Sustainable Urban Farming Has a Rising Hot Star: Bugs

The larvae of adult black soldier flies can turn food waste into sustainable protein with minimal methane gas emissions.

In Sydney, Australia, in the basement of an inner-city high-rise, lives a mass of unexpected inhabitants: millions of maggots. The insects are far from unwelcome. They are there to feast on the food waste generated by the building's human residents.

Goterra, the start-up that installed the maggots in the building in December, belongs to the rapidly expanding insect agriculture industry, which is experiencing a surge of investment worldwide.

The maggots – the larvae of the black soldier fly – are voracious, unfussy eaters. As adult flies, they don't eat, so the young fatten up swiftly on whatever they can get. Goterra's basement colony can munch through 5 metric tons of waste in a day.

"Maggots are nature's cleaners," says Bob Gordon, Head of Growth at Goterra. "They're a great tool to manage waste streams."

Their capacity to consume presents a neat response to the problem of food waste, which contributes up to 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions each year as it rots in landfill.

"The maggots eat the food fairly fresh," Gordon says. "So, there's minimal degradation and you don't get those methane emissions."

Alongside their ability to devour waste, the soldier fly larvae hold further agricultural promise: they yield an incredibly efficient protein. After the maggots have binged for about 12 days, Goterra harvests and processes them into a protein-rich livestock feed. Their excrement, known as frass, is also collected and turned into soil conditioner.

"We are producing protein in a basement," says Gordon. "It's urban farming – really sustainable, urban farming."

Goterra's module in the basement at Barangaroo, Sydney.

Supplied by Goterra

Goterra's founder Olympia Yarger started producing the insects in "buckets in her backyard" in 2016. Today, Goterra has a large-scale processing plant and has developed proprietary modules – in shipping containers – that use robotics to manage the larvae.

The modules have been installed on site at municipal buildings, hospitals, supermarkets, several McDonald's restaurants, and a range of smaller enterprises in Australia. Users pay a subscription fee and simply pour in the waste; Goterra visits once a fortnight to harvest the bugs.

Insect agriculture is well established outside of the West, and the practice is gaining traction around the world. China has mega-facilities that can process hundreds of tons of waste in a day. In Kenya, a program recently trained 2000 farmers in soldier fly farming to boost their economic security. French biotech company InnovaFeed, in partnership with US agricultural heavyweight ADM, plans to build "the world's largest insect protein facility" in Illinois this year.

"The [maggots] are science fiction on earth. Watching them work is awe-inspiring."

But the concept is still not to everyone's taste.

"This is still a topic that I say is a bit like black liquorice – people tend to either really like it or really don't," says Wendy Lu McGill, Communications Director at the North American Coalition of Insect Agriculture (NACIA).

Formed in 2016, NACIA now has over 100 members – including researchers and commercial producers of black soldier flies, meal worms and crickets.

McGill says there have been a few iterations of insect agriculture in the US – beginning with worms produced for bait after World War II then shifting to food for exotic pets. The current focus – "insects as food and feed" – took root about a decade ago, with the establishment of the first commercial farms for this purpose.

"We're starting to see more expansion in the U.S. and a lot of the larger investments have been for black soldier fly producers," McGill says. "They tend to have larger facilities and the animal feed market they're looking at is potentially quite large."

InnovaFeed's Illinois facility is set to produce 60,000 metric tons of animal feed protein per year.

"They'll be trying to employ many different circular principles," McGill says of the project. "For example, the heat from the feed factory – the excess heat that would normally just be vented – will be used to heat the other side that's raising the black soldier fly."

Although commercial applications have started to flourish recently, scientific knowledge of the black soldier fly's potential has existed for decades.

Dr. Jeffery Tomberlin, an entomologist at Texas A&M University, has been studying the insect for over 20 years, contributing to key technologies used in the industry. He also founded Evo, a black soldier fly company in Texas, which feeds its larvae the waste from a local bakery and distillery.

"They are science fiction on earth," he says of the maggots. "Watching them work is awe-inspiring."

Tomberlin says fly farms can work effectively at different scales, and present possibilities for non-Western countries to shift towards "commodity independence."

"You don't have to have millions of dollars invested to be successful in producing this insect," he says. "[A farm] can be as simple as an open barn along the equator to a 30,000 square-foot indoor facility in the Netherlands."

As the world's population balloons, food insecurity is an increasing concern. By 2050, the UN predicts that to feed our projected population we will need to ramp up food production by at least 60%. Insect agriculture, which uses very little land and water compared to traditional livestock farming, could play a key role.

Insects may become more common human food, but the current commercial focus is animal feed. Aquaculture is a key market, with insects presenting an alternative to fish meal derived from over-exploited stocks. Insect meal is also increasingly popular in pet food, particularly in Europe.

While recent investment has been strong – NACIA says 2020 was the best year yet – reaching a scale that can match existing agricultural industries and providing a competitive price point are still hurdles for insect agriculture.

But COVID-19 has strengthened the argument for new agricultural approaches, such as the decentralized, indoor systems and circular principles employed by insect farms.

"This has given the world a preview – which no one wanted – of [future] supply chain disruptions," says McGill.

As the industry works to meet demand, Tomberlin predicts diversification and product innovation: "I think food science is going to play a big part in that. They can take an insect and create ice cream." (Dried soldier fly larvae "taste kind of like popcorn," if you were wondering.)

Tomberlin says the insects could even become an interplanetary protein source: "I do believe in that. I mean, if we're going to colonize other planets, we need to be sustainable."

But he issues a word of caution about the industry growing too big, too fast: "I think we as an industry need to be very careful of how we harness and apply [our knowledge]. The black soldier fly is considered the crown jewel today, but if it's mismanaged, it can be relegated back to a past."

Goterra's Gordon also warns against rushing into mass production: "If you're just replacing big intensive animal agriculture with big intensive animal agriculture with more efficient animals, then what's the change you're really effecting?"

But he expects the industry will continue its rise though the next decade, and Goterra – fuelled by recent $8 million Series A funding – plans to expand internationally this year.

"Within 10 years' time, I would like to see the vast majority of our unavoidable food waste being used to produce maggots to go into a protein application," Gordon says.

"There's no lack of demand. And there's no lack of food waste."

How Excessive Regulation Helped Ignite COVID-19's Rampant Spread

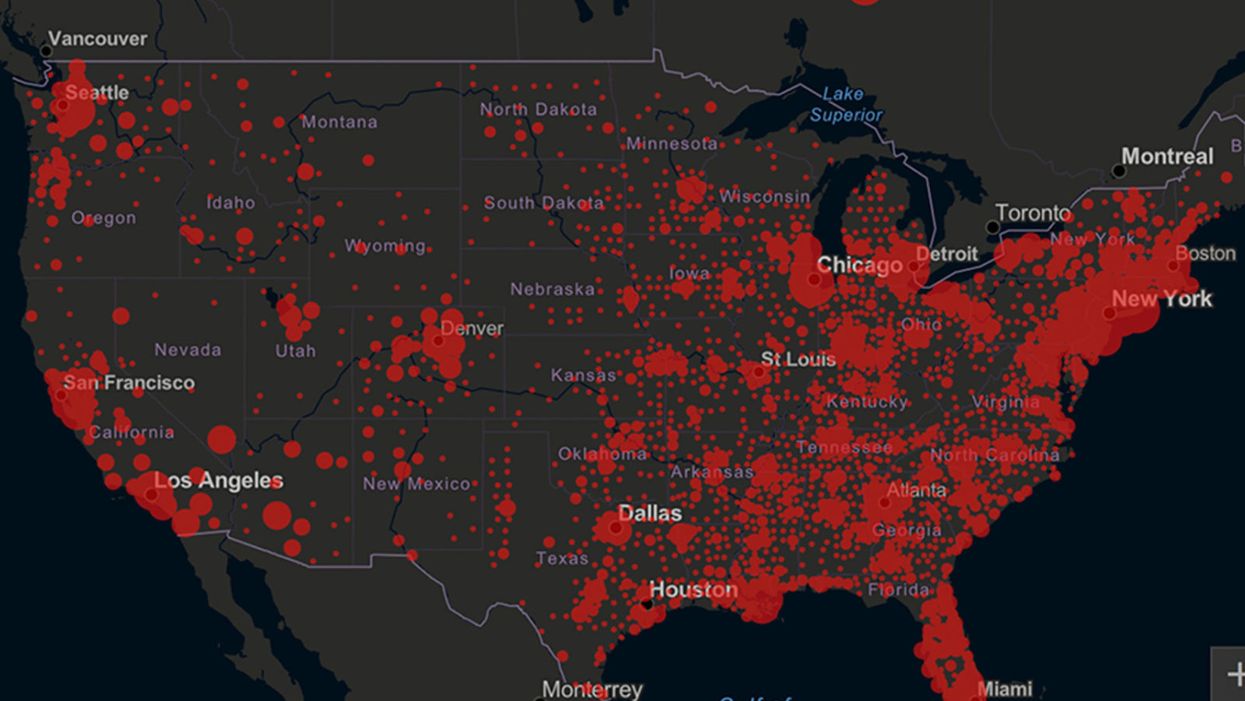

Screenshot of an interactive map of coronavirus cases across the United States, current as of 1:45 p.m. Pacific time on Tuesday, March 31st. Full map accessible at https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

When historians of the future look back at the 2020 pandemic, the heroic work of Helen Y. Chu, a flu researcher at the University of Washington, will be worthy of recognition.

Chu's team bravely defied the order and conducted the testing anyway.

In late January, Chu was testing nasal swabs for the Seattle Flu Study to monitor influenza spread when she learned of the first case of COVID-19 in Washington state. She deemed it a pressing public health matter to document if and how the illness was spreading locally, so that early containment efforts could succeed. So she sought regulatory approval to adapt the Flu Study to test for the coronavirus, but the federal government denied the request because the original project was funded to study only influenza.

Aware of the urgency, Chu's team bravely defied the order and conducted the testing anyway. Soon they identified a local case in a teenager without any travel history, followed by others. Still, the government tried to shutter their efforts until the outbreak grew dangerous enough to command attention.

Needless testing delays, prompted by excessive regulatory interference, eliminated any chances of curbing the pandemic at its initial stages. Even after Chu went out on a limb to sound alarms, a heavy-handed bureaucracy crushed the nation's ability to roll out early and widespread testing across the country. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention infamously blundered its own test, while also impeding state and private labs from coming on board, fueling a massive shortage.

The long holdup created "a backlog of testing that needed to be done," says Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease specialist who is a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security.

In a public health crisis, "the ideal situation" would allow the government's test to be "supplanted by private laboratories" without such "a lag in that transition," Adalja says. Only after the eventual release of CDC's test could private industry "begin in earnest" to develop its own versions under the Food and Drug Administration's emergency use authorization.

In a statement, CDC acknowledged that "this process has not gone as smoothly as we would have liked, but there is currently no backlog for testing at CDC."

Now, universities and corporations are in a race against time, playing catch up as the virus continues its relentless spread, also afflicting many health care workers on the front lines.

"Home-testing accessibility is key to preventing further spread of the COVID-19 pandemic."

Hospitals are attempting to add the novel coronavirus to the testing panel of their existent diagnostic machines, which would reduce the results processing time from 48 hours to as little as four hours. Meanwhile, at least four companies announced plans to deliver at-home collection tests to help meet the demand – before a startling injunction by the FDA halted their plans.

Everlywell, an Austin, Texas-based digital health company, had been set to launch online sales of at-home collection kits directly to consumers last week. Scaling up in a matter of days to an initial supply of 30,000 tests, Everlywell collaborated with multiple laboratories where consumers could ship their nasal swab samples overnight, projecting capacity to screen a quarter-million individuals on a weekly basis, says Frank Ong, chief medical and scientific officer.

Secure digital results would have been available online within 48 hours of a sample's arrival at the lab, as well as a telehealth consultation with an independent, board-certified doctor if someone tested positive, for an inclusive $135 cost. The test has a less than 3 percent false-negative rate, Ong says, and in the event of an inadequate self-swab, the lab would not report a conclusive finding. "Home-testing accessibility," he says, "is key to preventing further spread of the COVID-19 pandemic."

But on March 20, the FDA announced restrictions on home collection tests due to concerns about accuracy. The agency did note "the public health value in expanding the availability of COVID-19 testing through safe and accurate tests that may include home collection," while adding that "we are actively working with test developers in this space."

After the restrictions were announced, Everlywell decided to allocate its initial supply of COVID-19 collection kits to hospitals, clinics, nursing homes, and other qualifying health care companies that can commit to no-cost screening of frontline workers and high-risk symptomatic patients. For now, no consumers can order a home-collection test.

"Losing two months is close to disastrous, and that's what we did."

Currently, the U.S. has ramped up to testing an estimated 100,000 people a day, according to Stat News. But 150,000 or more Americans should be tested every day, says Ashish Jha, professor and director of the Harvard Global Health Institute. Due to the dearth of tests, many sick people who suspect they are infected still cannot get confirmation unless they need to be hospitalized.

To give a concrete sense of how far behind we are in testing, consider Palm Beach County, Fla. The state's only drive-thru test center just opened there, requiring an appointment. The center aims to test 750 people per day, but more than 330,000 people have already called to try to book a slot.

"This is such a rapidly moving infection that losing a few days is bad, and losing a couple of weeks is terrible," says Jha, a practicing general internist. "Losing two months is close to disastrous, and that's what we did."

At this point, it will take a long time to fully ramp up. "We are blindfolded," he adds, "and I'd like to take the blindfolds off so we can fight this battle with our eyes wide open."

Better late than never: Yesterday, FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn said in a statement that the agency has worked with more than 230 test developers and has approved 20 tests since January. An especially notable one was authorized last Friday – 67 days since the country's first known case in Washington state. It's a rapid point-of-care test from medical-device firm Abbott that provides positive results in five minutes and negative results in 13 minutes. Abbott will send 50,000 tests a day to urgent care settings. The first tests are expected to ship tomorrow.

Your Privacy vs. the Public's Health: High-Tech Tracking to Fight COVID-19 Evokes Orwell

Governments around the world are using technology to track their citizens to contain COVID-19.

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed public health and personal privacy on a collision course, as smartphone technology has completely rewritten the book on contact tracing.

It's not surprising that an autocratic regime like China would adopt such measures, but democracies such as Israel have taken a similar path.

The gold standard – patient interviews and detective work – had been in place for more than a century. It's been all but replaced by GPS data in smartphones, which allows contact tracing to occur not only virtually in real time, but with vastly more precision.

China has gone the furthest in using such tech to monitor and prevent the spread of the coronavirus. It developed an app called Health Code to determine which of its citizens are infected or at risk of becoming infected. It has assigned each individual a color code – red, yellow or green – and restricts their movement depending on their assignment. It has also leveraged its millions of public video cameras in conjunction with facial recognition tech to identify people in public who are not wearing masks.

It's not surprising that an autocratic regime like China would adopt such measures, but democracies such as Israel have taken a similar path. The national security agency Shin Bet this week began analyzing all personal cellphone data under emergency measures approved by the government. It texts individuals when it's determined they had been in contact with someone who had the coronavirus. In Spain and China, police have sent drones aloft searching for people violating stay-at-home orders. Commands to disperse can be issued through audio systems built into the aircraft. In the U.S., efforts are underway to lift federal restrictions on drones so that police can use them to prevent people from gathering.

The chief executive of a drone manufacturer in the U.S. aptly summed up the situation in an interview with the Financial Times: "It seems a little Orwellian, but this could save lives."

Epidemics and how they're surveilled often pose thorny dilemmas, according to Craig Klugman, a bioethicist and professor of health sciences at DePaul University in Chicago. "There's always a moral issue to contact tracing," he said, adding that the issue doesn't change by nation, only in the way it's resolved.

"Once certain privacy barriers have been breached, it can be difficult to roll them back again."

In China, there's little to no expectation for privacy, so their decision to take the most extreme measures makes sense to Klugman. "In China, the community comes first. In the U.S., individual rights come first," he said.

As the U.S. has scrambled to develop testing kits and manufacture ventilators to identify potential patients and treat them, individual rights have mostly not received any scrutiny. However, that could change in the coming weeks.

The American approach is also leaning toward using smartphone apps, but in a way that may preserve the privacy of users. Researchers at MIT have released a prototype known as Private Kit: Safe Paths. Patients diagnosed with the coronavirus can use the app to disclose their location trail for the prior 28 days to other users without releasing their specific identity. They also have the option of sharing the data with public health officials. But such an app would only be effective if there is a significant number of users.

Singapore is offering a similar app to its citizens known as TraceTogether, which uses both GPS and Bluetooth pings among users to trace potential encounters. It's being offered on a voluntary basis.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation, the leading nonprofit organization defending civil liberties in the digital world, said it is monitoring how these apps are developed and deployed. "Governments around the world are demanding new dragnet location surveillance powers to contain the COVID-19 outbreak," it said in a statement. "But before the public allows their governments to implement such systems, governments must explain to the public how these systems would be effective in stopping the spread of COVID-19. There's no questioning the need for far-reaching public health measures to meet this urgent challenge, but those measures must be scientifically rigorous, and based on the expertise of public health professionals."

Andrew Geronimo, director of the intellectual property venture clinic at the Case Western University School of Law, said that the U.S. government is currently in talks with Facebook, Google and other tech companies about using deidentified location data from smartphones to better monitor the progress of the outbreak. He was hesitant to endorse such a step.

"These companies may say that all of this data is anonymized," he said, "but studies have shown that it is difficult to fully anonymize data sets that contain so much information about us."

Beyond the technical issues, social attitudes may mount another challenge. Epic events such as 9/11 tend to loosen vigilance toward protecting privacy, according to Klugman and Geronimo. And as more people are sickened and hospitalized in the U.S. with COVID-19, Klugman believes more Americans will be willing to allow themselves to be tracked. "If that happens, there needs to be a time limitation," he said.

However, even if time limits are put in place, Geronimo believes it would lead to an even greater rollback of privacy during the next crisis.

"Once certain privacy barriers have been breached, it can be difficult to roll them back again," he warned. "And the prior incidents could always be used as a precedent – or as proof of concept."