had for a long time, for many years, so they're predictable," says Joe Rotella, chief medical officer at the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.

Some patients prefer to keep their eyes open and remain conscious to answer by name, while others tell their doctors in advance that they want to be more heavily sedated while receiving medications to manage pain and other symptoms. "We adjust the dosage until the patient is sleeping at a desired level of sedation," Rotella says.

Sedation is an intrinsic side effect of most medications prescribed to control severe symptoms in terminally ill patients. In general, most people die in a sleepy state, except for instances of sudden, dramatic death resulting from a major heart attack or stroke, says Ryan R. Nash, a palliative medicine physician and director of The Ohio State University Center for Bioethics in Columbus.

"Using those medications to treat pain or shortness of breath is not palliative sedation," Nash says. In addition, providing supplemental nutrition and hydration in situations where death is imminent—with a prognosis limited to hours or days—generally doesn't help prolong life. "If palliative sedation is being employed properly with the right patient," he adds, "it should not hasten death."

Nonetheless, hospice nurses sometimes feel morally distressed over carrying out palliative sedation. Implementing protocols at health systems would help guide them and alleviate some of their concerns, says Gregg VandeKieft, medical director for palliative care at Providence St. Joseph Health's Southwest Washington Region in Olympia, Washington. "It creates guardrails by sort of standardizing and normalizing things," he says.

"Our goal is to restore our patient. It's never to take their life."

The concept of proportionality weighs heavily in the process of palliative sedation. But sometimes substantial doses are necessary. For instance, an opioid-tolerant patient recently needed an unusually large amount of medication to control symptoms. She was in a state of illness-induced confusion and pain, says David E. Smith, a palliative medicine physician at Baptist Health Supportive Care in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Still, "we are parsimonious in what we do. We only use as much therapeutic force as necessary to achieve our goals," Smith says. "Our goal is to restore our patient. It's never to take their life."

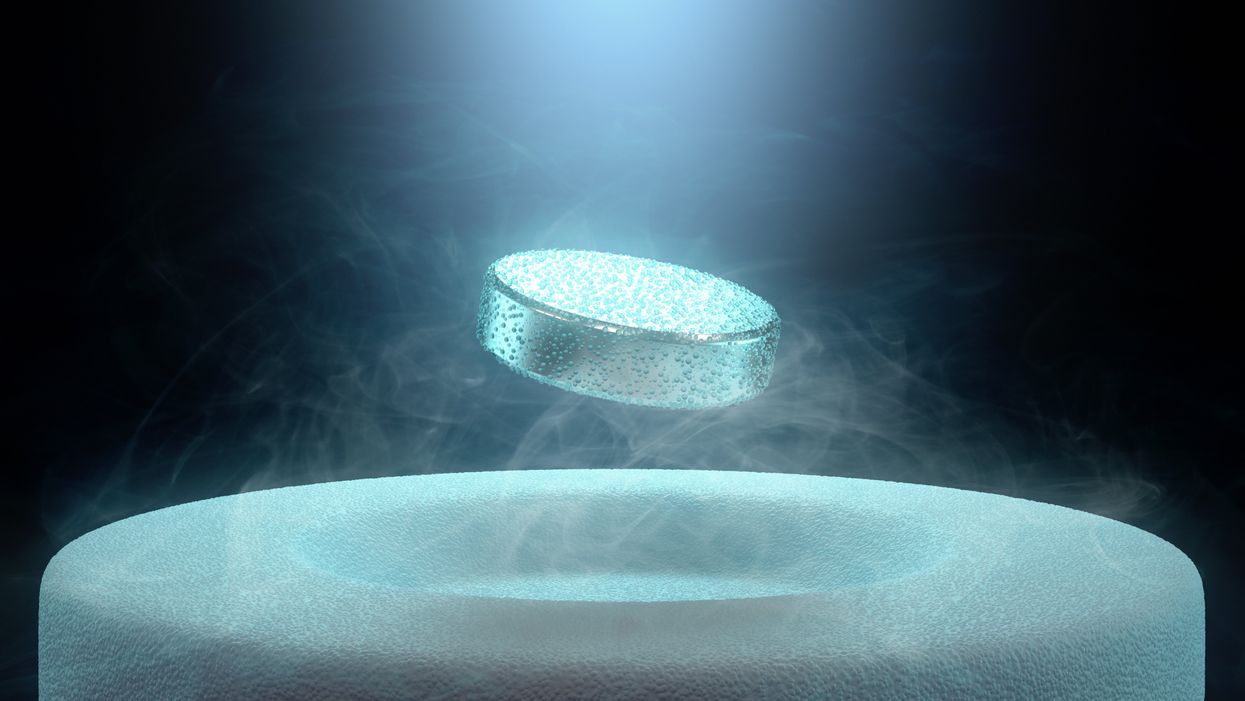

Researchers claimed they built a breakthrough superconductor. Social media shot it down almost instantly.

In July, South Korean scientists posted a paper finding they had achieved superconductivity - a claim that was debunked within days.

Harsh Mathur was a graduate physics student at Yale University in late 1989 when faculty announced they had failed to replicate claims made by scientists at the University of Utah and the University of Wolverhampton in England.

Such work is routine. Replicating or attempting to replicate the contraptions, calculations and conclusions crafted by colleagues is foundational to the scientific method. But in this instance, Yale’s findings were reported globally.

“I had a ringside view, and it was crazy,” recalls Mathur, now a professor of physics at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio.

Yale’s findings drew so much attention because initial experiments by Stanley Pons of Utah and Martin Fleischmann of Wolverhampton led to a startling claim: They were able to fuse atoms at room temperature – a scientific El Dorado known as “cold fusion.”

Nuclear fusion powers the stars in the universe. However, star cores must be at least 23.4 million degrees Fahrenheit and under extraordinary pressure to achieve fusion. Pons and Fleischmann claimed they had created an almost limitless source of power achievable at any temperature.

Like fusion, superconductivity can only be achieved in mostly impractical circumstances.

But about six months after they made their startling announcement, the pair’s findings were discredited by researchers at Yale and the California Institute of Technology. It was one of the first instances of a major scientific debunking covered by mass media.

Some scholars say the media attention for cold fusion stemmed partly from a dazzling announcement made three years prior in 1986: Scientists had created the first “superconductor” – material that could transmit electrical current with little or no resistance. It drew global headlines – and whetted the public’s appetite for announcements of scientific breakthroughs that could cause economic transformations.

But like fusion, superconductivity can only be achieved in mostly impractical circumstances: It must operate either at temperatures of at least negative 100 degrees Fahrenheit, or under pressures of around 150,000 pounds per square inch. Superconductivity that functions in closer to a normal environment would cut energy costs dramatically while also opening infinite possibilities for computing, space travel and other applications.

In July, a group of South Korean scientists posted material claiming they had created an iron crystalline substance called LK-99 that could achieve superconductivity at slightly above room temperature and at ambient pressure. The group partners with the Quantum Energy Research Centre, a privately-held enterprise in Seoul, and their claims drew global headlines.

Their work was also debunked. But in the age of internet and social media, the process was compressed from half-a-year into days. And it did not require researchers at world-class universities.

One of the most compelling critiques came from Derrick VanGennep. Although he works in finance, he holds a Ph.D. in physics and held a postdoctoral position at Harvard. The South Korean researchers had posted a video of a nugget of LK-99 in what they claimed was the throes of the Meissner effect – an expulsion of the substance’s magnetic field that would cause it to levitate above a magnet. Unless Hollywood magic is involved, only superconducting material can hover in this manner.

That claim made VanGennep skeptical, particularly since LK-99’s levitation appeared unenthusiastic at best. In fact, a corner of the material still adhered to the magnet near its center. He thought the video demonstrated ferromagnetism – two magnets repulsing one another. He mixed powdered graphite with super glue, stuck iron filings to its surface and mimicked the behavior of LK-99 in his own video, which was posted alongside the researchers’ video.

VanGennep believes the boldness of the South Korean claim was what led to him and others in the scientific community questioning it so quickly.

“The swift replication attempts stemmed from the combination of the extreme claim, the fact that the synthesis for this material is very straightforward and fast, and the amount of attention that this story was getting on social media,” he says.

But practicing scientists were suspicious of the data as well. Michael Norman, director of the Argonne Quantum Institute at the Argonne National Laboratory just outside of Chicago, had doubts immediately.

Will this saga hurt or even affect the careers of the South Korean researchers? Possibly not, if the previous fusion example is any indication.

“It wasn’t a very polished paper,” Norman says of the Korean scientists’ work. That opinion was reinforced, he adds, when it turned out the paper had been posted online by one of the researchers prior to seeking publication in a peer-reviewed journal. Although Norman and Mathur say that is routine with scientific research these days, Norman notes it was posted by one of the junior researchers over the doubts of two more senior scientists on the project.

Norman also raises doubts about the data reported. Among other issues, he observes that the samples created by the South Korean researchers contained traces of copper sulfide that could inadvertently amplify findings of conductivity.

The lack of the Meissner effect also caught Mathur’s attention. “Ferromagnets tend to be unstable when they levitate,” he says, adding that the video “just made me feel unconvinced. And it made me feel like they hadn't made a very good case for themselves.”

Will this saga hurt or even affect the careers of the South Korean researchers? Possibly not, if the previous fusion example is any indication. Despite being debunked, cold fusion claimants Pons and Fleischmann didn’t disappear. They moved their research to automaker Toyota’s IMRA laboratory in France, which along with the Japanese government spent tens of millions of dollars on their work before finally pulling the plug in 1998.

Fusion has since been created in laboratories, but being unable to reproduce the density of a star’s core would require excruciatingly high temperatures to achieve – about 160 million degrees Fahrenheit. A recently released Government Accountability Office report concludes practical fusion likely remains at least decades away.

However, like Pons and Fleischman, the South Korean researchers are not going anywhere. They claim that LK-99’s Meissner effect is being obscured by the fact the substance is both ferromagnetic and diamagnetic. They have filed for a patent in their country. But for now, those claims remain chimerical.

In the meantime, the consensus as to when a room temperature superconductor will be achieved is mixed. VenGennep – who studied the issue during his graduate and postgraduate work – puts the chance of creating such a superconductor by 2050 at perhaps 50-50. Mathur believes it could happen sooner, but adds that research on the topic has been going on for nearly a century, and that it has seen many plateaus.

“There's always this possibility that there's going to be something out there that we're going to discover unexpectedly,” Norman notes. The only certainty in this age of social media is that it will be put through the rigors of replication instantly.

Scientists implant brain cells to counter Parkinson's disease

In a recent research trial, patients with Parkinson's disease reported that their symptoms had improved after stem cells were implanted into their brains. Martin Taylor, far right, was diagnosed at age 32.

Martin Taylor was only 32 when he was diagnosed with Parkinson's, a disease that causes tremors, stiff muscles and slow physical movement - symptoms that steadily get worse as time goes on.

“It's horrible having Parkinson's,” says Taylor, a data analyst, now 41. “It limits my ability to be the dad and husband that I want to be in many cruel and debilitating ways.”

Today, more than 10 million people worldwide live with Parkinson's. Most are diagnosed when they're considerably older than Taylor, after age 60. Although recent research has called into question certain aspects of the disease’s origins, Parkinson’s eventually kills the nerve cells in the brain that produce dopamine, a signaling chemical that carries messages around the body to control movement. Many patients have lost 60 to 80 percent of these cells by the time they are diagnosed.

For years, there's been little improvement in the standard treatment. Patients are typically given the drug levodopa, a chemical that's absorbed by the brain’s nerve cells, or neurons, and converted into dopamine. This drug addresses the symptoms but has no impact on the course of the disease as patients continue to lose dopamine producing neurons. Eventually, the treatment stops working effectively.

BlueRock Therapeutics, a cell therapy company based in Massachusetts, is taking a different approach by focusing on the use of stem cells, which can divide into and generate new specialized cells. The company makes the dopamine-producing cells that patients have lost and inserts these cells into patients' brains. “We have a disease with a high unmet need,” says Ahmed Enayetallah, the senior vice president and head of development at BlueRock. “We know [which] cells…are lost to the disease, and we can make them. So it really came together to use stem cells in Parkinson's.”

In a phase 1 research trial announced late last month, patients reported that their symptoms had improved after a year of treatment. Brain scans also showed an increased number of neurons generating dopamine in patients’ brains.

Increases in dopamine signals

The recent phase 1 trial focused on deploying BlueRock’s cell therapy, called bemdaneprocel, to treat 12 patients suffering from Parkinson’s. The team developed the new nerve cells and implanted them into specific locations on each side of the patient's brain through two small holes in the skull made by a neurosurgeon. “We implant cells into the places in the brain where we think they have the potential to reform the neural networks that are lost to Parkinson's disease,” Enayetallah says. The goal is to restore motor function to patients over the long-term.

Five patients were given a relatively low dose of cells while seven got higher doses. Specialized brain scans showed evidence that the transplanted cells had survived, increasing the overall number of dopamine producing cells. The team compared the baseline number of these cells before surgery to the levels one year later. “The scans tell us there is evidence of increased dopamine signals in the part of the brain affected by Parkinson's,” Enayetallah says. “Normally you’d expect the signal to go down in untreated Parkinson’s patients.”

"I think it has a real chance to reverse motor symptoms, essentially replacing a missing part," says Tilo Kunath, a professor of regenerative neurobiology at the University of Edinburgh.

The team also asked patients to use a specific type of home diary to log the times when symptoms were well controlled and when they prevented normal activity. After a year of treatment, patients taking the higher dose reported symptoms were under control for an average of 2.16 hours per day above their baselines. At the smaller dose, these improvements were significantly lower, 0.72 hours per day. The higher-dose patients reported a corresponding decrease in the amount of time when symptoms were uncontrolled, by an average of 1.91 hours, compared to 0.75 hours for the lower dose. The trial was safe, and patients tolerated the year of immunosuppression needed to make sure their bodies could handle the foreign cells.

Claire Bale, the associate director of research at Parkinson's U.K., sees the promise of BlueRock's approach, while noting the need for more research on a possible placebo effect. The trial participants knew they were getting the active treatment, and placebo effects are known to be a potential factor in Parkinson’s research. Even so, “The results indicate that this therapy produces improvements in symptoms for Parkinson's, which is very encouraging,” Bale says.

Tilo Kunath, a professor of regenerative neurobiology at the University of Edinburgh, also finds the results intriguing. “I think it's excellent,” he says. “I think it has a real chance to reverse motor symptoms, essentially replacing a missing part.” However, it could take time for this therapy to become widely available, Kunath says, and patients in the late stages of the disease may not benefit as much. “Data from cell transplantation with fetal tissue in the 1980s and 90s show that cells did not survive well and release dopamine in these [late-stage] patients.”

Searching for the right approach

There's a long history of using cell therapy as a treatment for Parkinson's. About four decades ago, scientists at the University of Lund in Sweden developed a method in which they transferred parts of fetal brain tissue to patients with Parkinson's so that their nerve cells would produce dopamine. Many benefited, and some were able to stop their medication. However, the use of fetal tissue was highly controversial at that time, and the tissues were difficult to obtain. Later trials in the U.S. showed that people benefited only if a significant amount of the tissue was used, and several patients experienced side effects. Eventually, the work lost momentum.

“Like many in the community, I'm aware of the long history of cell therapy,” says Taylor, the patient living with Parkinson's. “They've long had that cure over the horizon.”

In 2000, Lorenz Studer led a team at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Centre, in New York, to find the chemical signals needed to get stem cells to differentiate into cells that release dopamine. Back then, the team managed to make cells that produced some dopamine, but they led to only limited improvements in animals. About a decade later, in 2011, Studer and his team found the specific signals needed to guide embryonic cells to become the right kind of dopamine producing cells. Their experiments in mice, rats and monkeys showed that their implanted cells had a significant impact, restoring lost movement.

Studer then co-founded BlueRock Therapeutics in 2016. Forming the most effective stem cells has been one of the biggest challenges, says Enayetallah, the BlueRock VP. “It's taken a lot of effort and investment to manufacture and make the cells at the right scale under the right conditions.” The team is now using cells that were first isolated in 1998 at the University of Wisconsin, a major advantage because they’re available in a virtually unlimited supply.

Other efforts underway

In the past several years, University of Lund researchers have begun to collaborate with the University of Cambridge on a project to use embryonic stem cells, similar to BlueRock’s approach. They began clinical trials this year.

A company in Japan called Sumitomo is using a different strategy; instead of stem cells from embryos, they’re reprogramming adults' blood or skin cells into induced pluripotent stem cells - meaning they can turn into any cell type - and then directing them into dopamine producing neurons. Although Sumitomo started clinical trials earlier than BlueRock, they haven’t yet revealed any results.

“It's a rapidly evolving field,” says Emma Lane, a pharmacologist at the University of Cardiff who researches clinical interventions for Parkinson’s. “But BlueRock’s trial is the first full phase 1 trial to report such positive findings with stem cell based therapies.” The company’s upcoming phase 2 research will be critical to show how effectively the therapy can improve disease symptoms, she added.

The cure over the horizon

BlueRock will continue to look at data from patients in the phase 1 trial to monitor the treatment’s effects over a two-year period. Meanwhile, the team is planning the phase 2 trial with more participants, including a placebo group.

For patients with Parkinson’s like Martin Taylor, the therapy offers some hope, though Taylor recognizes that more research is needed.

BlueRock Therapeutics

“Like many in the community, I'm aware of the long history of cell therapy,” he says. “They've long had that cure over the horizon.” His expectations are somewhat guarded, he says, but, “it's certainly positive to see…movement in the field again.”

"If we can demonstrate what we’re seeing today in a more robust study, that would be great,” Enayetallah says. “At the end of the day, we want to address that unmet need in a field that's been waiting for a long time.”

Editor's note: The company featured in this piece, BlueRock Therapeutics, is a portfolio company of Leaps by Bayer, which is a sponsor of Leaps.org. BlueRock was acquired by Bayer Pharmaceuticals in 2019. Leaps by Bayer and other sponsors have never exerted influence over Leaps.org content or contributors.