Big Data Probably Knows More About You Than Your Friends Do

A representation of the digital lifestyle prevalent today that enables the collection of a wealth of data.

Data is the new oil. It is highly valuable, and it is everywhere, even if you're not aware of it. For example, it's there when you use social media. Sharing pictures on Facebook lets its facial recognition software peg you and your friends. Thanks to that software, now anywhere you visit that has installed cameras, your face can be identified and your actions recorded.

The big data revolution is advancing much faster than the ones before, and it carries both promises and perils for humanity.

It's there when you log into Twitter, posting one of the 230 million tweets per day, which up until last month were all archived by the Library of Congress and will be made public for research. These social media data can be used to predict your political affiliations, ethnicity, race, age, how close you are with your family and friends, your mental health, even when you are most likely to be grumpy or go to the gym. These data can also predict when you are apt to get sick and track how diseases are spreading.

In fact, tracking isn't limited to what you decide to share or public spaces anymore. Lab experiments show Comcast and other cable companies may soon be able to record and monitor movements in your house. They may also be able to read your lips and identify your visitors simply by assessing how Wi-Fi waves bounce off bodies and other objects in houses. In one study, MIT researchers used routers and sensors to monitor breathing and heart rates with 99% accuracy. Routers could soon be used for seemingly good things, like monitoring infant breathing and whether an older adult is about to take a big tumble. However, it may also enable unwanted and unparalleled levels of surveillance.

Some call the first digital pill a snitch pill, medication with a tattletale, and big brother in your belly.

Big data is there every time you pick up your smartphone, which can track your daily steps, where you go via geolocation, what time you wake up and go to bed, your punctuality, and even your overall health depending on which features you have enabled. Are you close with your mom; are you a sedentary couch potato; did you commit a murder (iPhone data was recently used in a German murder trial)? Smartphone-generated data can be used to label you---and not just you, your future and past generations too.

Smartphones are not the only "things" gathering data on you. Anything with an on and off switch can be connected to the internet and generate data. The new rule seems to be, if it can be, it will be, connected. Washing machines, coffee makers, medical appliances, cars, and even your luggage (yes, someone created a self-driving suitcase) can and are often generating data. "Smart" refrigerators can monitor your food levels and automatically create shopping lists and order food for you—while recording your alcohol consumption and whether you tend to be a healthy or junk food eater.

Even medicines can monitor behaviors. The first digital pill was just approved by the FDA last November to track whether patients take their medicines. It has a sensor that sends signals to a patient's smartphone, and others, when it encounters stomach acid. Some call it a snitch pill, medication with a tattletale, and big brother in your belly. Others see it as a major breakthrough to help patients remember to take their medications and to save payers millions of dollars.

Big data is there when you go shopping. Credit card and retail data can show whether you pay for a gym, if you are pregnant, have children, and your credit-worthiness. Uber and Lyft transactional data reveal what time you usually go to and leave work and who you regularly visit (Uber data has been used to catch cheating spouses).

Amazon now sells a bedroom camera to see your fashion choices and offer advice. It is marketing a more fashionable you, but it probably also wants the video feed showing your body measurements—they're "a newly prized currency," according to the Washington Post. They help retailers create more customized and better fitting clothes. Amazon also just partnered with Berkshire Hathaway and JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank in the United States by assets, to create an independent health-care company for their employees--raising privacy concerns as Amazon already owns so much data about us, from drones, devices, the AI of Alexa, and our viewing, eating, and other purchasing habits on Amazon Prime.

Data generation and storage can also be used to make the world better, safer and fairer.

Big data is arguably a new phenomenon; almost all the world's data (90%) were produced within the last 2 years or so. It is a result of the fusion of physical, digital, and biological technologies that together constitute the fourth industrial revolution, according to the World Economic Forum. Unlike the last three revolutions, involving the discoveries of steam power, electrical energy, and computers—this revolution is advancing much faster than the ones before and it carries both promises and perils for humanity.

Some people may want to opt out of all this tracking, reduce their digital footprint and stay "off the grid." However, it is worth noting that data generation and storage can be used for great things --- things that make the world better, safer and fairer. For example, sharing electronic health records and social media data can help scientists better track and understand diseases, develop new cures and therapies, and understand the safety and efficacy profiles of medicines and vaccines.

While full of promise, big data is not without its pitfalls. Data are often not interoperable or easily integrated. You can use your credit card practically anywhere in the world, but you cannot easily port your electronic health record to the doctor or hospital across the street, for example.

Data quality can also be poor. It is dependent on the person entering it. My electronic health record at one point said I was male, and I was pregnant at the time. No doctors or nurses seemed to notice. The problem is worse on a global level. For example, causes of death can be coded differently by country and village. Take HIV patients: they often develop secondary infections, like TB. Do you record the cause of death as TB or HIV? There isn't global consistency, and political pressure from patient groups can exert itself on death records. Often, each group wants to say they have the most deaths so they can fundraise more money.

Data can be biased. More than 80 percent of genomic data comes from Caucasians. Only 14 percent is from Asians and 3.5 percent is from African and Hispanic populations. Thus, when scientists use genomic data to develop drugs or lab tests, they may create biased products that work for only some demographics. Take type 2 diabetes blood tests; some do not work well for African Americans. One study estimates that 650,000 African Americans may have undiagnosed diabetes, because a common blood test doesn't work for them. Using biased data in medicine can be a matter of life and death. Moreover, if genomic medicine benefits only "a privileged few," the practice raises concerns about unequal access.

Large companies are selling data that originated from you and you are not sharing in the wealth.

We need to think carefully and be transparent about the values embedded in our data, data analytics (algorithms), and data applications. Numbers are never neutral. Algorithms are always embedded with subjective normative values--sometimes purposely, sometimes not. To address this problem, we need ethicists who can audit databanks and algorithms to identify embedded norms, values and biases and help ensure they are addressed or at least transparently disclosed. Additionally, we need to determine how to let people opt out of certain types of data collection and uses—and not just at the beginning of a system, but also at any point in their lifetimes. There is a right to be forgotten, which hasn't been adequately operationalized in today's data sphere.

What do you think happens to all of these data collected about us? The short answer is the public doesn't really know. A lot of it looks like what is in a medical record—i.e. height, weight, pregnancy status, age, mental health, pulse, blood pressure, and illness symptoms--- yet, it isn't protected by HIPPA, like your medical record information.

And it is being consolidated into the hands of fewer and fewer big players. Large companies are selling data that originated from you and you are not sharing in the wealth.

A possible solution is to create an app, managed by a nonprofit or public benefit corporation, through which you could download and manage all the data collected about you. For example, you could download your credit card statements with all your purchasing habits, your Uber rides showing transit patterns, medical records, electric bills, every digital record you have and would like to download--into one application. You would then have the power to license pieces or the collection of your data to users for a small fee for one year at a time. Uses and users could be monitored and audited leveraging blockchain capabilities. After the year is up, you can withdraw access.

You could be your own data landlord. We could democratize big data and empower people to better control and manage the wealth of information collected about us. Why should only the big companies like Amazon and Apple profit off the new oil? Let's create an app so we can all manage our data wealth and maybe even become data barons—an app created by the people for the people.

A movie still from the 1966 film "Fantastic Voyage"

In the 1966 movie "Fantastic Voyage," actress Raquel Welch and her submarine were shrunk to the size of a cell in order to eliminate a blood clot in a scientist's brain. Now, 55 years later, the scenario is becoming closer to reality.

California-based startup Bionaut Labs has developed a nanobot about the size of a grain of rice that's designed to transport medication to the exact location in the body where it's needed. If you think about it, the conventional way to deliver medicine makes little sense: A painkiller affects the entire body instead of just the arm that's hurting, and chemotherapy is flushed through all the veins instead of precisely targeting the tumor.

"Chemotherapy is delivered systemically," Bionaut-founder and CEO Michael Shpigelmacher says. "Often only a small percentage arrives at the location where it is actually needed."

But what if it was possible to send a tiny robot through the body to attack a tumor or deliver a drug at exactly the right location?

Several startups and academic institutes worldwide are working to develop such a solution but Bionaut Labs seems the furthest along in advancing its invention. "You can think of the Bionaut as a tiny screw that moves through the veins as if steered by an invisible screwdriver until it arrives at the tumor," Shpigelmacher explains. Via Zoom, he shares the screen of an X-ray machine in his Culver City lab to demonstrate how the half-transparent, yellowish device winds its way along the spine in the body. The nanobot contains a tiny but powerful magnet. The "invisible screwdriver" is an external magnetic field that rotates that magnet inside the device and gets it to move and change directions.

The current model has a diameter of less than a millimeter. Shpigelmacher's engineers could build the miniature vehicle even smaller but the current size has the advantage of being big enough to see with bare eyes. It can also deliver more medicine than a tinier version. In the Zoom demonstration, the micorobot is injected into the spine, not unlike an epidural, and pulled along the spine through an outside magnet until the Bionaut reaches the brainstem. Depending which organ it needs to reach, it could be inserted elsewhere, for instance through a catheter.

"The hope is that we can develop a vehicle to transport medication deep into the body," says Max Planck scientist Tian Qiu.

Imagine moving a screw through a steak with a magnet — that's essentially how the device works. But of course, the Bionaut is considerably different from an ordinary screw: "At the right location, we give a magnetic signal, and it unloads its medicine package," Shpigelmacher says.

To start, Bionaut Labs wants to use its device to treat Parkinson's disease and brain stem gliomas, a type of cancer that largely affects children and teenagers. About 300 to 400 young people a year are diagnosed with this type of tumor. Radiation and brain surgery risk damaging sensitive brain tissue, and chemotherapy often doesn't work. Most children with these tumors live less than 18 months. A nanobot delivering targeted chemotherapy could be a gamechanger. "These patients really don't have any other hope," Shpigelmacher says.

Of course, the main challenge of the developing such a device is guaranteeing that it's safe. Because tissue is so sensitive, any mistake could risk disastrous results. In recent years, Bionaut has tested its technology in dozens of healthy sheep and pigs with no major adverse effects. Sheep make a good stand-in for humans because their brains and spines are similar to ours.

The Bionaut device is about the size of a grain of rice.

Bionaut Labs

"As the Bionaut moves through brain tissue, it creates a transient track that heals within a few weeks," Shpigelmacher says. The company is hoping to be the first to test a nanobot in humans. In December 2022, it announced that a recent round of funding drew $43.2 million, for a total of 63.2 million, enabling more research and, if all goes smoothly, human clinical trials by early next year.

Once the technique has been perfected, further applications could include addressing other kinds of brain disorders that are considered incurable now, such as Alzheimer's or Huntington's disease. "Microrobots could serve as a bridgehead, opening the gateway to the brain and facilitating precise access of deep brain structure – either to deliver medication, take cell samples or stimulate specific brain regions," Shpigelmacher says.

Robot-assisted hybrid surgery with artificial intelligence is already used in state-of-the-art surgery centers, and many medical experts believe that nanorobotics will be the instrument of the future. In 2016, three scientists were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their development of "the world's smallest machines," nano "elevators" and minuscule motors. Since then, the scientific experiments have progressed to the point where applicable devices are moving closer to actually being implemented.

Bionaut's technology was initially developed by a research team lead by Peer Fischer, head of the independent Micro Nano and Molecular Systems Lab at the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart, Germany. Fischer is considered a pioneer in the research of nano systems, which he began at Harvard University more than a decade ago. He and his team are advising Bionaut Labs and have licensed their technology to the company.

"The hope is that we can develop a vehicle to transport medication deep into the body," says Max Planck scientist Tian Qiu, who leads the cooperation with Bionaut Labs. He agrees with Shpigelmacher that the Bionaut's size is perfect for transporting medication loads and is researching potential applications for even smaller nanorobots, especially in the eye, where the tissue is extremely sensitive. "Nanorobots can sneak through very fine tissue without causing damage."

In "Fantastic Voyage," Raquel Welch's adventures inside the body of a dissident scientist let her swim through his veins into his brain, but her shrunken miniature submarine is attacked by antibodies; she has to flee through the nerves into the scientist's eye where she escapes into freedom on a tear drop. In reality, the exit in the lab is much more mundane. The Bionaut simply leaves the body through the same port where it entered. But apart from the dramatization, the "Fantastic Voyage" was almost prophetic, or, as Shpigelmacher says, "Science fiction becomes science reality."

This article was first published by Leaps.org on April 12, 2021.

How the Human Brain Project Built a Mind of its Own

In 2013, the Human Brain Project set out to build a realistic computer model of the brain over ten years. Now, experts are reflecting on HBP's achievements with an eye toward the future.

In 2009, neuroscientist Henry Markram gave an ambitious TED talk. “Our mission is to build a detailed, realistic computer model of the human brain,” he said, naming three reasons for this unmatched feat of engineering. One was because understanding the human brain was essential to get along in society. Another was because experimenting on animal brains could only get scientists so far in understanding the human ones. Third, medicines for mental disorders weren’t good enough. “There are two billion people on the planet that are affected by mental disorders, and the drugs that are used today are largely empirical,” Markram said. “I think that we can come up with very concrete solutions on how to treat disorders.”

Markram's arguments were very persuasive. In 2013, the European Commission launched the Human Brain Project, or HBP, as part of its Future and Emerging Technologies program. Viewed as Europe’s chance to try to win the “brain race” between the U.S., China, Japan, and other countries, the project received about a billion euros in funding with the goal to simulate the entire human brain on a supercomputer, or in silico, by 2023.

Now, after 10 years of dedicated neuroscience research, the HBP is coming to an end. As its many critics warned, it did not manage to build an entire human brain in silico. Instead, it achieved a multifaceted array of different goals, some of them unexpected.

Scholars have found that the project did help advance neuroscience more than some detractors initially expected, specifically in the area of brain simulations and virtual models. Using an interdisciplinary approach of combining technology, such as AI and digital simulations, with neuroscience, the HBP worked to gain a deeper understanding of the human brain’s complicated structure and functions, which in some cases led to novel treatments for brain disorders. Lastly, through online platforms, the HBP spearheaded a previously unmatched level of global neuroscience collaborations.

Simulating a human brain stirs up controversy

Right from the start, the project was plagued with controversy and condemnation. One of its prominent critics was Yves Fregnac, a professor in cognitive science at the Polytechnic Institute of Paris and research director at the French National Centre for Scientific Research. Fregnac argued in numerous articles that the HBP was overfunded based on proposals with unrealistic goals. “This new way of over-selling scientific targets, deeply aligned with what modern society expects from mega-sciences in the broad sense (big investment, big return), has been observed on several occasions in different scientific sub-fields,” he wrote in one of his articles, “before invading the field of brain sciences and neuromarketing.”

"A human brain model can simulate an experiment a million times for many different conditions, but the actual human experiment can be performed only once or a few times," said Viktor Jirsa, a professor at Aix-Marseille University.

Responding to such critiques, the HBP worked to restructure the effort in its early days with new leadership, organization, and goals that were more flexible and attainable. “The HBP got a more versatile, pluralistic approach,” said Viktor Jirsa, a professor at Aix-Marseille University and one of the HBP lead scientists. He believes that these changes fixed at least some of HBP’s issues. “The project has been on a very productive and scientifically fruitful course since then.”

After restructuring, the HBP became a European hub on brain research, with hundreds of scientists joining its growing network. The HBP created projects focused on various brain topics, from consciousness to neurodegenerative diseases. HBP scientists worked on complex subjects, such as mapping out the brain, combining neuroscience and robotics, and experimenting with neuromorphic computing, a computational technique inspired by the human brain structure and function—to name just a few.

Simulations advance knowledge and treatment options

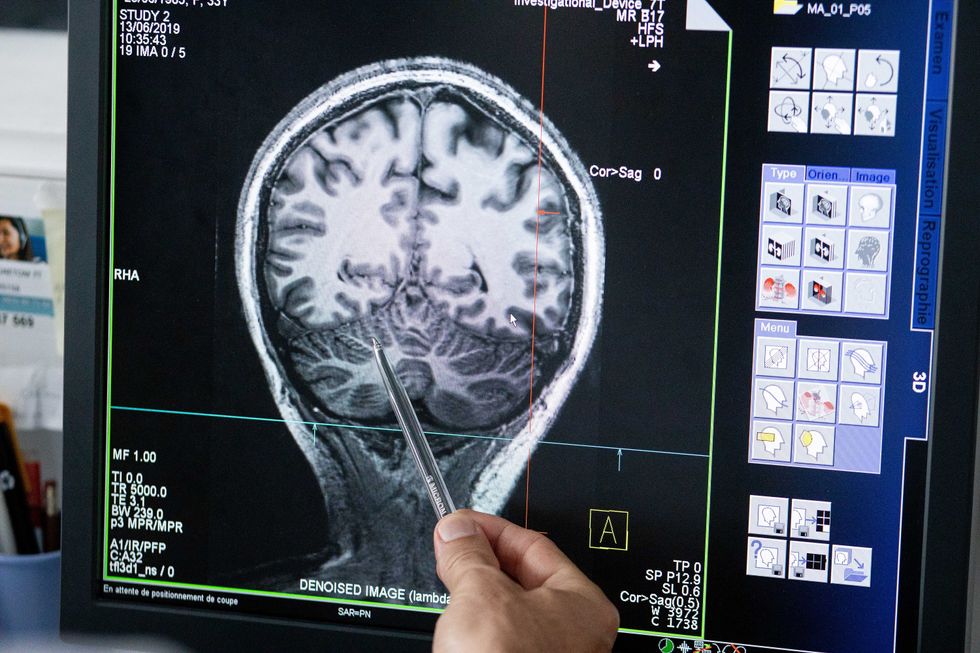

In 2013, it seemed that bringing neuroscience into a digital age would be farfetched, but research within the HBP has made this achievable. The virtual maps and simulations various HBP teams create through brain imaging data make it easier for neuroscientists to understand brain developments and functions. The teams publish these models on the HBP’s EBRAINS online platform—one of the first to offer access to such data to neuroscientists worldwide via an open-source online site. “This digital infrastructure is backed by high-performance computers, with large datasets and various computational tools,” said Lucy Xiaolu Wang, an assistant professor in the Resource Economics Department at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, who studies the economics of the HBP. That means it can be used in place of many different types of human experimentation.

Jirsa’s team is one of many within the project that works on virtual brain models and brain simulations. Compiling patient data, Jirsa and his team can create digital simulations of different brain activities—and repeat these experiments many times, which isn’t often possible in surgeries on real brains. “A human brain model can simulate an experiment a million times for many different conditions,” Jirsa explained, “but the actual human experiment can be performed only once or a few times.” Using simulations also saves scientists and doctors time and money when looking at ways to diagnose and treat patients with brain disorders.

Compiling patient data, scientists can create digital simulations of different brain activities—and repeat these experiments many times.

The Human Brain Project

Simulations can help scientists get a full picture that otherwise is unattainable. “Another benefit is data completion,” added Jirsa, “in which incomplete data can be complemented by the model. In clinical settings, we can often measure only certain brain areas, but when linked to the brain model, we can enlarge the range of accessible brain regions and make better diagnostic predictions.”

With time, Jirsa’s team was able to move into patient-specific simulations. “We advanced from generic brain models to the ability to use a specific patient’s brain data, from measurements like MRI and others, to create individualized predictive models and simulations,” Jirsa explained. He and his team are working on this personalization technique to treat patients with epilepsy. According to the World Health Organization, about 50 million people worldwide suffer from epilepsy, a disorder that causes recurring seizures. While some epilepsy causes are known others remain an enigma, and many are hard to treat. For some patients whose epilepsy doesn’t respond to medications, removing part of the brain where seizures occur may be the only option. Understanding where in the patients’ brains seizures arise can give scientists a better idea of how to treat them and whether to use surgery versus medications.

“We apply such personalized models…to precisely identify where in a patient’s brain seizures emerge,” Jirsa explained. “This guides individual surgery decisions for patients for which surgery is the only treatment option.” He credits the HBP for the opportunity to develop this novel approach. “The personalization of our epilepsy models was only made possible by the Human Brain Project, in which all the necessary tools have been developed. Without the HBP, the technology would not be in clinical trials today.”

Personalized simulations can significantly advance treatments, predict the outcome of specific medical procedures and optimize them before actually treating patients. Jirsa is watching this happen firsthand in his ongoing research. “Our technology for creating personalized brain models is now used in a large clinical trial for epilepsy, funded by the French state, where we collaborate with clinicians in hospitals,” he explained. “We have also founded a spinoff company called VB Tech (Virtual Brain Technologies) to commercialize our personalized brain model technology and make it available to all patients.”

The Human Brain Project created a level of interconnectedness within the neuroscience research community that never existed before—a network not unlike the brain’s own.

Other experts believe it’s too soon to tell whether brain simulations could change epilepsy treatments. “The life cycle of developing treatments applicable to patients often runs over a decade,” Wang stated. “It is still too early to draw a clear link between HBP’s various project areas with patient care.” However, she admits that some studies built on the HBP-collected knowledge are already showing promise. “Researchers have used neuroscientific atlases and computational tools to develop activity-specific stimulation programs that enabled paraplegic patients to move again in a small-size clinical trial,” Wang said. Another intriguing study looked at simulations of Alzheimer’s in the brain to understand how it evolves over time.

Some challenges remain hard to overcome even with computer simulations. “The major challenge has always been the parameter explosion, which means that many different model parameters can lead to the same result,” Jirsa explained. An example of this parameter explosion could be two different types of neurodegenerative conditions, such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases. Both afflict the same area of the brain, the basal ganglia, which can affect movement, but are caused by two different underlying mechanisms. “We face the same situation in the living brain, in which a large range of diverse mechanisms can produce the same behavior,” Jirsa said. The simulations still have to overcome the same challenge.

Understanding where in the patients’ brains seizures arise can give scientists a better idea of how to treat them and whether to use surgery versus medications.

The Human Brain Project

A network not unlike the brain’s own

Though the HBP will be closing this year, its legacy continues in various studies, spin-off companies, and its online platform, EBRAINS. “The HBP is one of the earliest brain initiatives in the world, and the 10-year long-term goal has united many researchers to collaborate on brain sciences with advanced computational tools,” Wang said. “Beyond the many research articles and projects collaborated on during the HBP, the online neuroscience research infrastructure EBRAINS will be left as a legacy even after the project ends.”

Those who worked within the HBP see the end of this project as the next step in neuroscience research. “Neuroscience has come closer to very meaningful applications through the systematic link with new digital technologies and collaborative work,” Jirsa stated. “In that way, the project really had a pioneering role.” It also created a level of interconnectedness within the neuroscience research community that never existed before—a network not unlike the brain’s own. “Interconnectedness is an important advance and prerequisite for progress,” Jirsa said. “The neuroscience community has in the past been rather fragmented and this has dramatically changed in recent years thanks to the Human Brain Project.”

According to its website, by 2023 HBP’s network counted over 500 scientists from over 123 institutions and 16 different countries, creating one of the largest multi-national research groups in the world. Even though the project hasn’t produced the in-silico brain as Markram envisioned it, the HBP created a communal mind with immense potential. “It has challenged us to think beyond the boundaries of our own laboratories,” Jirsa said, “and enabled us to go much further together than we could have ever conceived going by ourselves.”