As More People Crowdfund Medical Bills, Beware of Dubious Campaigns

Individuals seeking funding for experimental therapies may enroll in legitimate clinical trials -- or fall prey to snake oil.

Nearly a decade ago, Jamie Anderson hit his highest weight ever: 618 pounds. Depression drove him to eat and eat. He tried all kinds of diets, losing and regaining weight again and again. Then, four years ago, a friend nudged him to join a gym, and with a trainer's guidance, he embarked on a life-altering path.

Ethicists become particularly alarmed when medical crowdfunding appeals are for scientifically unfounded and potentially harmful interventions.

"The big catalyst for all of this is, I was diagnosed as a diabetic," says Anderson, a 46-year-old sales associate in the auto care department at Walmart. Within three years, he was down to 276 pounds but left with excess skin, which sagged from his belly to his mid-thighs.

Plastic surgery would cost $4,000 more than the sum his health insurance approved. That's when Anderson, who lives in Cabot, Arkansas, a suburb outside of Little Rock, turned to online crowdfunding to raise money. In a few months last year, current and former co-workers and friends of friends came up with that amount, covering the remaining expenses for the tummy tuck and overnight hospital stay.

The crowdfunding site that he used, CoFund Health, aimed to give his donors some peace of mind about where their money was going. Unlike GoFundMe and other platforms that don't restrict how donations are spent, Anderson's funds were loaded on a debit card that only worked at health care providers, so the donors "were assured that it was for medical bills only," he says.

CoFund Health was started in January 2019 in response to concerns about the legitimacy of many medical crowdfunding campaigns. As crowdfunding for health-related expenses has gained more traction on social media sites, with countless campaigns seeking to subsidize the high costs of care, it has given rise to some questionable transactions and legitimate ethical concerns.

Common examples of alleged fraud have involved misusing the donations for nonmedical purposes, feigning or embellishing the story of one's own unfortunate plight or that of another person, or impersonating someone else with an illness. Ethicists become particularly alarmed when medical crowdfunding appeals are for scientifically unfounded and potentially harmful interventions.

About 20 percent of American adults reported giving to a crowdfunding campaign for medical bills or treatments, according to a survey by AmeriSpeak Spotlight on Health from NORC, formerly called the National Opinion Research Center, a non-partisan research institution at the University of Chicago. The self-funded poll, conducted in November 2019, included 1,020 interviews with a representative sample of U.S. households. Researchers cited a 2019 City University of New York-Harvard study, which noted that medical bills are the most common basis for declaring personal bankruptcy.

Some experts contend that crowdfunding platforms should serve as gatekeepers in prohibiting campaigns for unproven treatments. Facing a dire diagnosis, individuals may go out on a limb to try anything and everything to prolong and improve the quality of their lives.

They may enroll in well-designed clinical trials, or they could fall prey "to snake oil being sold by people out there just making a buck," says Jeremy Snyder, a health sciences professor at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, Canada, and the lead author of a December 2019 article in The Hastings Report about crowdfunding for dubious treatments.

For instance, crowdfunding campaigns have sought donations for homeopathic healing for cancer, unapproved stem cell therapy for central nervous system injury, and extended antibiotic use for chronic Lyme disease, according to an October 2018 report in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Ford Vox, the lead author and an Atlanta-based physician specializing in brain injury, maintains that a repository should exist to monitor the outcomes of experimental treatments. "At the very least, there ought to be some tracking of what happens to the people the funds are being raised for," he says. "It would be great for an independent organization to do so."

"Even if it appears like a good cause, consumers should still do some research before donating to a crowdfunding campaign."

The Federal Trade Commission, the national consumer watchdog, cautions online that "it might be impossible for you to know if the cause is real and if the money actually gets to the intended recipient." Another caveat: Donors can't deduct contributions to individuals on tax returns.

"Even if it appears like a good cause, consumers should still do some research before donating to a crowdfunding campaign," says Malini Mithal, associate director of financial practices at the FTC. "Don't assume all medical treatments are tested and safe."

Before making any donation, it would be wise to check whether a crowdfunding site offers some sort of guarantee if a campaign ends up being fraudulent, says Kristin Judge, chief executive and founder of the Cybercrime Support Network, a Michigan-based nonprofit that serves victims before, during, and after an incident. They should know how the campaign organizer is related to the intended recipient and note whether any direct family members and friends have given funds and left supportive comments.

Donating to vetted charities offers more assurance than crowdfunding that the money will be channeled toward helping someone in need, says Daniel Billingsley, vice president of external affairs for the Oklahoma Center of Nonprofits. "Otherwise, you could be putting money into all sorts of scams." There is "zero accountability" for the crowdfunding site or the recipient to provide proof that the dollars were indeed funneled into health-related expenses.

Even if donors may have limited recourse against scammers, the "platforms have an ethical obligation to protect the people using their site from fraud," says Bryanna Moore, a postdoctoral fellow at Baylor College of Medicine's Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy. "It's easy to take advantage of people who want to be charitable."

There are "different layers of deception" on a broad spectrum of fraud, ranging from "outright lying for a self-serving reason" to publicizing an imaginary illness to collect money genuinely needed for basic living expenses. With medical campaigns being a top category among crowdfunding appeals, it's "a lot of money that's exchanging hands," Moore says.

The advent of crowdfunding "reveals and, in some ways, reinforces a health care system that is totally broken," says Jessica Pierce, a faculty affiliate in the Center for Bioethics and Humanities at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in Denver. "The fact that people have to scrounge for money to get life-saving treatment is unethical."

Crowdfunding also highlights socioeconomic and racial disparities by giving an unfair advantage to those who are social-media savvy and capable of crafting a compelling narrative that attracts donors. Privacy issues enter into the picture as well, because telling that narrative entails revealing personal details, Pierce says, particularly when it comes to children, "who may not be able to consent at a really informed level."

CoFund Health, the crowdfunding site on which Anderson raised the money for his plastic surgery, offers to help people write their campaigns and copy edit for proper language, says Matthew Martin, co-founder and chief executive officer. Like other crowdfunding sites, it retains a few percent of the donations for each campaign. Martin is the husband of Anderson's acquaintance from high school.

So far, the site, which is based in Raleigh, North Carolina, has hosted about 600 crowdfunding campaigns, some completed and some still in progress. Campaigns have raised as little as $300 to cover immediate dental expenses and as much as $12,000 for cancer treatments, Martin says, but most have set a goal between $5,000 and $10,000.

Whether or not someone's campaign is based on fact or fiction remains for prospective donors to decide.

The services could be cosmetic—for example, a breast enhancement or reduction, laser procedures for the eyes or skin, and chiropractic care. A number of campaigns have sought funding for transgender surgeries, which many insurers consider optional, he says.

In July 2019, a second site was hatched out of pet owners' requests for assistance with their dogs' and cats' medical expenses. Money raised on CoFund My Pet can only be used at veterinary clinics. Martin says the debit card would be declined at other merchants, just as its CoFund Health counterpart for humans will be rejected at places other than health care facilities, dental and vision providers, and pharmacies.

Whether or not someone's campaign is based on fact or fiction remains for prospective donors to decide. If a donor were to regret a transaction, he says the site would reach out to the campaign's owner but ultimately couldn't force a refund, Martin explains, because "it's hard to chase down fraud without having access to people's health records."

In some crowdfunding campaigns, the individual needs some or all the donated resources to pay for travel and lodging at faraway destinations to receive care, says Snyder, the health sciences professor and crowdfunding report author. He suggests people only give to recipients they know personally.

"That may change the calculus a little bit," tipping the decision in favor of donating, he says. As long as the treatment isn't harmful, the funds are a small gesture of support. "There's some value in that for preserving hope or just showing them that you care."

The CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing tool could be used to "turn off" pain directly, raising ethical questions for society.

Scientists have long been aware that some people live with what's known as "congenital insensitivity to pain"—the inability to register the tingles, jolts, and aches that alert most people to injury or illness.

"If you break the chain of transmission somewhere along there, it doesn't matter what the message is—the recipient will not get it."

On the ospposite end of the spectrum, others suffer from hyperalgesia, or extreme pain; for those with erythromelalgia, also known as "Man on Fire Syndrome," warm temperatures can feel like searing heat—even wearing socks and shoes can make walking unbearable.

Strangely enough, the two conditions can be traced to mutations in the same gene, SCN9A. It produces a protein that exists in spinal cells—specifically, in the dorsal root ganglion—which transmits the sensation of pain from the nerves at the peripheral site of an injury into the central nervous system and to the brain. This fact may become the key to pain relief for the roughly 20 percent of Americans who suffer from chronic pain, and countless other patients around the world.

"If you break the chain of transmission somewhere along there, it doesn't matter what the message is—the recipient will not get it," said Dr. Fyodor Urnov, director of the Innovative Genomics Institute and a professor of molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley. "For scientists and clinicians who study this, [there's] this consistent tracking of: You break this gene, you stop feeling pain; make this gene hyperactive, you feel lots of pain—that really cuts through the correlation versus causation question."

Researchers tried for years, without much success, to find a chemical that would block that protein from working and therefore mute the pain sensation. The CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing tool could completely sidestep that approach and "turn off" pain directly.

Yet as CRISPR makes such targeted therapies increasingly possible, the ethical questions surrounding gene editing have taken on a new and more urgent cast—particularly in light of the work of the disgraced Chinese scientist He Jiankui, who announced in late 2018 that he had created the world's first genetically edited babies. He used CRISPR to edit two embryos, with the goal of disabling a gene that makes people susceptible to HIV infection; but then took the unprecedented step of implanting the edited embryos for pregnancy and birth.

Edits to germline cells, like the ones He undertook, involve alterations to gametes or embryos and carry much higher risk than somatic cell edits, since changes will be passed on to any future generations. There are also concerns that imprecise edits could result in mutations and end up causing more disorders. Recent developments, particularly the "search-and replace" prime-editing technique published last fall, will help minimize those accidental edits, but the fact remains that we have little understanding of the long-term effects of these germline edits—for the future of the patients themselves, or for the broader gene pool.

"We need to have appropriate venues where we deliberate and consider the ethical, legal and social implications of gene editing as a society."

It is much harder to predict the effects, harmful or otherwise, on the larger human population as a result of interactions with the environment or other genetic variations; with somatic cell edits, on the other hand— like the ones that would be made in an individual to turn off pain—only the person receiving the treatment is affected.

Beyond the somatic/germline distinction, there is also a larger ethical question over how much genetic interference society is willing to tolerate, which may be couched as the difference between therapeutic editing—interventions in response to a demonstrated medical need—and "enhancement" editing. The Chinese scientist He was roundly criticized in the scientific community for the fact that there are already much safer and more proven methods of preventing the parent-to-child transmission of HIV through the IVF process, making his genetic edits medically unnecessary. (The edits may also have increased the girls' risk of susceptibility to other viruses, like influenza and the West Nile virus.)

Yet there are even more extreme goals that CRISPR could be used to reach, ones further removed from any sort of medical treatment. The 1997 science fiction movie Gattaca imagined a dystopian future where genetic selection for strength and intelligence is common, creating a society that explicitly and unapologetically endorses eugenics. In the real world, Russian President Vladimir Putin has commented that genetic editing could be used to create "a genius mathematician, a brilliant musician or a soldier, a man who can fight without fear, compassion, regret or pain."

"[Such uses] would be considered using gene editing for 'enhancement,'" said Dr. Zubin Master, an associate professor of biomedical ethics at the Mayo Clinic, who noted that a series of studies have strongly suggested that members of the public, in the U.S. and around the world, are much less amenable to the prospect of gene editing for these purposes than for the treatment of illness and disease.

Putin's comments were made in 2017, before news of He's experiment broke; since then no country has moved to continue experiments on germline editing (although one Russian IVF specialist, Denis Rebrikov, appears ready to do so, if given approval). Master noted that the World Health Organization has an 18-person committee currently dedicated to considering these questions. The Expert Advisory Committee on Developing Global Standards for Governance and Oversight of Human Genome Editing first convened in March 2019; that July, it issued a recommendation to regulatory and ethics authorities in all countries to refrain from approving clinical application requests for work on human germline genome editing—the kind of alterations to genetic cells used by He. The committee's report and a fleshed-out set of guidelines is expected after its final meeting, in Geneva this September (unless the COVID-19 pandemic disrupts the timeline).

Regardless of the WHO's report, in the U.S., all regulations of new medical procedures are overseen at the federal level, subjected to extensive regulatory review by the FDA; the chance of any doctor or company going rogue is minimal to none. Likewise, the challenges we face are more on the regulatory end of the spectrum than the Gattaca end. Dr. Stephanie Malia Fullerton, a bioethics professor at the University of Washington, pointed out that eugenics not only typically involves state-sponsored control of reproduction, but requires a much more clearly delineated genetic basis of common complex traits—indeed, SCN9A is one way to get to pain, but is not the only source—and suggested that current concerns about over-prescribing opioids are a more pressing question for society to address.

In fact, Navega Therapeutics, based in San Diego, hopes to find out whether the intersection of this research into SCN9A and CRISPR would be an effective way to address the U.S. opioid crisis. Currently in a preclinical funding stage, Navega's approach focuses on editing epigenetic molecules attached to the basic DNA strand—the idea is that the gene's expression can be activated or suppressed rather than removed entirely, reducing the risk of unwanted side effects from permanently altering the genetic code.

As these studies focused on the sensation of pain go forward, what we are likely to see simultaneously is the use of CRISPR to target diseases that are the root causes of that pain. Last summer, Victoria Gray, a Mississippi woman with sickle cell disease was the second-ever person to be treated with CRISPR therapy in the U.S. The disease is caused by a genetic mutation that creates malformed blood cells, which can't carry oxygen as normal and get stuck inside blood vessels, causing debilitating pain. For the study, conducted in concert with CRISPR Therapeutics, of Cambridge, Mass., cells were removed from Gray's bone marrow, modified using CRISPR, and infused back into her body, a technique called ex vivo editing.

In early February this year, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania published a study on a first-in-human phase 1 clinical trial, in which three patients with advanced cancer received an infusion of ex vivo engineered T cells in an effort to improve antitumor immunity. The modified cells persisted for up to nine months, and the patients experienced no serious adverse side effects, suggesting that this sort of therapeutic gene editing can be performed safely and could potentially allow patients to avoid the excruciating process of chemotherapy.

Then, just this spring, researchers made another advance: The first attempt at in vivo CRISPR editing—where the edits happen inside the patient's body—is currently underway, as doctors attempt to treat a patient blinded by Leber congenital amaurosis, a rare genetic disorder. In an Oregon study sponsored by Editas Medicine and Allergan, the patient, a volunteer, was injected with a harmless virus carrying CRISPR gene-editing machinery; the hope is that the tool will be able to edit out the genetic defect and restore production of a crucial protein. Based on preliminary safety reports, the study has been cleared to continue, and data on higher doses may be available by the end of 2020. Editas Medicine and CRISPR Therapeutics are joined in this sphere by Intellia Therapeutics, which is seeking approval for a trial later this year on amyloidosis, a rare liver condition.

For any such treatment targeting SCN9A to make its way to human subjects, it would first need to undergo years' worth of testing—on mice, on primates, and then on volunteer patients after an extended informed-consent process. If everything went perfectly, Urnov estimates it could take at least three to four years end to end and cost between $5 and 10 million—but that "if" is huge.

"The idea of a regular human being, genetically pure of pain?"

And as that happens, "we need to have appropriate venues where we deliberate and consider the ethical, legal and social implications of gene editing as a society," Master said. CRISPR itself is open-source, but its application is subject to the approval of governments, institutions, and societies, which will need to figure out where to draw the line between miracle treatments and playing God. Something as unpleasant and ubiquitous as pain may in fact be the most appropriate place to start.

"The pain circuit is very old," Urnov said. "We have evolved with the senses that we have, and have become the species that we are, as a result of who we are, physiologically. Yes, I take Advil—but when I get a headache! The idea of a regular human being, genetically pure of pain?... The permanent disabling or turning down of the pain sensation, for anything other than a medical reason? … That seems to be challenging Mother Nature in the wrong ways."

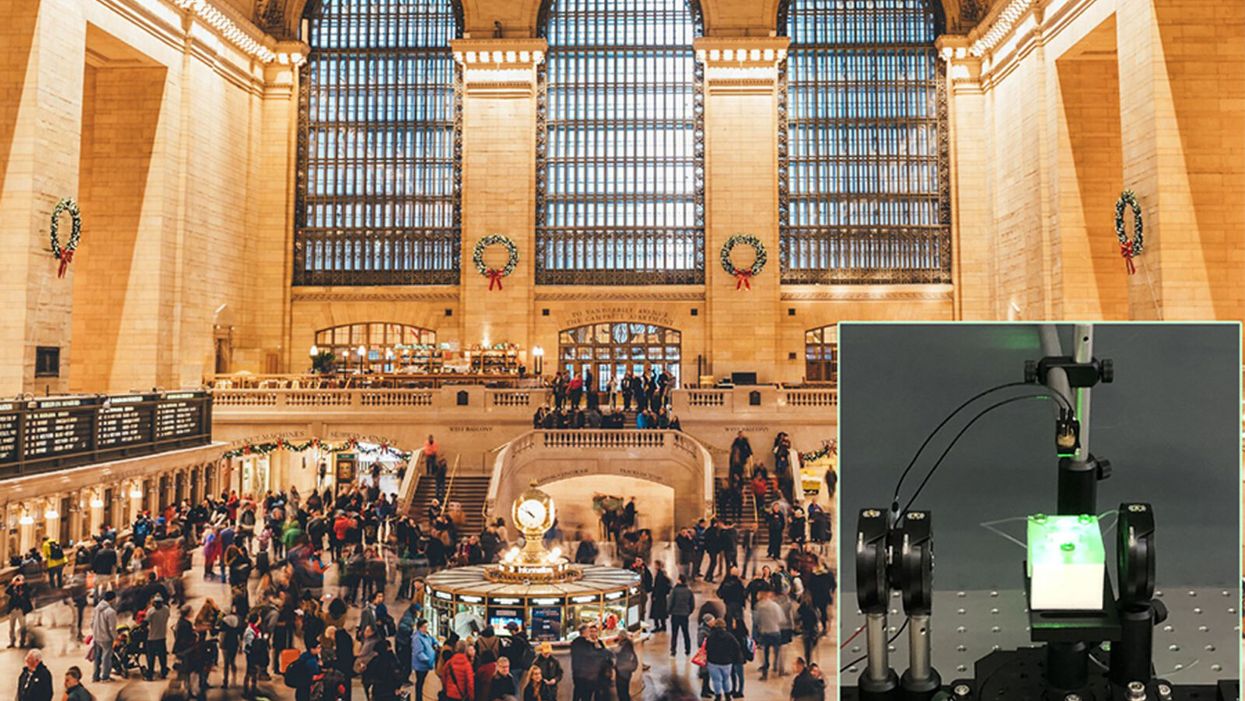

A biosensor in development (inset) could potentially be used to detect novel viruses in transit hubs like Grand Central Station in New York City.

The unprecedented scale and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has caused scientists and engineers around the world to stop whatever they were working on and shift their research toward understanding a novel virus instead.

"We have confidence that we can use our system in the next pandemic."

For Guangyu Qiu, normally an environmental engineer at the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, that means finding a clever way to take his work on detecting pollution in the air and apply it to living pathogens instead. He's developing a new type of biosensor to make disease diagnostics and detection faster and more accurate than what's currently available.

But even though this pandemic was the impetus for designing a new biosensor, Qiu actually has his eye on future disease outbreaks. He admits that it's unlikely his device will play a role in quelling this virus, but says researchers already need to be thinking about how to make better tools to fight the next one — because there will be a next one.

"In the last 20 years, there [have been] three different coronavirus [outbreaks] ... so we have to prepare for the coming one," Qiu says. "We have confidence that we can use our system in the next pandemic."

"A Really, Really Neat Idea"

His main concern is the diagnostic tool that's currently front and center for testing patients for SARS-Cov-2, the virus causing the novel coronavirus disease. The tool, called PCR (short for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction), is the gold standard because it excels at detecting viruses in even very small samples of mucus. PCR can amplify genetic material in the limited sample and look for a genetic code matching the virus in question. But in many parts of the world, mucus samples have to be sent out to laboratories for that work, and results can take days to return. PCR is also notoriously prone to false positives and negatives.

"I read a lot of newspapers that report[ed] ... a lot of false negative or false positive results at the very beginning of the outbreak," Qiu says. "It's not good for protecting people to prevent further transmission of the disease."

So he set out to build a more sensitive device—one that's less likely to give you a false result. Qiu's biosensor relies on an idea similar to the dual-factor authentication required of anyone trying to access a secure webpage. Instead of verifying that a virus is really present by using one way of detecting genetic code, as with PCR, this biosensor asks for two forms of ID.

SARS-CoV-2 is what's called an RNA virus, which means it has a single strand of genetic code, unlike double-stranded DNA. Inside Qiu's biosensor are receptors with the complementary code for this particular virus' RNA; if the virus is present, its RNA will bind with the receptors, locking together like velcro. The biosensor also contains a prism and a laser that work together to verify that this RNA really belongs to SARS-CoV-2 by looking for a specific wavelength of light and temperature.

If the biosensor doesn't detect either, or only registers a match for one and not the other, then it can't produce a positive result. This multi-step authentication process helps make sure that the RNA binding with the receptors isn't a genetically similar coronavirus like SARS-CoV, known for its 2003 outbreak, or MERS-CoV, which caused an epidemic in 2012.

It could also be fitted to detect future novel viruses once their genomes are sequenced.

The dual-feature design of this biosensor "is a really, really neat idea that I have not seen before with other sensor technology," says Erin Bromage, a professor of infection and immunology at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth; he was not involved in designing or testing Qiu's biosensor. "It makes you feel more secure that when you have a positive, you've really got a positive."

The light and temperature sensors are not in themselves new inventions, but the combination is a first. The part of the device that uses light to detect particles is actually central to Qiu's normal stream of environmental research, and is a versatile tool he's been working with for a long time to detect aerosols in the atmosphere and heavy metals in drinking water.

Bromage says this is a plus. "It's not high-risk in the sense that how they do this is unique, or not validated. They've taken aspects of really proven technology and sort of combined it together."

This new biosensor is still a prototype that will take at least another 12 months to validate in real world scenarios, though. The device is sound from a biological perspective and is sensitive enough to reliably detect SARS-CoV-2 — and to not be tricked by genetically similar viruses like SARS-CoV — but there is still a lot of engineering work that needs to be done in order for it to work outside the lab. Qiu says it's unlikely that the sensor will help minimize the impact of this pandemic, but the RNA receptors, prism, and laser inside the device can be customized to detect other viruses that may crop up in the future.

"If we choose another sequence—like SARS, like MERS, or like normal seasonal flu—we can detect other viruses, or even bacteria," Qiu says. "This device is very flexible."

It could also be fitted to detect future novel viruses once their genomes are sequenced.

The Long-Term Vision: Hospitals and Transit Hubs

The device has been designed to connect with two other systems: an air sampler and a microprocessor because the goal is to make it portable, and able to pick up samples from the air in hospitals or public areas like train stations or airports. A virus could hopefully be detected before it silently spreads and erupts into another global pandemic. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, there has been conflicting research about whether or not the virus is truly airborne (though it can be spread by droplets that briefly move through the air after a cough or sneeze), whereas the highly contagious RNA virus that causes measles can remain in the air for up to two hours.

"They've got a lot on the front end to work out," Bromage says. "They've got to work out how to capture and concentrate a virus, extract the RNA from the virus, and then get it onto the sensor. That's some pretty big hurdles, and may take some engineering that doesn't exist right now. But, if they can do that, then that works out really quite well."

One of the major obstacles in containing the COVID-19 pandemic has been in deploying accurate, quick tools that can be used for early detection of a virus outbreak and for later tracing its spread. That will still be true the next time a novel virus rears its head, and it's why Qiu feels that even if his biosensor can't help just yet, the research is still worth the effort.

It could also be fitted to detect future novel viruses once their genomes are sequenced.

The dual-feature design of this biosensor "is a really, really neat idea that I have not seen before with other sensor technology," says Erin Bromage, a professor of infection and immunology at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth; he was not involved in designing or testing Qiu's biosensor. "It makes you feel more secure that when you have a positive, you've really got a positive."

The light and temperature sensors are not in themselves new inventions, but the combination is a first. The part of the device that uses light to detect particles is actually central to Qiu's normal stream of environmental research, and is a versatile tool he's been working with for a long time to detect aerosols in the atmosphere and heavy metals in drinking water.

Bromage says this is a plus. "It's not high-risk in the sense that how they do this is unique, or not validated. They've taken aspects of really proven technology and sort of combined it together."

This new biosensor is still a prototype that will take at least another 12 months to validate in real world scenarios, though. The device is sound from a biological perspective and is sensitive enough to reliably detect SARS-CoV-2 — and to not be tricked by genetically similar viruses like SARS-CoV — but there is still a lot of engineering work that needs to be done in order for it to work outside the lab. Qiu says it's unlikely that the sensor will help minimize the impact of this pandemic, but the RNA receptors, prism, and laser inside the device can be customized to detect other viruses that may crop up in the future.

"If we choose another sequence—like SARS, like MERS, or like normal seasonal flu—we can detect other viruses, or even bacteria," Qiu says. "This device is very flexible."

It could also be fitted to detect future novel viruses once their genomes are sequenced.

The Long-Term Vision: Hospitals and Transit Hubs

The device has been designed to connect with two other systems: an air sampler and a microprocessor because the goal is to make it portable, and able to pick up samples from the air in hospitals or public areas like train stations or airports. A virus could hopefully be detected before it silently spreads and erupts into another global pandemic. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, there has been conflicting research about whether or not the virus is truly airborne (though it can be spread by droplets that briefly move through the air after a cough or sneeze), whereas the highly contagious RNA virus that causes measles can remain in the air for up to two hours.

"They've got a lot on the front end to work out," Bromage says. "They've got to work out how to capture and concentrate a virus, extract the RNA from the virus, and then get it onto the sensor. That's some pretty big hurdles, and may take some engineering that doesn't exist right now. But, if they can do that, then that works out really quite well."

One of the major obstacles in containing the COVID-19 pandemic has been in deploying accurate, quick tools that can be used for early detection of a virus outbreak and for later tracing its spread. That will still be true the next time a novel virus rears its head, and it's why Qiu feels that even if his biosensor can't help just yet, the research is still worth the effort.