To Make Science Engaging, We Need a Sesame Street for Adults

A new kind of television series could establish the baseline narratives for novel science like gene editing, quantum computing, or artificial intelligence.

This article is part of the magazine, "The Future of Science In America: The Election Issue," co-published by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD.

In the mid-1960s, a documentary producer in New York City wondered if the addictive jingles, clever visuals, slogans, and repetition of television ads—the ones that were captivating young children of the time—could be harnessed for good. Over the course of three months, she interviewed educators, psychologists, and artists, and the result was a bonanza of ideas.

Perhaps a new TV show could teach children letters and numbers in short animated sequences? Perhaps adults and children could read together with puppets providing comic relief and prompting interaction from the audience? And because it would be broadcast through a device already in almost every home, perhaps this show could reach across socioeconomic divides and close an early education gap?

Soon after Joan Ganz Cooney shared her landmark report, "The Potential Uses of Television in Preschool Education," in 1966, she was prototyping show ideas, attracting funding from The Carnegie Corporation, The Ford Foundation, and The Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and co-founding the Children's Television Workshop with psychologist Lloyd Morrisett. And then, on November 10, 1969, informal learning was transformed forever with the premiere of Sesame Street on public television.

For its first season, Sesame Street won three Emmy Awards and a Peabody Award. Its star, Big Bird, landed on the cover of Time Magazine, which called the show "TV's gift to children." Fifty years later, it's hard to imagine an approach to informal preschool learning that isn't Sesame Street.

And that approach can be boiled down to one word: Entertainment.

Despite decades of evidence from Sesame Street—one of the most studied television shows of all time—and more research from social science, psychology, and media communications, we haven't yet taken Ganz Cooney's concepts to heart in educating adults. Adults have news programs and documentaries and educational YouTube channels, but no Sesame Street. So why don't we? Here's how we can design a new kind of television to make science engaging and accessible for a public that is all too often intimidated by it.

We have to start from the realization that America is a nation of high-school graduates. By the end of high school, students have decided to abandon science because they think it's too difficult, and as a nation, we've made it acceptable for any one of us to say "I'm not good at science" and offload thinking to the ones who might be. So, is it surprising that a large number of Americans are likely to believe in conspiracy theories like the 25% that believe the release of COVID-19 was planned, the one in ten who believe the Moon landing was a hoax, or the 30–40% that think the condensation trails of planes are actually nefarious chemtrails? If we're meeting people where they are, the aim can't be to get the audience from an A to an A+, but from an F to a D, and without judgment of where they are starting from.

There's also a natural compulsion for a well-meaning educator to fill a literacy gap with a barrage of information, but this is what I call "factsplaining," and we know it doesn't work. And worse, it can backfire. In one study from 2014, parents were provided with factual information about vaccine safety, and it was the group that was already the most averse to vaccines that uniquely became even more averse.

Why? Our social identities and cognitive biases are stubborn gatekeepers when it comes to processing new information. We filter ideas through pre-existing beliefs—our values, our religions, our political ideologies. Incongruent ideas are rejected. Congruent ideas, no matter how absurd, are allowed through. We hear what we want to hear, and then our brains justify the input by creating narratives that preserve our identities. Even when we have all the facts, we can use them to support any worldview.

But social science has revealed many mechanisms for hijacking these processes through narrative storytelling, and this can form the foundation of a new kind of educational television.

Could new television series establish the baseline narratives for novel science like gene editing, quantum computing, or artificial intelligence?

As media creators, we can reject factsplaining and instead construct entertaining narratives that disrupt cognitive processes. Two-decade-old research tells us when people are immersed in entertaining fiction narratives, they loosen their defenses, opening a path for new information, editing attitudes, and inspiring new behavior. Where news about hot-button issues like climate change or vaccination might trigger resistance or a backfire effect, fiction can be crafted to be absorbing and, as a result, persuasive.

But the narratives can't be stuffed with information. They must be simplified. If this feels like the opposite of what an educator should be doing, it is possible to reduce the complexity of information, without oversimplification, through "exemplification," a framing device to tell the stories of individuals in specific circumstances that can speak to the greater issue without needing to explain it all. It's a technique you've seen used in biopics. The Discovery Channel true-crime miniseries Manhunt: Unabomber does many things well from a science storytelling perspective, including exemplifying the virtues of the scientific method through a character who argues for a new field of science, forensic linguistics, to catch one of the most notorious domestic terrorists in U.S. history.

We must also appeal to the audience's curiosity. We know curiosity is such a strong driver of human behavior that it can even counteract the biases put up by one's political ideology around subjects like climate change. If we treat science information like a product—and we should—advertising research tells us we can maximize curiosity though a Goldilocks effect. If the information is too complex, your show might as well be a PowerPoint presentation. If it's too simple, it's Sesame Street. There's a sweet spot for creating intrigue about new information when there's a moderate cognitive gap.

The science of "identification" tells us that the more the main character is endearing to a viewer, the more likely the viewer will adopt the character's worldview and journey of change. This insight further provides incentives to craft characters reflective of our audiences. If we accept our biases for what they are, we can understand why the messenger becomes more important than the message, because, without an appropriate messenger, the message becomes faint and ineffective. And research confirms that the stereotype-busting doctor-skeptic Dana Scully of The X-Files, a popular science-fiction series, was an inspiration for a generation of women who pursued science careers.

With these directions, we can start making a new kind of television. But is television itself still the right delivery medium? Americans do spend six hours per day—a quarter of their lives—watching video. And even with the rise of social media and apps, science-themed television shows remain popular, with four out of five adults reporting that they watch shows about science at least sometimes. CBS's The Big Bang Theory was the most-watched show on television in the 2017–2018 season, and Cartoon Network's Rick & Morty is the most popular comedy series among millennials. And medical and forensic dramas continue to be broadcast staples. So yes, it's as true today as it was in the 1980s when George Gerbner, the "cultivation theory" researcher who studied the long-term impacts of television images, wrote, "a single episode on primetime television can reach more people than all science and technology promotional efforts put together."

We know from cultivation theory that media images can shape our views of scientists. Quick, picture a scientist! Was it an old, white man with wild hair in a lab coat? If most Americans don't encounter research science firsthand, it's media that dictates how we perceive science and scientists. Characters like Sheldon Cooper and Rick Sanchez become the model. But we can correct that by representing professionals more accurately on-screen and writing characters more like Dana Scully.

Could new television series establish the baseline narratives for novel science like gene editing, quantum computing, or artificial intelligence? Or could new series counter the misinfodemics surrounding COVID-19 and vaccines through more compelling, corrective narratives? Social science has given us a blueprint suggesting they could. Binge-watching a show like the surreal NBC sitcom The Good Place doesn't replace a Ph.D. in philosophy, but its use of humor plants the seed of continued interest in a new subject. The goal of persuasive entertainment isn't to replace formal education, but it can inspire, shift attitudes, increase confidence in the knowledge of complex issues, and otherwise prime viewers for continued learning.

[Editor's Note: To read other articles in this special magazine issue, visit the beautifully designed e-reader version.]

New Podcast: Why Dr. Ashish Jha Expects a Good Summer

Dr. Jha discusses Covid vaccine passports, how supply and demand of the vaccines is about to shift, the AstraZeneca situation, what's new with kids, herd immunity, and more.

Making Sense of Science features interviews with leading medical and scientific experts about the latest developments and the big ethical and societal questions they raise. This monthly podcast is hosted by journalist Kira Peikoff, founding editor of the award-winning science outlet Leaps.org.

Hear the 30-second trailer:

Listen to the whole episode: "Why Dr. Ashish Jha Expects a Good Summer"

Dr. Ashish Jha, dean of public health at Brown University, discusses the latest developments around the Covid-19 vaccines, including supply and demand, herd immunity, kids, vaccine passports, and why he expects the summer to look very good.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

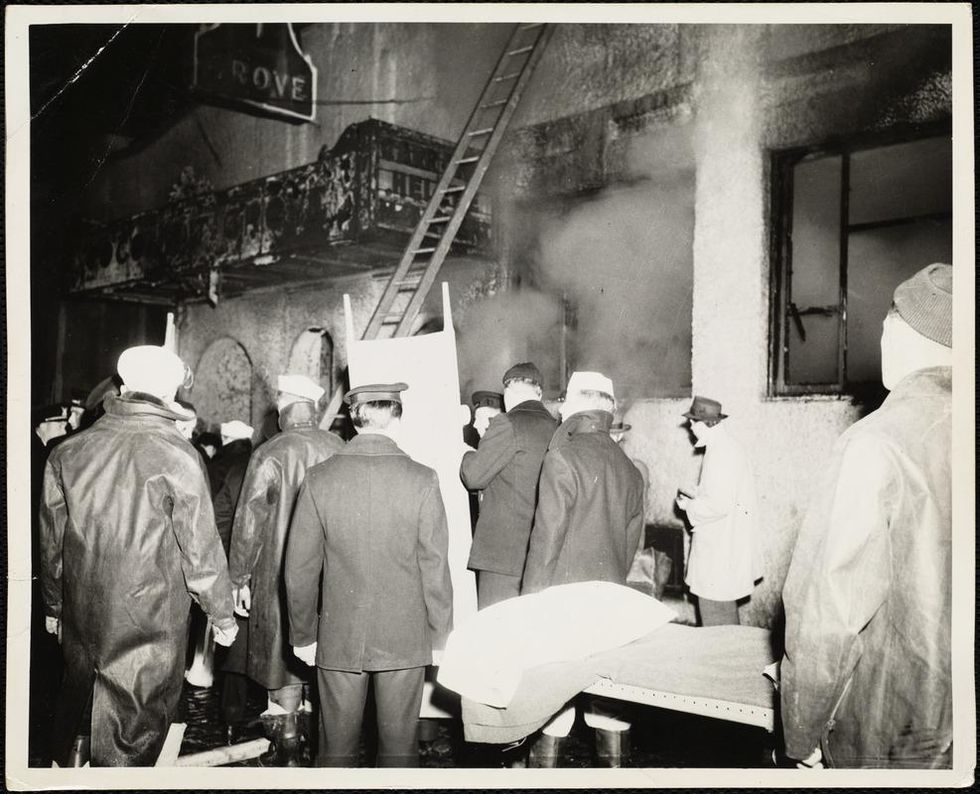

How a Deadly Fire Gave Birth to Modern Medicine

The Cocoanut Grove fire in Boston in 1942 tragically claimed 490 lives, but was the catalyst for several important medical advances.

On the evening of November 28, 1942, more than 1,000 revelers from the Boston College-Holy Cross football game jammed into the Cocoanut Grove, Boston's oldest nightclub. When a spark from faulty wiring accidently ignited an artificial palm tree, the packed nightspot, which was only designed to accommodate about 500 people, was quickly engulfed in flames. In the ensuing panic, hundreds of people were trapped inside, with most exit doors locked. Bodies piled up by the only open entrance, jamming the exits, and 490 people ultimately died in the worst fire in the country in forty years.

"People couldn't get out," says Dr. Kenneth Marshall, a retired plastic surgeon in Boston and president of the Cocoanut Grove Memorial Committee. "It was a tragedy of mammoth proportions."

Within a half an hour of the start of the blaze, the Red Cross mobilized more than five hundred volunteers in what one newspaper called a "Rehearsal for Possible Blitz." The mayor of Boston imposed martial law. More than 300 victims—many of whom subsequently died--were taken to Boston City Hospital in one hour, averaging one victim every eleven seconds, while Massachusetts General Hospital admitted 114 victims in two hours. In the hospitals, 220 victims clung precariously to life, in agonizing pain from massive burns, their bodies ravaged by infection.

The scene of the fire.

Boston Public Library

Tragic Losses Prompted Revolutionary Leaps

But there is a silver lining: this horrific disaster prompted dramatic changes in safety regulations to prevent another catastrophe of this magnitude and led to the development of medical techniques that eventually saved millions of lives. It transformed burn care treatment and the use of plasma on burn victims, but most importantly, it introduced to the public a new wonder drug that revolutionized medicine, midwifed the birth of the modern pharmaceutical industry, and nearly doubled life expectancy, from 48 years at the turn of the 20th century to 78 years in the post-World War II years.

The devastating grief of the survivors also led to the first published study of post-traumatic stress disorder by pioneering psychiatrist Alexandra Adler, daughter of famed Viennese psychoanalyst Alfred Adler, who was a student of Freud. Dr. Adler studied the anxiety and depression that followed this catastrophe, according to the New York Times, and "later applied her findings to the treatment World War II veterans."

Dr. Ken Marshall is intimately familiar with the lingering psychological trauma of enduring such a disaster. His mother, an Irish immigrant and a nurse in the surgical wards at Boston City Hospital, was on duty that cold Thanksgiving weekend night, and didn't come home for four days. "For years afterward, she'd wake up screaming in the middle of the night," recalls Dr. Marshall, who was four years old at the time. "Seeing all those bodies lined up in neat rows across the City Hospital's parking lot, still in their evening clothes. It was always on her mind and memories of the horrors plagued her for the rest of her life."

The sheer magnitude of casualties prompted overwhelmed physicians to try experimental new procedures that were later successfully used to treat thousands of battlefield casualties. Instead of cutting off blisters and using dyes and tannic acid to treat burned tissues, which can harden the skin, they applied gauze coated with petroleum jelly. Doctors also refined the formula for using plasma--the fluid portion of blood and a medical technology that was just four years old--to replenish bodily liquids that evaporated because of the loss of the protective covering of skin.

"Every war has given us a new medical advance. And penicillin was the great scientific advance of World War II."

"The initial insult with burns is a loss of fluids and patients can die of shock," says Dr. Ken Marshall. "The scientific progress that was made by the two institutions revolutionized fluid management and topical management of burn care forever."

Still, they could not halt the staph infections that kill most burn victims—which prompted the first civilian use of a miracle elixir that was being secretly developed in government-sponsored labs and that ultimately ushered in a new age in therapeutics. Military officials quickly realized this disaster could provide an excellent natural laboratory to test the effectiveness of this drug and see if it could be used to treat the acute traumas of combat in this unfortunate civilian approximation of battlefield conditions. At the time, the very existence of this wondrous medicine—penicillin—was a closely guarded military secret.

From Forgotten Lab Experiment to Wonder Drug

In 1928, Alexander Fleming discovered the curative powers of penicillin, which promised to eradicate infectious pathogens that killed millions every year. But the road to mass producing enough of the highly unstable mold was littered with seemingly unsurmountable obstacles and it remained a forgotten laboratory curiosity for over a decade. But Fleming never gave up and penicillin's eventual rescue from obscurity was a landmark in scientific history.

In 1940, a group at Oxford University, funded in part by the Rockefeller Foundation, isolated enough penicillin to test it on twenty-five mice, which had been infected with lethal doses of streptococci. Its therapeutic effects were miraculous—the untreated mice died within hours, while the treated ones played merrily in their cages, undisturbed. Subsequent tests on a handful of patients, who were brought back from the brink of death, confirmed that penicillin was indeed a wonder drug. But Britain was then being ravaged by the German Luftwaffe during the Blitz, and there were simply no resources to devote to penicillin during the Nazi onslaught.

In June of 1941, two of the Oxford researchers, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, embarked on a clandestine mission to enlist American aid. Samples of the temperamental mold were stored in their coats. By October, the Roosevelt Administration had recruited four companies—Merck, Squibb, Pfizer and Lederle—to team up in a massive, top-secret development program. Merck, which had more experience with fermentation procedures, swiftly pulled away from the pack and every milligram they produced was zealously hoarded.

After the nightclub fire, the government ordered Merck to dispatch to Boston whatever supplies of penicillin that they could spare and to refine any crude penicillin broth brewing in Merck's fermentation vats. After working in round-the-clock relays over the course of three days, on the evening of December 1st, 1942, a refrigerated truck containing thirty-two liters of injectable penicillin left Merck's Rahway, New Jersey plant. It was accompanied by a convoy of police escorts through four states before arriving in the pre-dawn hours at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dozens of people were rescued from near-certain death in the first public demonstration of the powers of the antibiotic, and the existence of penicillin could no longer be kept secret from inquisitive reporters and an exultant public. The next day, the Boston Globe called it "priceless" and Time magazine dubbed it a "wonder drug."

Within fourteen months, penicillin production escalated exponentially, churning out enough to save the lives of thousands of soldiers, including many from the Normandy invasion. And in October 1945, just weeks after the Japanese surrender ended World War II, Alexander Fleming, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain were awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine. But penicillin didn't just save lives—it helped build some of the most innovative medical and scientific companies in history, including Merck, Pfizer, Glaxo and Sandoz.

"Every war has given us a new medical advance," concludes Marshall. "And penicillin was the great scientific advance of World War II."