Top Fertility Doctor: Artificially Created Sperm and Eggs "Will Become Normal" One Day

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

A rendering of in vitro fertilization.

Imagine two men making a baby. Or two women. Or an infertile couple. Or an older woman whose eggs are no longer viable. None of these people could have a baby today without the help of an egg or sperm donor.

Cells scraped from the inside of your cheek could one day be manipulated to become either eggs or sperm.

But in the future, it may be possible for them to reproduce using only their own genetic material, thanks to an emerging technology called IVG, or in vitro gametogenesis.

Researchers are learning how to reprogram adult human cells like skin cells to become lab-created egg and sperm cells, which could then be joined to form an embryo. In other words, cells scraped from the inside of your cheek could one day be manipulated to become either eggs or sperm, no matter your gender or your reproductive fitness.

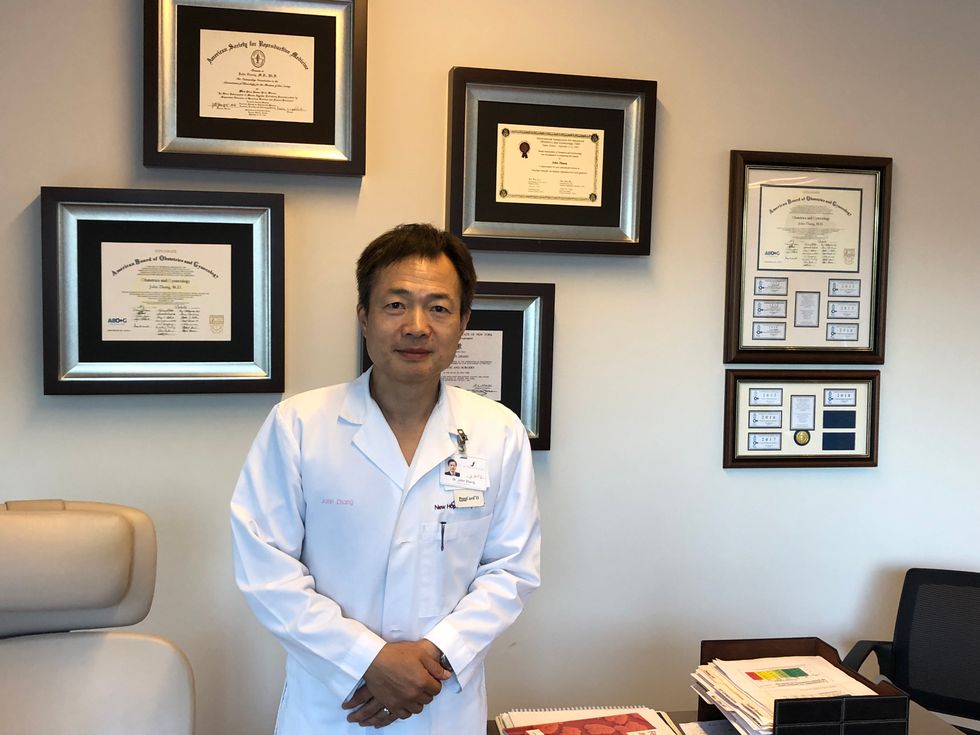

In 2016, Japanese scientists proved that the concept could be successfully carried out in mice. Now some experts, like Dr. John Zhang, the founder and CEO of New Hope Fertility Center in Manhattan, say it's just "a matter of time" before the method is also made to work in humans.

Such a technological tour de force would upend our most basic assumptions about human reproduction and biology. Combined with techniques like gene editing, these tools could eventually enable prospective parents to have an unprecedented level of choice and control over their children's origins. It's a wildly controversial notion, and an especially timely one now that a Chinese scientist has announced the birth of the first allegedly CRISPR-edited babies. (The claims remain unverified.)

Zhang himself is no stranger to controversy. In 2016, he stunned the world when he announced the birth of a baby conceived using the DNA of three people, a landmark procedure intended to prevent the baby from inheriting a devastating neurological disease. (Zhang went to a clinic in Mexico to carry out the procedure because it is prohibited in the U.S.) Zhang's other achievements to date include helping a 49-year-old woman have a baby using her own eggs and restoring a young woman's fertility through an ovarian tissue transplant surgery.

Zhang recently sat down with our Editor-in-Chief in his New York office overlooking Columbus Circle to discuss the fertility world's latest provocative developments. Here are his top ten insights:

Clearly [gene-editing embryos] will be beneficial to mankind, but it's a matter of how and when the work is done.

1) On a Chinese scientist's claim of creating the first CRISPR-edited babies:

I'm glad that we made a first move toward a clinical application of this technology for mankind. Somebody has to do this. Whether this was a good case or not, there is still time to find out.

Clearly it will be beneficial to mankind, but it's a matter of how and when the work is done. Like any scientific advance, it has to be done in a very responsible way.

Today's response is identical to when the world's first IVF baby was announced in 1978. The major news media didn't take it seriously and thought it was evil, wanted to keep a distance from IVF. Many countries even abandoned IVF, but today you see it is a normal practice. And it took almost 40 years [for the researchers] to win a Nobel Prize.

I think we need more time to understand how this work was done medically, ethically, and let the scientist have the opportunity to present how it was done and let a scientific journal publish the paper. Before these become available, I don't think we should start being upset, scared, or giving harsh criticism.

2) On the international outcry in response to the news:

I feel we are in scientific shock, with many thinking it came too fast, too soon. We all embrace modern technology, but when something really comes along, we fear it. In an old Chinese saying, one of the masters always dreamed of seeing the dragon, and when the dragon really came, he got scared.

Dr. John Zhang, the founder and CEO of New Hope Fertility Center in Manhattan, pictured in his office.

3) On the Western world's perception that Chinese scientists sometimes appear to discount ethics in favor of speedy breakthroughs:

I think this perception is not fair. I don't think China is very casual. It's absolutely not what people think. I don't want people to feel that this case [of CRISPR-edited babies] will mean China has less standards over how human reproduction should be performed. Just because this happened, it doesn't mean in China you can do anything you want.

As far as the regulation of IVF clinics, China is probably the most strictly regulated of any country I know in this world.

4) On China's first public opinion poll gauging attitudes toward gene-edited babies, indicating that more than 60 percent of survey respondents supported using the technology to prevent inherited diseases, but not to enhance traits:

There is a sharp contrast between the general public and the professional world. Being a working health professional and an advocate of scientists working in this field, it is very important to be ethically responsible for what we are doing, but my own feeling is that from time to time we may not take into consideration what the patient needs.

5) On how the three-parent baby is doing today, several years after his birth:

No news is good news.

6) On the potentially game-changing research to develop artificial sperm and eggs:

First of all I think that anything that's technically possible, as long as you are not harmful to other people, to other societies, as long as you do it responsibly, and this is a legitimate desire, I think eventually it will become reality.

My research for now is really to try to overcome the very next obstacle in our field, which is how to let a lady age 44 or older have a baby with her own genetic material.

Practically 99 percent of women over age 43 will never make a baby on their own. And after age 47, we usually don't offer donor egg IVF anymore.

But with improved longevity, and quality of life, the lifespan of females continues to increase. In Japan, the average for females is about 89 years old. So for more than half of your life, you will not be able to produce a baby, which is quite significant in the animal kingdom. In most of the animal kingdom, their reproductive life is very much the same as their life, but then you can argue in the animal kingdom unlike a human being, it doesn't take such a long time for them to contribute to the society because once you know how to hunt and look for food, you're done.

"I think this will become a major ethical debate: whether we should let an older lady have a baby at a very late state of her life."

But humans are different. You need to go to college, get certain skills. It takes 20 years to really bring a human being up to become useful to society. That's why the mom and dad are not supposed to have the same reproductive life equal to their real life.

I think this will become a major ethical debate: whether we should let an older lady have a baby at a very late state of her life and leave the future generation in a very vulnerable situation in which they may lack warm caring, proper guidance, and proper education.

7) On using artificial gametes to grant more reproductive choices to gays and lesbians:

I think it is totally possible to have two sperm make a baby, and two eggs make babies.

If we have two guys, one guy to produce eggs, or two girls, one would have to become sperm. Basically you are creating artificial gametes or converting with gametes from sperm to become egg or egg to become a sperm. Which may not necessarily be very difficult. The key is to be able to do nuclear reprogramming.

So why can two sperm not make offspring now? You get exactly half of your genes from each parent. The genes have their own imprinting that say "made in mom," "made in dad." The two sperm would say "made in dad," "made in dad." If I can erase the "made in dad," and say "made in mom," then these sperm can make offspring.

8) On how close science is to creating artificial gametes for clinical use in pregnancies:

It's very hard to say until we accomplish it. It could be very quick. It could be it takes a long time. I don't want to speculate.

"I think these technologies are the solid foundation just like when we designed the computer -- we never thought a computer would become the iPhone."

9) On whether there should be ethical red lines drawn by authorities or whether the decisions should be left to patients and scientists:

I think we cannot believe a hundred percent in the scientist and the patient but it should not be 100 percent authority. It should be coming from the whole of society.

10) On his expectations for the future:

We are living in a very exciting world. I think that all these technologies can really change the way of mankind and also are not just for baby-making. The research, the experience, the mechanism we learn from these technologies, they will shine some great lights into our long-held dream of being a healthy population that is cancer-free and lives a long life, let's say 120 years.

I think these technologies are the solid foundation just like when we designed the computer -- we never thought a computer would become the iPhone. Imagine making a computer 30 years ago, that this little chip will change your life.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

A new injection is helping stave off RSV this season

The FDA approved a single-dose, long-acting injection to protect babies and toddlers from RSV over the fall and winter.

In November 2021, Mickayla Wininger’s then one-month-old son, Malcolm, endured a terrifying bout with RSV, the respiratory syncytial (sin-SISH-uhl) virus—a common ailment that affects all age groups. Most people recover from mild, cold-like symptoms in a week or two, but RSV can be life-threatening in others, particularly infants.

Wininger, who lives in southern Illinois, was dressing Malcolm for bed when she noticed what seemed to be a minor irregularity with this breathing. She and her fiancé, Gavin McCullough, planned to take him to the hospital the next day. The matter became urgent when, in the morning, the boy’s breathing appeared to have stopped.

After they dialed 911, Malcolm started breathing again, but he ended up being hospitalized three times for RSV and defects in his heart. Eventually, he recovered fully from RSV, but “it was our worst nightmare coming to life,” Wininger recalled.

It’s a scenario that the federal government is taking steps to prevent. In July, the Food and Drug Administration approved a single-dose, long-acting injection to protect babies and toddlers. The injection, called Beyfortus, or nirsevimab, became available this October. It reduces the incidence of RSV in pre-term babies and other infants for their first RSV season. Children at highest risk for severe RSV are those who were born prematurely and have either chronic lung disease of prematurity or congenital heart disease. In those cases, RSV can progress to lower respiratory tract diseases such as pneumonia and bronchiolitis, or swelling of the lung’s small airway passages.

Each year, RSV is responsible for 2.1 million outpatient visits among children younger than five-years-old, 58,000 to 80,000 hospitalizations in this age group, and between 100 and 300 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Transmitted through close contact with an infected person, the virus circulates on a seasonal basis in most regions of the country, typically emerging in the fall and peaking in the winter.

In August, however, the CDC issued a health advisory on a late-summer surge in severe cases of RSV among young children in Florida and Georgia. The agency predicts "increased RSV activity spreading north and west over the following two to three months.”

Infants are generally more susceptible to RSV than older people because their airways are very small, and their mechanisms to clear these passages are underdeveloped. RSV also causes mucus production and inflammation, which is more of a problem when the airway is smaller, said Jennifer Duchon, an associate professor of newborn medicine and pediatrics in the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York.

In 2021 and 2022, RSV cases spiked, sending many to emergency departments. “RSV can cause serious disease in infants and some children and results in a large number of emergency department and physician office visits each year,” John Farley, director of the Office of Infectious Diseases in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a news release announcing the approval of the RSV drug. The decision “addresses the great need for products to help reduce the impact of RSV disease on children, families and the health care system.”

Sean O’Leary, chair of the committee on infectious diseases for the American Academy of Pediatrics, says that “we’ve never had a product like this for routine use in children, so this is very exciting news.” It is recommended for all kids under eight months old for their first RSV season. “I would encourage nirsevimab for all eligible children when it becomes available,” O’Leary said.

For those children at elevated risk of severe RSV and between the ages of 8 and 19 months, the CDC recommends one dose in their second RSV season.

The drug will be “really helpful to keep babies healthy and out of the hospital,” said O’Leary, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus/Children’s Hospital Colorado in Denver.

An antiviral drug called Synagis (palivizumab) has been an option to prevent serious RSV illness in high-risk infants since it was approved by the FDA in 1998. The injection must be given monthly during RSV season. However, its use is limited to “certain children considered at high risk for complications, does not help cure or treat children already suffering from serious RSV disease, and cannot prevent RSV infection,” according to the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

Until the approval this summer of the new monoclonal antibody, nirsevimab, there wasn’t a reliable method to prevent infection in most healthy infants.

Both nirsevimab and palivizumab are monoclonal antibodies that act against RSV. Monoclonal antibodies are lab-made proteins that mimic the immune system’s ability to fight off harmful pathogens such as viruses. A single intramuscular injection of nirsevimab preceding or during RSV season may provide protection.

The strategy with the new monoclonal antibody is “to extend protection to healthy infants who nonetheless are at risk because of their age, as well as infants with additional medical risk factors,” said Philippa Gordon, a pediatrician and infectious disease specialist in Brooklyn, New York, and medical adviser to Park Slope Parents, an online community support group.

No specific preventive measure is needed for older and healthier kids because they will develop active immunity, which is more durable. Meanwhile, older adults, who are also vulnerable to RSV, can receive one of two new vaccines. So can pregnant women, who pass on immunity to the fetus, Gordon said.

Until the approval this summer of the new monoclonal antibody, nirsevimab, there wasn’t a reliable method to prevent infection in most healthy infants, “nor is there any treatment other than giving oxygen or supportive care,” said Stanley Spinner, chief medical officer and vice president of Texas Children’s Pediatrics and Texas Children’s Urgent Care.

As with any virus, washing hands frequently and keeping infants and children away from sick people are the best defenses, Duchon said. This approach isn’t foolproof because viruses can run rampant in daycare centers, schools and parents’ workplaces, she added.

Mickayla Wininger, Malcolm’s mother, insists that family and friends wear masks, wash their hands and use hand sanitizer when they’re around her daughter and two sons. She doesn’t allow them to kiss or touch the children. Some people take it personally, but she would rather be safe than sorry.

Wininger recalls the severe anxiety caused by Malcolm's ordeal with RSV. After returning with her infant from his hospital stays, she was terrified to go to sleep. “My fiancé and I would trade shifts, so that someone was watching over our son 24 hours a day,” she said. “I was doing a night shift, so I would take caffeine pills to try and keep myself awake and would end up crashing early hours in the morning and wake up frantically thinking something happened to my son.”

Two years later, her anxiety has become more manageable, and Malcolm is doing well. “He is thriving now,” Wininger said. He recently had his second birthday and "is just the spunkiest boy you will ever meet. He looked death straight in the eyes and fought to be here today.”

AI was integral to creating Moderna's mRNA vaccine against COVID.

Story by Big Think

For most of history, artificial intelligence (AI) has been relegated almost entirely to the realm of science fiction. Then, in late 2022, it burst into reality — seemingly out of nowhere — with the popular launch of ChatGPT, the generative AI chatbot that solves tricky problems, designs rockets, has deep conversations with users, and even aces the Bar exam.

But the truth is that before ChatGPT nabbed the public’s attention, AI was already here, and it was doing more important things than writing essays for lazy college students. Case in point: It was key to saving the lives of tens of millions of people.

AI-designed mRNA vaccines

As Dave Johnson, chief data and AI officer at Moderna, told MIT Technology Review‘s In Machines We Trust podcast in 2022, AI was integral to creating the company’s highly effective mRNA vaccine against COVID. Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech’s mRNA vaccines collectively saved between 15 and 20 million lives, according to one estimate from 2022.

Johnson described how AI was hard at work at Moderna, well before COVID arose to infect billions. The pharmaceutical company focuses on finding mRNA therapies to fight off infectious disease, treat cancer, or thwart genetic illness, among other medical applications. Messenger RNA molecules are essentially molecular instructions for cells that tell them how to create specific proteins, which do everything from fighting infection, to catalyzing reactions, to relaying cellular messages.

Johnson and his team put AI and automated robots to work making lots of different mRNAs for scientists to experiment with. Moderna quickly went from making about 30 per month to more than one thousand. They then created AI algorithms to optimize mRNA to maximize protein production in the body — more bang for the biological buck.

For Johnson and his team’s next trick, they used AI to automate science, itself. Once Moderna’s scientists have an mRNA to experiment with, they do pre-clinical tests in the lab. They then pore over reams of data to see which mRNAs could progress to the next stage: animal trials. This process is long, repetitive, and soul-sucking — ill-suited to a creative scientist but great for a mindless AI algorithm. With scientists’ input, models were made to automate this tedious process.

“We don’t think about AI in the context of replacing humans,” says Dave Johnson, chief data and AI officer at Moderna. “We always think about it in terms of this human-machine collaboration, because they’re good at different things. Humans are really good at creativity and flexibility and insight, whereas machines are really good at precision and giving the exact same result every single time and doing it at scale and speed.”

All these AI systems were in put in place over the past decade. Then COVID showed up. So when the genome sequence of the coronavirus was made public in January 2020, Moderna was off to the races pumping out and testing mRNAs that would tell cells how to manufacture the coronavirus’s spike protein so that the body’s immune system would recognize and destroy it. Within 42 days, the company had an mRNA vaccine ready to be tested in humans. It eventually went into hundreds of millions of arms.

Biotech harnesses the power of AI

Moderna is now turning its attention to other ailments that could be solved with mRNA, and the company is continuing to lean on AI. Scientists are still coming to Johnson with automation requests, which he happily obliges.

“We don’t think about AI in the context of replacing humans,” he told the Me, Myself, and AI podcast. “We always think about it in terms of this human-machine collaboration, because they’re good at different things. Humans are really good at creativity and flexibility and insight, whereas machines are really good at precision and giving the exact same result every single time and doing it at scale and speed.”

Moderna, which was founded as a “digital biotech,” is undoubtedly the poster child of AI use in mRNA vaccines. Moderna recently signed a deal with IBM to use the company’s quantum computers as well as its proprietary generative AI, MoLFormer.

Moderna’s success is encouraging other companies to follow its example. In January, BioNTech, which partnered with Pfizer to make the other highly effective mRNA vaccine against COVID, acquired the company InstaDeep for $440 million to implement its machine learning AI across its mRNA medicine platform. And in May, Chinese technology giant Baidu announced an AI tool that designs super-optimized mRNA sequences in minutes. A nearly countless number of mRNA molecules can code for the same protein, but some are more stable and result in the production of more proteins. Baidu’s AI, called “LinearDesign,” finds these mRNAs. The company licensed the tool to French pharmaceutical company Sanofi.

Writing in the journal Accounts of Chemical Research in late 2021, Sebastian M. Castillo-Hair and Georg Seelig, computer engineers who focus on synthetic biology at the University of Washington, forecast that AI machine learning models will further accelerate the biotechnology research process, putting mRNA medicine into overdrive to the benefit of all.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.