What’s the Right Way to Regulate Gene-Edited Crops?

A cornfield in summer.

In the next few decades, humanity faces its biggest food crisis since the invention of the plow. The planet's population, currently 7.6 billion, is expected to reach 10 billion by 2050; to avoid mass famine, according to the World Resource Institute, we'll need to produce 70 percent more calories than we do today.

Imagine that a cheap, easy-to-use, and rapidly deployable technology could make crops more fertile and strengthen their resistance to threats.

Meanwhile, climate change will bring intensifying assaults by heat, drought, storms, pests, and weeds, depressing farm yields around the globe. Epidemics of plant disease—already laying waste to wheat, citrus, bananas, coffee, and cacao in many regions—will spread ever further through the vectors of modern trade and transportation.

So here's a thought experiment: Imagine that a cheap, easy-to-use, and rapidly deployable technology could make crops more fertile and strengthen their resistance to these looming threats. Imagine that it could also render them more nutritious and tastier, with longer shelf lives and less vulnerability to damage in shipping—adding enhancements to human health and enjoyment, as well as reduced food waste, to the possible benefits.

Finally, imagine that crops bred with the aid of this tool might carry dangers. Some could contain unsuspected allergens or toxins. Others might disrupt ecosystems, affecting the behavior or very survival of other species, or infecting wild relatives with their altered DNA.

Now ask yourself: If such a technology existed, should policymakers encourage its adoption, or ban it due to the risks? And if you chose the former alternative, how should crops developed by this method be regulated?

In fact, this technology does exist, though its use remains mostly experimental. It's called gene editing, and in the past five years it has emerged as a potentially revolutionary force in many areas—among them, treating cancer and genetic disorders; growing transplantable human organs in pigs; controlling malaria-spreading mosquitoes; and, yes, transforming agriculture. Several versions are currently available, the newest and nimblest of which goes by the acronym CRISPR.

Gene editing is far simpler and more efficient than older methods used to produce genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Unlike those methods, moreover, it can be used in ways that leave no foreign genes in the target organism—an advantage that proponents argue should comfort anyone leery of consuming so-called "Frankenfoods." But debate persists over what precautions must be taken before these crops come to market.

Recently, two of the world's most powerful regulatory bodies offered very different answers to that question. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) declared in March 2018 that it "does not currently regulate, or have any plans to regulate" plants that are developed through most existing methods of gene editing. The Court of Justice of the European Union (ECJ), by contrast, ruled in July that such crops should be governed by the same stringent regulations as conventional GMOs.

Some experts suggest that the broadly permissive American approach and the broadly restrictive EU policy are equally flawed.

Each announcement drew protests, for opposite reasons. Anti-GMO activists assailed the USDA's statement, arguing that all gene-edited crops should be tested and approved before marketing. "You don't know what those mutations or rearrangements might do in a plant," warned Michael Hansen, a senior scientist with the advocacy group Consumers Union. Biotech boosters griped that the ECJ's decision would stifle innovation and investment. "By any sensible standard, this judgment is illogical and absurd," wrote the British newspaper The Observer.

Yet some experts suggest that the broadly permissive American approach and the broadly restrictive EU policy are equally flawed. "What's behind these regulatory decisions is not science," says Jennifer Kuzma, co-director of the Genetic Engineering and Society Center at North Carolina State University, a former advisor to the World Economic Forum, who has researched and written extensively on governance issues in biotechnology. "It's politics, economics, and culture."

The U.S. Welcomes Gene-Edited Food

Humans have been modifying the genomes of plants and animals for 10,000 years, using selective breeding—a hit-or-miss method that can take decades or more to deliver rewards. In the mid-20th century, we learned to speed up the process by exposing organisms to radiation or mutagenic chemicals. But it wasn't until the 1980s that scientists began modifying plants by altering specific stretches of their DNA.

Today, about 90 percent of the corn, cotton and soybeans planted in the U.S. are GMOs; such crops cover nearly 4 million square miles (10 million square kilometers) of land in 29 countries. Most of these plants are transgenic, meaning they contain genes from an unrelated species—often as biologically alien as a virus or a fish. Their modifications are designed primarily to boost profit margins for mechanized agribusiness: allowing crops to withstand herbicides so that weeds can be controlled by mass spraying, for example, or to produce their own pesticides to lessen the need for chemical inputs.

In the early days, the majority of GM crops were created by extracting the gene for a desired trait from a donor organism, multiplying it, and attaching it to other snippets of DNA—usually from a microbe called an agrobacterium—that could help it infiltrate the cells of the target plant. Biotechnologists injected these particles into the target, hoping at least one would land in a place where it would perform its intended function; if not, they kept trying. The process was quicker than conventional breeding, but still complex, scattershot, and costly.

Because agrobacteria can cause plant tumors, Kuzma explains, policymakers in the U.S. decided to regulate GMO crops under an existing law, the Plant Pest Act of 1957, which addressed dangers like imported trees infested with invasive bugs. Every GMO containing the DNA of agrobacterium or another plant pest had to be tested to see whether it behaved like a pest, and undergo a lengthy approval process. By 2010, however, new methods had been developed for creating GMOs without agrobacteria; such plants could typically be marketed without pre-approval.

Soon after that, the first gene-edited crops began appearing. If old-school genetic engineering was a shotgun, techniques like TALEN and CRISPR were a scalpel—or the search-and-replace function on a computer program. With CRISPR/Cas9, for example, an enzyme that bacteria use to recognize and chop up hostile viruses is reprogrammed to find and snip out a desired bit of a plant or other organism's DNA. The enzyme can also be used to insert a substitute gene. If a DNA sequence is simply removed, or the new gene comes from a similar species, the changes in the target plant's genotype and phenotype (its general characteristics) may be no different from those that could be produced through selective breeding. If a foreign gene is added, the plant becomes a transgenic GMO.

Companies are already teeing up gene-edited products for the U.S. market, like a cooking oil and waxy corn.

This development, along with the emergence of non-agrobacterium GMOs, eventually prompted the USDA to propose a tiered regulatory system for all genetically engineered crops, beginning with an initial screening for potentially hazardous metaboloids or ecological impacts. (The screening was intended, in part, to guard against the "off-target effects"—stray mutations—that occasionally appear in gene-edited organisms.) If no red flags appeared, the crop would be approved; otherwise, it would be subject to further review, and possible regulation.

The plan was unveiled in January 2017, during the last week of the Obama presidency. Then, under the Trump administration, it was shelved. Although the USDA continues to promise a new set of regulations, the only hint of what they might contain has been Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue's statement last March that gene-edited plants would remain unregulated if they "could otherwise have been developed through traditional breeding techniques, as long as they are not plant pests or developed using plant pests."

Because transgenic plants could not be "developed through traditional breeding techniques," this statement could be taken to mean that gene editing in which foreign DNA is introduced might actually be regulated. But because the USDA regulates conventional transgenic GMOs only if they trigger the plant-pest stipulation, experts assume gene-edited crops will face similarly limited oversight.

Meanwhile, companies are already teeing up gene-edited products for the U.S. market. An herbicide-resistant oilseed rape, developed using a proprietary technique, has been available since 2016. A cooking oil made from TALEN-tweaked soybeans, designed to have a healthier fatty-acid profile, is slated for release within the next few months. A CRISPR-edited "waxy" corn, designed with a starch profile ideal for processed foods, should be ready by 2021.

In all likelihood, none of these products will have to be tested for safety.

In the E.U., Stricter Rules Apply

Now let's look at the European Union. Since the late 1990s, explains Gregory Jaffe, director of the Project on Biotechnology at the Center for Science in the Public Interest, the EU has had a "process-based trigger" for genetically engineered products: "If you use recombinant DNA, you are going to be regulated." All foods and animal feeds must be approved and labeled if they consist of or contain more than 0.9 percent GM ingredients. (In the U.S., "disclosure" of GM ingredients is mandatory, if someone asks, but labeling is not required.) The only GM crop that can be commercially grown in EU member nations is a type of insect-resistant corn, though some countries allow imports.

European scientists helped develop gene editing, and they—along with the continent's biotech entrepreneurs—have been busy developing applications for crops. But European farmers seem more divided over the technology than their American counterparts. The main French agricultural trades union, for example, supports research into non-transgenic gene editing and its exemption from GMO regulation. But it was the country's small-farmers' union, the Confédération Paysanne, along with several allied groups, that in 2015 submitted a complaint to the ECJ, asking that all plants produced via mutagenesis—including gene-editing—be regulated as GMOs.

At this point, it should be mentioned that in the past 30 years, large population studies have found no sign that consuming GM foods is harmful to human health. GMO critics can, however, point to evidence that herbicide-resistant crops have encouraged overuse of herbicides, giving rise to poison-proof "superweeds," polluting the environment with suspected carcinogens, and inadvertently killing beneficial plants. Those allegations were key to the French plaintiffs' argument that gene-edited crops might similarly do unexpected harm. (Disclosure: Leapsmag's parent company, Bayer, recently acquired Monsanto, a maker of herbicides and herbicide-resistant seeds. Also, Leaps by Bayer, an innovation initiative of Bayer and Leapsmag's direct founder, has funded a biotech startup called JoynBio that aims to reduce the amount of nitrogen fertilizer required to grow crops.)

The ruling was "scientifically nonsensical. It's because of things like this that I'll never go back to Europe."

In the end, the EU court found in the Confédération's favor on gene editing—though the court maintained the regulatory exemption for mutagenesis induced by chemicals or radiation, citing the 'long safety record' of those methods.

The ruling was "scientifically nonsensical," fumes Rodolphe Barrangou, a French food scientist who pioneered CRISPR while working for DuPont in Wisconsin and is now a professor at NC State. "It's because of things like this that I'll never go back to Europe."

Nonetheless, the decision was consistent with longstanding EU policy on crops made with recombinant DNA. Given the difficulty and expense of getting such products through the continent's regulatory system, many other European researchers may wind up following Barrangou to America.

Getting to the Root of the Cultural Divide

What explains the divergence between the American and European approaches to GMOs—and, by extension, gene-edited crops? In part, Jennifer Kuzma speculates, it's that Europeans have a different attitude toward eating. "They're generally more tied to where their food comes from, where it's produced," she notes. They may also share a mistrust of government assurances on food safety, borne of the region's Mad Cow scandals of the 1980s and '90s. In Catholic countries, consumers may have misgivings about tinkering with the machinery of life.

But the principal factor, Kuzma argues, is that European and American agriculture are structured differently. "GM's benefits have mostly been designed for large-scale industrial farming and commodity crops," she says. That kind of farming is dominant in the U.S., but not in Europe, leading to a different balance of political power. In the EU, there was less pressure on decisionmakers to approve GMOs or exempt gene-edited crops from regulation—and more pressure to adopt a GM-resistant stance.

Such dynamics may be operating in other regions as well. In China, for example, the government has long encouraged research in GMOs; a state-owned company recently acquired Syngenta, a Swiss-based multinational corporation that is a leading developer of GM and gene-edited crops. GM animal feed and cooking oil can be freely imported. Yet commercial cultivation of most GM plants remains forbidden, out of deference to popular suspicions of genetically altered food. "As a new item, society has debates and doubts on GMO techniques, which is normal," President Xi Jinping remarked in 2014. "We must be bold in studying it, [but] be cautious promoting it."

The proper balance between boldness and caution is still being worked out all over the world. Europe's process-based approach may prevent researchers from developing crops that, with a single DNA snip, could rescue millions from starvation. EU regulations will also make it harder for small entrepreneurs to challenge Big Ag with a technology that, as Barrangou puts it, "can be used affordably, quickly, scalably, by anyone, without even a graduate degree in genetics." America's product-based approach, conversely, may let crops with hidden genetic dangers escape detection. And by refusing to investigate such risks, regulators may wind up exacerbating consumers' doubts about GM and gene-edited products, rather than allaying them.

"Science...can't tell you what to regulate. That's a values-based decision."

Perhaps the solution lies in combining both approaches, and adding some flexibility and nuance to the mix. "I don't believe in regulation by the product or the process," says CSPI's Jaffe. "I think you need both." Deleting a DNA base pair to silence a gene, for example, might be less risky than inserting a foreign gene into a plant—unless the deletion enables the production of an allergen, and the transgene comes from spinach.

Kuzma calls for the creation of "cooperative governance networks" to oversee crop genome editing, similar to bodies that already help develop and enforce industry standards in fisheries, electronics, industrial cleaning products, and (not incidentally) organic agriculture. Such a network could include farmers, scientists, advocacy groups, private companies, and governmental agencies. "Safety isn't an all-or-nothing concept," Kuzma says. "Science can tell you what some of the issues are in terms of risk and benefit, but it can't tell you what to regulate. That's a values-based decision."

By drawing together a wide range of stakeholders to make such decisions, she adds, "we're more likely to anticipate future consequences, and to develop a robust approach—one that not only seems more legitimate to people, but is actually just plain old better."

Nobel Prize goes to technology for mRNA vaccines

Katalin Karikó, pictured, and Drew Weissman won the Nobel Prize for advances in mRNA research that led to the first Covid vaccines.

When Drew Weissman received a call from Katalin Karikó in the early morning hours this past Monday, he assumed his longtime research partner was calling to share a nascent, nagging idea. Weissman, a professor of medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, and Karikó, a professor at Szeged University and an adjunct professor at UPenn, both struggle with sleep disturbances. Thus, middle-of-the-night discourses between the two, often over email, has been a staple of their friendship. But this time, Karikó had something more pressing and exciting to share: They had won the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

The work for which they garnered the illustrious award and its accompanying $1,000,000 cash windfall was completed about two decades ago, wrought through long hours in the lab over many arduous years. But humanity collectively benefited from its life-saving outcome three years ago, when both Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech’s mRNA vaccines against COVID were found to be safe and highly effective at preventing severe disease. Billions of doses have since been given out to protect humans from the upstart viral scourge.

“I thought of going somewhere else, or doing something else,” said Katalin Karikó. “I also thought maybe I’m not good enough, not smart enough. I tried to imagine: Everything is here, and I just have to do better experiments.”

Unlocking the power of mRNA

Weissman and Karikó unlocked mRNA vaccines for the world back in the early 2000s when they made a key breakthrough. Messenger RNA molecules are essentially instructions for cells’ ribosomes to make specific proteins, so in the 1980s and 1990s, researchers started wondering if sneaking mRNA into the body could trigger cells to manufacture antibodies, enzymes, or growth agents for protecting against infection, treating disease, or repairing tissues. But there was a big problem: injecting this synthetic mRNA triggered a dangerous, inflammatory immune response resulting in the mRNA’s destruction.

While most other researchers chose not to tackle this perplexing problem to instead pursue more lucrative and publishable exploits, Karikó stuck with it. The choice sent her academic career into depressing doldrums. Nobody would fund her work, publications dried up, and after six years as an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Karikó got demoted. She was going backward.

“I thought of going somewhere else, or doing something else,” Karikó told Stat in 2020. “I also thought maybe I’m not good enough, not smart enough. I tried to imagine: Everything is here, and I just have to do better experiments.”

A tale of tenacity

Collaborating with Drew Weissman, a new professor at the University of Pennsylvania, in the late 1990s helped provide Karikó with the tenacity to continue. Weissman nurtured a goal of developing a vaccine against HIV-1, and saw mRNA as a potential way to do it.

“For the 20 years that we’ve worked together before anybody knew what RNA is, or cared, it was the two of us literally side by side at a bench working together,” Weissman said in an interview with Adam Smith of the Nobel Foundation.

In 2005, the duo made their 2023 Nobel Prize-winning breakthrough, detailing it in a relatively small journal, Immunity. (Their paper was rejected by larger journals, including Science and Nature.) They figured out that chemically modifying the nucleoside bases that make up mRNA allowed the molecule to slip past the body’s immune defenses. Karikó and Weissman followed up that finding by creating mRNA that’s more efficiently translated within cells, greatly boosting protein production. In 2020, scientists at Moderna and BioNTech (where Karikó worked from 2013 to 2022) rushed to craft vaccines against COVID, putting their methods to life-saving use.

The future of vaccines

Buoyed by the resounding success of mRNA vaccines, scientists are now hurriedly researching ways to use mRNA medicine against other infectious diseases, cancer, and genetic disorders. The now ubiquitous efforts stand in stark contrast to Karikó and Weissman’s previously unheralded struggles years ago as they doggedly worked to realize a shared dream that so many others shied away from. Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman were brave enough to walk a scientific path that very well could have ended in a dead end, and for that, they absolutely deserve their 2023 Nobel Prize.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.

Scientists turn pee into power in Uganda

With conventional fuel cells as their model, researchers learned to use similar chemical reactions to make a fuel from microbes in pee.

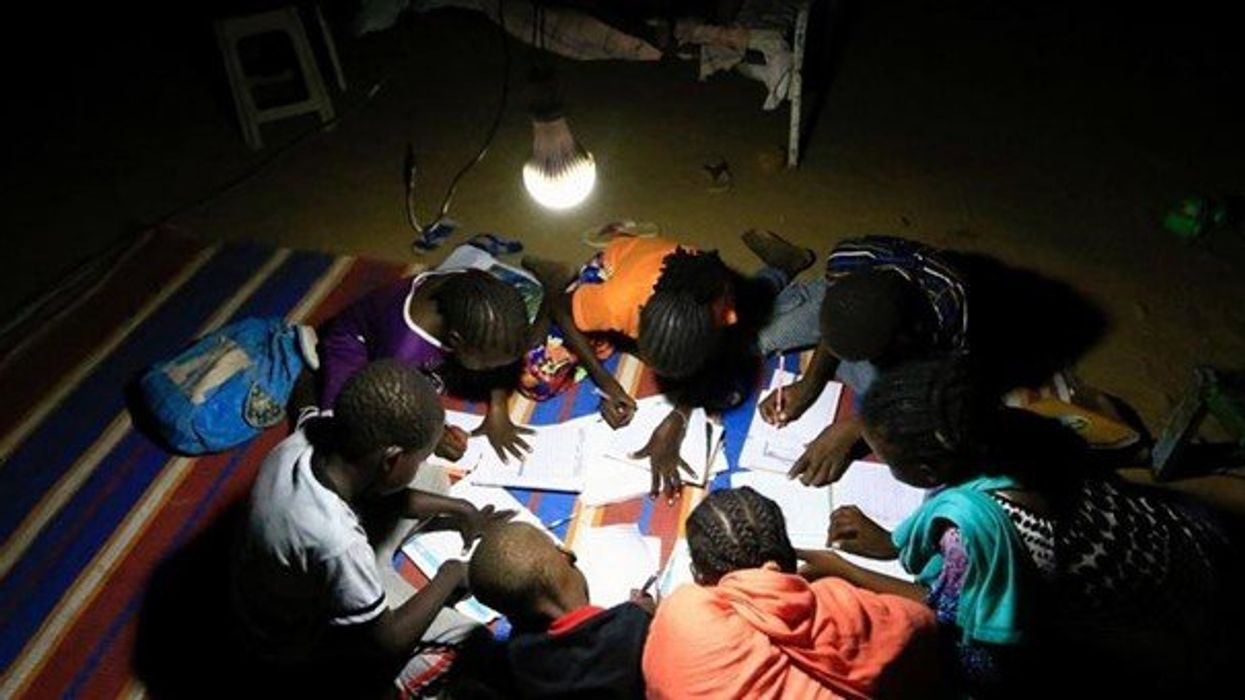

At the edge of a dirt road flanked by trees and green mountains outside the town of Kisoro, Uganda, sits the concrete building that houses Sesame Girls School, where girls aged 11 to 19 can live, learn and, at least for a while, safely use a toilet. In many developing regions, toileting at night is especially dangerous for children. Without electrical power for lighting, kids may fall into the deep pits of the latrines through broken or unsteady floorboards. Girls are sometimes assaulted by men who hide in the dark.

For the Sesame School girls, though, bright LED lights, connected to tiny gadgets, chased the fears away. They got to use new, clean toilets lit by the power of their own pee. Some girls even used the light provided by the latrines to study.

Urine, whether animal or human, is more than waste. It’s a cheap and abundant resource. Each day across the globe, 8.1 billion humans make 4 billion gallons of pee. Cows, pigs, deer, elephants and other animals add more. By spending money to get rid of it, we waste a renewable resource that can serve more than one purpose. Microorganisms that feed on nutrients in urine can be used in a microbial fuel cell that generates electricity – or "pee power," as the Sesame girls called it.

Plus, urine contains water, phosphorus, potassium and nitrogen, the key ingredients plants need to grow and survive. Human urine could replace about 25 percent of current nitrogen and phosphorous fertilizers worldwide and could save water for gardens and crops. The average U.S. resident flushes a toilet bowl containing only pee and paper about six to seven times a day, which adds up to about 3,500 gallons of water down per year. Plus cows in the U.S. produce 231 gallons of the stuff each year.

Pee power

A conventional fuel cell uses chemical reactions to produce energy, as electrons move from one electrode to another to power a lightbulb or phone. Ioannis Ieropoulos, a professor and chair of Environmental Engineering at the University of Southampton in England, realized the same type of reaction could be used to make a fuel from microbes in pee.

Bacterial species like Shewanella oneidensis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa can consume carbon and other nutrients in urine and pop out electrons as a result of their digestion. In a microbial fuel cell, one electrode is covered in microbes, immersed in urine and kept away from oxygen. Another electrode is in contact with oxygen. When the microbes feed on nutrients, they produce the electrons that flow through the circuit from one electrod to another to combine with oxygen on the other side. As long as the microbes have fresh pee to chomp on, electrons keep flowing. And after the microbes are done with the pee, it can be used as fertilizer.

These microbes are easily found in wastewater treatment plants, ponds, lakes, rivers or soil. Keeping them alive is the easy part, says Ieropoulos. Once the cells start producing stable power, his group sequences the microbes and keeps using them.

Like many promising technologies, scaling these devices for mass consumption won’t be easy, says Kevin Orner, a civil engineering professor at West Virginia University. But it’s moving in the right direction. Ieropoulos’s device has shrunk from the size of about three packs of cards to a large glue stick. It looks and works much like a AAA battery and produce about the same power. By itself, the device can barely power a light bulb, but when stacked together, they can do much more—just like photovoltaic cells in solar panels. His lab has produced 1760 fuel cells stacked together, and with manufacturing support, there’s no theoretical ceiling, he says.

Although pure urine produces the most power, Ieropoulos’s devices also work with the mixed liquids of the wastewater treatment plants, so they can be retrofit into urban wastewater utilities.

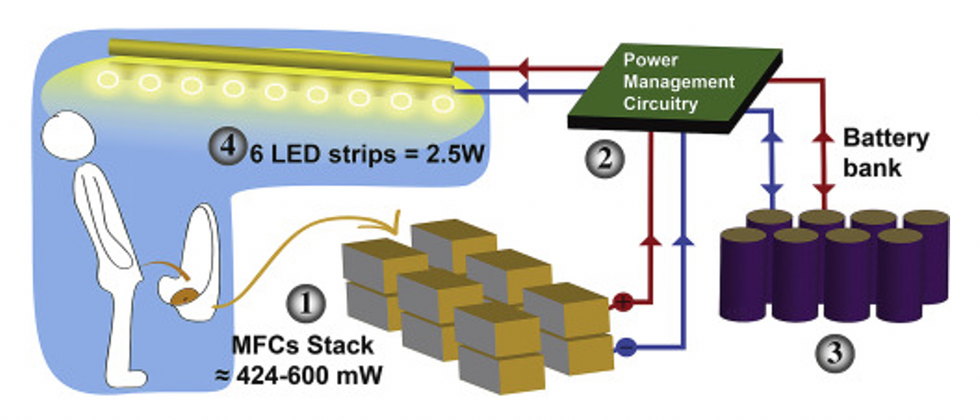

This image shows how the pee-powered system works. Pee feeds bacteria in the stack of fuel cells (1), which give off electrons (2) stored in parallel cylindrical cells (3). These cells are connected to a voltage regulator (4), which smooths out the electrical signal to ensure consistent power to the LED strips lighting the toilet.

Courtesy Ioannis Ieropoulos

Key to the long-term success of any urine reclamation effort, says Orner, is avoiding what he calls “parachute engineering”—when well-meaning scientists solve a problem with novel tech and then abandon it. “The way around that is to have either the need come from the community or to have an organization in a community that is committed to seeing a project operate and maintained,” he says.

Success with urine reclamation also depends on the economy. “If energy prices are low, it may not make sense to recover energy,” says Orner. “But right now, fertilizer prices worldwide are generally pretty high, so it may make sense to recover fertilizer and nutrients.” There are obstacles, too, such as few incentives for builders to incorporate urine recycling into new construction. And any hiccups like leaks or waste seepage will cost builders money and reputation. Right now, Orner says, the risks are just too high.

Despite the challenges, Ieropoulos envisions a future in which urine is passed through microbial fuel cells at wastewater treatment plants, retrofitted septic tanks, and building basements, and is then delivered to businesses to use as agricultural fertilizers. Although pure urine produces the most power, Ieropoulos’s devices also work with the mixed liquids of the wastewater treatment plants, so they can be retrofitted into urban wastewater utilities where they can make electricity from the effluent. And unlike solar cells, which are a common target of theft in some areas, nobody wants to steal a bunch of pee.

When Ieropoulos’s team returned to wrap up their pilot project 18 months later, the school’s director begged them to leave the fuel cells in place—because they made a major difference in students’ lives. “We replaced it with a substantial photovoltaic panel,” says Ieropoulos, They couldn’t leave the units forever, he explained, because of intellectual property reasons—their funders worried about theft of both the technology and the idea. But the photovoltaic replacement could be stolen, too, leaving the girls in the dark.

The story repeated itself at another school, in Nairobi, Kenya, as well as in an informal settlement in Durban, South Africa. Each time, Ieropoulos vowed to return. Though the pandemic has delayed his promise, he is resolute about continuing his work—it is a moral and legal obligation. “We've made a commitment to ourselves and to the pupils,” he says. “That's why we need to go back.”

Urine as fertilizer

Modern day industrial systems perpetuate the broken cycle of nutrients. When plants grow, they use up nutrients the soil. We eat the plans and excrete some of the nutrients we pass them into rivers and oceans. As a result, farmers must keep fertilizing the fields while our waste keeps fertilizing the waterways, where the algae, overfertilized with nitrogen, phosphorous and other nutrients grows out of control, sucking up oxygen that other marine species need to live. Few global communities remain untouched by the related challenges this broken chain create: insufficient clean water, food, and energy, and too much human and animal waste.

The Rich Earth Institute in Vermont runs a community-wide urine nutrient recovery program, which collects urine from homes and businesses, transports it for processing, and then supplies it as fertilizer to local farms.

One solution to this broken cycle is reclaiming urine and returning it back to the land. The Rich Earth Institute in Vermont is one of several organizations around the world working to divert and save urine for agricultural use. “The urine produced by an adult in one day contains enough fertilizer to grow all the wheat in one loaf of bread,” states their website.

Notably, while urine is not entirely sterile, it tends to harbor fewer pathogens than feces. That’s largely because urine has less organic matter and therefore less food for pathogens to feed on, but also because the urinary tract and the bladder have built-in antimicrobial defenses that kill many germs. In fact, the Rich Earth Institute says it’s safe to put your own urine onto crops grown for home consumption. Nonetheless, you’ll want to dilute it first because pee usually has too much nitrogen and can cause “fertilizer burn” if applied straight without dilution. Other projects to turn urine into fertilizer are in progress in Niger, South Africa, Kenya, Ethiopia, Sweden, Switzerland, The Netherlands, Australia, and France.

Eleven years ago, the Institute started a program that collects urine from homes and businesses, transports it for processing, and then supplies it as fertilizer to local farms. By 2021, the program included 180 donors producing over 12,000 gallons of urine each year. This urine is helping to fertilize hay fields at four partnering farms. Orner, the West Virginia professor, sees it as a success story. “They've shown how you can do this right--implementing it at a community level scale."