Don’t fear AI, fear power-hungry humans

Story by Big Think

We live in strange times, when the technology we depend on the most is also that which we fear the most. We celebrate cutting-edge achievements even as we recoil in fear at how they could be used to hurt us. From genetic engineering and AI to nuclear technology and nanobots, the list of awe-inspiring, fast-developing technologies is long.

However, this fear of the machine is not as new as it may seem. Technology has a longstanding alliance with power and the state. The dark side of human history can be told as a series of wars whose victors are often those with the most advanced technology. (There are exceptions, of course.) Science, and its technological offspring, follows the money.

This fear of the machine seems to be misplaced. The machine has no intent: only its maker does. The fear of the machine is, in essence, the fear we have of each other — of what we are capable of doing to one another.

How AI changes things

Sure, you would reply, but AI changes everything. With artificial intelligence, the machine itself will develop some sort of autonomy, however ill-defined. It will have a will of its own. And this will, if it reflects anything that seems human, will not be benevolent. With AI, the claim goes, the machine will somehow know what it must do to get rid of us. It will threaten us as a species.

Well, this fear is also not new. Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein in 1818 to warn us of what science could do if it served the wrong calling. In the case of her novel, Dr. Frankenstein’s call was to win the battle against death — to reverse the course of nature. Granted, any cure of an illness interferes with the normal workings of nature, yet we are justly proud of having developed cures for our ailments, prolonging life and increasing its quality. Science can achieve nothing more noble. What messes things up is when the pursuit of good is confused with that of power. In this distorted scale, the more powerful the better. The ultimate goal is to be as powerful as gods — masters of time, of life and death.

Should countries create a World Mind Organization that controls the technologies that develop AI?

Back to AI, there is no doubt the technology will help us tremendously. We will have better medical diagnostics, better traffic control, better bridge designs, and better pedagogical animations to teach in the classroom and virtually. But we will also have better winnings in the stock market, better war strategies, and better soldiers and remote ways of killing. This grants real power to those who control the best technologies. It increases the take of the winners of wars — those fought with weapons, and those fought with money.

A story as old as civilization

The question is how to move forward. This is where things get interesting and complicated. We hear over and over again that there is an urgent need for safeguards, for controls and legislation to deal with the AI revolution. Great. But if these machines are essentially functioning in a semi-black box of self-teaching neural nets, how exactly are we going to make safeguards that are sure to remain effective? How are we to ensure that the AI, with its unlimited ability to gather data, will not come up with new ways to bypass our safeguards, the same way that people break into safes?

The second question is that of global control. As I wrote before, overseeing new technology is complex. Should countries create a World Mind Organization that controls the technologies that develop AI? If so, how do we organize this planet-wide governing board? Who should be a part of its governing structure? What mechanisms will ensure that governments and private companies do not secretly break the rules, especially when to do so would put the most advanced weapons in the hands of the rule breakers? They will need those, after all, if other actors break the rules as well.

As before, the countries with the best scientists and engineers will have a great advantage. A new international détente will emerge in the molds of the nuclear détente of the Cold War. Again, we will fear destructive technology falling into the wrong hands. This can happen easily. AI machines will not need to be built at an industrial scale, as nuclear capabilities were, and AI-based terrorism will be a force to reckon with.

So here we are, afraid of our own technology all over again.

What is missing from this picture? It continues to illustrate the same destructive pattern of greed and power that has defined so much of our civilization. The failure it shows is moral, and only we can change it. We define civilization by the accumulation of wealth, and this worldview is killing us. The project of civilization we invented has become self-cannibalizing. As long as we do not see this, and we keep on following the same route we have trodden for the past 10,000 years, it will be very hard to legislate the technology to come and to ensure such legislation is followed. Unless, of course, AI helps us become better humans, perhaps by teaching us how stupid we have been for so long. This sounds far-fetched, given who this AI will be serving. But one can always hope.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.

How a Deadly Fire Gave Birth to Modern Medicine

The Cocoanut Grove fire in Boston in 1942 tragically claimed 490 lives, but was the catalyst for several important medical advances.

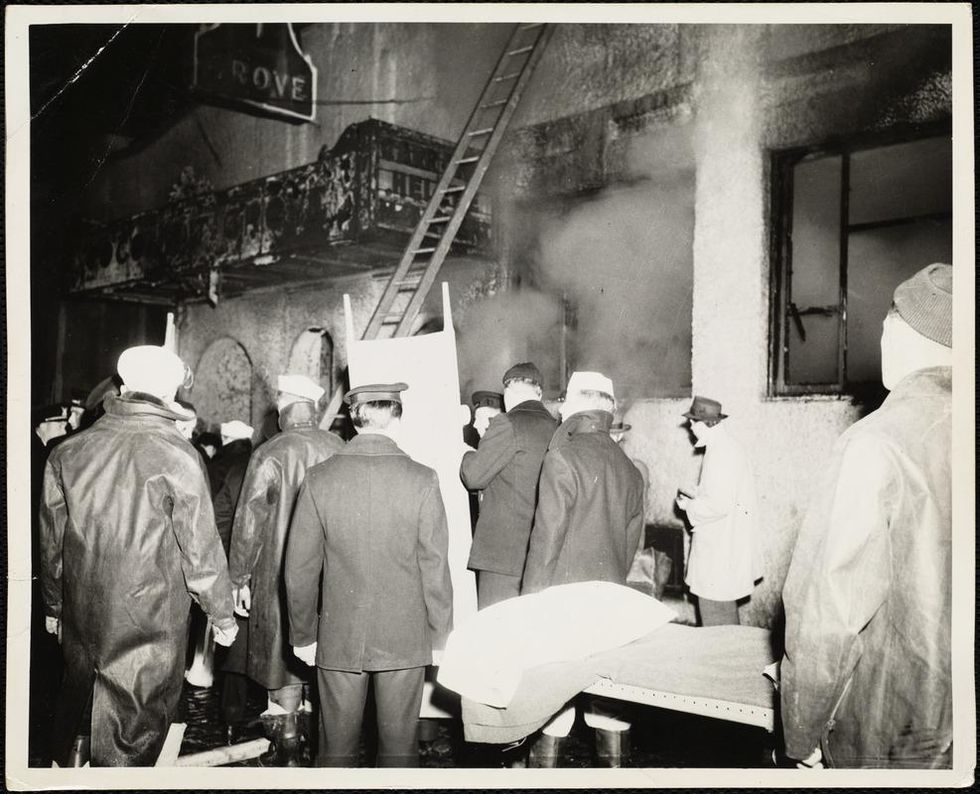

On the evening of November 28, 1942, more than 1,000 revelers from the Boston College-Holy Cross football game jammed into the Cocoanut Grove, Boston's oldest nightclub. When a spark from faulty wiring accidently ignited an artificial palm tree, the packed nightspot, which was only designed to accommodate about 500 people, was quickly engulfed in flames. In the ensuing panic, hundreds of people were trapped inside, with most exit doors locked. Bodies piled up by the only open entrance, jamming the exits, and 490 people ultimately died in the worst fire in the country in forty years.

"People couldn't get out," says Dr. Kenneth Marshall, a retired plastic surgeon in Boston and president of the Cocoanut Grove Memorial Committee. "It was a tragedy of mammoth proportions."

Within a half an hour of the start of the blaze, the Red Cross mobilized more than five hundred volunteers in what one newspaper called a "Rehearsal for Possible Blitz." The mayor of Boston imposed martial law. More than 300 victims—many of whom subsequently died--were taken to Boston City Hospital in one hour, averaging one victim every eleven seconds, while Massachusetts General Hospital admitted 114 victims in two hours. In the hospitals, 220 victims clung precariously to life, in agonizing pain from massive burns, their bodies ravaged by infection.

The scene of the fire.

Boston Public Library

Tragic Losses Prompted Revolutionary Leaps

But there is a silver lining: this horrific disaster prompted dramatic changes in safety regulations to prevent another catastrophe of this magnitude and led to the development of medical techniques that eventually saved millions of lives. It transformed burn care treatment and the use of plasma on burn victims, but most importantly, it introduced to the public a new wonder drug that revolutionized medicine, midwifed the birth of the modern pharmaceutical industry, and nearly doubled life expectancy, from 48 years at the turn of the 20th century to 78 years in the post-World War II years.

The devastating grief of the survivors also led to the first published study of post-traumatic stress disorder by pioneering psychiatrist Alexandra Adler, daughter of famed Viennese psychoanalyst Alfred Adler, who was a student of Freud. Dr. Adler studied the anxiety and depression that followed this catastrophe, according to the New York Times, and "later applied her findings to the treatment World War II veterans."

Dr. Ken Marshall is intimately familiar with the lingering psychological trauma of enduring such a disaster. His mother, an Irish immigrant and a nurse in the surgical wards at Boston City Hospital, was on duty that cold Thanksgiving weekend night, and didn't come home for four days. "For years afterward, she'd wake up screaming in the middle of the night," recalls Dr. Marshall, who was four years old at the time. "Seeing all those bodies lined up in neat rows across the City Hospital's parking lot, still in their evening clothes. It was always on her mind and memories of the horrors plagued her for the rest of her life."

The sheer magnitude of casualties prompted overwhelmed physicians to try experimental new procedures that were later successfully used to treat thousands of battlefield casualties. Instead of cutting off blisters and using dyes and tannic acid to treat burned tissues, which can harden the skin, they applied gauze coated with petroleum jelly. Doctors also refined the formula for using plasma--the fluid portion of blood and a medical technology that was just four years old--to replenish bodily liquids that evaporated because of the loss of the protective covering of skin.

"Every war has given us a new medical advance. And penicillin was the great scientific advance of World War II."

"The initial insult with burns is a loss of fluids and patients can die of shock," says Dr. Ken Marshall. "The scientific progress that was made by the two institutions revolutionized fluid management and topical management of burn care forever."

Still, they could not halt the staph infections that kill most burn victims—which prompted the first civilian use of a miracle elixir that was being secretly developed in government-sponsored labs and that ultimately ushered in a new age in therapeutics. Military officials quickly realized this disaster could provide an excellent natural laboratory to test the effectiveness of this drug and see if it could be used to treat the acute traumas of combat in this unfortunate civilian approximation of battlefield conditions. At the time, the very existence of this wondrous medicine—penicillin—was a closely guarded military secret.

From Forgotten Lab Experiment to Wonder Drug

In 1928, Alexander Fleming discovered the curative powers of penicillin, which promised to eradicate infectious pathogens that killed millions every year. But the road to mass producing enough of the highly unstable mold was littered with seemingly unsurmountable obstacles and it remained a forgotten laboratory curiosity for over a decade. But Fleming never gave up and penicillin's eventual rescue from obscurity was a landmark in scientific history.

In 1940, a group at Oxford University, funded in part by the Rockefeller Foundation, isolated enough penicillin to test it on twenty-five mice, which had been infected with lethal doses of streptococci. Its therapeutic effects were miraculous—the untreated mice died within hours, while the treated ones played merrily in their cages, undisturbed. Subsequent tests on a handful of patients, who were brought back from the brink of death, confirmed that penicillin was indeed a wonder drug. But Britain was then being ravaged by the German Luftwaffe during the Blitz, and there were simply no resources to devote to penicillin during the Nazi onslaught.

In June of 1941, two of the Oxford researchers, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, embarked on a clandestine mission to enlist American aid. Samples of the temperamental mold were stored in their coats. By October, the Roosevelt Administration had recruited four companies—Merck, Squibb, Pfizer and Lederle—to team up in a massive, top-secret development program. Merck, which had more experience with fermentation procedures, swiftly pulled away from the pack and every milligram they produced was zealously hoarded.

After the nightclub fire, the government ordered Merck to dispatch to Boston whatever supplies of penicillin that they could spare and to refine any crude penicillin broth brewing in Merck's fermentation vats. After working in round-the-clock relays over the course of three days, on the evening of December 1st, 1942, a refrigerated truck containing thirty-two liters of injectable penicillin left Merck's Rahway, New Jersey plant. It was accompanied by a convoy of police escorts through four states before arriving in the pre-dawn hours at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dozens of people were rescued from near-certain death in the first public demonstration of the powers of the antibiotic, and the existence of penicillin could no longer be kept secret from inquisitive reporters and an exultant public. The next day, the Boston Globe called it "priceless" and Time magazine dubbed it a "wonder drug."

Within fourteen months, penicillin production escalated exponentially, churning out enough to save the lives of thousands of soldiers, including many from the Normandy invasion. And in October 1945, just weeks after the Japanese surrender ended World War II, Alexander Fleming, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain were awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine. But penicillin didn't just save lives—it helped build some of the most innovative medical and scientific companies in history, including Merck, Pfizer, Glaxo and Sandoz.

"Every war has given us a new medical advance," concludes Marshall. "And penicillin was the great scientific advance of World War II."

This Boy Struggled to Walk Before Gene Therapy. Now, Such Treatments Are Poised to Explode.

Conner Curran, now 10 years old, can walk more than two miles after gene therapy treatment for his Duchenne's muscular dystrophy.

Conner Curran was diagnosed with Duchenne's muscular dystrophy in 2015 when he was four years old. It's the most severe form of the genetic disease, with a nearly inevitable progression toward total paralysis. Many Duchenne's patients die in their teens; the average lifespan is 26.

But Conner, who is now 10, has experienced some astonishing improvements in recent years. He can now walk for more than two miles at a time – an impossible journey when he was younger.

In 2018, Conner became the very first patient to receive gene therapy specific to treating Duchenne's. In the initial clinical trial of nine children, nearly 80 percent reacted positively to the treatment). A larger-scale stage 3 clinical trial is currently underway, with initial results expected next year.

Gene therapy involves altering the genes in an individual's cells to stop or treat a disease. Such a procedure may be performed by adding new gene material to existing cells, or editing the defective genes to improve their functionality.

That the medical world is on the cusp of a successful treatment for a crippling and deadly disease is the culmination of more than 35 years of work by Dr. Jude Samulski, a professor of pharmacology at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill. More recently, he's become a leading gene therapy entrepreneur.

But Samulski likens this breakthrough to the frustrations of solving a Rubik's cube. "Just because one side is now all the color yellow does not mean that it is completely aligned," he says.

Although Conner's life and future have dramatically improved, he's not cured. The gene therapy tamed but did not extinguish his disorder: Conner is now suffering from the equivalent of Becker's muscular dystrophy, a milder form of the disease with symptoms that appear later in life and progress more slowly. Moreover, the loss of muscle cells Conner suffered prior to the treatment is permanent.

"It will take more time and more innovations," Samulski says of finding an even more effective gene therapy for muscular dystrophy.

Conner's family is still overjoyed with the results. "Jude's grit and determination gave Conner a chance at a new life, one that was not in his cards before gene therapy," says his mother Jessica Curran. She adds that "Conner is more confident than before and enjoys life, even though he has limitations, if compared to his brothers or peers."

Conner Curran holding a football post gene therapy treatment.

Courtesy of the Curran family

For now, the use of gene therapy as a treatment for diseases and disorders remains relatively isolated. On paper at least, progress appears glacially slow. In 2018, there were four FDA-approved gene therapies (excluding those reliant on bone marrow/stem cell transplants or implants). Today, there are 10. One therapy is solely for the cosmetic purpose of reducing facial lines and folds.

Nevertheless, experts in the space believe gene therapy is poised to expand dramatically.

"Certainly in the next three to five years you will see dozens of gene therapies and cell therapies be approved," says Dr. Pavan Cheruvu, who is CEO of Sio Gene Therapies in New York. The company is developing treatments for Parkinson's disease and Tay-Sachs, among other diseases.

Cheruvu's conclusion is supported by NEWDIGS, a think tank at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology that keeps tabs on gene therapy developments. NEWDIGS predicts there will be at least 60 gene therapies approved for use in the U.S. by the end of the decade. That number could be closer to 100 if Chinese researchers and biotech ventures decide the American market is a good fit for the therapies they develop.

"We are watching something of a conditional evolution, like a dot-com, or cellphones that were sizes of shoeboxes that have now matured to the size of wafers. Our space will follow along very similarly."

Dr. Carsten Brunn, a chemist by training and CEO of Selecta Biosciences outside of Boston, is developing ways to reduce the immune responses in patients who receive gene therapy. He observes that there are more than 300 therapies in development and thousands of clinical trials underway. "It's definitely an exciting time in the field," he says.

That's a far cry from the environment of little more than a decade ago. Research and investment in gene therapy had been brought low for years after the death of teenager Jesse Gelsinger in 1999 while he had been enrolled in a clinical trial to treat a liver disease. Gene therapy was a completely novel concept back then, and his death created existential questions about whether it was a proper pathway to pursue. Cheruvu, a cardiologist, calls the years after Gelsinger's death an "ice age" for gene therapy.

However, those dark years eventually yielded to a thaw. And while there have been some recent stumbles, they are considered part of the trial-and-error that has often accompanied medical research as opposed to an ominous "stop" sign.

The deaths of three patients last year receiving gene therapy for myotubular myopathy – a degenerative disease that causes severe muscle weakness – promptly ended the clinical trial in which they were enrolled. However, the incident caused few ripples beyond that. Researchers linked the deaths to dosage sizes that caused liver toxicity, as opposed to the gene therapy itself being an automatic death sentence; younger patients who received lower doses due to a less advanced disease state experienced improvements.

The gene sequencing and editing that helped create vaccines for COVID-19 in record time also bolstered the argument for more investment in research and development. Cheruvu notes that the field has usually been the domain of investors with significant expertise in the field; these days, more money is flowing in from generalists.

The Challenges Ahead

What will be the next step in gene therapy's evolution? Many of Samulski's earliest innovations came in the laboratory, for example. Then that led to him forming a company called AskBio in collaboration with the Muscular Dystrophy Association. AskBio sold its gene therapy to Pfizer five years ago to assure that enough could be manufactured for stage 3 clinical trials and eventually reach the market.

Cheruvu suggests that many future gene therapy innovations will be the result of what he calls "congruent innovation." That means publicly funded laboratories and privately funded companies might develop treatments separately or in collaboration. Or, university scientists may depend on private ventures to solve one of gene therapy's most vexing issues: producing enough finished material to test and treat on a large scale. "Manufacturing is a real bottleneck right now," Brunn says.

The alternative is referred to in the sector as the "valley of death": a lab has found a promising treatment, but is not far enough along in development to submit an investigational new drug application with the FDA. The promise withers away as a result. But the new abundance of venture capital for gene therapy has made this scenario less of an issue for private firms, some of which have received hundreds of millions of dollars in funding.

There are also numerous clinical challenges. Many gene therapies use what are known as adeno-associated virus vectors (AAVs) to deliver treatments. They are hollowed-out husks of viruses that can cause a variety of mostly mild maladies ranging from colds to pink eye. They are modified to deliver the genetic material used in the therapy. Most of these vectors trigger an antibody reaction that limits treatments to a single does or a handful of smaller ones. That can limit the potential progress for patients – an issue referred to as treatment "durability."

Although vectors from animals such as horses trigger far less of an antibody reaction in patients -- and there has been significant work done on using artificial vectors -- both are likely years away from being used on a large scale. "For the foreseeable future, AAV is the delivery system of choice," Brunn says.

Also, there will likely be demand for concurrent gene therapies that can lead to a complete cure – not only halting the progress of Duchenne's in kids like Conner Curran, but regenerating their lost muscle cells, perhaps through some form of stem cell therapy or another treatment that has yet to be devised.

Nevertheless, Samulski believes demand for imperfect treatments will be high – particularly with a disease such as muscular dystrophy, where many patients are mere months from spending the remainder of their lives in wheelchairs. But Samulski believes those therapies will also inevitably evolve into something far more effective.

"We are watching something of a conditional evolution, like a dot-com, or cellphones that were sizes of shoeboxes that have now matured to the size of wafers," he says. "Our space will follow along very similarly."

Jessica Curran will remain forever grateful for what her son has received: "Jude gave us new hope. He gave us something that is priceless – a chance to watch Conner grow up and live out his own dreams."