Debates over transgender athletes rage on, with new state bans and rules for Olympians, NCAA sports

Some argue that transgender females should be banned from competing with women in sports, while others think such bans are unfair, as the NCAA and other organizations try to keep up with research on how testosterone affects performance.

Ashley O’Connor, who was biologically male at birth but identifies as female, decided to compete in badminton as a girl during her senior year of high school in Downers Grove, Illinois. There was no team for boys, and a female friend and badminton player “practically bullied me into joining” the girls’ team. O’Connor, who is 18 and taking hormone replacement therapy for her gender transition, recalled that “it was easily one of the best decisions I have ever made.”

She believes there are many reasons why it’s important for transgender people to have the option of playing sports on the team of their choice. “It provides a sense of community,” said O’Connor, now a first-year student concentrating in psychology at the College of DuPage in Glen Ellyn, Illinois.

“It’s a great way to get a workout, which is good for physical and mental health,” she added. She also enjoyed the opportunity to be competitive, learn about her strengths and weaknesses, and just be normal. “Trans people have friends and trans people want to play sports with their friends, especially in adolescence,” she said.

However, in 18 states, many of which are politically conservative, laws prohibit transgender students from participating in sports consistent with their gender identity, according to the Movement Advancement Project, an independent, nonprofit think tank based in Boulder, Colo., that focuses on the rights of LGBTQ people. The first ban was passed in Idaho in 2020, although federal district judges have halted this legislation and a similar law in West Virginia from taking effect.

Proponents of the bans caution that transgender females would have an unfair biological advantage in competitive school sports with other girls or women as a result of being born as stronger males, potentially usurping the athletic accomplishments of other athletes.

“The future of women’s sports is at risk, and the equal rights of female athletes is being infringed,” said Penny Nance, CEO and president of Concerned Women for America, a legislative action committee in D.C. that seeks to impact culture to promote religious values.

“As the tidal wave of gender activism consumes sports from the Olympics on down, a backlash is being felt as parents are furious about the disregard for their daughters who have worked very hard to achieve success as athletes,” Nance added. “Former athletes, whose records are being shattered, are demanding answers.”

Meanwhile, opponents of the bans contend that they bar transgender athletes from playing sports with friends and learning the value of teamwork and other life lessons. These laws target transgender girls most often in kindergarten through high school but sometimes in college as well. Many local schools and state athletic associations already have their own guidelines “to both protect transgender people and ensure a level playing field for all athletes,” according to the Movement Advancement Project’s website. But statewide bans take precedence over these policies.

"It’s easy to sympathize on some level with arguments on both sides, and it’s likely going to be impossible to make everyone happy,” said Liz Joy, a past president of the American College of Sports Medicine.

In January, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), based in Indianapolis, tried to sort out the controversy by implementing a new policy. It requires transgender students participating in female sports to prove that they’ve been taking treatments to suppress testosterone for at least one year before competition, as well as demonstrating that their testosterone level is sufficiently low, depending on the sport, through a blood test.

Then, in August, the NCAA clarified that these athletes also must take another blood test six months after their season has started that shows their testosterone levels aren’t too high. Additional guidelines will take effect next August.

Even with these requirements, “there is no plan that is going to be considered equitable and fair to all,” said Bradley Anawalt, an endocrinologist at the University of Washington School of Medicine. Biologically, he noted, there is still some evidence that a transgender female who initiates hormone therapy with estrogen and drops her testosterone to very low levels may have some advantage over other females, based on characteristics such as hand and foot size, height and perhaps strength.

Liz Joy, a past president of the American College of Sports Medicine, agrees that allowing transgender athletes to compete on teams of their self-identifying gender poses challenges. “It’s easy to sympathize on some level with arguments on both sides, and it’s likely going to be impossible to make everyone happy,” said Joy, a physician and senior medical director of wellness and nutrition at Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, Utah. While advocating for inclusion, she added that “sport was incredibly important in my life. I just want everyone to be able to benefit from it.”

One solution may be to allow transgender youth to play sports in a way that aligns with their gender identity until a certain age and before an elite level. “There are minimal or no potential financial stakes for most youth sports before age 13 or 14, and you do not have a lot of separation in athlete performance between most boys and girls until about age 13,” said Anwalt, who was a reviewer of the Endocrine Society’s national guidelines on transgender care.

Myron Genel, a professor emeritus and former chief of pediatric endocrinology at Yale School of Medicine, said it’s difficult to argue that height gives transgender females an edge because in some sports tall women already dominate over their shorter counterparts.

He added that the decision to allow transgender females to compete with other girls or women could hinge on when athletes began taking testosterone blockers. “If the process of conversion from male to female has been undertaken in the early stages of puberty, from my perspective, they have very little unique advantage,” said Genel, who advised the International Olympic Committee (IOC), based in Switzerland, on testosterone limits for transgender athletes.

Because young athletes’ bodies are still developing, “the differences in natural abilities are so massive that they would overwhelm any advantage a transgender athlete might have,” said Thomas H. Murray, president emeritus of The Hastings Center, a pioneering bioethics research institute in Garrison, New York, and author of the book “Good Sport,” which focuses on the ethics and values in the Olympics and other competitions.

“There’s no good reason to limit the participation of transgender athletes in the sports where male athletes don’t have an advantage over women,” such as sailing, archery and shooting events, Murray said. “The burden of proof rests on those who want to restrict participation by transgender athletes. They must show that in this sport, at this level of competition, transgender athletes have a conspicuous advantage.”

Last year, the IOC issued a new framework emphasizing that the Olympic rules related to transgender participation should be specific to each sport. “This is an evolving topic and there has been—as it will continue to be—new research coming out and new developments informing our approach,” and there’s currently no consensus on how testosterone affects performance across all sports, an IOC spokesperson told Leaps.org.

Many of the new laws prohibiting transgender people from competing in sports consistent with their gender identity specifically apply to transgender females. Yet, some experts say the issue also affects transgender males, nonbinary and intersex athletes.

“There has been quite a bit of attention paid to transgender females and their participation in biological female sports and almost minimal focus on transgender male competition in male sports or in any sports,” said Katherine Drabiak, associate professor of public health law and medical ethics at University of South Florida in Tampa. In fact, “transgender men, because they were born female, would be at a disadvantage of having less lean body mass, less strength and less muscular area as a general category compared to a biological male.”

While discussing transgender students’ participation in sports, it’s important to call attention to the toll that anti-transgender legislation can take on these young people’s well-being, said Jonah DeChants, a research scientist at The Trevor Project, a suicide prevention and mental health organization for LGBTQ youth. Recent polling found that 85 percent of transgender and nonbinary youth said that debates around anti-transgender laws had a negative impact on their mental health.

“The reality is simple: Most transgender girls want to play sports for the same reasons as any student—to benefit their health, to have fun, and to build connection with friends,” DeChants said. According to a new peer-reviewed qualitative study by researchers at The Trevor Project, many trans girls who participated in sports experienced harassment and stigma based on their gender identity, which can contribute to poor mental health outcomes and suicide risk.

In addition to badminton, O'Connor played other sports such as volleyball, and she plans to become an assistant coach or manager of her old high school's badminton team.

Ashley O'Connor

However, DeChants added, research also shows that young people who reported living in an accepting community, had access to LGBTQ-affirming spaces, or had social support from family and friends reported significantly lower rates of attempting suicide in the past year. “We urge coaches, educators and school administrators to seek LGBTQ-cultural competency training, implement zero tolerance policies for anti-trans bullying, and create safe, affirming environments for all transgender students on and off the field,” DeChants said.

O’Connor said her experiences on the athletic scene have been mostly positive. The politics of her community lean somewhat liberal, and she thinks it’s probably more supportive than some other areas of the country, though she noted the local library has received threats for hosting LGBTQ events. In addition to badminton, she also played baseball, lacrosse, volleyball, basketball and hockey. In the spring, she plans to become an assistant coach or manager for the girls’ badminton team at her old high school.

“When I played badminton, I never got any direct backlash from any coaches, competitors or teammates,” she said. “I had a few other teammates that identified as trans or nonbinary, [and] nearly all of the people I ever interacted with were super pleasant and treated me like any other normal person.” She added that transgender athletes “have aspirations. We have wants and needs. We have dreams. And at the end of the day, we just want to live our lives and be happy like everyone else.”

Scientists turn pee into power in Uganda

With conventional fuel cells as their model, researchers learned to use similar chemical reactions to make a fuel from microbes in pee.

At the edge of a dirt road flanked by trees and green mountains outside the town of Kisoro, Uganda, sits the concrete building that houses Sesame Girls School, where girls aged 11 to 19 can live, learn and, at least for a while, safely use a toilet. In many developing regions, toileting at night is especially dangerous for children. Without electrical power for lighting, kids may fall into the deep pits of the latrines through broken or unsteady floorboards. Girls are sometimes assaulted by men who hide in the dark.

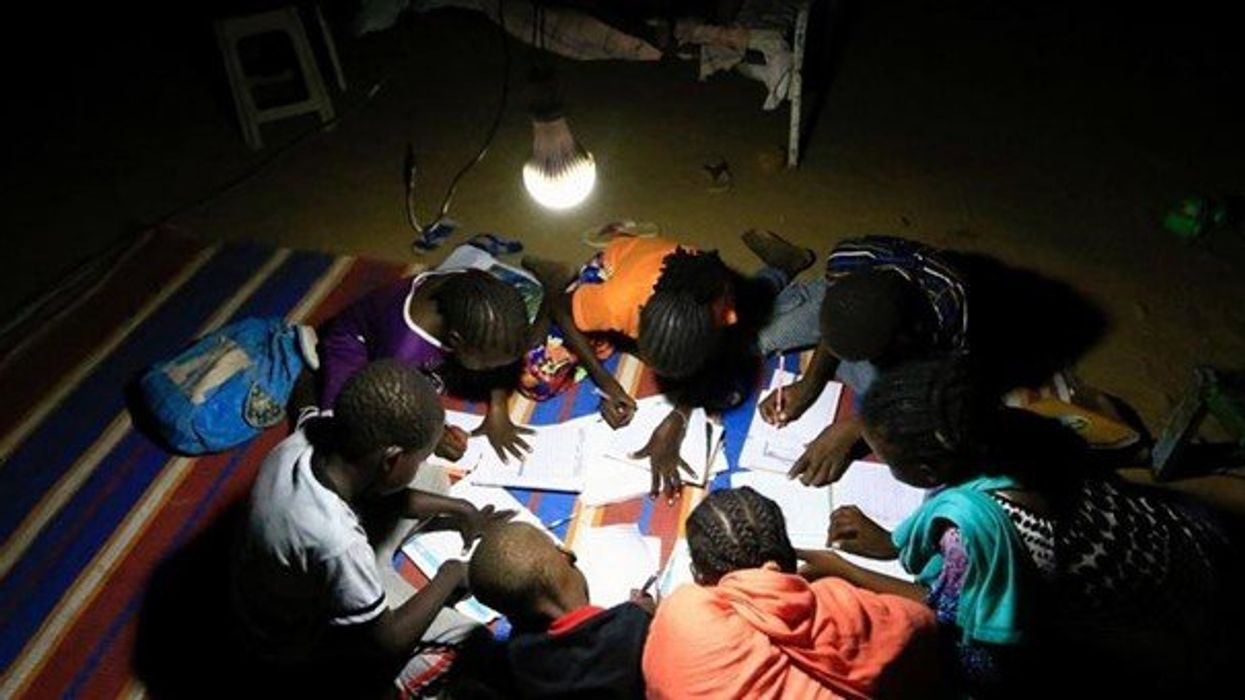

For the Sesame School girls, though, bright LED lights, connected to tiny gadgets, chased the fears away. They got to use new, clean toilets lit by the power of their own pee. Some girls even used the light provided by the latrines to study.

Urine, whether animal or human, is more than waste. It’s a cheap and abundant resource. Each day across the globe, 8.1 billion humans make 4 billion gallons of pee. Cows, pigs, deer, elephants and other animals add more. By spending money to get rid of it, we waste a renewable resource that can serve more than one purpose. Microorganisms that feed on nutrients in urine can be used in a microbial fuel cell that generates electricity – or "pee power," as the Sesame girls called it.

Plus, urine contains water, phosphorus, potassium and nitrogen, the key ingredients plants need to grow and survive. Human urine could replace about 25 percent of current nitrogen and phosphorous fertilizers worldwide and could save water for gardens and crops. The average U.S. resident flushes a toilet bowl containing only pee and paper about six to seven times a day, which adds up to about 3,500 gallons of water down per year. Plus cows in the U.S. produce 231 gallons of the stuff each year.

Pee power

A conventional fuel cell uses chemical reactions to produce energy, as electrons move from one electrode to another to power a lightbulb or phone. Ioannis Ieropoulos, a professor and chair of Environmental Engineering at the University of Southampton in England, realized the same type of reaction could be used to make a fuel from microbes in pee.

Bacterial species like Shewanella oneidensis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa can consume carbon and other nutrients in urine and pop out electrons as a result of their digestion. In a microbial fuel cell, one electrode is covered in microbes, immersed in urine and kept away from oxygen. Another electrode is in contact with oxygen. When the microbes feed on nutrients, they produce the electrons that flow through the circuit from one electrod to another to combine with oxygen on the other side. As long as the microbes have fresh pee to chomp on, electrons keep flowing. And after the microbes are done with the pee, it can be used as fertilizer.

These microbes are easily found in wastewater treatment plants, ponds, lakes, rivers or soil. Keeping them alive is the easy part, says Ieropoulos. Once the cells start producing stable power, his group sequences the microbes and keeps using them.

Like many promising technologies, scaling these devices for mass consumption won’t be easy, says Kevin Orner, a civil engineering professor at West Virginia University. But it’s moving in the right direction. Ieropoulos’s device has shrunk from the size of about three packs of cards to a large glue stick. It looks and works much like a AAA battery and produce about the same power. By itself, the device can barely power a light bulb, but when stacked together, they can do much more—just like photovoltaic cells in solar panels. His lab has produced 1760 fuel cells stacked together, and with manufacturing support, there’s no theoretical ceiling, he says.

Although pure urine produces the most power, Ieropoulos’s devices also work with the mixed liquids of the wastewater treatment plants, so they can be retrofit into urban wastewater utilities.

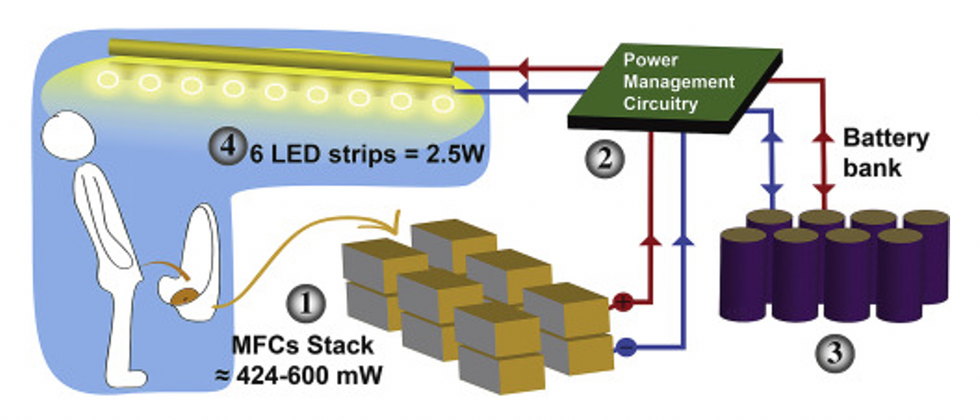

This image shows how the pee-powered system works. Pee feeds bacteria in the stack of fuel cells (1), which give off electrons (2) stored in parallel cylindrical cells (3). These cells are connected to a voltage regulator (4), which smooths out the electrical signal to ensure consistent power to the LED strips lighting the toilet.

Courtesy Ioannis Ieropoulos

Key to the long-term success of any urine reclamation effort, says Orner, is avoiding what he calls “parachute engineering”—when well-meaning scientists solve a problem with novel tech and then abandon it. “The way around that is to have either the need come from the community or to have an organization in a community that is committed to seeing a project operate and maintained,” he says.

Success with urine reclamation also depends on the economy. “If energy prices are low, it may not make sense to recover energy,” says Orner. “But right now, fertilizer prices worldwide are generally pretty high, so it may make sense to recover fertilizer and nutrients.” There are obstacles, too, such as few incentives for builders to incorporate urine recycling into new construction. And any hiccups like leaks or waste seepage will cost builders money and reputation. Right now, Orner says, the risks are just too high.

Despite the challenges, Ieropoulos envisions a future in which urine is passed through microbial fuel cells at wastewater treatment plants, retrofitted septic tanks, and building basements, and is then delivered to businesses to use as agricultural fertilizers. Although pure urine produces the most power, Ieropoulos’s devices also work with the mixed liquids of the wastewater treatment plants, so they can be retrofitted into urban wastewater utilities where they can make electricity from the effluent. And unlike solar cells, which are a common target of theft in some areas, nobody wants to steal a bunch of pee.

When Ieropoulos’s team returned to wrap up their pilot project 18 months later, the school’s director begged them to leave the fuel cells in place—because they made a major difference in students’ lives. “We replaced it with a substantial photovoltaic panel,” says Ieropoulos, They couldn’t leave the units forever, he explained, because of intellectual property reasons—their funders worried about theft of both the technology and the idea. But the photovoltaic replacement could be stolen, too, leaving the girls in the dark.

The story repeated itself at another school, in Nairobi, Kenya, as well as in an informal settlement in Durban, South Africa. Each time, Ieropoulos vowed to return. Though the pandemic has delayed his promise, he is resolute about continuing his work—it is a moral and legal obligation. “We've made a commitment to ourselves and to the pupils,” he says. “That's why we need to go back.”

Urine as fertilizer

Modern day industrial systems perpetuate the broken cycle of nutrients. When plants grow, they use up nutrients the soil. We eat the plans and excrete some of the nutrients we pass them into rivers and oceans. As a result, farmers must keep fertilizing the fields while our waste keeps fertilizing the waterways, where the algae, overfertilized with nitrogen, phosphorous and other nutrients grows out of control, sucking up oxygen that other marine species need to live. Few global communities remain untouched by the related challenges this broken chain create: insufficient clean water, food, and energy, and too much human and animal waste.

The Rich Earth Institute in Vermont runs a community-wide urine nutrient recovery program, which collects urine from homes and businesses, transports it for processing, and then supplies it as fertilizer to local farms.

One solution to this broken cycle is reclaiming urine and returning it back to the land. The Rich Earth Institute in Vermont is one of several organizations around the world working to divert and save urine for agricultural use. “The urine produced by an adult in one day contains enough fertilizer to grow all the wheat in one loaf of bread,” states their website.

Notably, while urine is not entirely sterile, it tends to harbor fewer pathogens than feces. That’s largely because urine has less organic matter and therefore less food for pathogens to feed on, but also because the urinary tract and the bladder have built-in antimicrobial defenses that kill many germs. In fact, the Rich Earth Institute says it’s safe to put your own urine onto crops grown for home consumption. Nonetheless, you’ll want to dilute it first because pee usually has too much nitrogen and can cause “fertilizer burn” if applied straight without dilution. Other projects to turn urine into fertilizer are in progress in Niger, South Africa, Kenya, Ethiopia, Sweden, Switzerland, The Netherlands, Australia, and France.

Eleven years ago, the Institute started a program that collects urine from homes and businesses, transports it for processing, and then supplies it as fertilizer to local farms. By 2021, the program included 180 donors producing over 12,000 gallons of urine each year. This urine is helping to fertilize hay fields at four partnering farms. Orner, the West Virginia professor, sees it as a success story. “They've shown how you can do this right--implementing it at a community level scale."

In this week's Friday Five, breathing this way may cut down on anxiety, a fasting regimen that could make you sick, this type of job makes men more virile, 3D printed hearts could save your life, and the role of metformin in preventing dementia.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five, featuring interviews with Dr. David Spiegel, associate chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford, and Dr. Filip Swirski, professor of medicine and cardiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five, featuring interviews with Dr. David Spiegel, associate chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford, and Dr. Filip Swirski, professor of medicine and cardiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

- Breathing this way cuts down on anxiety*

- Could your fasting regimen make you sick?

- This type of job makes men more virile

- 3D printed hearts could save your life

- Yet another potential benefit of metformin

* This video with Dr. Andrew Huberman of Stanford shows exactly how to do the breathing practice.

This podcast originally aired on March 3, 2023.