Which Meds are Safe When You’re Pregnant? Science Wants to Find Out

A pregnant woman is uncertain which medicine is safe to take.

Sarah Mancoll was 22 years old when she noticed a bald spot on the back of her head. A dermatologist confirmed that it was alopecia aerata, an autoimmune disorder that causes hair loss.

Of 213 new drugs approved from 2003 to 2012, only five percent included any data from pregnant women.

She successfully treated the condition with corticosteroid shots for nearly 10 years. Then Mancoll and her husband began thinking about starting a family. Would the shots be safe for her while pregnant? For the fetus? What about breastfeeding?

Mancoll consulted her primary care physician, her dermatologist, even a pediatrician. Without clinical data, no one could give her a definitive answer, so she stopped treatment to be "on the safe side." By the time her son was born, she'd lost at least half her hair. She returned to her Washington, D.C., public policy job two months later entirely bald—and without either eyebrows or eyelashes.

After having two more children in quick succession, Mancoll recently resumed the shots but didn't forget her experience. Today, she is an advocate for including more pregnant and lactating women in clinical studies so they can have more information about therapies than she did.

"I live a very privileged life, and I'll do just fine with or without hair, but it's not just about me," Mancoll said. "It's about a huge population of women who are being disenfranchised…They're invisible."

About 4 million women give birth each year in the United States, and many face medical conditions, from hypertension and diabetes to psychiatric disorders. A 2011 study showed that most women reported taking at least one medication while pregnant between 1976 and 2008. But for decades, pregnant and lactating women have been largely excluded from clinical drug studies that rigorously test medications for safety and effectiveness.

An estimated 98 percent of government-approved drug treatments between 2000 and 2010 had insufficient data to determine risk to the fetus, and close to 75 percent had no human pregnancy data at all. All told, of 213 new pharmaceuticals approved from 2003 to 2012, only five percent included any data from pregnant women.

But recent developments suggest that could be changing. Amid widespread concerns about increased maternal mortality rates, women's health advocates, physicians, and researchers are sensing and encouraging a cultural shift toward protecting women through responsible research instead of from research.

"The question is not whether to do research with pregnant women, but how," Anne Drapkin Lyerly, professor and associate director of the Center for Bioethics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, wrote last year in an op-ed. "These advances are essential. It is well past time—and it is morally imperative—for research to benefit pregnant women."

"In excluding pregnant women from drug trials to protect them from experimentation, we subject them to uncontrolled experimentation."

To that end, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Ethics acknowledged that research trials need to be better designed so they don't "inappropriately constrain the reproductive choices of study participants or unnecessarily exclude pregnant women." A federal task force also called for significantly expanded research and the removal of regulatory barriers that make it difficult for pregnant and lactating women to participate in research.

Several months ago, a government change to a regulation known as the Common Rule took effect, removing pregnant women as a "vulnerable population" in need of special protections -- a designation that had made it more difficult to enroll them in clinical drug studies. And just last week, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued new draft guidances for industry on when and how to include pregnant and lactating women in clinical trials.

Inclusion is better than the absence of data on their treatment, said Catherine Spong, former chair of the federal task force.

"It's a paradox," said Spong, professor of obstetrics and gynecology and chief of maternal fetal medicine at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. "There is a desire to protect women and fetuses from harm, which is translated to a reluctance to include them in research. By excluding them, the evidence for their care is limited."

Jacqueline Wolf, a professor of the history of medicine at Ohio University, agreed.

"In excluding pregnant women from drug trials to protect them from experimentation, we subject them to uncontrolled experimentation," she said. "We give them the medication without doing any research, and that's dangerous."

Women, of course, don't stop getting sick or having chronic medical conditions just because they are pregnant or breastfeeding, and conditions during pregnancy can affect a baby's health later in life. Evidence-based data is important for other reasons, too.

Pregnancy can dramatically change a woman's physiology, affecting how drugs act on her body and how her body acts or reacts to drugs. For instance, pregnant bodies can more quickly clear out medications such as glyburide, used during diabetes in pregnancy to stabilize high blood-sugar levels, which can be toxic to the fetus and harmful to women. That means a regular dose of the drug may not be enough to control blood sugar and prevent poor outcomes.

Pregnant patients also may be reluctant to take needed drugs for underlying conditions (and doctors may be hesitant to prescribe them), which in turn can cause more harm to the woman and fetus than had they been treated. For example, women who have severe asthma attacks while pregnant are at a higher risk of having low-birthweight babies, and pregnant women with uncontrolled diabetes in early pregnancy have more than four times the risk of birth defects.

Current clinical trials involving pregnant women are assessing treatments for obstructive sleep apnea, postpartum hemorrhage, lupus, and diabetes.

For Kate O'Brien, taking medication during her pregnancy was a matter of life and death. A freelance video producer who lives in New Jersey, O'Brien was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 2015 after she became pregnant with her second child, a boy. Even as she signed hospital consent forms, she had no idea if the treatment would harm him.

"It's a really awful experience," said O'Brien, who now is active with We are TB, an advocacy and support network. "All they had to tell me about the medication was just that women have been taking it for a really long time all over the world. That was the best they could do."

More and more doctors, researchers and women's health organizations and advocates are calling that unacceptable.

By indicating that filling current knowledge gaps is "a critical public health need," the FDA is signaling its support for advancing research with pregnant women, said Lyerly, also co-founder of the Second Wave Initiative, which promotes fair representation of the health interests of pregnant women in biomedical research and policies. "It's a very important shift."

Research with pregnant women can be done ethically, Lyerly said, whether by systematically collecting data from those already taking medications or enrolling pregnant women in studies of drugs or vaccines in development.

Current clinical trials involving pregnant women are assessing treatments for obstructive sleep apnea, postpartum hemorrhage, lupus, and diabetes. Notable trials in development target malaria and HIV prevention in pregnancy.

"It clearly is doable to do this research, and test trials are important to provide evidence for treatment," Spong said. "If we don't have that evidence, we aren't making the best educated decisions for women."

DNA- and RNA-based electronic implants may revolutionize healthcare

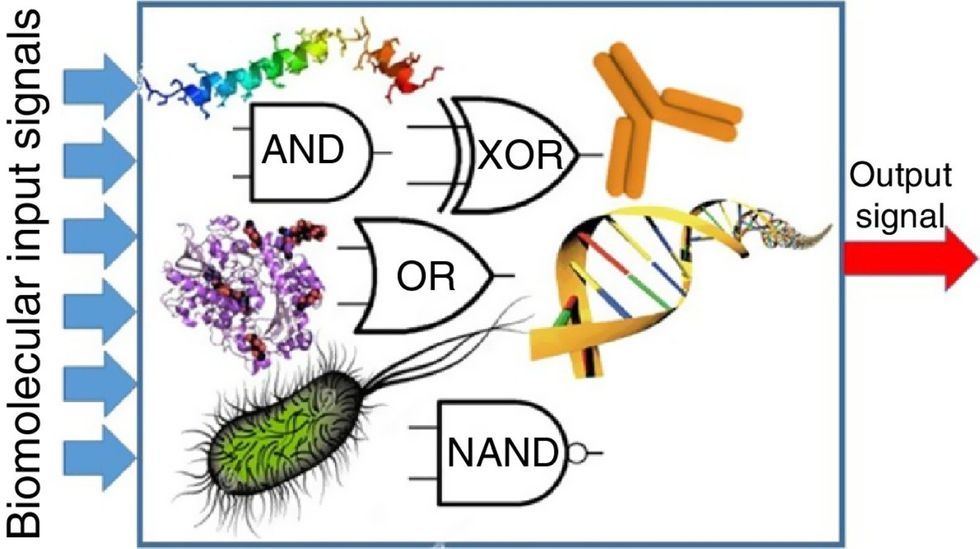

The test tubes contain tiny DNA/enzyme-based circuits, which comprise TRUMPET, a new type of electronic device, smaller than a cell.

Implantable electronic devices can significantly improve patients’ quality of life. A pacemaker can encourage the heart to beat more regularly. A neural implant, usually placed at the back of the skull, can help brain function and encourage higher neural activity. Current research on neural implants finds them helpful to patients with Parkinson’s disease, vision loss, hearing loss, and other nerve damage problems. Several of these implants, such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink, have already been approved by the FDA for human use.

Yet, pacemakers, neural implants, and other such electronic devices are not without problems. They require constant electricity, limited through batteries that need replacements. They also cause scarring. “The problem with doing this with electronics is that scar tissue forms,” explains Kate Adamala, an assistant professor of cell biology at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. “Anytime you have something hard interacting with something soft [like muscle, skin, or tissue], the soft thing will scar. That's why there are no long-term neural implants right now.” To overcome these challenges, scientists are turning to biocomputing processes that use organic materials like DNA and RNA. Other promised benefits include “diagnostics and possibly therapeutic action, operating as nanorobots in living organisms,” writes Evgeny Katz, a professor of bioelectronics at Clarkson University, in his book DNA- And RNA-Based Computing Systems.

While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output.

Adamala’s research focuses on developing such biocomputing systems using DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids. Using these molecules in the biocomputing systems allows the latter to be biocompatible with the human body, resulting in a natural healing process. In a recent Nature Communications study, Adamala and her team created a new biocomputing platform called TRUMPET (Transcriptional RNA Universal Multi-Purpose GatE PlaTform) which acts like a DNA-powered computer chip. “These biological systems can heal if you design them correctly,” adds Adamala. “So you can imagine a computer that will eventually heal itself.”

The basics of biocomputing

Biocomputing and regular computing have many similarities. Like regular computing, biocomputing works by running information through a series of gates, usually logic gates. A logic gate works as a fork in the road for an electronic circuit. The input will travel one way or another, giving two different outputs. An example logic gate is the AND gate, which has two inputs (A and B) and two different results. If both A and B are 1, the AND gate output will be 1. If only A is 1 and B is 0, the output will be 0 and vice versa. If both A and B are 0, the result will be 0. While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output. In this case, the DNA enters the logic gate as a single or double strand.

If the DNA is double-stranded, the system “digests” the DNA or destroys it, which results in non-fluorescence or “0” output. Conversely, if the DNA is single-stranded, it won’t be digested and instead will be copied by several enzymes in the biocomputing system, resulting in fluorescent RNA or a “1” output. And the output for this type of binary system can be expanded beyond fluorescence or not. For example, a “1” output might be the production of the enzyme insulin, while a “0” may be that no insulin is produced. “This kind of synergy between biology and computation is the essence of biocomputing,” says Stephanie Forrest, a professor and the director of the Biodesign Center for Biocomputing, Security and Society at Arizona State University.

Biocomputing circles are made of DNA, RNA, proteins and even bacteria.

Evgeny Katz

The TRUMPET’s promise

Depending on whether the biocomputing system is placed directly inside a cell within the human body, or run in a test-tube, different environmental factors play a role. When an output is produced inside a cell, the cell's natural processes can amplify this output (for example, a specific protein or DNA strand), creating a solid signal. However, these cells can also be very leaky. “You want the cells to do the thing you ask them to do before they finish whatever their businesses, which is to grow, replicate, metabolize,” Adamala explains. “However, often the gate may be triggered without the right inputs, creating a false positive signal. So that's why natural logic gates are often leaky." While biocomputing outside a cell in a test tube can allow for tighter control over the logic gates, the outputs or signals cannot be amplified by a cell and are less potent.

TRUMPET, which is smaller than a cell, taps into both cellular and non-cellular biocomputing benefits. “At its core, it is a nonliving logic gate system,” Adamala states, “It's a DNA-based logic gate system. But because we use enzymes, and the readout is enzymatic [where an enzyme replicates the fluorescent RNA], we end up with signal amplification." This readout means that the output from the TRUMPET system, a fluorescent RNA strand, can be replicated by nearby enzymes in the platform, making the light signal stronger. "So it combines the best of both worlds,” Adamala adds.

These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body.

The TRUMPET biocomputing process is relatively straightforward. “If the DNA [input] shows up as single-stranded, it will not be digested [by the logic gate], and you get this nice fluorescent output as the RNA is made from the single-stranded DNA, and that's a 1,” Adamala explains. "And if the DNA input is double-stranded, it gets digested by the enzymes in the logic gate, and there is no RNA created from the DNA, so there is no fluorescence, and the output is 0." On the story's leading image above, if the tube is "lit" with a purple color, that is a binary 1 signal for computing. If it's "off" it is a 0.

While still in research, TRUMPET and other biocomputing systems promise significant benefits to personalized healthcare and medicine. These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body. The study’s lead author and graduate student Judee Sharon is already beginning to research TRUMPET's ability for earlier cancer diagnoses. Because the inputs for TRUMPET are single or double-stranded DNA, any mutated or cancerous DNA could theoretically be detected from the platform through the biocomputing process. Theoretically, devices like TRUMPET could be used to detect cancer and other diseases earlier.

Adamala sees TRUMPET not only as a detection system but also as a potential cancer drug delivery system. “Ideally, you would like the drug only to turn on when it senses the presence of a cancer cell. And that's how we use the logic gates, which work in response to inputs like cancerous DNA. Then the output can be the production of a small molecule or the release of a small molecule that can then go and kill what needs killing, in this case, a cancer cell. So we would like to develop applications that use this technology to control the logic gate response of a drug’s delivery to a cell.”

Although platforms like TRUMPET are making progress, a lot more work must be done before they can be used commercially. “The process of translating mechanisms and architecture from biology to computing and vice versa is still an art rather than a science,” says Forrest. “It requires deep computer science and biology knowledge,” she adds. “Some people have compared interdisciplinary science to fusion restaurants—not all combinations are successful, but when they are, the results are remarkable.”

Crickets are low on fat, high on protein, and can be farmed sustainably. They are also crunchy.

In today’s podcast episode, Leaps.org Deputy Editor Lina Zeldovich speaks about the health and ecological benefits of farming crickets for human consumption with Bicky Nguyen, who joins Lina from Vietnam. Bicky and her business partner Nam Dang operate an insect farm named CricketOne. Motivated by the idea of sustainable and healthy protein production, they started their unconventional endeavor a few years ago, despite numerous naysayers who didn’t believe that humans would ever consider munching on bugs.

Yet, making creepy crawlers part of our diet offers many health and planetary advantages. Food production needs to match the rise in global population, estimated to reach 10 billion by 2050. One challenge is that some of our current practices are inefficient, polluting and wasteful. According to nonprofit EarthSave.org, it takes 2,500 gallons of water, 12 pounds of grain, 35 pounds of topsoil and the energy equivalent of one gallon of gasoline to produce one pound of feedlot beef, although exact statistics vary between sources.

Meanwhile, insects are easy to grow, high on protein and low on fat. When roasted with salt, they make crunchy snacks. When chopped up, they transform into delicious pâtes, says Bicky, who invents her own cricket recipes and serves them at industry and public events. Maybe that’s why some research predicts that edible insects market may grow to almost $10 billion by 2030. Tune in for a delectable chat on this alternative and sustainable protein.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Further reading:

More info on Bicky Nguyen

https://yseali.fulbright.edu.vn/en/faculty/bicky-n...

The environmental footprint of beef production

https://www.earthsave.org/environment.htm

https://www.watercalculator.org/news/articles/beef-king-big-water-footprints/

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00005/full

https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-footprint-food-methane

Insect farming as a source of sustainable protein

https://www.insectgourmet.com/insect-farming-growing-bugs-for-protein/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/insect-farming

Cricket flour is taking the world by storm

https://www.cricketflours.com/

https://talk-commerce.com/blog/what-brands-use-cricket-flour-and-why/

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.