This Special Music Helped Preemie Babies’ Brains Develop

Listening to music helped preterm babies' brains develop, according to the results of a new Swiss study.

Move over, Baby Einstein: New research from Switzerland shows that listening to soothing music in the first weeks of life helps encourage brain development in preterm babies.

For the study, the scientists recruited a harpist and a new-age musician to compose three pieces of music.

The Lowdown

Children who are born prematurely, between 24 and 32 weeks of pregnancy, are far more likely to survive today than they used to be—but because their brains are less developed at birth, they're still at high risk for learning difficulties and emotional disorders later in life.

Researchers in Geneva thought that the unfamiliar and stressful noises in neonatal intensive care units might be partially responsible. After all, a hospital ward filled with alarms, other infants crying, and adults bustling in and out is far more disruptive than the quiet in-utero environment the babies are used to. They decided to test whether listening to pleasant music could have a positive, counterbalancing effect on the babies' brain development.

Led by Dr. Petra Hüppi at the University of Geneva, the scientists recruited Swiss harpist and new-age musician Andreas Vollenweider (who has collaborated with the likes of Carly Simon, Bryan Adams, and Bobby McFerrin). Vollenweider developed three pieces of music specifically for the NICU babies, which were played for them five times per week. Each track was used for specific purposes: To help the baby wake up; to stimulate a baby who was already awake; and to help the baby fall back asleep.

When they reached an age equivalent to a full-term baby, the infants underwent an MRI. The researchers focused on connections within the salience network, which determines how relevant information is, and then processes and acts on it—crucial components of healthy social behavior and emotional regulation. The neural networks of preemies who had listened to Vollenweider's pieces were stronger than preterm babies who had not received the intervention, and were instead much more similar to full-term babies.

Next Up

The first infants in the study are now 6 years old—the age when cognitive problems usually become diagnosable. Researchers plan to follow up with more cognitive and socio-emotional assessments, to determine whether the effects of the music intervention have lasted.

The first infants in the study are now 6 years old—the age when cognitive problems usually become diagnosable.

The scientists note in their paper that, while they saw strong results in the babies' primary auditory cortex and thalamus connections—suggesting that they had developed an ability to recognize and respond to familiar music—there was less reaction in the regions responsible for socioemotional processing. They hypothesize that more time spent listening to music during a NICU stay could improve those connections as well; but another study would be needed to know for sure.

Open Questions

Because this initial study had a fairly small sample size (only 20 preterm infants underwent the musical intervention, with another 19 studied as a control group), and they all listened to the same music for the same amount of time, it's still undetermined whether variations in the type and frequency of music would make a difference. Are Vollenweider's harps, bells, and punji the runaway favorite, or would other styles of music help, too? (Would "Baby Shark" help … or hurt?) There's also a chance that other types of repetitive sounds, like parents speaking or singing to their children, might have similar effects.

But the biggest question is still the one that the scientists plan to tackle next: Whether the intervention lasts as the children grow up. If it does, that's great news for any family with a preemie — and for the baby-sized headphone industry.

New Tests Measure Your Body’s Biological Age, Offering a Glimpse into the Future of Health Care

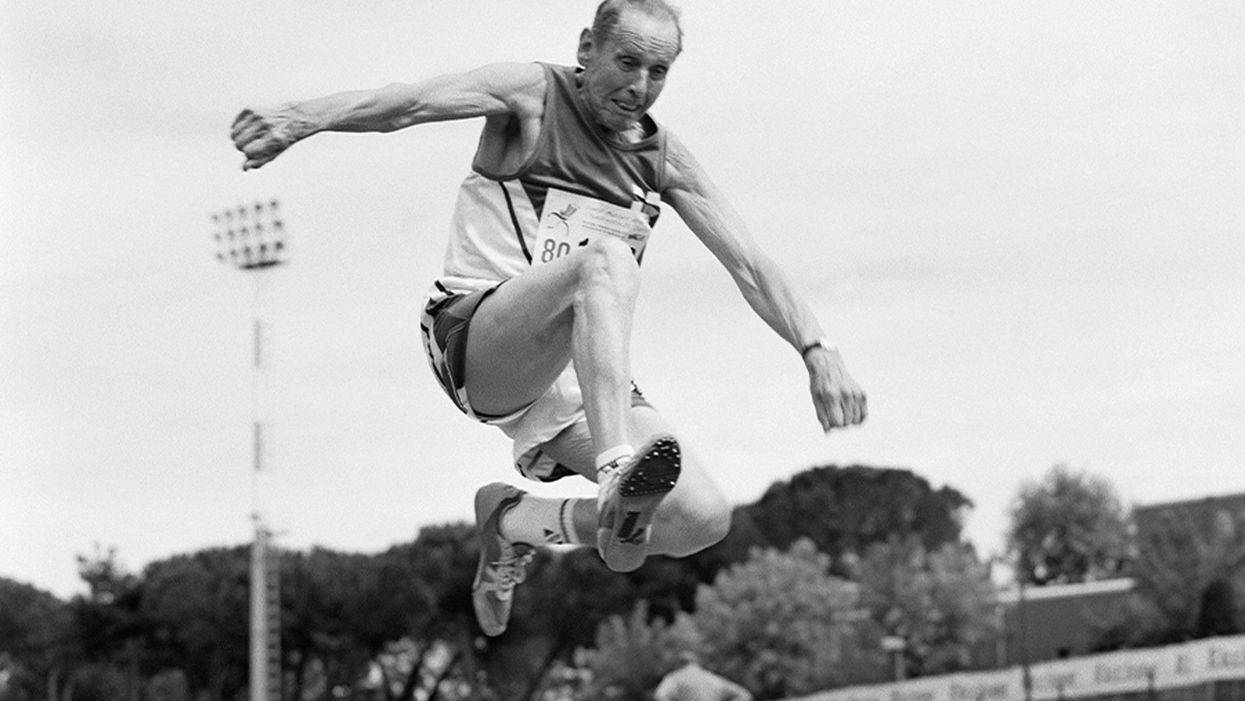

A senior long jumper competes in the 80-84-year-old age division at the 2007 World Masters Championships Stadia (track and field competition) at Riccione Stadium in Riccione, Italy on September 6, 2007. From the book project Racing Age.

What if a simple blood test revealed how fast you're aging, and this meant more to you and your insurance company than the number of candles on your birthday cake?

The question of why individuals thrive or decline has loomed large in 2020, with COVID-19 harming people of all ages, while leaving others asymptomatic. Meanwhile, scientists have produced new measures, called aging clocks, that attempt to predict mortality and may eventually affect how we perceive aging.

Take, for example, "senior" athletes who perform more like 50-year-olds. But people over 65 are lumped into one category, whether they are winning marathons or using a walker. Meanwhile, I'm entering "middle age," a label just as vague. It's frustrating to have a better grasp on the lifecycle of my phone than my own body.

That could change soon, due to clock technology. In 2013, UCLA biostatistician Steven Horvath took a new approach to an old carnival trick, guessing people's ages by looking at epigenetics: how chemical compounds in our cells turn genetic instructions on or off. Exercise, pollutants, and other aspects of lifestyle and environment can flip these switches, converting a skin cell into a hair cell, for example. Then, hair may sprout from your ears.

Horvath's epigenetic clock approximated age within just a few years; an above-average estimate suggested fast aging. This "basically changed everything," said Vadim Gladyshev, a Harvard geneticist, leading to more epigenetic clocks and, just since May, additional clocks of the heart, products of cell metabolism, and microbes in a person's mouth and gut.

Machine learning is fueling these discoveries. Scientists send algorithms hunting through jungles of health data for factors related to physical demise. "Nothing in [the aging] industry has progressed as much as biomarkers," said Alex Zhavoronkov, CEO of Deep Longevity, a pioneer in learning-based clocks.

Researchers told LeapsMag that this tech could help identify age-related vulnerabilities to diseases—including COVID-19—and protective drugs.

Clocking disease vulnerability

In July, Yale researcher Morgan Levine found people were more likely to be hospitalized and die from COVID-19 if their aging clocks were ticking ahead of their calendar years. This effect held regardless of pre-existing conditions.

The study used Levine's biological aging clock, called PhenoAge, which is more accurate than previous versions. To develop it, she looked at data on health indices over several decades, focusing on nine hallmarks of aging—such as inflammation—that correspond to when people die. Then she used AI to find which epigenetic patterns in blood samples were strongly associated with physical aging. The PhenoAge clock reads these patterns to predict biological age; mortality goes up 62 percent among the fastest agers.

The cocktail, aimed at restoring immune function, reversed age by an average of 2.5 years, according to an epigenetic clock measurement taken before and after the intervention.

Because PhenoAge links chronic inflammation to aging and vulnerability, Levine proposed treating "inflammaging" to counter COVID-19.

Gladyshev reported similar findings, and Nir Barzilai, director of the Institute of Aging Research at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, agreed that biological age deserves greater focus. PhenoAge is an important innovation, he said, but most precise when measuring average age across large populations. Until clocks—including his blood protein version—account for differences in how individuals age, "Multi-morbidity is really the major biomarker" for a given person. Barzilai thinks individuals over 65 with two or more diseases are biologically older than their chronological age—about half the population in this study.

He believes COVID-19 efforts aren't taking stock of these differences. "The scientists are living in silos," he said, with many unaware aging has a biology that can be targeted.

The missed opportunities could be profound, especially for lower-income communities with disproportionately advanced aging. Barzilai has read eight different observational studies finding decreased COVID-19 severity among people taking metformin, the diabetes drug, which is believed to slow down the major hallmarks of biological aging, such as inflammation. Once a vaccine is identified, biologically older people could supplement it with metformin, but the medical establishment requires lengthy clinical trials. "The conservatism is taking over in days of war," Barzilai said.

Drug benefits on time

Clocks, once validated, could gauge drug effectiveness against age-related diseases quicker and cheaper than trials that track health outcomes over many years, expediting FDA approval of such therapies. For this to happen, though, the FDA must see evidence that rewinding clocks or improving related biomarkers leads to clinical benefits for patients. Researchers believe that clinical applications for at least some of these clocks are five to 10 years away.

Progress was made in last year's TRIIM trial, run by immunologist Gregory Fahy at Stanford Medical Center. People in their 50s took growth hormone, metformin and another diabetes drug, dehydroepiandrosterone, for 12 months. The cocktail, aimed at restoring immune function, reversed age by an average of 2.5 years, according to an epigenetic clock measurement taken before and after the intervention. Don't quit your gym just yet; TRIIM included just nine Caucasian men. A follow-up with 85 diverse participants begins next month.

But even group averages of epigenetic measures can be questionable, explained Willard Freeman, a researcher with the Reynolds Oklahoma Center on Aging. Consider this odd finding: heroin addicts tend to have younger epigenetic ages. "With the exception of Keith Richards, I don't think heroin is a great way to live a long healthy life," Freeman said.

Such confounders reveal that scientists—and AI—are still struggling to unearth the roots of aging. Do clocks simply reflect damage, mirrors to show who's the frailest of them all? Or do they programmatically drive aging? The answer involves vast complexity, like trying to deduce the direct causes of a 17-car pileup on a potholed road in foggy conditions. Except, instead of 17 cars, it's millions of epigenetic sites and thousands of potential genes, RNA molecules and blood proteins acting on aging and each other.

Because the various measures—epigenetics, microbes, etc.—capture distinct aging dimensions, an important goal is unifying them into one "mosaic of biological ages," as Levine called it. Gladyshev said more datasets are needed. Just yesterday, though, Zhavoronkov launched Deep Longevity's groundbreaking composite of metrics to consumers – something that was previously available only to clinicians. The iPhone app allows users to upload their own samples and tracks aging on multiple levels – epigenetic, behavioral, microbiome, and more. It even includes a deep psychological clock asking if people feel as old as they are. Perhaps Twain's adage about mind over matter is evidence-backed.

Zhavoronkov appeared youthful in our Zoom interview, but admitted self-testing shows an advanced age because "I do not sleep"; indeed, he'd scheduled me at midnight Hong Kong time. Perhaps explaining his insomnia, he fears economic collapse if age-related diseases cost the global economy over $30 trillion by 2030. Rather than seeking eternal life, researchers like Zhavoronkov aim to increase health span: fully living our final decades without excess pain and hospital bills.

It's also a lucrative sales pitch to 7.8 billion aging humans.

Get your bio age

Levine, the Yale scientist, has partnered with Elysium Health to sell Index, an epigenetic measure launched in late 2019, direct to consumers, using their saliva samples. Elysium will roll out additional measures as research progresses, starting with an assessment of how fast someone is accumulating cells that no longer divide. "The more measures to capture specific processes, the more we can actually understand what's unique for an individual," Levine said.

Another company, InsideTracker, with an advisory board headlined by Harvard's David Sinclair, eschews the quirkiness of epigenetics. Its new InnerAge 2.0 test, announced this month, analyzes 18 blood biomarkers associated with longevity.

"You can imagine payers clamoring to charge people for costs with a kind of personal responsibility to them."

Because aging isn't considered a disease, consumer aging tests don't require FDA approval, and some researchers are skeptical of their use in the near future. "I'm on the fence as to whether these things are ready to be rolled out," said Freeman, the Oklahoma researcher. "We need to do our traditional experimental study design to [be] confident they're actually useful."

Then, 50-year-olds who are biologically 45 may wait five years for their first colonoscopy, Barzilai said. Despite some forerunners, clinical applications for individuals are mostly prospective, yet I was intrigued. Could these clocks reveal if I'm following the footsteps of the super-agers? Or will I rack up the hospital bills of Zhavoronkov's nightmares?

I sent my blood for testing with InsideTracker. Fearing the worst—an InnerAge accelerated by a couple of decades—I asked thought leaders where this technology is headed.

Insurance 2030

With continued advances, by 2030 you'll learn your biological age with a glance at your wristwatch. You won't be the only monitor; your insurance company may send an alert if your age goes too high, threatening lost rewards.

If this seems implausible, consider that life insurer John Hancock already tracks a VitalityAge. With Obamacare incentivizing companies to engage policyholders in improving health, many are dangling rewards for fitness. BlueCross BlueShield covers 25 percent of InsideTracker's cost, and UnitedHealthcare offers a suite of such programs, including "missions" for policyholders to lower their Rally age. "People underestimate the amount of time they're sedentary," said Michael Bess, vice president of healthcare strategies. "So having this technology to drive positive reinforcement is just another way to encourage healthy behavior."

It's unclear if these programs will close health gaps, or simply attract customers already prioritizing fitness. And insurers could raise your premium if you don't measure up. Obamacare forbids discrimination based on pre-existing conditions, but will accelerated age qualify for this protection?

Liz McFall, a sociologist at the University of Edinburgh, thinks the answer depends on whether we view aging as controllable. "You can imagine payers clamoring to charge people for costs with a kind of personal responsibility to them," she said.

That outcome troubles Mark Rothstein, director of the Institute of Bioethics at the University of Louisville. "For those living with air pollution and unsafe water, in food deserts and where you can't safely exercise, then [insurers] take the results in terms of biological stressors, now you're adding insult to injury," he said.

Government could subsidize aging clocks and interventions for older people with fewer resources for controlling their health—and the greatest room for improving their epigenetic age. Rothstein supports that policy, but said, "I don't see it happening."

Bio age working for you

2030 again. A job posting seeks a "go-getter," so you attach a doctor's note to your resume proving you're ten years younger than your chronological age.

This prospect intrigued Cathy Ventrell-Monsees, senior advisor at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. "Any marker other than age is a step forward," she said. "Age simply doesn't determine any kind of cognitive or physical ability."

What if the assessment isn't voluntary? Armed with AI, future employers could surveil a candidate's biological age from their head-shot. Haut.ai is already marketing an uncannily accurate PhotoAgeClock. Its CEO, Anastasia Georgievskaya, noted this tech's promise in other contexts; it could help people literally see the connection between healthier lifestyles and looking young and attractive. "The images keep people quite engaged," she told me.

Updating laws could minimize drawbacks. Employers are already prohibited from using genetic information to discriminate (think 23andMe). The ban could be extended to epigenetics. "I would imagine biomarkers for aging go a similar path as genetic nondiscrimination," said McFall, the sociologist.

Will we use aging clocks to screen candidates for the highest office? Barzilai, the Albert Einstein College of Medicine researcher, believes Trump and Biden have similar biological ages. But one of Barzilai's factors, BMI, is warped by Trump miraculously getting taller. "Usually people get shorter with age," Barzilai said. "His weight has been increasing, but his BMI stays the same."

As for my bio age? InnerAge suggested I'm four years younger—and by boosting my iron levels, the program suggests, I could be younger still.

We need standards for these tests, and customers must understand their shortcomings. With such transparency, though, the benefits could be compelling. In March, Theresa Brown, a 44-year-old from Kansas, learned her InnerAge was 57.2. She followed InsideTracker's recommendations, including regular intermittent fasting. Retested five months later, her age had dropped to 34.1. "It's not that I guaranteed another 10 or 20 years to my life. It's that it encourages me. Whether I really am or not, I just feel younger. I'll take that."

Which leads back to Zhavoronkov's psychological clock. Perhaps lowering our InnerAges can be the self-fulfilling prophesy that helps Theresa and me age like the super-athletes who thrive longer than expected. McFall noted the power of simple, sufficiently credible goals for encouraging better health. Think 10,000 steps per day, she said.

Want to be 34 again? Just do it.

Yet, many people's budgets just don't allow gym memberships, nutritious groceries, or futuristic aging clocks. Bill Gates cautioned we overestimate progress in the next two years, while underestimating the next ten. Policies should ensure that age testing and interventions are distributed fairly.

"Within the next 5 to 10 years," said Gladyshev, "there will be drugs and lifestyle changes which could actually increase lifespan or healthspan for the entire population."

How One University Is Successfully Tackling COVID-19

Alma Mater, a beloved bronze mother figure on the campus of the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana, wears a mask to encourage students to do the same as they return for the fall semester. Students are also expected to take a COVID-19 test twice a week.

China, South Korea and other places controlled the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic with the early use of strict lockdown and aggressive electronic contact tracing, monitoring, and enforcement.

The tussles in America over voluntary social distancing and wearing a mask in public suggest that more stringent enforcement methods adopted elsewhere would not work here. But one American university has emerged as a model of tough love pandemic management.

While many universities have become hot spots of COVID-19 infections this fall when students returned to campus, the University of Illinois was an exception. It has gotten the virus under control, at least for the moment, at a rate that is far below the national average and with minimal social disruption. Can the program they implemented work in our broader society?

The Illinois model is a comprehensive one which, as elsewhere, includes masking and social distancing, but it also requires a twice-weekly saliva test for SARS-CoV-2. All students and employees are assigned test days when they swipe their ID card and spit in a plastic tube, which is collected hourly and taken to a campus lab.

There a simplified but highly sensitive PCR genetic test goes through many cycles of amplifying the viral RNA. "Tracking three different viral RNA [genes] gives us very high accuracy," explains Martin Burke, the professor who developed the system and is monitoring its implementation at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. They immediately retest any positive sample to confirm the results, "So we think our false positive rate is extremely low. … The goal is to notify the positive person within 30 minutes of a positive test results becoming known."

Testing everyone so frequently, with a sensitive test that can quickly detect small amounts of the virus soon after infection, and isolating those who test positive before the virus can grow to volumes that make it very infectious helps the Illinois system break the chain of transmission.

"The testing we have done is not a silver bullet, it has to be done in combination with other mitigation measures. Our modeling shows that if you have masks, social distancing, and contact tracing you get a very dramatic, in fact synergistic effect with this combination,' says Burke. "So it really has to be a holistic approach with lots of community engagement in order to make this process successful."

The real teeth of enforcement are that people have to display their health status to gain access to campus facilities. A green check mark over their photo on a college ID phone app means they are good to go but a big red X means they are not current on their testing or have tested positive for the virus. Their ID is inactivated and they cannot enter campus facilities until they become compliant. Burke puts it bluntly; "We stop them from going where they want to go, a measure first used successfully with the pandemic in Wuhan, China.

He says they have learned from their experience and evolved their approach. "We never modeled for people who tested positive to ignore that result and go to or host parties, which could spread the infection." But several students did just that, and a few have been suspended for it.

So the university clamped down on enforcing isolation and now requires some higher risk persons to test three times a week to catch any infections earlier. Since more than 95 percent of new infections were among undergraduates, with no crossover from them to the local community, faculty, or graduate students, they have cut back testing of the latter two groups to just once a week.

About a thousand positive tests results have come back so far but no one has been hospitalized. Part of that likely is because the undergraduate population is largely young and healthy with few risk cofactors. But it may also be that with early identification and isolation, about five percent of dorm rooms have been set aside for that purpose, the person adopts healthier patterns of sleeping and eating that allows the immune system to better fight off the virus.

"But when you compare that to the being able to educate our students, perform research, keep our community thriving, our businesses open, if you add it all up, it's a tremendous return on investment."

The logistics are quite impressive for the campus that in ordinary times is home to more than 50,000 students; a lab capable of churning through 20,000 tests a day, with notification of results within hours, not days as is common elsewhere. And the results are equally impressive. The rate of positive test results blipped up to around 3 percent when undergraduates arrived back on campus but that has plummeted to 0.35 percent for the last seven-day period of testing, a tiny fraction of the rate for the nation as a whole. Much of it can be attributed to the closed environment with limited outside contact that might reintroduce the virus.

Still, even while the campus population has dropped by about a third, they are detecting about 250 new infections a week.

The threat of outside contact adding to the risk is why the university amended the undergraduate school calendar to close for Thanksgiving, hold final classes and exams for the semester online, and not return until February.

It doesn't come cheap. Burke estimates it cost $10 million to set up the program and about the same each semester to operate. "But when you compare that to the being able to educate our students, perform research, keep our community thriving, our businesses open, if you add it all up, it's a tremendous return on investment."

Burke acknowledges that they started with some significant advantages. The community is geographically isolated, an electronically linked ID system was already in place for students and employees, they have the ability to control much activity through access to buildings, and they can expel those who do not conform. He believes their system can translate to similar settings but admits, "A big city is very different from a university community." Still, he believes many of those lessons can be translated to different settings.

An alternative story

However, the situation is very different at the University of Colorado, where new infections have surged since undergraduates returned in late August. Administrators recently switched all classes to online only in an attempt to control the virus.

But that wasn't enough for state authorities who cracked down further, just yesterday declaring a two-week lockdown of all students aged 18 to 22, prohibiting gatherings of any size, indoors or out. Students must stay in their rooms except for essential activities, and if any symptoms develop, report for testing. Fraternities and sororities were targeted as past hot spots of infection.

The police will be actively enforcing the lockdown, and violators can face a penalty of up to 90 days in jail and a $1,000 fine.

Skepticism

Public health largely is based upon an appeal to self-interest and altruism, and voluntary compliance with official guidance. Harm reduction often comes into play when an ideal solution meets resistance and coercion plays only a limited role, as when a person with infectious tuberculosis is not compliant with treatment. Many question whether the medical threat of COVID-19 justifies such a sweeping restriction of individual rights of movement and association imposed on everyone simply because of their age and place of residence as is happening in Colorado.

State and federal courts have begun to strike down as an unconstitutional overreach some of the more restrictive decrees to stay at home or close businesses ordered by state and local officials. What was once tolerated as a few weeks or even a few months of restrictions now seems to stretch without an end in sight, and threatens peoples' livelihoods. In this litigious country it seems only a matter of time before someone will challenge some aspects of the Illinois model or similar programs being set up elsewhere as an infringement of their rights.

"I have real concerns about what we have seen over the course of the past several months in terms of going from not enough testing being available to now having more testing [available] because people don't want to be tested, even when they have symptoms," says Michael Osterholm, a noted expert on pandemic preparedness at the University of Minnesota. "We have some college campuses reporting over fifty percent of the students refusing to be tested or refusing to give any of the contacts that might be followed up on."

Often those who have tested positive for the virus "don't want people to know that they're the potential reason there could be an outbreak in their small social circle," says LaQuandra Nesbitt, public health director for Washington, DC. Stigma is one of the main reasons why only 37% of newly infected people have provided names for contact tracing in D.C., and few offer more than a single name.

"We can't test every single person every single day, we would completely go broke, we would be looking at no other health problems. We're not the NFL," says Monica Gandhi. She is a professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco and works closely with local health officials. "Just because we have a technology doesn't mean that we have to apply it for every purpose that may be indicated. … We would never dream of mass screening the public for influenza."

"Tests don't solve the problem," she argues. Masking is the most crucial piece for Gandhi, along with social distancing, washing hands regularly, and quarantine when testing positive or in contact with someone who is. Those are the actions that break the ongoing spread of transmission. She does support regular testing in high-risk settings such as nursing homes, inpatients in hospitals, and prisons, and periodic surveys in the general population to better understand where the virus is moving.

Drawing from experience with HIV, Gandhi worries that the stigma of a positive result will drive people away from testing. "Low-income persons will be particularly hesitant to get tested, or to share contact information if they do test positive, if they think they may have to quarantine, not work or gain income." That is why San Francisco initially assisted people in isolation with payment of $1285 for two weeks of isolation and other support as part of a right to health program. And this fall, the State of California passed legislation requiring that large businesses continue to pay employees in quarantine.

Tools for self-protection

The American temperament, decentralization, size, administrative complexity, and sheer cost make it highly unlikely that a coercive one-size-fits-all Illinois approach will ever be rolled out from a university campus to the entire nation. People make different decisions in trading off between safety and personal freedom or autonomy, and many are likely to embrace a rapid, inexpensive self-test if one becomes available, much like a home pregnancy test, to proactively monitor their own health.

OraSure Technologies pioneered the first home test for HIV. It is the only over-the-counter saliva test for HIV approved for sale in the U.S. Results show in about 20 minutes. The company went on to develop versions of this test for hepatitis C and Ebola. Thus it came as no surprise when in April the Department of Health and Human Services awarded it a $710 thousand contract to develop a rapid antigen home test for SARS-CoV-2.

Initial optimization studies for the antigen test showed that a nasal sample rather than an oral one generated better results, OraSure president and CEO Stephen Tang told LeapsMag. A test using a nasal swab is expected to be available later this year while work continues to develop an antibody test that uses saliva. He says, "the fundamental challenge is not only to develop the tests but to get it to scale quickly. That's the only way it's really going to matter." The company has manufacturing capacity to produce 35 million tests a year, with about half for SARS-CoV-2, and will double that capacity in steps within the next twelve months, with all of the increased capacity dedicated to COVID-19.

Initial use will be limited to health care workers and by prescription, but the company hopes to make it available over the counter soon after the FDA finalizes its rules on these types of tests for COVID-19. Importantly, OraSure believes its nasal swab test will be able to meet the current FDA standards for at-home tests. No such tests have yet been approved.

Tang says they envision using a phone app with the test, but that's tied to "the question of our century; who owns the data? If you are an individual buying the test, are you really compelled to report to anybody? If you are an employer and you buy the test and your employees take it, are you then entitled to the information because you're the one administering the test? That's all still being debated as well" by regulators, lawyers, and ethicists.

The price hasn't been set but Tang notes that they have "vast experience" in selling directly to the consumer, physicians, and public health systems in the U.S. and in lower-income companies. "We are very aware of what the economics are and what the need is today. We're trying to make this product as widely available to as many people as possible."

Another tool that may help protect the self-motivated are cell phone apps that alert you to potential exposure to others with the virus. Apple, Google and others have developed versions of the app that all work on the same principle and, miraculously, are compatible between the Apple and Android operating system universes. At first glance they look promising.

The glitch is that where they have been available the longest, only about 15-20 percent of users bother to download it, says Bennett Cyphers, a staff technologist with the Electronic Freedom Foundation (EFF), a nonprofit that advocates for privacy and other concerns in cyberspace. He explains, "If 1 in 10 people have the app installed, then only 1 in 100 interactions between everyone is going to be captured by the app. It scales that way; the fewer people you have, then a really, really small fraction of contacts are actually detected."

It is important to remember that much of public health is not the result of policy but of what people do in their daily lives.

Importantly, about 20 percent of Americans do not own a smart phone with the capacity to handle the app; that percentage is even higher among lower income, less educated, older folks who often are most at risk for suffering a severe case of COVID-19. So the value of this tool is likely to remain largely theoretical.

Divining the future

"It's tough to make predictions, especially about the future," the great baseball sage Yogi Berra is reported to have said. Will the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. follow the path of Illinois or Colorado?

The recent past often is no guide to such predictions. France, Spain, and Israel once earned plaudits for early and strict enforcement of lockdowns to control spread of the virus and then eased up on those restrictions. At the same time the world watched with condemnation and fascination as Sweden chose to follow a more laissez faire approach, urging voluntary distancing and masking but no major curtailing of activity.

Today the rates of new infections of COVID-19 in the first three countries have exploded to equal or multiples of the rate in Sweden. Which approach was the correct policy? Most people say it is still too early to tell for sure. The same can be said for the examples of Illinois and Colorado.

And then there is the puzzling example of Manaus, the Brazilian city of 1.8 million in the middle of the Amazon which was slammed with infections as hard as New York City; without the medical infrastructure to cope with the virus, 4000 have died. But then, suddenly, new infections began to taper off, and nobody claims to understand why, it certainly wasn't because official policies changed. One guess is that perhaps the region reached herd immunity, but that is simply speculation.

One can pick and choose examples of tough enforcement of quarantine or none to prove their point for the short term. But draconian measures will not be tolerated for long in a free society, and there is no clear, overwhelming evidence that over the long run one policy approach works better than another.

It is important to remember that much of public health is not the result of policy but of what people do in their daily lives. We have come remarkably far in what is still only months since we first heard the name of the virus. Death rates have fallen dramatically as we have learned how to better manage severe disease, often by adapting treatments for other diseases. And there is reason for optimism with the large number of vaccine candidates already in human trials.

We also have learned that we can control much of our own fate through simple but concerted actions in our daily lives such as social distancing, wearing masks, and washing hands. Let's not only remember those facts, but practice them.