Can blockchain help solve the Henrietta Lacks problem?

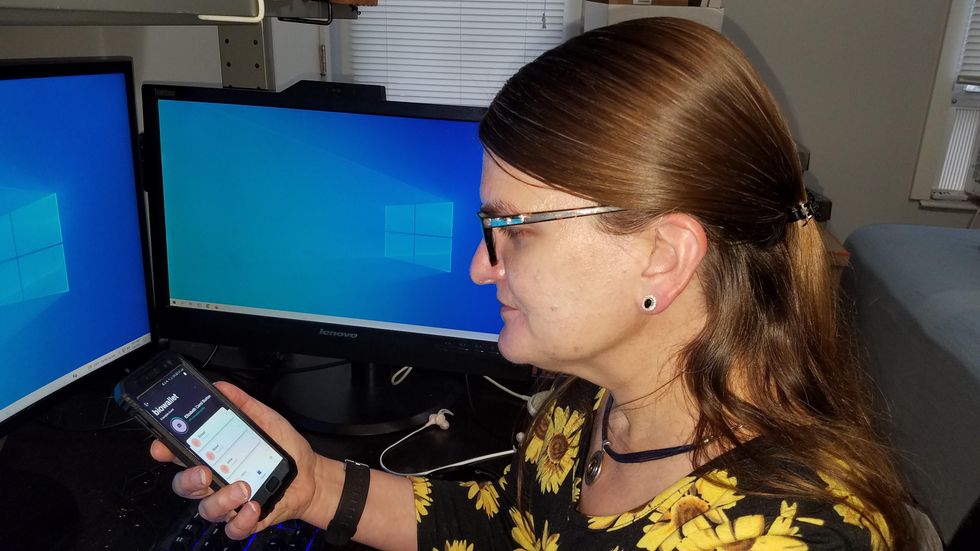

Marielle Gross, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, shows patients a new app that tracks how their samples are used during biomedical research.

Science has come a long way since Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman from Baltimore, succumbed to cervical cancer at age 31 in 1951 -- only eight months after her diagnosis. Since then, research involving her cancer cells has advanced scientific understanding of the human papilloma virus, polio vaccines, medications for HIV/AIDS and in vitro fertilization.

Today, the World Health Organization reports that those cells are essential in mounting a COVID-19 response. But they were commercialized without the awareness or permission of Lacks or her family, who have filed a lawsuit against a biotech company for profiting from these “HeLa” cells.

While obtaining an individual's informed consent has become standard procedure before the use of tissues in medical research, many patients still don’t know what happens to their samples. Now, a new phone-based app is aiming to change that.

Tissue donors can track what scientists do with their samples while safeguarding privacy, through a pilot program initiated in October by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics and the University of Pittsburgh’s Institute for Precision Medicine. The program uses blockchain technology to offer patients this opportunity through the University of Pittsburgh's Breast Disease Research Repository, while assuring that their identities remain anonymous to investigators.

A blockchain is a digital, tamper-proof ledger of transactions duplicated and distributed across a computer system network. Whenever a transaction occurs with a patient’s sample, multiple stakeholders can track it while the owner’s identity remains encrypted. Special certificates called “nonfungible tokens,” or NFTs, represent patients’ unique samples on a trusted and widely used blockchain that reinforces transparency.

Blockchain could be used to notify people if cancer researchers discover that they have certain risk factors.

“Healthcare is very data rich, but control of that data often does not lie with the patient,” said Julius Bogdan, vice president of analytics for North America at the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS), a Chicago-based global technology nonprofit. “NFTs allow for the encapsulation of a patient’s data in a digital asset controlled by the patient.” He added that this technology enables a more secure and informed method of participating in clinical and research trials.

Without this technology, de-identification of patients’ samples during biomedical research had the unintended consequence of preventing them from discovering what researchers find -- even if that data could benefit their health. A solution was urgently needed, said Marielle Gross, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive science and bioethics at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

“A researcher can learn something from your bio samples or medical records that could be life-saving information for you, and they have no way to let you or your doctor know,” said Gross, who is also an affiliate assistant professor at the Berman Institute. “There’s no good reason for that to stay the way that it is.”

For instance, blockchain could be used to notify people if cancer researchers discover that they have certain risk factors. Gross estimated that less than half of breast cancer patients are tested for mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 — tumor suppressor genes that are important in combating cancer. With normal function, these genes help prevent breast, ovarian and other cells from proliferating in an uncontrolled manner. If researchers find mutations, it’s relevant for a patient’s and family’s follow-up care — and that’s a prime example of how this newly designed app could play a life-saving role, she said.

Liz Burton was one of the first patients at the University of Pittsburgh to opt for the app -- called de-bi, which is short for decentralized biobank -- before undergoing a mastectomy for early-stage breast cancer in November, after it was diagnosed on a routine mammogram. She often takes part in medical research and looks forward to tracking her tissues.

“Anytime there’s a scientific experiment or study, I’m quick to participate -- to advance my own wellness as well as knowledge in general,” said Burton, 49, a life insurance service representative who lives in Carnegie, Pa. “It’s my way of contributing.”

Liz Burton was one of the first patients at the University of Pittsburgh to opt for the app before undergoing a mastectomy for early-stage breast cancer.

Liz Burton

The pilot program raises the issue of what investigators may owe study participants, especially since certain populations, such as Black and indigenous peoples, historically were not treated in an ethical manner for scientific purposes. “It’s a truly laudable effort,” Tamar Schiff, a postdoctoral fellow in medical ethics at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine, said of the endeavor. “Research participants are beautifully altruistic.”

Lauren Sankary, a bioethicist and associate director of the neuroethics program at Cleveland Clinic, agrees that the pilot program provides increased transparency for study participants regarding how scientists use their tissues while acknowledging individuals’ contributions to research.

However, she added, “it may require researchers to develop a process for ongoing communication to be responsive to additional input from research participants.”

Peter H. Schwartz, professor of medicine and director of Indiana University’s Center for Bioethics in Indianapolis, said the program is promising, but he wonders what will happen if a patient has concerns about a particular research project involving their tissues.

“I can imagine a situation where a patient objects to their sample being used for some disease they’ve never heard about, or which carries some kind of stigma like a mental illness,” Schwartz said, noting that researchers would have to evaluate how to react. “There’s no simple answer to those questions, but the technology has to be assessed with an eye to the problems it could raise.”

To truly make a difference, blockchain must enable broad consent from patients, not just de-identification.

As a result, researchers may need to factor in how much information to share with patients and how to explain it, Schiff said. There are also concerns that in tracking their samples, patients could tell others what they learned before researchers are ready to publicly release this information. However, Bogdan, the vice president of the HIMSS nonprofit, believes only a minimal study identifier would be stored in an NFT, not patient data, research results or any type of proprietary trial information.

Some patients may be confused by blockchain and reluctant to embrace it. “The complexity of NFTs may prevent the average citizen from capitalizing on their potential or vendors willing to participate in the blockchain network,” Bogdan said. “Blockchain technology is also quite costly in terms of computational power and energy consumption, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.”

In addition, this nascent, groundbreaking technology is immature and vulnerable to data security flaws, disputes over intellectual property rights and privacy issues, though it does offer baseline protections to maintain confidentiality. To truly make a difference, blockchain must enable broad consent from patients, not just de-identification, said Robyn Shapiro, a bioethicist and founding attorney at Health Sciences Law Group near Milwaukee.

The Henrietta Lacks story is a prime example, Shapiro noted. During her treatment for cervical cancer at Johns Hopkins, Lacks’s tissue was de-identified (albeit not entirely, because her cell line, HeLa, bore her initials). After her death, those cells were replicated and distributed for important and lucrative research and product development purposes without her knowledge or consent.

Nonetheless, Shapiro thinks that the initiative by the University of Pittsburgh and Johns Hopkins has potential to solve some ethical challenges involved in research use of biospecimens. “Compared to the system that allowed Lacks’s cells to be used without her permission, Shapiro said, “blockchain technology using nonfungible tokens that allow patients to follow their samples may enhance transparency, accountability and respect for persons who contribute their tissue and clinical data for research.”

Read more about laws that have prevented people from the rights to their own cells.

Monkeypox produces more telltale signs than COVID-19. Scientists think that a “ring” vaccination strategy can be used when these signs appear to help with squelching the current outbreak of this disease.

A new virus has emerged and stoked fears of another pandemic: monkeypox. Since May 2022, it has been detected in 29 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico among international travelers and their close contacts. On a worldwide scale, as of June 30, there have been 5,323 cases in 52 countries.

The good news: An existing vaccine can go a long way toward preventing a catastrophic outbreak. Because monkeypox is a close relative of smallpox, the same vaccine can be used—and it is about 85 percent effective against the virus, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Also on the plus side, monkeypox is less contagious with milder illness than smallpox and, compared to COVID-19, produces more telltale signs. Scientists think that a “ring” vaccination strategy can be used when these signs appear to help with squelching this alarming outbreak.

How it’s transmitted

Monkeypox spreads between people primarily through direct contact with infectious sores, scabs, or bodily fluids. People also can catch it through respiratory secretions during prolonged, face-to-face contact, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

As of June 30, there have been 396 documented monkeypox cases in the U.S., and the CDC has activated its Emergency Operations Center to mobilize additional personnel and resources. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is aiming to boost testing capacity and accessibility. No Americans have died from monkeypox during this outbreak but, during the COVID-19 pandemic (February 2020 to date), Africa has documented 12,141 cases and 363 deaths from monkeypox.

Ring vaccination proved effective in curbing the smallpox and Ebola outbreaks. As the monkeypox threat continues to loom, scientists view this as the best vaccine approach.

A person infected with monkeypox typically has symptoms—for instance, fever and chills—in a contagious state, so knowing when to avoid close contact with others makes it easier to curtail than COVID-19.

Advantages of ring vaccination

For this reason, it’s feasible to vaccinate a “ring” of people around the infected individual rather than inoculating large swaths of the population. Ring vaccination proved effective in curbing the smallpox and Ebola outbreaks. As the monkeypox threat continues to loom, scientists view this as the best vaccine approach.

With many infections, “it normally would make sense to everyone to vaccinate more widely,” says Wesley C. Van Voorhis, a professor and director of the Center for Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. However, “in this case, ring vaccination may be sufficient to contain the outbreak and also minimize the rare, but potentially serious side effects of the smallpox/monkeypox vaccine.”

There are two licensed smallpox vaccines in the United States: ACAM2000 (live Vaccina virus) and JYNNEOS (live virus non-replicating). The ACAM 2000, Van Voorhis says, is the old smallpox vaccine that, in rare instances, could spread diffusely within the body and cause heart problems, as well as severe rash in people with eczema or serious infection in immunocompromised patients.

To prevent organ damage, the current recommendation would be to use the JYNNEOS vaccine, says Phyllis Kanki, a professor of health sciences in the division of immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. However, according to a report on the CDC’s website, people with immunocompromising conditions could have a higher risk of getting a severe case of monkeypox, despite being vaccinated, and “might be less likely to mount an effective response after any vaccination, including after JYNNEOS.”

In the late 1960s, the ring vaccination strategy became part of the WHO’s mission to globally eradicate smallpox, with the last known natural case described in Somalia in 1977. Ring vaccination can also refer to how a clinical trial is designed, as was the case in 2015, when this approach was used for researching the benefits of an investigational Ebola vaccine in Guinea, Kanki says.

“Since Monkeypox spreads by close contact and we have an effective vaccine, vaccinating high-risk individuals and their contacts may be a good strategy to limit transmission,” she says, adding that privacy is an important ethical principle that comes into play, as people with monkeypox would need to disclose their close contacts so that they could benefit from ring vaccination.

Rapid identification of cases and contacts—along with their cooperation—is essential for ring vaccination to be effective. Although mass vaccination also may work, the risk of infection to most of the population remains low while supply of the JYNNEOS vaccine is limited, says Stanley Deresinski, a clinical professor of medicine in the Infectious Disease Clinic at Stanford University School of Medicine.

Other strategies for preventing transmission

Ideally, the vaccine should be administered within four days of an exposure, but it’s recommended for up to 14 days. The WHO also advocates more widespread vaccination campaigns in the population segment with the most cases so far: men who engage in sex with other men.

The virus appears to be spreading in sexual networks, which differs from what was seen in previously reported outbreaks of monkeypox (outside of Africa), where risk was associated with travel to central or west Africa or various types of contact with individuals or animals from those locales. There is no evidence of transmission by food, but contaminated articles in the environment such as bedding are potential sources of the virus, Deresinski says.

Severe cases of monkeypox can occur, but “transmission of the virus requires close contact,” he says. “There is no evidence of aerosol transmission, as occurs with SARS-CoV-2, although it must be remembered that the smallpox virus, a close relative of monkeypox, was transmitted by aerosol.”

Deresinski points to the fact that in 2003, monkeypox was introduced into the U.S. through imports from Ghana of infected small mammals, such as Gambian giant rats, as pets. They infected prairie dogs, which also were sold as pets and, ultimately, this resulted in 37 confirmed transmissions to humans and 10 probable cases. A CDC investigation identified no cases of human-to-human transmission. Then, in 2021, a traveler flew from Nigeria to Dallas through Atlanta, developing skin lesions several days after arrival. Another CDC investigation yielded 223 contacts, although 85 percent were deemed to be at only minimal risk and the remainder at intermediate risk. No new cases were identified.

How much should we be worried

But how serious of a threat is monkeypox this time around? “Right now, the risk to the general public is very low,” says Scott Roberts, an assistant professor and associate medical director of infection prevention at Yale School of Medicine. “Monkeypox is spread through direct contact with infected skin lesions or through close contact for a prolonged period of time with an infected person. It is much less transmissible than COVID-19.”

The monkeypox incubation period—the time from infection until the onset of symptoms—is typically seven to 14 days but can range from five to 21 days, compared with only three days for the Omicron variant of COVID-19. With such a long incubation, there is a larger window to conduct contact tracing and vaccinate people before symptoms appear, which can prevent infection or lessen the severity.

But symptoms may present atypically or recognition may be delayed. “Ring vaccination works best with 100 percent adherence, and in the absence of a mandate, this is not achievable,” Roberts says.

At the outset of infection, symptoms include fever, chills, and fatigue. Several days later, a rash becomes noticeable, usually beginning on the face and spreading to other parts of the body, he says. The rash starts as flat lesions that raise and develop fluid, similar to manifestations of chickenpox. Once the rash scabs and falls off, a person is no longer contagious.

“It's an uncomfortable infection,” says Van Voorhis, the University of Washington School of Medicine professor. There may be swollen lymph nodes. Sores and rash are often limited to the genitals and areas around the mouth or rectum, suggesting intimate contact as the source of spread.

Symptoms of monkeypox usually last from two to four weeks. The WHO estimated that fatalities range from 3 to 6 percent. Although it’s believed to infect various animal species, including rodents and monkeys in west and central Africa, “the animal reservoir for the virus is unknown,” says Kanki, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health professor.

Too often, viruses originate in parts of the world that are too poor to grapple with them and may lack the resources to invest in vaccines and treatments. “This disease is endemic in central and west Africa, and it has basically been ignored until it jumped to the north and infected Europeans, Americans, and Canadians,” Van Voorhis says. “We have to do a better job in health care and prevention all over the world. This is the kind of thing that comes back to bite us.”

Interventions in health and safety often yield results that are the opposite of what policymakers were hoping for. Officials can take a science-based approach by measuring what really works instead of relying on gut intuitions.

nudgesYou are driving along the highway and see an electronic sign that reads: “3,238 traffic deaths this year.” Do you think this reminder of roadside mortality would change how you drive? According to a recent, peer-reviewed study in Science, seeing that sign would make you more likely to crash. That’s ironic, given that the sign’s creators assumed it would make you safer.

The study, led by a pair of economists at the University of Toronto and University of Minnesota, examined seven years of traffic accident data from 880 electric highway sign locations in Texas, which experienced 4,480 fatalities in 2021. For one week of each month, the Texas Department of Transportation posts the latest fatality messages on signs along select traffic corridors as part of a safety campaign. Their logic is simple: Tell people to drive with care by reminding them of the dangers on the road.

But when the researchers looked at the data, they found that the number of crashes increased by 1.52 percent within three miles of these signs when compared with the same locations during the same month in previous years when signs did not show fatality information. That impact is similar to raising the speed limit by four miles or decreasing the number of highway troopers by 10 percent.

The scientists calculated that these messages contributed to 2,600 additional crashes and 16 deaths annually. They also found a social cost, meaning the financial expense borne by society as a whole due to these crashes, of $377 million per year, in Texas alone.

The cause, they argue, is distracted driving. Much like incoming texts or phone calls, these “in-your-face” messages grab your attention and undermine your focus on the road. The signs are particularly distracting and dangerous because, in communicating that many people died doing exactly what you are doing, they cause anxiety. Supporting this hypothesis, the scientists discovered that crashes increase when the signs report higher numbers of deaths. Thus, later in the year, as that total mortality figure goes up, so do the percentage of crashes.

Boomerang effects happen when those with authority, in government or business, fail to pay attention to the science. These leaders rely on armchair psychology and gut intuitions on what should work, rather than measuring what does work.

That change over time is not simply a function of changing weather, the study’s authors observed. They also found that the increase in car crashes is greatest in more complex road segments, which require greater focus to navigate.

The overall findings represent what behavioral scientists like myself call a “boomerang effect,” meaning an intervention that produces consequences opposite to those intended. Unfortunately, these effects are all too common. Between 1998 and 2004, Congress funded the $1 billion National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign, which famously boomeranged. Using professional advertising and public relations firms, the campaign bombarded kids aged 9 to 18 with anti-drug messaging, focused on marijuana, on TV, radio, magazines, and websites. A 2008 study funded by the National Institutes of Health found that children and teens saw these ads two to three times per week. However, more exposure to this advertising increased the likelihood that youth used marijuana. Why? Surveys and interviews suggested that young people who saw the ads got the impression that many of their peers used marijuana. As a result, they became more likely to use the drug themselves.

Boomerang effects happen when those with authority, in government or business, fail to pay attention to the science. These leaders rely on armchair psychology and gut intuitions on what should work, rather than measuring what does work.

To be clear, message campaigns—whether on electronic signs or through advertisements—can have a substantial effect on behavior. Extensive research reveals that people can be influenced by “nudges,” which shape the environment to influence their behavior in a predictable manner. For example, a successful campaign to reduce car accidents involved sending smartphone notifications that helped drivers evaluate their performance after each trip. These messages informed drivers of their personal average and best performance, as measured by accelerometers and gyroscopes. The campaign, which ran over 21 months, significantly reduced accident frequency.

Nudges work best when rigorously tested with small-scale experiments that evaluate their impact. Because behavioral scientists are infrequently consulted in creating these policies, some studies suggest that only 62 percent have a statistically significant effect. Other research reveals that up to 15 percent of desired interventions may backfire.

In the case of roadside mortality signage, the data are damning. The new research based on the Texas signs aligns with several past studies. For instance, research has shown that increasing people’s anxiety causes them to drive worse. Another, a Virginia Tech study in a laboratory setting, found that showing drivers fatality messages increased what psychologists call “cognitive load,” or the amount of information your brain is processing, with emotionally-salient information being especially burdensome and preoccupying, thus causing more distraction.

Nonetheless, Texas, along with at least 28 other states, has pursued mortality messaging campaigns since 2012, without testing them effectively. Behavioral science is critical here: when road signs are tested by people without expertise in how minds work, the results are often counterproductive. For example, the Virginia Tech research looked at road signs that used humor, popular culture, sports, and other nontraditional themes with the goal of provoking an emotional response. When they measured how participants responded to these signs, they noticed greater cognitive activation and attention in the brain. Thus, the researchers decided, the signs worked. But a behavioral scientist would note that increased attention likely contributes to the signs’ failure. As the just-published study in Science makes clear, distracting, emotionally-loaded signs are dangerous to drivers.

But there is good news. First, in most cases, it’s very doable to run an effective small-scale study testing an intervention. States could set up a safety campaign with a few electric signs in a diversity of settings and evaluate the impact over three months on driver crashes after seeing the signs. Policymakers could ask researchers to track the data as they run ads for a few months in a variety of nationally representative markets for a few months and assess their effectiveness. They could also ask behavioral scientists whether their proposals are well designed, whether similar policies have been tried previously in other places, and how these policies have worked in practice.

Everyday citizens can write to and call their elected officials to ask them to make this kind of research a priority before embracing an untested safety campaign. More broadly, you can encourage them to avoid relying on armchair psychology and to test their intuitions before deploying initiatives that might place the public under threat.