“Virtual Biopsies” May Soon Make Some Invasive Tests Unnecessary

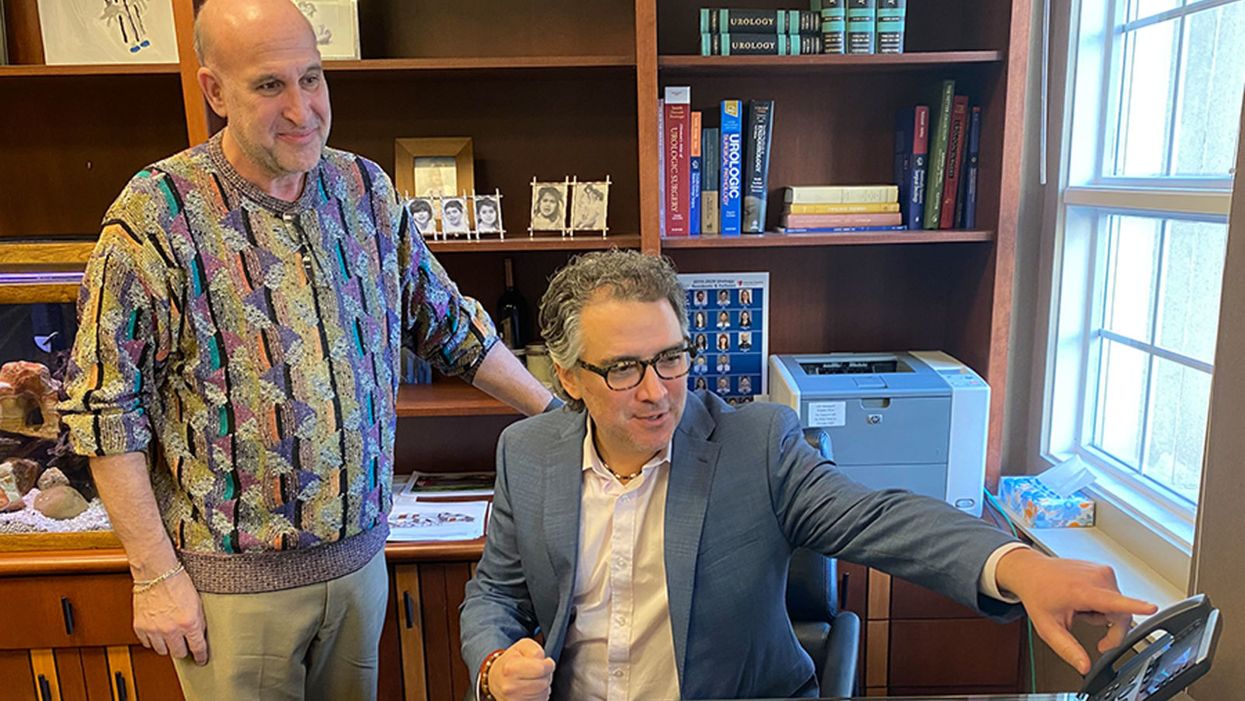

Patient Dan Chessin met recently in Dr. Lee Ponsky's office at University Hospitals, discussing Chessin's history with prostate cancer.

At his son's college graduation in 2017, Dan Chessin felt "terribly uncomfortable" sitting in the stadium. The bouts of pain persisted, and after months of monitoring, a urologist took biopsies of suspicious areas in his prostate.

This innovation may enhance diagnostic precision and promptness, but it also brings ethical concerns to the forefront.

"In my case, the biopsies came out cancerous," says Chessin, 60, who underwent robotic surgery for intermediate-grade prostate cancer at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.

Although he needed a biopsy, as most patients today do, advances in radiologic technology may make such invasive measures unnecessary in the future. Researchers are developing better imaging techniques and algorithms—a form of computer science called artificial intelligence, in which machines learn and execute tasks that typically require human brain power.

This innovation may enhance diagnostic precision and promptness. But it also brings ethical concerns to the forefront of the conversation, highlighting the potential for invasion of privacy, unequal patient access, and less physician involvement in patient care.

A National Academy of Medicine Special Publication, released in December, emphasizes that setting industry-wide standards for use in patient care is essential to AI's responsible and transparent implementation as the industry grapples with voluminous quantities of data. The technology should be viewed as a tool to supplement decision-making by highly trained professionals, not to replace it.

MRI--a test that uses powerful magnets, radio waves, and a computer to take detailed images inside the body--has become highly accurate in detecting aggressive prostate cancer, but its reliability is more limited in identifying low and intermediate grades of malignancy. That's why Chessin opted to have his prostate removed rather than take the chance of missing anything more suspicious that could develop.

His urologist, Lee Ponsky, says AI's most significant impact is yet to come. He hopes University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center's collaboration with research scientists at its academic affiliate, Case Western Reserve University, will lead to the invention of a virtual biopsy.

A National Cancer Institute five-year grant is funding the project, launched in 2017, to develop a combined MRI and computerized tool to support more accurate detection and grading of prostate cancer. Such a tool would be "the closest to a crystal ball that we can get," says Ponsky, professor and chairman of the Urology Institute.

In situations where AI has guided diagnostics, radiologists' interpretations of breast, lung, and prostate lesions have improved as much as 25 percent, says Anant Madabhushi, a biomedical engineer and director of the Center for Computational Imaging and Personalized Diagnostics at Case Western Reserve, who is collaborating with Ponsky. "AI is very nascent," Madabhushi says, estimating that fewer than 10 percent of niche academic medical centers have used it. "We are still optimizing and validating the AI and virtual biopsy technology."

In October, several North American and European professional organizations of radiologists, imaging informaticists, and medical physicists released a joint statement on the ethics of AI. "Ultimate responsibility and accountability for AI remains with its human designers and operators for the foreseeable future," reads the statement, published in the Journal of the American College of Radiology. "The radiology community should start now to develop codes of ethics and practice for AI that promote any use that helps patients and the common good and should block use of radiology data and algorithms for financial gain without those two attributes."

Overreliance on new technology also poses concern when humans "outsource the process to a machine."

The statement's leader author, radiologist J. Raymond Geis, says "there's no question" that machines equipped with artificial intelligence "can extract more information than two human eyes" by spotting very subtle patterns in pixels. Yet, such nuances are "only part of the bigger picture of taking care of a patient," says Geis, a senior scientist with the American College of Radiology's Data Science Institute. "We have to be able to combine that with knowledge of what those pixels mean."

Setting ethical standards is high on all physicians' radar because the intricacies of each patient's medical record are factored into the computer's algorithm, which, in turn, may be used to help interpret other patients' scans, says radiologist Frank Rybicki, vice chair of operations and quality at the University of Cincinnati's department of radiology. Although obtaining patients' informed consent in writing is currently necessary, ethical dilemmas arise if and when patients have a change of heart about the use of their private health information. It is likely that removing individual data may be possible for some algorithms but not others, Rybicki says.

The information is de-identified to protect patient privacy. Using it to advance research is akin to analyzing human tissue removed in surgical procedures with the goal of discovering new medicines to fight disease, says Maryellen Giger, a University of Chicago medical physicist who studies computer-aided diagnosis in cancers of the breast, lung, and prostate, as well as bone diseases. Physicians who become adept at using AI to augment their interpretation of imaging will be ahead of the curve, she says.

As with other new discoveries, patient access and equality come into play. While AI appears to "have potential to improve over human performance in certain contexts," an algorithm's design may result in greater accuracy for certain groups of patients, says Lucia M. Rafanelli, a political theorist at The George Washington University. This "could have a disproportionately bad impact on one segment of the population."

Overreliance on new technology also poses concern when humans "outsource the process to a machine." Over time, they may cease developing and refining the skills they used before the invention became available, said Chloe Bakalar, a visiting research collaborator at Princeton University's Center for Information Technology Policy.

"AI is a paradigm shift with magic power and great potential."

Striking the right balance in the rollout of the technology is key. Rushing to integrate AI in clinical practice may cause harm, whereas holding back too long could undermine its ability to be helpful. Proper governance becomes paramount. "AI is a paradigm shift with magic power and great potential," says Ge Wang, a biomedical imaging professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York. "It is only ethical to develop it proactively, validate it rigorously, regulate it systematically, and optimize it as time goes by in a healthy ecosystem."

Fast for Longevity, with Less Hunger, with Dr. Valter Longo

Valter Longo, a biogerontologist at USC, and centenarian Rocco Longo (no relation) appear together in Italy in 2021. The elder Longo is from a part of Italy where people have fasted regularly and are enjoying long lifespans.

You’ve probably heard about intermittent fasting, where you don’t eat for about 16 hours each day and limit the window where you’re taking in food to the remaining eight hours.

But there’s another type of fasting, called a fasting-mimicking diet, with studies pointing to important benefits. For today’s podcast episode, I chatted with Dr. Valter Longo, a biogerontologist at the University of Southern California, about all kinds of fasting, and particularly the fasting-mimicking diet, which minimizes hunger as much as possible. Going without food for a period of time is an example of good stress: challenges that work at the cellular level to boost health and longevity.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

If you’ve ever spent more than a few minutes looking into fasting, you’ve almost certainly come upon Dr. Longo's name. He is the author of the bestselling book, The Longevity Diet, and the best known researcher of fasting-mimicking diets.

With intermittent fasting, your body might begin to switch up its fuel type. It's usually running on carbs you get from food, which gets turned into glucose, but without food, your liver starts making something called ketones, which are molecules that may benefit the body in a number of ways.

With the fasting-mimicking diet, you go for several days eating only types of food that, in a way, keep themselves secret from your body. So at the level of your cells, the body still thinks that it’s fasting. This is the best of both worlds – you’re not completely starving because you do take in some food, and you’re getting the boosts to health that come with letting a fast run longer than intermittent fasting. In this episode, Dr. Longo talks about the growing number of studies showing why this could be very advantageous for health, as long as you undertake the diet no more than a few times per year.

Dr. Longo is the director of the Longevity Institute at USC’s Leonard Davis School of Gerontology, and the director of the Longevity and Cancer program at the IFOM Institute of Molecular Oncology in Milan. In addition, he's the founder and president of the Create Cures Foundation in L.A., which focuses on nutrition for the prevention and treatment of major chronic illnesses. In 2016, he received the Glenn Award for Research on Aging for the discovery of genes and dietary interventions that regulate aging and prevent diseases. Dr. Longo received his PhD in biochemistry from UCLA and completed his postdoc in the neurobiology of aging and Alzheimer’s at USC.

Show links:

Create Cures Foundation, founded by Dr. Longo: www.createcures.org

Dr. Longo's Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profvalterlongo/

Dr. Longo's Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/prof_valterlongo/

Dr. Longo's book: The Longevity Diet

The USC Longevity Institute: https://gero.usc.edu/longevity-institute/

Dr. Longo's research on nutrition, longevity and disease: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35487190/

Dr. Longo's research on fasting mimicking diet and cancer: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34707136/

Full list of Dr. Longo's studies: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=Longo%2C+Valter%5BAuthor%5D&sort=date

Research on MCT oil and Alzheimer's: https://alz-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/f...

Keto Mojo device for measuring ketones

Silkworms with spider DNA spin silk stronger than Kevlar

Silkworm silk is fragile, which limits its uses, but a few extra genes can help.

Story by Freethink

The study and copying of nature’s models, systems, or elements to address complex human challenges is known as “biomimetics.” Five hundred years ago, an elderly Italian polymath spent months looking at the soaring flight of birds. The result was Leonardo da Vinci’s biomimetic Codex on the Flight of Birds, one of the foundational texts in the science of aerodynamics. It’s the science that elevated the Wright Brothers and has yet to peak.

Today, biomimetics is everywhere. Shark-inspired swimming trunks, gecko-inspired adhesives, and lotus-inspired water-repellents are all taken from observing the natural world. After millions of years of evolution, nature has quite a few tricks up its sleeve. They are tricks we can learn from. And now, thanks to some spider DNA and clever genetic engineering, we have another one to add to the list.

The elusive spider silk

We’ve known for a long time that spider silk is remarkable, in ways that synthetic fibers can’t emulate. Nylon is incredibly strong (it can support a lot of force), and Kevlar is incredibly tough (it can absorb a lot of force). But neither is both strong and tough. In all artificial polymeric fibers, strength and toughness are mutually exclusive, and so we pick the material best for the job and make do.

Spider silk, a natural polymeric fiber, breaks this rule. It is somehow both strong and tough. No surprise, then, that spider silk is a source of much study.The problem, though, is that spiders are incredibly hard to cultivate — let alone farm. If you put them together, they will attack and kill each other until only one or a few survive. If you put 100 spiders in an enclosed space, they will go about an aggressive, arachnocidal Hunger Games. You need to give each its own space and boundaries, and a spider hotel is hard and costly. Silkworms, on the other hand, are peaceful and productive. They’ll hang around all day to make the silk that has been used in textiles for centuries. But silkworm silk is fragile. It has very limited use.

The elusive – and lucrative – trick, then, would be to genetically engineer a silkworm to produce spider-quality silk. So far, efforts have been fruitless. That is, until now.

We can have silkworms creating silk six times as tough as Kevlar and ten times as strong as nylon.

Spider-silkworms

Junpeng Mi and his colleagues working at Donghua University, China, used CRISPR gene-editing technology to recode the silk-creating properties of a silkworm. First, they took genes from Araneus ventricosus, an East Asian orb-weaving spider known for its strong silk. Then they placed these complex genes – genes that involve more than 100 amino acids – into silkworm egg cells. (This description fails to capture how time-consuming, technical, and laborious this was; it’s a procedure that requires hundreds of thousands of microinjections.)

This had all been done before, and this had failed before. Where Mi and his team succeeded was using a concept called “localization.” Localization involves narrowing in on a very specific location in a genome. For this experiment, the team from Donghua University developed a “minimal basic structure model” of silkworm silk, which guided the genetic modifications. They wanted to make sure they had the exactly right transgenic spider silk proteins. Mi said that combining localization with this basic structure model “represents a significant departure from previous research.” And, judging only from the results, he might be right. Their “fibers exhibited impressive tensile strength (1,299 MPa) and toughness (319 MJ/m3), surpassing Kevlar’s toughness 6-fold.”

A world of super-materials

Mi’s research represents the bursting of a barrier. It opens up hugely important avenues for future biomimetic materials. As Mi puts it, “This groundbreaking achievement effectively resolves the scientific, technical, and engineering challenges that have hindered the commercialization of spider silk, positioning it as a viable alternative to commercially synthesized fibers like nylon and contributing to the advancement of ecological civilization.”

Around 60 percent of our clothing is made from synthetic fibers like nylon, polyester, and acrylic. These plastics are useful, but often bad for the environment. They shed into our waterways and sometimes damage wildlife. The production of these fibers is a source of greenhouse gas emissions. Now, we have a “sustainable, eco-friendly high-strength and ultra-tough alternative.” We can have silkworms creating silk six times as tough as Kevlar and ten times as strong as nylon.

We shouldn’t get carried away. This isn’t going to transform the textiles industry overnight. Gene-edited silkworms are still only going to produce a comparatively small amount of silk – even if farmed in the millions. But, as Mi himself concedes, this is only the beginning. If Mi’s localization and structure-model techniques are as remarkable as they seem, then this opens up the door to a great many supermaterials.

Nature continues to inspire. We had the bird, the gecko, and the shark. Now we have the spider-silkworm. What new secrets will we unravel in the future? And in what exciting ways will it change the world?

This article originally appeared on Freethink, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.