Your Community and COVID-19: How to Make Sense of the Numbers Where You Live

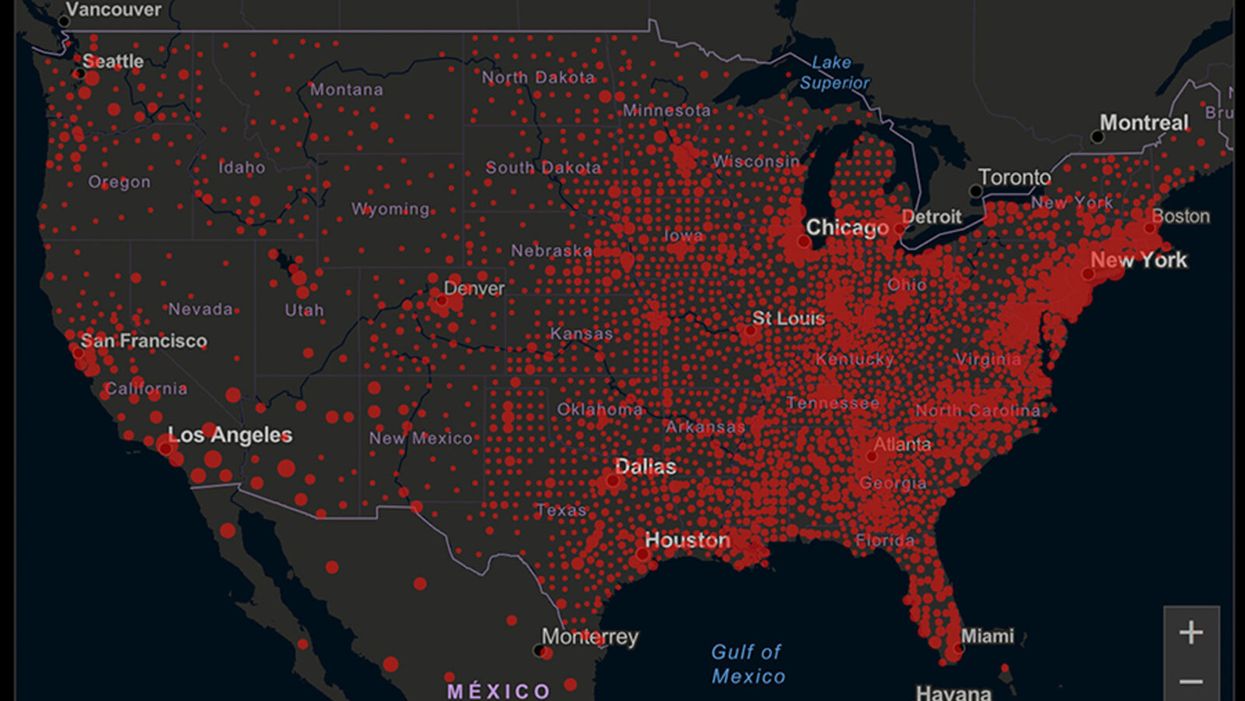

A map of cumulative known cases of COVID-19 in the U.S., as of June 12th, 2020.

Have you felt a bit like an armchair epidemiologist lately? Maybe you've been poring over coronavirus statistics on your county health department's website or on the pages of your local newspaper.

If the percentage of positive tests steadily stays under 8 percent, that's generally a good sign.

You're likely to find numbers and charts but little guidance about how to interpret them, let alone use them to make day-to-day decisions about pandemic safety precautions.

Enter the gurus. We asked several experts to provide guidance for laypeople about how to navigate the numbers. Here's a look at several common COVID-19 statistics along with tips about how to understand them.

Case Counts: Consider the Context

The number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in American counties is widely available. Local and state health departments should provide them online, or you can easily look them up at The New York Times' coronavirus database. However, you need to be cautious about interpreting them.

"Case counts are the obvious numbers to look at. But they're probably the hardest thing to sort out," said Dr. Jeff Martin, an epidemiologist at the University of California at San Francisco.

That's because case counts by themselves aren't a good window into how the coronavirus is affecting your community since they rely on testing. And testing itself varies widely from day to day and community to community.

"The more testing that's done, the more infections you'll pick up," explained Dr. F. Perry Wilson, a physician at Yale University. The numbers can also be thrown off when tests are limited to certain groups of people.

"If the tests are being mostly given to people with a high probability of having been infected -- for example, they have had symptoms or work in a high-risk setting -- then we expect lots of the tests to be positive. But that doesn't tell us what proportion of the general public is likely to have been infected," said Eleanor Murray, an epidemiologist at Boston University.

These Stats Are More Meaningful

According to Dr. Wilson, it's more useful to keep two other statistics in mind: the number of COVID tests that are being performed in your community and the percentage that turn up positive, showing that people have the disease. (These numbers may or may not be available locally. Check the websites of your community's health department and local news media outlets.)

If the number of people being tested is going up, but the percentage of positive tests is going down, Dr. Wilson said, that's a good sign. But if both numbers are going up – the number of people tested and the percentage of positive results – then "that's a sign that there are more infections burning in the community."

It's especially worrisome if the percentage of positive cases is growing compared to previous days or weeks, he said. According to him, that's a warning of a "high-risk situation."

Dr. George Rutherford, an epidemiologist at University of California at San Francisco, offered this tip: If the percentage of positive tests steadily stays under 8 percent, that's generally a good sign.

There's one more caveat about case counts. It takes an average of a week for someone to be infected with COVID-19, develop symptoms, and get tested, Dr. Rutherford said. It can take an additional several days for those test results to be reported to the county health department. This means that case numbers don't represent infections happening right now, but instead are a picture of the state of the pandemic more than a week ago.

Hospitalizations: Focus on Current Statistics

You should be able to find numbers about how many people in your community are currently hospitalized – or have been hospitalized – with diagnoses of COVID-19. But experts say these numbers aren't especially revealing unless you're able to see the number of new hospitalizations over time and track whether they're rising or falling. This number often isn't publicly available, however.

If new hospitalizations are increasing, "you may want to react by being more careful yourself."

And there's an important caveat: "The problem with hospitalizations is that they do lag," UC San Francisco's Dr. Martin said, since it takes time for someone to become ill enough to need to be hospitalized. "They tell you how much virus was being transmitted in your community 2 or 2.5 weeks ago."

Also, he said, people should be cautious about comparing new hospitalization rates between communities unless they're adjusted to account for the number of more-vulnerable older people.

Still, if new hospitalizations are increasing, he said, "you may want to react by being more careful yourself."

Deaths: They're an Even More Delayed Headline

Cable news networks obsessively track the number of coronavirus deaths nationwide, and death counts for every county in the country are available online. Local health departments and media websites may provide charts tracking the growth in deaths over time in your community.

But while death rates offer insight into the disease's horrific toll, they're not useful as an instant snapshot of the pandemic in your community because severely ill patients are typically sick for weeks. Instead, think of them as a delayed headline.

"These numbers don't tell you what's happening today. They tell you how much virus was being transmitted 3-4 weeks ago," Dr. Martin said.

'Reproduction Value': It May Be Revealing

You're not likely to find an available "reproduction value" for your community, but it is available for your state and may be useful.

A reproduction value, also known as R0 or R-naught, "tells us how many people on average we expect will be infected from a single case if we don't take any measures to intervene and if no one has been infected before," said Boston University's Murray.

As The New York Times explained, "R0 is messier than it might look. It is built on hard science, forensic investigation, complex mathematical models — and often a good deal of guesswork. It can vary radically from place to place and day to day, pushed up or down by local conditions and human behavior."

It may be impossible to find the R0 for your community. However, a website created by data specialists is providing updated estimates of a related number -- effective reproduction number, or Rt – for each state. (The R0 refers to how infectious the disease is in general and if precautions aren't taken. The Rt measures its infectiousness at a specific time – the "t" in Rt.) The site is at rt.live.

"The main thing to look at is whether the number is bigger than 1, meaning the outbreak is currently growing in your area, or smaller than 1, meaning the outbreak is currently decreasing in your area," Murray said. "It's also important to remember that this number depends on the prevention measures your community is taking. If the Rt is estimated to be 0.9 in your area and you are currently under lockdown, then to keep it below 1 you may need to remain under lockdown. Relaxing the lockdown could mean that Rt increases above 1 again."

"Whether they're on the upswing or downswing, no state is safe enough to ignore the precautions about mask wearing and social distancing."

Keep in mind that you can still become infected even if an outbreak in your community appears to be slowing. Low risk doesn't mean no risk.

Putting It All Together: Why the Numbers Matter

So you've reviewed COVID-19 statistics in your community. Now what?

Dr. Wilson suggests using the data to remind yourself that the coronavirus pandemic "is still out there. You need to take it seriously and continue precautions," he said. "Whether they're on the upswing or downswing, no state is safe enough to ignore the precautions about mask wearing and social distancing. 'My state is doing well, no one I know is sick, is it time to have a dinner party?' No."

He also recommends that laypeople avoid tracking COVID-19 statistics every day. "Check in once a week or twice a month to see how things are going," he suggested. "Don't stress too much. Just let it remind you to put that mask on before you get out of your car [and are around others]."

New tech aims to make the ocean healthier for marine life

Overabundance of dissolved carbon dioxide poses a threat to marine life. A new system detects elevated levels of the greenhouse gases and mitigates them on the spot.

A defunct drydock basin arched by a rusting 19th century steel bridge seems an incongruous place to conduct state-of-the-art climate science. But this placid and protected sliver of water connecting Brooklyn’s Navy Yard to the East River was just right for Garrett Boudinot to float a small dock topped with water carbon-sensing gear. And while his system right now looks like a trio of plastic boxes wired up together, it aims to mediate the growing ocean acidification problem, caused by overabundance of dissolved carbon dioxide.

Boudinot, a biogeochemist and founder of a carbon-management startup called Vycarb, is honing his method for measuring CO2 levels in water, as well as (at least temporarily) correcting their negative effects. It’s a challenge that’s been occupying numerous climate scientists as the ocean heats up, and as states like New York recognize that reducing emissions won’t be enough to reach their climate goals; they’ll have to figure out how to remove carbon, too.

To date, though, methods for measuring CO2 in water at scale have been either intensely expensive, requiring fancy sensors that pump CO2 through membranes; or prohibitively complicated, involving a series of lab-based analyses. And that’s led to a bottleneck in efforts to remove carbon as well.

But recently, Boudinot cracked part of the code for measurement and mitigation, at least on a small scale. While the rest of the industry sorts out larger intricacies like getting ocean carbon markets up and running and driving carbon removal at billion-ton scale in centralized infrastructure, his decentralized method could have important, more immediate implications.

Specifically, for shellfish hatcheries, which grow seafood for human consumption and for coastal restoration projects. Some of these incubators for oysters and clams and scallops are already feeling the negative effects of excess carbon in water, and Vycarb’s tech could improve outcomes for the larval- and juvenile-stage mollusks they’re raising. “We’re learning from these folks about what their needs are, so that we’re developing our system as a solution that’s relevant,” Boudinot says.

Ocean acidification can wreak havoc on developing shellfish, inhibiting their shells from growing and leading to mass die-offs.

Ocean waters naturally absorb CO2 gas from the atmosphere. When CO2 accumulates faster than nature can dissipate it, it reacts with H2O molecules, forming carbonic acid, H2CO3, which makes the water column more acidic. On the West Coast, acidification occurs when deep, carbon dioxide-rich waters upwell onto the coast. This can wreak havoc on developing shellfish, inhibiting their shells from growing and leading to mass die-offs; this happened, disastrously, at Pacific Northwest oyster hatcheries in 2007.

This type of acidification will eventually come for the East Coast, too, says Ryan Wallace, assistant professor and graduate director of environmental studies and sciences at Long Island’s Adelphi University, who studies acidification. But at the moment, East Coast acidification has other sources: agricultural runoff, usually in the form of nitrogen, and human and animal waste entering coastal areas. These excess nutrient loads cause algae to grow, which isn’t a problem in and of itself, Wallace says; but when algae die, they’re consumed by bacteria, whose respiration in turn bumps up CO2 levels in water.

“Unfortunately, this is occurring at the bottom [of the water column], where shellfish organisms live and grow,” Wallace says. Acidification on the East Coast is minutely localized, occurring closest to where nutrients are being released, as well as seasonally; at least one local shellfish farm, on Fishers Island in the Long Island Sound, has contended with its effects.

The second Vycarb pilot, ready to be installed at the East Hampton shellfish hatchery.

Courtesy of Vycarb

Besides CO2, ocean water contains two other forms of dissolved carbon — carbonate (CO3-) and bicarbonate (HCO3) — at all times, at differing levels. At low pH (acidic), CO2 prevails; at medium pH, HCO3 is the dominant form; at higher pH, CO3 dominates. Boudinot’s invention is the first real-time measurement for all three, he says. From the dock at the Navy Yard, his pilot system uses carefully calibrated but low-cost sensors to gauge the water’s pH and its corresponding levels of CO2. When it detects elevated levels of the greenhouse gas, the system mitigates it on the spot. It does this by adding a bicarbonate powder that’s a byproduct of agricultural limestone mining in nearby Pennsylvania. Because the bicarbonate powder is alkaline, it increases the water pH and reduces the acidity. “We drive a chemical reaction to increase the pH to convert greenhouse gas- and acid-causing CO2 into bicarbonate, which is HCO3,” Boudinot says. “And HCO3 is what shellfish and fish and lots of marine life prefers over CO2.”

This de-acidifying “buffering” is something shellfish operations already do to water, usually by adding soda ash (NaHCO3), which is also alkaline. Some hatcheries add soda ash constantly, just in case; some wait till acidification causes significant problems. Generally, for an overly busy shellfish farmer to detect acidification takes time and effort. “We’re out there daily, taking a look at the pH and figuring out how much we need to dose it,” explains John “Barley” Dunne, director of the East Hampton Shellfish Hatchery on Long Island. “If this is an automatic system…that would be much less labor intensive — one less thing to monitor when we have so many other things we need to monitor.”

Across the Sound at the hatchery he runs, Dunne annually produces 30 million hard clams, 6 million oysters, and “if we’re lucky, some years we get a million bay scallops,” he says. These mollusks are destined for restoration projects around the town of East Hampton, where they’ll create habitat, filter water, and protect the coastline from sea level rise and storm surge. So far, Dunne’s hatchery has largely escaped the ill effects of acidification, although his bay scallops are having a finicky year and he’s checking to see if acidification might be part of the problem. But “I think it's important to have these solutions ready-at-hand for when the time comes,” he says. That’s why he’s hosting a second, 70-liter Vycarb pilot starting this summer on a dock adjacent to his East Hampton operation; it will amp up to a 50,000 liter-system in a few months.

If it can buffer water over a large area, absolutely this will benefit natural spawns. -- John “Barley” Dunne.

Boudinot hopes this new pilot will act as a proof of concept for hatcheries up and down the East Coast. The area from Maine to Nova Scotia is experiencing the worst of Atlantic acidification, due in part to increased Arctic meltwater combining with Gulf of St. Lawrence freshwater; that decreases saturation of calcium carbonate, making the water more acidic. Boudinot says his system should work to adjust low pH regardless of the cause or locale. The East Hampton system will eventually test and buffer-as-necessary the water that Dunne pumps from the Sound into 100-gallon land-based tanks where larvae grow for two weeks before being transferred to an in-Sound nursery to plump up.

Dunne says this could have positive effects — not only on his hatchery but on wild shellfish populations, too, reducing at least one stressor their larvae experience (others include increasing water temperatures and decreased oxygen levels). “If it can buffer water over a large area, absolutely this will [benefit] natural spawns,” he says.

No one believes the Vycarb model — even if it proves capable of functioning at much greater scale — is the sole solution to acidification in the ocean. Wallace says new water treatment plants in New York City, which reduce nitrogen released into coastal waters, are an important part of the equation. And “certainly, some green infrastructure would help,” says Boudinot, like restoring coastal and tidal wetlands to help filter nutrient runoff.

In the meantime, Boudinot continues to collect data in advance of amping up his own operations. Still unknown is the effect of releasing huge amounts of alkalinity into the ocean. Boudinot says a pH of 9 or higher can be too harsh for marine life, plus it can also trigger a release of CO2 from the water back into the atmosphere. For a third pilot, on Governor’s Island in New York Harbor, Vycarb will install yet another system from which Boudinot’s team will frequently sample to analyze some of those and other impacts. “Let's really make sure that we know what the results are,” he says. “Let's have data to show, because in this carbon world, things behave very differently out in the real world versus on paper.”

Many children use makeup and body products such as glitter, face paint and lip gloss. Scientists are pointing to the harmful chemicals in some of these products, and advocates are looking to outlaw them.

When Erika Schreder’s 14-year-old daughter, who is Black, had her curly hair braided at a Seattle-area salon two or three times recently, the hairdresser applied a styling gel to seal the tresses in place.

Schreder and her daughter had been trying to avoid harmful chemicals, so they were shocked to later learn that this particular gel had the highest level of formaldehyde of any product tested by the Washington State Departments of Ecology and Health. In January 2023, the agencies released a report that uncovered high levels of formaldehyde in certain hair products, creams and lotions marketed to or used by people of color. When Schreder saw the report, she mentioned it to her daughter, who told her the name of the gel smoothed on her hair.

“It was really upsetting,” said Schreder, science director at Toxic-Free Future, a Seattle-based nonprofit environmental health research and advocacy organization. “Learning that this product used on my daughter’s hair contained cancer-causing formaldehyde made me even more committed to advocating for our state to ban toxic ingredients in cosmetics and personal care products.”

In 2013, Toxic-Free Future launched Mind the Store to challenge the nation’s largest retailers in adopting comprehensive policies that eliminate toxic chemicals in their personal care products and packaging, and develop safer alternatives.

Now, more efforts are underway to expose and mitigate the harm in cosmetics, hair care and other products that children apply on their faces, heads, nails and other body parts. Advocates hope to raise awareness among parents while prompting manufacturers and salon professionals to adopt safer alternatives.

A recent study by researchers at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and Earthjustice, a San Francisco-based nonprofit public interest environmental law organization, revealed that most children in the United States use makeup and body products that may contain carcinogens and other toxic chemicals. In January, the results were published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. Based on more than 200 surveys, 70 percent of parents in the study reported that their children 12 or younger have used makeup and body products marketed to youth — for instance, glitter, face paint and lip gloss.

Childhood exposure to harmful makeup and body product ingredients can also be considered an environmental justice issue, as communities of color may be more likely to use these products.

“We are concerned about exposure to chemicals that may be found in cosmetics and body products, including those that are marketed toward children,” said the study’s senior author, Julie Herbstman, a professor and director of the Columbia Center for Children's Environmental Health. The goal of the survey was to try to understand how much kids are using cosmetic and body products and when, how and why they are using them.

“There is widespread use of children’s cosmetic and body products, and kids are using them principally to play,” Herbstman said. “That’s really quite different than how adults use cosmetic and body products.” Even with products that are specifically designed for children, “there’s no regulation that ensures that these products are safe for kids.” Also, she said, some children are using adult products — and they may do so in inadvisable ways, such as ingesting lipstick or applying it to other areas of the face.

Earlier research demonstrated that beauty and personal care products manufactured for children and adults frequently contain toxic chemicals, such as lead, asbestos, PFAS, phthalates and formaldehyde. Heavy metals and other toxic chemicals in children’s makeup and body products are particularly harmful to infants and youth, who are growing rapidly and whose bodies are less efficient at metabolizing these chemicals. Whether these chemicals are added intentionally or are present as contaminants, they have been associated with cancer, neurodevelopmental harm, and other serious and irreversible health effects, the Columbia University and Earthjustice researchers noted.

“Even when concentrations of individual chemicals are low in products, the potential for interactive effects from multiple toxicants is important to take into consideration,” the authors wrote in the journal article. “Allergic reactions, such as contact dermatitis, are some of the most frequently cited negative health outcomes associated with the use of cosmetics.”

Children’s small body side, rapid growth rate and immature immune systems are biologically more prone to the effects of toxicants than adults.

Adobe Stock

In addition to children’s rapid growth rate, the study also reported that their small body size, developing tissues and organs, and immature immune systems are biologically more prone to the effects of toxicants than adults. Meanwhile, the study noted, “childhood exposure to harmful makeup and body product ingredients can also be considered an environmental justice issue, as communities of color may be more likely to use these products.”

Although adults are the typical users of cosmetics, similar items are heavily marketed to youth with attention-grabbing features such as bright colors, animals and cartoon characters, according to the study. Beyond conventional makeup such as eyeshadow and lipstick, children may apply face paint, body glitter, nail polish, hair gel and fragrances. They also may frequent social media platforms on which these products are increasingly being promoted.

Products for both children and adults are currently regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938. Also, the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act of 1967 directs the Federal Trade Commission and the FDA “to issue regulations requiring that all ‘consumer commodities’ be labeled to disclose net contents, identity of commodity, and name and place of business of the product's manufacturer, packer, or distributor.” As the Columbia University and Earthjustice authors pointed out, though, “current safety regulations have been widely criticized as inadequate.”

The Personal Care Products Council in Washington, D.C., “fundamentally disagrees with the premise that companies put toxic chemicals in products produced for children,” industry spokeswoman Lisa Powers said in an email. Founded in 1894, the national trade association represents 600 member companies that manufacture, distribute and supply most personal care products marketed in the United States.

No category of consumer products is subject to less government oversight than cosmetics and other personal care products. -- Environmental Working Group.

“Science and safety are the cornerstones of our industry,” Powers stated. For more than a decade, she wrote, “the [Council] and our member companies worked diligently with a bipartisan group of congressional leaders and a diverse group of stakeholders to enhance the effectiveness of the FDA regulatory authority and to provide the safety reassurances that consumers expect and deserve.”

Powers added that the “industry employs and consults thousands of scientific and medical experts” who study the impacts of cosmetics and personal care products and the ingredients used in them. The Council also maintains a comprehensive database where consumers can look up science and safety information on the thousands of ingredients in sunscreens, toothpaste, shampoo, moisturizer, makeup, fragrances and other products.

However, the Environmental Working Group, which empowers consumers with breakthrough research to make informed choices about healthy living, believes the regulations are still not robust enough. “No category of consumer products is subject to less government oversight than cosmetics and other personal care products,” states the organization’s website. “Although many of the chemicals and contaminants in cosmetics and personal care products likely pose little risk, exposure to some has been linked to serious health problems, including cancer.”

The group, which operates the Skin Deep Database noted that “since 2009, 595 cosmetics manufacturers have reported using 88 chemicals, in more than 73,000 products, that have been linked to cancer, birth defects or reproductive harm.”

But change, for both adults and kids, is on the horizon. The Modernization of Cosmetics Regulation Act of 2022 significantly expanded the FDA’s authority to regulate cosmetics. In May 2023, Washington state adopted a law regulating cosmetics and personal care products. The Toxic-Free Cosmetics Act (HB 1047) bans chemicals in beauty and personal care products, such as PFAS, lead, mercury, phthalates and formaldehyde-releasing agents. These bans take effect in 2025, except for formaldehyde releasers, which have a phased-in approach starting in 2026.

Industry and advocates view this as a positive development. Powers, the spokesperson, praised “the long-awaited” Modernization Cosmetics Regulation Act of 2022, which she said, “advances product safety and innovation.” Jen Lee, chief impact officer at Beautycoutner, a company that sells personal care products, also welcomes the change. “We were proud to support the Washington Toxic-Free Cosmetics Act (HB 1047) by mobilizing our community of Brand Advocates who reside in Washington State,” Lee said. “Together, they made their voices heard by sending over 1,000 emails to their state legislators urging them to support and pass the bill.”

Laurie Valeriano, executive director of Toxic-Free Future, praised the upcoming Washington state law as “a huge win for public health and the environment that will have impacts that ripple across the nation.” She added that “companies won’t make special products for Washington state.” Instead, “they will reformulate and make products safer for everyone” — adults and children.

You shouldn’t have to be a toxicologist to shop for shampoo. -- Washington State Rep. Sharlett Mena

The new legislation will require Washington state agencies to assess the hazards of chemicals used in products that can impact vulnerable populations, while providing support for small businesses and independent cosmetologists to transition to safer products.

The Toxic-Free Future team lauds the Cosmetics Act, signed in May 2023.

Courtesy Toxic-Free Future

“When we go to a store, we assume the products on the shelf are safe, but this isn’t always true,” said Washington State Rep. Sharlett Mena, a Democrat serving in the 29th Legislative District (Tacoma), who sponsored the law. “I introduced this bill (HB 1047) because currently, the burden is on the consumer to navigate labels and find safe alternatives. You shouldn’t have to be a toxicologist to shop for shampoo.”

The new law aims to protect people of all ages, but especially youth. “Children are more susceptible to the impacts of toxic chemicals because their bodies are still developing,” Mena said. “Lead, for example, is significantly more hazardous to children than adults. Also, since children, unlike adults, tend to put things in their mouths all the time, they are more exposed to harmful chemicals in personal care and other products.”

Cosmetologists and hair professionals are taking notice. “Safety should be the practitioner’s number one concern” in using products on small children, said Anwar Saleem, a hair stylist, instructor and former salon owner in Washington, D.C., who is chairman of the D.C. Board of Barbering and Cosmetology and president of the National Interstate Council of State Boards of Cosmetology. “There are so many products on the market that it can be confusing.”

Hair products designed and labeled for children's use often have milder formulations, but “every child is unique, and what works for one may not work for another,” Saleem said. He recommends doing a patch test, in which the stylist or cosmetologist dabs the product on a small, inconspicuous area of the scalp or skin and waits anywhere from an hour to a day to check for irritation before continuing to serve the client. “Performing a patch test, observing children's reactions to a product and adequately adjusting are essential.”

Saleem seeks products that are free from harsh chemicals such as sulfates, phthalates and parabens, noting that these ingredients can be irritating and drying to the hair and scalp. If a child has sensitive skin or allergies, Saleem opts for hypoallergenic products.

We also need to ensure that less toxic alternatives are available and accessible to all consumers. It’s often under-resourced, low-income populations who suffer the burden of environmental exposures and do not have access or cannot afford these safer alternatives. -- Lesliam Quirós-Alcalá.

Lesliam Quirós-Alcalá, an assistant professor in the department of environmental health and engineering at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said current regulatory loopholes on product labeling still allow manufacturers to advertise their cosmetics and personal care products as “gentle” and “natural.” However, she said, those terms may be misleading as they don’t necessarily mean the contents are less toxic or harmful to consumers.

“We also need to ensure that less toxic alternatives are available and accessible to all consumers,” Quirós-Alcalá said, “as often alternatives considered to be less toxic come with a hefty price tag.” As a result, “it’s often under-resourced, low-income populations who suffer the burden of environmental exposures and do not have access or cannot afford these safer alternatives.”

To advocate for safer alternatives, Quirós-Alcalá suggests that parents turn to consumer groups involved in publicizing the harms of personal care products. The Campaign for Safe Cosmetics is a program of Breast Cancer Prevention Partners, a national science-based advocacy organization aiming to prevent the disease by eliminating related environmental exposures. Other resources that inform users about unsafe ingredients include the mobile apps Clearya and Think Dirty.

“Children are not little adults, so it’s important to increase parent and consumer awareness to minimize their exposures to toxic chemicals in everyday products,” Quirós-Alcalá said. “Becoming smarter, more knowledgeable consumers is the first step to protecting your family from potentially harmful and toxic ingredients in consumer products.”