Three Big Biotech Ideas to Watch in 2020—And Beyond

Body-on-a-chip, prime editing, and gut microbes all are poised to make a big impact in 2020.

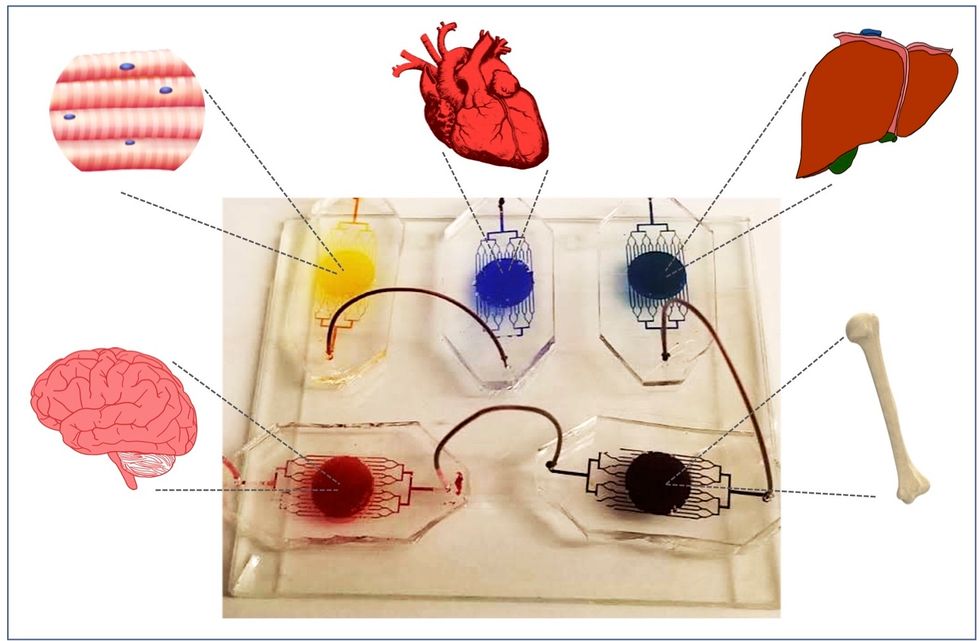

1. Happening Now: Body-on-a-Chip Technology Is Enabling Safer Drug Trials and Better Cancer Research

Researchers have increasingly used the technology known as "lab-on-a-chip" or "organ-on-a-chip" to test the effects of pharmaceuticals, toxins, and chemicals on humans. Rather than testing on animals, which raises ethical concerns and can sometimes be inaccurate, and human-based clinical trials, which can be expensive and difficult to iterate, scientists turn to tiny, micro-engineered chips—about the size of a thumb drive.

It's possible that doctors could one day take individual cell samples and create personalized treatments, testing out any medications on the chip.

The chips are lined with living samples of human cells, which mimic the physiology and mechanical forces experienced by cells inside the human body, down to blood flow and breathing motions; the functions of organs ranging from kidneys and lungs to skin, eyes, and the blood-brain barrier.

A more recent—and potentially even more useful—development takes organ-on-a-chip technology to the next level by integrating several chips into a "body-on-a-chip." Since human organs don't work in isolation, seeing how they all react—and interact—once a foreign element has been introduced can be crucial to understanding how a certain treatment will or won't perform. Dr. Shyni Varghese, a MEDx investigator at the Duke University School of Medicine, is one of the researchers working with these systems in order to gain a more nuanced understanding of how multiple different organs react to the same stimuli.

Her lab is working on "tumor-on-a-chip" models, which can not only show the progression and treatment of cancer, but also model how other organs would react to immunotherapy and other drugs. "The effect of drugs on different organs can be tested to identify potential side effects," Varghese says. In addition, these models can help the researchers figure out how cancers grow and spread, as well as how to effectively encourage immune cells to move in and attack a tumor.

One body-on-a-chip used by Dr. Varghese's lab tracks the interactions of five organs—brain, heart, liver, muscle, and bone.

As their research progresses, Varghese and her team are looking for ways to maintain the long-term function of the engineered organs. In addition, she notes that this kind of research is not just useful for generalized testing; "organ-on-chip technologies allow patient-specific analyses, which can be used towards a fundamental understanding of disease progression," Varghese says. It's possible that doctors could one day take individual cell samples and create personalized treatments, testing out any medications on the chip for safety, efficacy, and potential side effects before writing a prescription.

2. Happening Soon: Prime Editing Will Have the Power to "Find and Replace" Disease-Causing Genes

Biochemist David Liu made industry-wide news last fall when he and his lab at MIT's Broad Institute, led by Andrew Anzalone, published a paper on prime editing: a new, more focused technology for editing genes. Prime editing is a descendant of the CRISPR-Cas9 system that researchers have been working with for years, and a cousin to Liu's previous innovation—base editing, which can make a limited number of changes to a single DNA letter at a time.

By contrast, prime editing has the potential to make much larger insertions and deletions; it also doesn't require the tweaked cells to divide in order to write the changes into the DNA, which could make it especially suitable for central nervous system diseases, like Parkinson's.

Crucially, the prime editing technique has a much higher efficiency rate than the older CRISPR system, and a much lower incidence of accidental insertions or deletions, which can make dangerous changes for a patient.

It also has a very broad potential range: according to Liu, 89% of the pathogenic mutations that have been collected in ClinVar (a public archive of human variations) could, in principle, be treated with prime editing—although he is careful to note that correcting a single genetic mutation may not be sufficient to fully treat a genetic disease.

Figuring out just how prime editing can be used most effectively and safely will be a long process, but it's already underway. The same day that Liu and his team posted their paper, they also made the basic prime editing constructs available for researchers around the world through Addgene, a plasmid repository, so that others in the scientific community can test out the technique for themselves. It might be years before human patients will see the results, and in the meantime, significant bioethical questions remain about the limits and sociological effects of such a powerful gene-editing tool. But in the long fight against genetic diseases, it's a huge step forward.

3. Happening When We Fund It: Focusing on Microbiome Health Could Help Us Tackle Social Inequality—And Vice Versa

The past decade has seen a growing awareness of the major role that the microbiome, the microbes present in our digestive tract, play in human health. Having a less-healthy microbiome is correlated with health risks like diabetes and depression, and interventions that target gut health, ranging from kombucha to fecal transplants, have cropped up with increasing frequency.

New research from the University of Maine's Dr. Suzanne Ishaq takes an even broader view, arguing that low-income and disadvantaged populations are less likely to have healthy, diverse gut bacteria, and that increasing access to beneficial microorganisms is an important juncture of social justice and public health.

"Basically, allowing people to lead healthy lives allows them to access and recruit microbes."

"Typically, having a more diverse bacterial community is associated with health, and having fewer different species is associated with illness and may leave you open to infection from bacteria that are good at exploiting opportunities," Ishaq says.

Having a healthy biome doesn't mean meeting one fixed ratio of gut bacteria, since different combinations of microbes can generate roughly similar results when they work in concert. Generally, "good" microbes are the ones that break down fiber and create the byproducts that we use for energy, or ones like lactic acid bacteria that work to make microbials and keep other bacteria in check. The microbial universe in your gut is chaotic, Ishaq says. "Microbes in your gut interact with each other, with you, with your food, or maybe they don't interact at all and pass right through you." Overall, it's tricky to name specific microbial communities that will make or break someone's health.

There are important corollaries between environment and biome health, though, which Ishaq points out: Living in urban environments reduces microbial exposure, and losing the microorganisms that humans typically source from soil and plants can reduce our adaptive immunity and ability to fight off conditions like allergies and asthma. Access to green space within cities can counteract those effects, but in the U.S. that access varies along income, education, and racial lines. Likewise, lower-income communities are more likely to live in food deserts or areas where the cheapest, most convenient food options are monotonous and low in fiber, further reducing microbial diversity.

Ishaq also suggests other areas that would benefit from further study, like the correlation between paid family leave, breastfeeding, and gut microbiota. There are technical and ethical challenges to direct experimentation with human populations—but that's not what Ishaq sees as the main impediment to future research.

"The biggest roadblock is money, and the solution is also money," she says. "Basically, allowing people to lead healthy lives allows them to access and recruit microbes."

That means investment in things we already understand to improve public health, like better education and healthcare, green space, and nutritious food. It also means funding ambitious, interdisciplinary research that will investigate the connections between urban infrastructure, housing policy, social equity, and the millions of microbes keeping us company day in and day out.

A robot server, controlled remotely by a disabled worker, delivers drinks to patrons at the DAWN cafe in Tokyo.

A sleek, four-foot tall white robot glides across a cafe storefront in Tokyo’s Nihonbashi district, holding a two-tiered serving tray full of tea sandwiches and pastries. The cafe’s patrons smile and say thanks as they take the tray—but it’s not the robot they’re thanking. Instead, the patrons are talking to the person controlling the robot—a restaurant employee who operates the avatar from the comfort of their home.

It’s a typical scene at DAWN, short for Diverse Avatar Working Network—a cafe that launched in Tokyo six years ago as an experimental pop-up and quickly became an overnight success. Today, the cafe is a permanent fixture in Nihonbashi, staffing roughly 60 remote workers who control the robots remotely and communicate to customers via a built-in microphone.

More than just a creative idea, however, DAWN is being hailed as a life-changing opportunity. The workers who control the robots remotely (known as “pilots”) all have disabilities that limit their ability to move around freely and travel outside their homes. Worldwide, an estimated 16 percent of the global population lives with a significant disability—and according to the World Health Organization, these disabilities give rise to other problems, such as exclusion from education, unemployment, and poverty.

These are all problems that Kentaro Yoshifuji, founder and CEO of Ory Laboratory, which supplies the robot servers at DAWN, is looking to correct. Yoshifuji, who was bedridden for several years in high school due to an undisclosed health problem, launched the company to help enable people who are house-bound or bedridden to more fully participate in society, as well as end the loneliness, isolation, and feelings of worthlessness that can sometimes go hand-in-hand with being disabled.

“It’s heartbreaking to think that [people with disabilities] feel they are a burden to society, or that they fear their families suffer by caring for them,” said Yoshifuji in an interview in 2020. “We are dedicating ourselves to providing workable, technology-based solutions. That is our purpose.”

Shota, Kuwahara, a DAWN employee with muscular dystrophy, agrees. "There are many difficulties in my daily life, but I believe my life has a purpose and is not being wasted," he says. "Being useful, able to help other people, even feeling needed by others, is so motivational."

A woman receives a mammogram, which can detect the presence of tumors in a patient's breast.

When a patient is diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer, having surgery to remove the tumor is considered the standard of care. But what happens when a patient can’t have surgery?

Whether it’s due to high blood pressure, advanced age, heart issues, or other reasons, some breast cancer patients don’t qualify for a lumpectomy—one of the most common treatment options for early-stage breast cancer. A lumpectomy surgically removes the tumor while keeping the patient’s breast intact, while a mastectomy removes the entire breast and nearby lymph nodes.

Fortunately, a new technique called cryoablation is now available for breast cancer patients who either aren’t candidates for surgery or don’t feel comfortable undergoing a surgical procedure. With cryoablation, doctors use an ultrasound or CT scan to locate any tumors inside the patient’s breast. They then insert small, needle-like probes into the patient's breast which create an “ice ball” that surrounds the tumor and kills the cancer cells.

Cryoablation has been used for decades to treat cancers of the kidneys and liver—but only in the past few years have doctors been able to use the procedure to treat breast cancer patients. And while clinical trials have shown that cryoablation works for tumors smaller than 1.5 centimeters, a recent clinical trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York has shown that it can work for larger tumors, too.

In this study, doctors performed cryoablation on patients whose tumors were, on average, 2.5 centimeters. The cryoablation procedure lasted for about 30 minutes, and patients were able to go home on the same day following treatment. Doctors then followed up with the patients after 16 months. In the follow-up, doctors found the recurrence rate for tumors after using cryoablation was only 10 percent.

For patients who don’t qualify for surgery, radiation and hormonal therapy is typically used to treat tumors. However, said Yolanda Brice, M.D., an interventional radiologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, “when treated with only radiation and hormonal therapy, the tumors will eventually return.” Cryotherapy, Brice said, could be a more effective way to treat cancer for patients who can’t have surgery.

“The fact that we only saw a 10 percent recurrence rate in our study is incredibly promising,” she said.