As More People Crowdfund Medical Bills, Beware of Dubious Campaigns

Individuals seeking funding for experimental therapies may enroll in legitimate clinical trials -- or fall prey to snake oil.

Nearly a decade ago, Jamie Anderson hit his highest weight ever: 618 pounds. Depression drove him to eat and eat. He tried all kinds of diets, losing and regaining weight again and again. Then, four years ago, a friend nudged him to join a gym, and with a trainer's guidance, he embarked on a life-altering path.

Ethicists become particularly alarmed when medical crowdfunding appeals are for scientifically unfounded and potentially harmful interventions.

"The big catalyst for all of this is, I was diagnosed as a diabetic," says Anderson, a 46-year-old sales associate in the auto care department at Walmart. Within three years, he was down to 276 pounds but left with excess skin, which sagged from his belly to his mid-thighs.

Plastic surgery would cost $4,000 more than the sum his health insurance approved. That's when Anderson, who lives in Cabot, Arkansas, a suburb outside of Little Rock, turned to online crowdfunding to raise money. In a few months last year, current and former co-workers and friends of friends came up with that amount, covering the remaining expenses for the tummy tuck and overnight hospital stay.

The crowdfunding site that he used, CoFund Health, aimed to give his donors some peace of mind about where their money was going. Unlike GoFundMe and other platforms that don't restrict how donations are spent, Anderson's funds were loaded on a debit card that only worked at health care providers, so the donors "were assured that it was for medical bills only," he says.

CoFund Health was started in January 2019 in response to concerns about the legitimacy of many medical crowdfunding campaigns. As crowdfunding for health-related expenses has gained more traction on social media sites, with countless campaigns seeking to subsidize the high costs of care, it has given rise to some questionable transactions and legitimate ethical concerns.

Common examples of alleged fraud have involved misusing the donations for nonmedical purposes, feigning or embellishing the story of one's own unfortunate plight or that of another person, or impersonating someone else with an illness. Ethicists become particularly alarmed when medical crowdfunding appeals are for scientifically unfounded and potentially harmful interventions.

About 20 percent of American adults reported giving to a crowdfunding campaign for medical bills or treatments, according to a survey by AmeriSpeak Spotlight on Health from NORC, formerly called the National Opinion Research Center, a non-partisan research institution at the University of Chicago. The self-funded poll, conducted in November 2019, included 1,020 interviews with a representative sample of U.S. households. Researchers cited a 2019 City University of New York-Harvard study, which noted that medical bills are the most common basis for declaring personal bankruptcy.

Some experts contend that crowdfunding platforms should serve as gatekeepers in prohibiting campaigns for unproven treatments. Facing a dire diagnosis, individuals may go out on a limb to try anything and everything to prolong and improve the quality of their lives.

They may enroll in well-designed clinical trials, or they could fall prey "to snake oil being sold by people out there just making a buck," says Jeremy Snyder, a health sciences professor at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, Canada, and the lead author of a December 2019 article in The Hastings Report about crowdfunding for dubious treatments.

For instance, crowdfunding campaigns have sought donations for homeopathic healing for cancer, unapproved stem cell therapy for central nervous system injury, and extended antibiotic use for chronic Lyme disease, according to an October 2018 report in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Ford Vox, the lead author and an Atlanta-based physician specializing in brain injury, maintains that a repository should exist to monitor the outcomes of experimental treatments. "At the very least, there ought to be some tracking of what happens to the people the funds are being raised for," he says. "It would be great for an independent organization to do so."

"Even if it appears like a good cause, consumers should still do some research before donating to a crowdfunding campaign."

The Federal Trade Commission, the national consumer watchdog, cautions online that "it might be impossible for you to know if the cause is real and if the money actually gets to the intended recipient." Another caveat: Donors can't deduct contributions to individuals on tax returns.

"Even if it appears like a good cause, consumers should still do some research before donating to a crowdfunding campaign," says Malini Mithal, associate director of financial practices at the FTC. "Don't assume all medical treatments are tested and safe."

Before making any donation, it would be wise to check whether a crowdfunding site offers some sort of guarantee if a campaign ends up being fraudulent, says Kristin Judge, chief executive and founder of the Cybercrime Support Network, a Michigan-based nonprofit that serves victims before, during, and after an incident. They should know how the campaign organizer is related to the intended recipient and note whether any direct family members and friends have given funds and left supportive comments.

Donating to vetted charities offers more assurance than crowdfunding that the money will be channeled toward helping someone in need, says Daniel Billingsley, vice president of external affairs for the Oklahoma Center of Nonprofits. "Otherwise, you could be putting money into all sorts of scams." There is "zero accountability" for the crowdfunding site or the recipient to provide proof that the dollars were indeed funneled into health-related expenses.

Even if donors may have limited recourse against scammers, the "platforms have an ethical obligation to protect the people using their site from fraud," says Bryanna Moore, a postdoctoral fellow at Baylor College of Medicine's Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy. "It's easy to take advantage of people who want to be charitable."

There are "different layers of deception" on a broad spectrum of fraud, ranging from "outright lying for a self-serving reason" to publicizing an imaginary illness to collect money genuinely needed for basic living expenses. With medical campaigns being a top category among crowdfunding appeals, it's "a lot of money that's exchanging hands," Moore says.

The advent of crowdfunding "reveals and, in some ways, reinforces a health care system that is totally broken," says Jessica Pierce, a faculty affiliate in the Center for Bioethics and Humanities at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in Denver. "The fact that people have to scrounge for money to get life-saving treatment is unethical."

Crowdfunding also highlights socioeconomic and racial disparities by giving an unfair advantage to those who are social-media savvy and capable of crafting a compelling narrative that attracts donors. Privacy issues enter into the picture as well, because telling that narrative entails revealing personal details, Pierce says, particularly when it comes to children, "who may not be able to consent at a really informed level."

CoFund Health, the crowdfunding site on which Anderson raised the money for his plastic surgery, offers to help people write their campaigns and copy edit for proper language, says Matthew Martin, co-founder and chief executive officer. Like other crowdfunding sites, it retains a few percent of the donations for each campaign. Martin is the husband of Anderson's acquaintance from high school.

So far, the site, which is based in Raleigh, North Carolina, has hosted about 600 crowdfunding campaigns, some completed and some still in progress. Campaigns have raised as little as $300 to cover immediate dental expenses and as much as $12,000 for cancer treatments, Martin says, but most have set a goal between $5,000 and $10,000.

Whether or not someone's campaign is based on fact or fiction remains for prospective donors to decide.

The services could be cosmetic—for example, a breast enhancement or reduction, laser procedures for the eyes or skin, and chiropractic care. A number of campaigns have sought funding for transgender surgeries, which many insurers consider optional, he says.

In July 2019, a second site was hatched out of pet owners' requests for assistance with their dogs' and cats' medical expenses. Money raised on CoFund My Pet can only be used at veterinary clinics. Martin says the debit card would be declined at other merchants, just as its CoFund Health counterpart for humans will be rejected at places other than health care facilities, dental and vision providers, and pharmacies.

Whether or not someone's campaign is based on fact or fiction remains for prospective donors to decide. If a donor were to regret a transaction, he says the site would reach out to the campaign's owner but ultimately couldn't force a refund, Martin explains, because "it's hard to chase down fraud without having access to people's health records."

In some crowdfunding campaigns, the individual needs some or all the donated resources to pay for travel and lodging at faraway destinations to receive care, says Snyder, the health sciences professor and crowdfunding report author. He suggests people only give to recipients they know personally.

"That may change the calculus a little bit," tipping the decision in favor of donating, he says. As long as the treatment isn't harmful, the funds are a small gesture of support. "There's some value in that for preserving hope or just showing them that you care."

At the “Apple Store of Doctor’s Offices,” Preventive Care Is High Tech. Is it Worth $150 a Month?

A patient getting examined at health startup Forward.

What if going to the doctor's office could be … nice?

If you didn't have to wait for your appointment, but were ushered right in; if your medical data was all collated and easily searchable on an iPhone app; if a remote scribe took notes while you spoke with your doctor so you could make eye contact with them; if your doctor didn't seem horribly rushed.

Would you go to the doctor to get help staying healthy, rather than just to stop being sick?

Would that change the way you thought about your health? Would you go to the doctor to get help staying healthy, rather than just to stop being sick? And would that, in the long run, be much better for you?

Those are the animating questions for Forward, a healthcare startup devoted to preventive care. Led by founder Adrian Aoun, formerly of Google/Sidewalk labs, Forward opened its first office in San Francisco in 2016 and has since expanded to Los Angeles, Orange County, New York, and Washington, D.C., with a San Diego location opening soon.

It's been described as the "Apple Store of doctor's offices," which in some ways is a reaction to Forward's vibe: Patients have described the offices as having blonde wood, minimalist design, sparkling water on tap — and lots of high-tech gadgets, like the full-body scanner that replaces the standard scale and stethoscope.

The interior of a Forward office.

(Courtesy Forward)

The more crucial difference, though, is its model of care. Forward doesn't take insurance. Instead, patients, or "members," pay a flat $149 per month, along the lines of a subscription service like Netflix or a gym membership. That fee covers visits, messaging with medical staff through the Forward app, the use of a wearable (like a Fitbit or a sleep tracker) if the physician recommends it, plus any bloodwork or diagnostic tests run in the on-site labs. (The company declined to disclose how many people have signed up for memberships.)

Predictability is Forward's other significant, distinguishing feature: No surprise co-pays, or extra charges showing up on a billing statement months later. Everything is wrapped up in the $149 membership fee, unless the physician recommends visiting an outside specialist.

That caveat isn't a small one. It's important to note that Forward is in no way meant to replace standard health insurance. The service is strictly focused on preventive care, so it wouldn't be much use in case of an emergency; it's meant to help people, as far as is possible, avoid that emergency at all.

Ani Okkasian's family recently went through such an emergency. Her 62-year-old father, an active and seemingly healthy man living with diabetes, had been feeling unwell for a while, but struggled to receive constructive follow-up or tests from his doctor. It finally emerged that his liver was severely damaged, and he suffered a stroke — the risk of which can be elevated by liver disease. He seemed to deteriorate completely within mere weeks, Okkasian said, and in January he passed away.

"He was someone who'd go to the doctor regularly and listen to what they said and follow it," Okkasian said. "I shouldn't have had to bury my father at 62. I still believe to my core that his death could have been avoided if the primary care was adequate."

"I could tell that the people who designed [Forward] had lost someone to the legacy system; it was so streamlined and so much clearer."

Okkasian began researching, looking for a better alternative, and discovered Forward. Founder Aoun lost his grandfather to a heart attack; his brother's heart attack at age 31 was the impetus to start Forward.

"I could tell that that was the genesis," Okkasian said. "Having just lost someone, and having had to deal with different aspects of the healthcare industry — how complicated and convoluted that all is — I could tell that the people who designed [Forward] had lost someone to the legacy system; it was so streamlined and so much clearer."

So Who Is Forward For?

The Affordable Care Act mandates that evidence-based preventive care must be covered by insurers without any cost to the patient. Today, 30 million Americans are still living without health insurance; but for most of the population, cost shouldn't prevent access to standard, preventive care, says Benjamin Sommers, a physician and professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health who has studied the effect of the ACA on preventive care access.

For Okkasian and her family, it wasn't a lack of access to primary care that was at issue; it was the quality of that primary care. In 2019, that's probably true for a lot of people.

"How come all other industries have been disturbed except the medical industry?" Okkasian asked. "It's disturbing the most people. We're so advanced in so many ways, but when it comes to the healthcare system, we're not prioritizing the wellness of a person."

Is Forward the answer? Well, probably not for everyone. Its office are only in a handful of cities, and there are limits to how scalable it would be; it's unavoidable that the $149 per month charge restricts access for a lot of people. Those who have insurance through their employer might have a flexible spending account (FSA) that would cover some or all of the membership fee, and Forward has said that 15 percent of their early members came from underserved communities and were offered free plans; but for many others, that's just an unworkable extra cost.

Sommers also sounded a dubious note about a maximalist attitude toward data collection.

"Even though some patients may think that 'more is always better' — more testing, more screening, etc. — this isn't true," he said. "Some types of cancer screening, ovarian cancer screening for instance, are actually harmful or of no benefit, because studies have shown that they don't improve survival or health outcomes, but can lead to unnecessary testing, pain, false positives, anxiety, and other side effects.

"It's really great for people who are in good health, looking to make it better."

"I'm generally skeptical of efforts to charge people more to get 'extra testing' that isn't currently supported by the medical evidence," he added.

But relatively healthy people who want to take a more active approach to their health — or people who have frequent testing needs, like those using the HIV-prevention drug PrEP, and want to avoid co-pays — might benefit from the on-demand, low-friction experience that Forward offers.

"It's really great for people who are in good health, looking to make it better," Okkasian said. "Your experience is simplified to a point where you feel empowered, not scared."

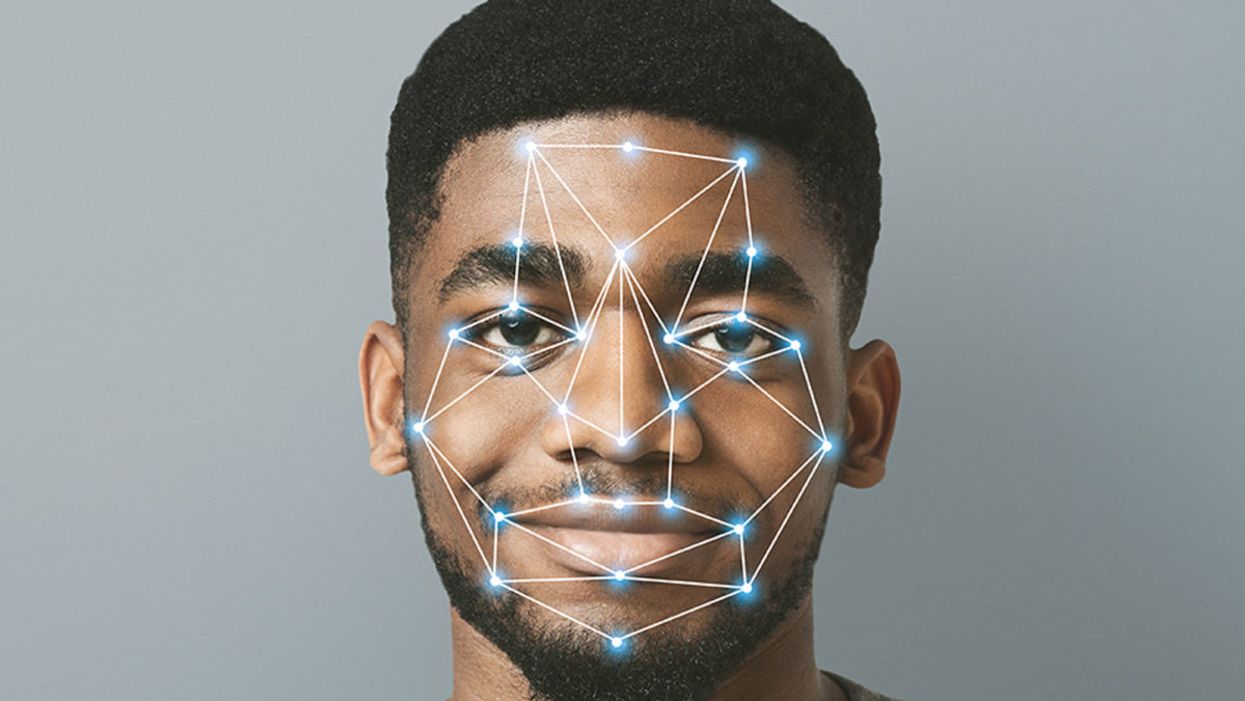

Facial Recognition Can Reduce Racial Profiling and False Arrests

The use of face recognition technology is expanding exponentially right now.

[Editor's Note: This essay is in response to our current Big Question, which we posed to experts with different perspectives: "Do you think the use of facial recognition technology by the police or government should be banned? If so, why? If not, what limits, if any, should be placed on its use?"]

Opposing facial recognition technology has become an article of faith for civil libertarians. Many who supported the bans in cities like San Francisco and Oakland have declared the technology to be inherently racist and abusive.

The greatest danger would be to categorically oppose this technology and pretend that it will simply go away.

I have spent my career as a criminal defense attorney and a civil libertarian -- and I do not fear it. Indeed, I see it as positive so long as it is appropriately regulated and controlled.

We are living in the beginning of a biometric age, where technology uses our physical or biological characteristics for a variety of products and services. It holds great promises as well as great risks. The greatest danger, however, would be to categorically oppose this technology and pretend that it will simply go away.

This is an age driven as much by consumer as it is government demand. Living in denial may be emotionally appealing, but it will only hasten the creation of post-privacy world. If we do not address this emerging technology, movements in public will increasingly result in instant recognition and even tracking. It is the type of fish-bowl society that strips away any expectation of privacy in our interactions and associations.

The biometrics field is expanding exponentially, largely due to the popularity of consumer products using facial recognition technology (FRT) -- from the iPhone program to shopping ones that recognize customers.

But the privacy community is losing this battle because it is using the privacy rationales and doctrines forged in the earlier electronic surveillance periods. Just as generals are often accused of planning to fight the last war, civil libertarians can sometimes cling to past models despite their decreasing relevance in the current world.

I see FRT as having positive implications that are worth pursuing. When properly used, biometrics can actually enhance privacy interests and even reduce racial profiling by reducing false arrests and the warrantless "patdowns" allowed by the Supreme Court. Bans not only deny police a technology widely used by businesses, but return police to the highly flawed default of "eye balling" suspects -- a system with a considerably higher error rate than top FRT programs.

Officers are often wrong and stop a great number of suspects in the hopes of finding a wanted felon.

A study in Australia showed that passport officers who had taken photographs of subjects in ideal conditions nonetheless experienced high error rates when identifying them shortly afterward, including 14 percent false acceptance rates. Currently, officers stop suspects based on their memory from seeing a photograph days or weeks earlier. They are often wrong and stop a great number of suspects in the hopes of finding a wanted felon. The best FRT programs achieve an astonishing accuracy rate, though real-world implementation has challenges that must be addressed.

One legitimate concern raised in early studies showed higher error rates in recognitions for certain groups, particularly African American women. An MIT study finding that error rate prompted major improvements in the algorithms as well as training changes to greatly reduce the frequency of errors. The issue remains a concern, but there is nothing inherently racist in algorithms. These are a set of computer instructions that isolate and process with the parameters and conditions set by creators.

To be sure, there is room for improvement in some algorithms. Tests performed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) reportedly showed only an 80 percent accuracy rate in comparing mug shots to pictures of members of Congress when using Amazon's "Rekognition" system. It recently showed the same 80 percent rate in doing the same comparison to members of the California legislators.

However, different algorithms are available with differing levels of performance. Moreover, these products can be set with a lower discrimination level. The fact is that the top algorithms tested by the National Institute of Standards and Technology showed that their accuracy rate is greater than 99 percent.

The greatest threat of biometric technologies is to democratic values.

Assuming a top-performing algorithm is used, the result could be highly beneficial for civil liberties as opposed to the alternative of "eye balling" suspects. Consider the Boston Bombing where police declared a "containment zone" and forced families into the street with their hands in the air.

The suspect, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, moved around Boston and was ultimately found outside the "containment zone" once authorities abandoned near martial law. He was caught on some surveillance systems but not identified. FRT can help law enforcement avoid time-consuming area searches and the questionable practice of forcing people out of their homes to physically examine them.

If we are to avoid a post-privacy world, we will have to redefine what we are trying to protect and reconceive how we hope to protect it. In my view, the greatest threat of biometric technologies is to democratic values. Authoritarian nations like China have made huge investments into FRT precisely because they know that the threat of recognition in public deters citizens from associating or interacting with protesters or dissidents. Recognition changes conduct. That chilling effect is what we have the worry about the most.

Conventional privacy doctrines do not offer much protection. The very concept of "public privacy" is treated as something of an oxymoron by courts. Public acts and associations are treated as lacking any reasonable expectation of privacy. In the same vein, the right to anonymity is not a strong avenue for protection. We are not living in an anonymous world anymore.

Consumers want products like FaceFind, which link their images with others across social media. They like "frictionless" transactions and authentications using faceprints. Despite the hyperbole in places like San Francisco, civil libertarians will not succeed in getting that cat to walk backwards.

The basis for biometric privacy protection should not be focused on anonymity, but rather obscurity. You will be increasingly subject to transparency-forcing technology, but we can legislatively mandate ways of obscuring that information. That is the objective of the Biometric Privacy Act that I have proposed in recent research. However, no such comprehensive legislation has passed through Congress.

The ability to spot fraudulent entries at airports or recognizing a felon in flight has obvious benefits for all citizens.

We also need to recognize that FRT has many beneficial uses. Biometric guns can reduce accidents and criminals' conduct. New authentications using FRT and other biometric programs could reduce identity theft.

And, yes, FRT could help protect against unnecessary police stops or false arrests. Finally, and not insignificantly, this technology could stop serious crimes, from terrorist attacks to the capturing of dangerous felons. The ability to spot fraudulent entries at airports or recognizing a felon in flight has obvious benefits for all citizens.

We can live and thrive in a biometric era. However, we will need to bring together civil libertarians with business and government experts if we are going to control this technology rather than have it control us.

[Editor's Note: Read the opposite perspective here.]