Edible water bubble pods, called Ooho, made by Skipping Rock Labs. (Photo credit: Instagram account of Ooho water)

Here's something to chew on. Can a gulp of water help save the planet? If you're drinking *and* eating your water at the same time, the answer may be yes.

The tasteless packaging is made from brown seaweed that biodegrades naturally in four to six weeks.

The Lowdown

A start-up company called Skipping Rocks Lab has created a "water bubble" encased in an edible sachet that you can pop in your mouth whole. Or if you're not into swallowing it, you can tear off the edge, drink up, and toss the rest in a composter. The tasteless packaging is made from brown seaweed that biodegrades naturally in four to six weeks, whereas plastic water bottles can linger for hundreds of years.

The founders of the London-based company are determined to "make plastic packaging disappear." They had two foodie inspirations: molecular gastronomists and fruit. They tried to emulate the way chefs used edible membranes to encase bubbles of liquid to make things like fake caviar and fake egg yolks; and they also considered the peel of an orange or banana, which protects the tasty insides but can be composted.

The sachets can also contain other liquids that come in single-serve plastic containers -- think packets of condiments with takeout meals, specialty cocktails at parties, and especially single servings of water for sporting events. The London Marathon last month gave out the water bubble pods at a station along the route, using them to replace 200,000 plastic bottles that would have likely ended up first in the street, and ultimately in the ocean.

Next Up

The engineers and chemists at Skipping Rocks intend to lease their machines to others who can then manufacture their own sachets on-site to fill with whatever they desire. The new material, which is dubbed "Notpla" (not plastic), also has other applications beyond holding liquids. It can be used to replace the plastic lining in cardboard takeout boxes, for example. And the startup is working on additional materials to replace other types of ubiquitous plastic packaging, like the netting that encases garlic and onions, and the sachets that hold nails and screws.

Edible water bubbles may be the future of drinks at sporting events and festivals.

Open Questions

One hurdle is that the pods are not very hardy, so while they work fine to hand out along a marathon route, they wouldn't really be viable for a hiker to throw in her backpack. Another issue concerns the retail market: to be stable on a shelf, they'd have to be protected from all that handling, which brings us back to the problem the engineers tried to solve in the first place -- disposable packaging.

So while Skipping Rocks may not achieve their ultimate goal of ridding the world of plastic waste, a little progress can still go a long way. If edible water bubbles are the future of drinks at sporting events and festivals, the environment will certainly benefit from their presence -- and absence.

Wild-Caught Seafood Has Been Notoriously Shady – Until Now

The Dock to Dish model has expanded across North and Central America. Above, artisanal fishermen on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica head out to sea seeking schools of abundant forage fish to supply the program.

In 2012, entrepreneur Sean Barrett founded Dock to Dish in Montauk, New York. It connected local fishermen and women with local chefs, enabling the chefs to serve hyper-fresh seafood – with the caveat that they didn't know what would be on their menus until it arrived in their kitchens the night before.

"Since we're not a seafood-centric culture, people don't know what's what, where fish are from, and when they're in season, making them easy to dupe."

In June of 2017, The United Nations Foundation designated Dock to Dish as one of the top breakthrough innovations that can scale to solve the ocean's grand challenges. His company has since expanded across the Americas and has just opened up shop in Fiji. Leapsmag recently chatted with Barrett about his inspirations and ideas for how to overcome the hurdles of farming wild seafood. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What inspired you to start Dock to Dish?

The short story is "A Tale of Two Hills."

The first is Quail Hill Farm in Amagansett. I grew up in the commercial fishing port of Chinicock in the 1980's and 90's, working on my family's dock from an early age and in the restaurant industry in my teens. By my thirties, I had accrued my 10,000 hours of experience in both dock and dish. I watched the food system shift from local to global, especially in seafood. By the early 2000's, over 90 percent of seafood in the U.S. was imported. It was bad.

Quail Hill was the first CSA [Community Supported Agriculture, in which customers pay up front for a share in whatever crops grow (or don't) on the farm that season] in the U.S., founded in 1990. So people in the area were accustomed to getting their produce that way. Scott Chaskey, the poet farmer at Quail Hill, really helped crystallize the philosophy for me and inspired me to apply it to seafood. Fishermen had always been bringing a share of their day's catch to their neighbors; now we were just doing it in a more formalized way.

The second is Blue Hill at Stone Barns. [Executive chef and co-owner] Dan Barber literally trademarked the phrase "Know Thy Farmer"; we just expanded it to Know Thy Fisherman and it took off like a rocket ship. His connections in the restaurant world were also indispensable.

17th generation Montauk fisherman Captain Bruce Beckwith (above left) with crew Charlie Etzel (Center) and Jeremy Gould (right).

Do you have any issues that are unique to seafood that a CSA or meat co-op wouldn't face?

This food is WILD. People are totally disconnected from what that word means, and it makes seafood different from everything else. Everything changes when viewed through the prism of that word.

This is the last wild food we eat. It is unpredictable, and subject to variables ranging from currents and tides to which way the wind is blowing. But it is what makes our model so much more impactful and beneficial than the industrialized, demand-driven marketplace that surrounds us. The ocean and its ecosystem are the boss, not chefs and consumers.

There has a been a lot of press about seafood being mislabeled. How and why does that happen? Can Dock to Dish fix it?

Imported, farmed seafood is cheap. Wild, sustainable seafood is not. People are buying low and selling high to make a buck; and while fisheries are extraordinarily regulated, the marketplace isn't. There is no punishment for mislabeling, and no means to correct it. Since we're not a seafood-centric culture, people don't know what's what, where fish are from, and when they're in season, making them easy to dupe. But technology is poised to fix that; DNA testing can test what a fish sample is and where it's from, and SciO handheld spectrometers – soon to be incorporated into smartphones – can analyze the molecular makeup of anything on your plate.

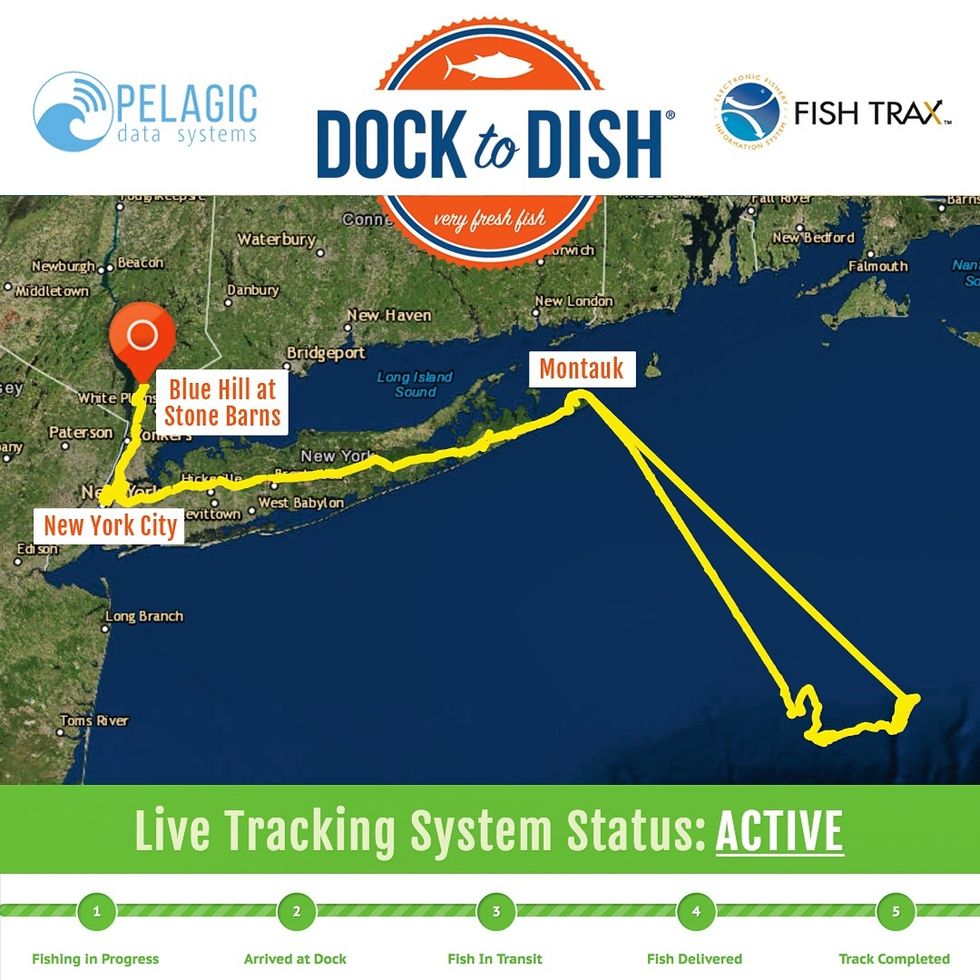

We've created the first ever live tracking system and database for wild fisheries. It is similar to the electronic system used to monitor commercial fisheries, thanks to which the resurgence of wild seafood in U.S. waters is a model for the rest of the world. We have vessel tracking devices on our fishing boats and delivery vans, so the path of each fish is publicly available in real time.

In 2017, Dock to Dish launched the world's first live "end-to-end" tracking system for wild seafood, which provides full chain transparency and next-generation traceability for members.

People are increasingly looking to seafood as a healthier, possibly more sustainable protein option than meat. Can Dock to Dish scale up to accommodate this potentially growing market?

Nope. We can't scale; the supply is finite. That's why the price keeps going up. To avoid becoming "fish for the rich" we are working closely with Greenwave.org to create a network of 3D restorative ocean farms growing kelp and shellfish, which sequester carbon and nitrogen out of the air and soil. Restorative, because sustainable is no longer an option. In fifty years, a plate of seafood will be mostly ocean vegetables with a small amount of finfish as a garnish.

Sloppy Science Happens More Than You Think

Manipulating DNA through gene editing.

The media loves to tout scientific breakthroughs, and few are as toutable – and in turn, have been as touted – as CRISPR. This method of targeted DNA excision was discovered in bacteria, which use it as an adaptive immune system to combat reinfection with a previously encountered virus.

Shouldn't the editors at a Nature journal know better than to have published an incorrect paper in the first place?

It is cool on so many levels: not only is the basic function fascinating, reminding us that we still have more to discover about even simple organisms that we thought we knew so well, but the ability it grants us to remove and replace any DNA of interest has almost limitless applications in both the lab and the clinic. As if that didn't make it sexy enough, add in a bicoastal, male-female, very public and relatively ugly patent battle, and the CRISPR story is irresistible.

And then last summer, a bombshell dropped. The prestigious journal Nature Methods published a paper in which the authors claimed that CRISPR could cause many unintended mutations, rendering it unfit for clinical use. Havoc duly ensued; stocks in CRISPR-based companies plummeted. Thankfully, the authors of the offending paper were responsible, good scientists; they reassessed, then recanted. Their attention- and headline- grabbing results were wrong, and they admitted as much, leading Nature Methods to formally retract the paper this spring.

How did this happen? Shouldn't the editors at a Nature journal know better than to have published this in the first place?

Alas, high-profile scientific journals publish misleading and downright false results fairly regularly. Some errors are unavoidable – that's how the scientific method works. Hypotheses and conclusions will invariably be overturned as new data becomes available and new technologies are developed that allow for deeper and deeper studies. That's supposed to happen. But that's not what we're talking about here. Nor are we talking about obvious offenses like outright plagiarism. We're talking about mistakes that are avoidable, and that still have serious ramifications.

The cultures of both industry and academia promote research that is poorly designed and even more poorly analyzed.

Two parties are responsible for a scientific publication, and thus two parties bear the blame when things go awry: the scientists who perform and submit the work, and the journals who publish it. Unfortunately, both are incentivized for speedy and flashy publications, and not necessarily for correct publications. It is hardly a surprise, then, that we end up with papers that are speedy and flashy – and not necessarily correct.

"Scientists don't lie and submit falsified data," said Andy Koff, a professor of Molecular Biology at Sloan Kettering Institute, the basic research arm of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Richard Harris, who wrote the book on scientific misconduct running the gamut from unconscious bias and ignorance to more malicious fraudulence, largely concurs (full disclosure: I reviewed the book here). "Scientists want to do good science and want to be recognized as such," he said. But even so, the cultures of both industry and academia promote research that is poorly designed and even more poorly analyzed. In Rigor Mortis: How Sloppy Science Creates Worthless Cures, Crushes Hope, and Wastes Millions, Harris describes how scientists must constantly publish in order to maintain their reputations and positions, to get grants and tenure and students. "They are disincentivized from doing that last extra experiment to prove their results," he said; it could prove too risky if it could cost them a publication.

Ivan Oransky and Adam Marcus founded Retraction Watch, a blog that tracks the retraction of scientific papers, in 2010. Oransky pointed out that blinded peer review – the pride and joy of the scientific publishing enterprise – is a large part of the problem. "Pre-publication peer review is still important, but we can't treat it like the only check on the system. Papers are being reviewed by non-experts, and reviewers are asked to review papers only tangentially related to their field. Moreover, most peer reviewers don't look at the underlying or raw data, even when it is available. How then can they tell if the analysis is flawed or the data is accurate?" he wondered.

Mistaken publications also erode the public's opinion of legitimate science, which is problematic since that opinion isn't especially high to begin with.

Koff agreed that anonymous peer review is valuable, but severely flawed. "Blinded review forces a collective view of importance," he said. "If an article disagrees with the reviewer's worldview, the article gets rejected or forced to adhere to that worldview – even if that means pushing the data someplace it shouldn't necessarily go." We have lost the scientific principle behind review, he thinks, which was to critically analyze a paper. But instead of challenging fundamental assumptions within a paper, reviewers now tend to just ask for more and more supplementary data. And don't get him started on editors. "Editors are supposed to arbitrate between reviewers and writers and they have completely abdicated this responsibility, at every journal. They do not judge, and that's a real failing."

Harris laments the wasted time, effort, and resources that result when erroneous ideas take hold in a field, not to mention lives lost when drug discovery is predicated on basic science findings that end up being wrong. "When no one takes the time, care, and money to reproduce things, science isn't stopping – but it is slowing down," he noted. Mistaken publications also erode the public's opinion of legitimate science, which is problematic since that opinion isn't especially high to begin with.

Scientists and publishers don't only cause the problem, though – they may also provide the solution. Both camps are increasingly recognizing and dealing with the crisis. The self-proclaimed "data thugs" Nick Brown and James Heathers use pretty basic arithmetic to reveal statistical errors in papers. The microbiologist Elisabeth Bik scans the scientific literature for problematic images "in her free time." The psychologist Brian Nosek founded the Center for Open Science, a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting openness, integrity, and reproducibility in scientific research. The Nature family of journals – yes, the one responsible for the latest CRISPR fiasco – has its authors complete a checklist to combat irreproducibility, à la Atul Gawande. And Nature Communications, among other journals, uses transparent peer review, in which authors can opt to have the reviews of their manuscript published anonymously alongside the completed paper. This practice "shows people how the paper evolved," said Koff "and keeps the reviewer and editor accountable. Did the reviewer identify the major problems with the paper? Because there are always major problems with a paper."