Blood Money: Paying for Convalescent Plasma to Treat COVID-19

A bag of plasma that Tom Hanks donated back in April 2020 after his coronavirus infection. (He was not paid to donate.)

Convalescent plasma – first used to treat diphtheria in 1890 – has been dusted off the shelf to treat COVID-19. Does it work? Should we rely strictly on the altruism of donors or should people be paid for it?

The biologic theory is that a person who has recovered from a disease has chemicals in their blood, most likely antibodies, that contributed to their recovery, and transferring those to a person who is sick might aid their recovery. Whole blood won't work because there are too few antibodies in a single unit of blood and the body can hold only so much of it.

Plasma comprises about 55 percent of whole blood and is what's left once you take out the red blood cells that carry oxygen and the white blood cells of the immune system. Most of it is water but the rest is a complex mix of fats, salts, signaling molecules and proteins produced by the immune system, including antibodies.

A process called apheresis circulates the donors' blood through a machine that separates out the desired parts of blood and returns the rest to the donor. It takes several times the length of a regular whole blood donation to cycle through enough blood for the process. The end product is a yellowish concentration called convalescent plasma.

Recent History

It was used extensively during the great influenza epidemic off 1918 but fell out of favor with the development of antibiotics. Still, whenever a new disease emerges – SARS, MERS, Ebola, even antibiotic-resistant bacteria – doctors turn to convalescent plasma, often as a stopgap until more effective antibiotic and antiviral drugs are developed. The process is certainly safe when standard procedures for handling blood products are followed, and historically it does seem to be beneficial in at least some patients if administered early enough in the disease.

With few good treatment options for COVID-19, doctors have given convalescent plasma to more than a hundred thousand Americans and tens of thousand of people elsewhere, to mixed results. Placebo-controlled trials could give a clearer picture of plasma's value but it is difficult to enroll patients facing possible death when the flip of a coin will determine who will receive a saline solution or plasma.

And the plasma itself isn't some uniform pill stamped out in a factory, it's a natural product that is shaped by the immune history of the donor's body and its encounter not just with SARS-CoV-2 but a lifetime of exposure to different pathogens.

Researchers believe antibodies in plasma are a key factor in directly fighting the virus. But the variety and quantity of antibodies vary from donor to donor, and even over time from the same donor because once the immune system has cleared the virus from the body, it stops putting out antibodies to fight the virus. Often the quality and quantity of antibodies being given to a patient are not measured, making it somewhat hit or miss, which is why several companies have recently developed monoclonal antibodies, a single type of antibody found in blood that is effective against SARS-CoV-2 and that is multiplied in the lab for use as therapy.

Plasma may also contain other unknown factors that contribute to fighting disease, say perhaps signaling molecules that affect gene expression, which might affect the movement of immune cells, their production of antiviral molecules, or the regulation of inflammation. The complexity and lack of standardization makes it difficult to evaluate what might be working or not with a convalescent plasma treatment. Thus researchers are left with few clues about how to make it more effective.

Industrializing Plasma

Many Americans living along the border with Mexico regularly head south to purchase prescription drugs at a significant discount. Less known is the medical traffic the other way, Mexicans who regularly head north to be paid for plasma donations, which are prohibited in their country; the U.S. allows payment for plasma donations but not whole blood. A typical payment is about $35 for a donation but the sudden demand for convalescent plasma from people who have recovered from COVID-19 commands a premium price, sometimes as high as $200. These donors are part of a fast-growing plasma industry that surpassed $25 billion in 2018. The U.S. supplies about three-quarters of the world's needs for plasma.

Payment for whole blood donation in the U.S. is prohibited, and while payment for plasma is allowed, there is a stigma attached to payment and much plasma is donated for free.

The pharmaceutical industry has shied away from natural products they cannot patent but they have identified simpler components from plasma, such as clotting factors and immunoglobulins, that have been turned into useful drugs from this raw material of plasma. While some companies have retooled to provide convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19, often paying those donors who have recovered a premium of several times the normal rate, most convalescent plasma has come as donations through traditional blood centers.

In April the Mayo Clinic, in cooperation with the FDA, created an expanded access program for convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19. It was meant to reduce the paperwork associated with gaining access to a treatment not yet approved by the FDA for that disease. Initially it was supposed to be for 5000 units but it quickly grew to more than twenty times that size. Michael Joyner, the head of the program, discussed that experience in an extended interview in September.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) also created associated reimbursement codes, which became permanent in August.

Mayo published an analysis of the first 35,000 patients as a preprint in August. It concluded, "The relationships between mortality and both time to plasma transfusion, and antibody levels provide a signature that is consistent with efficacy for the use of convalescent plasma in the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients."

It seemed to work best when given early in infection and in larger doses; a similar pattern has been seen in studies of monoclonal antibodies. A revised version will soon be published in a major medical journal. Some criticized the findings as not being from a randomized clinical trial.

Convalescent plasma is not the only intervention that seems to work better when used earlier in the course of disease. Recently the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly stopped a clinical trial of a monoclonal antibody in hospitalized COVID-19 patients when it became apparent it wasn't helping. It is continuing trials for patients who are less sick and begin treatment earlier, as well as in persons who have been exposed to the virus but not yet diagnosed as infected, to see if it might prevent infection. In November the FDA eased access to this drug outside of clinical trials, though it is not yet approved for sale.

Show Me the Money

The antibodies that seem to give plasma its curative powers are fragile proteins that the body produces to fight the virus. Production shuts down once the virus is cleared and the remaining antibodies survive only for a few weeks before the levels fade. [Vaccines are used to train immune cells to produce antibodies and other defenses to respond to exposure to future pathogens.] So they can be usefully harvested from a recovered patient for only a few short weeks or months before they decline precipitously. The question becomes, how does one mobilize this resource in that short window of opportunity?

The program run by the Mayo Clinic explains the process and criteria for donating convalescent plasma for COVID-19, as well as links to local blood centers equipped to handle those free donations. Commercial plasma centers also are advertising and paying for donations.

A majority of countries prohibit paying donors for blood or blood products, including India. But an investigation by India Today touted a black market of people willing to donate convalescent plasma for the equivalent of several hundred dollars. Officials vowed to prosecute, saying donations should be selfless.

But that enforcement threat seemed to be undercut when the health minister of the state of Assam declared "plasma donors will get preference in several government schemes including the government job interview." It appeared to be a form of compensation that far surpassed simple cash.

The small city of Rexburg, Idaho, with a population a bit over 50,000, overwhelmingly Mormon and home to a campus of Brigham Young University, at one point had one of the highest per capita rates of COVID-19 in the current wave of infection. Rumors circulated that some students were intentionally trying to become infected so they could later sell their plasma for top dollar, potentially as much as $200 a visit.

Troubled university officials investigated the allegations but could come up with nothing definitive; how does one prove intentionality with such an omnipresent yet elusive virus? They chalked it up to idle chatter, perhaps an urban legend, which might be associated with alcohol use on some other campus.

Doctors, hospitals, and drug companies are all rightly praised for their altruism in the fight against COVID-19, but they also get paid. Payment for whole blood donation in the U.S. is prohibited, and while payment for plasma is allowed, there is a stigma attached to payment and much plasma is donated for free. "Why do we expect the donors [of convalescent plasma] to be the only uncompensated people in the process? It really makes no sense," argues Mark Yarborough, an ethicist at the UC Davis School of Medicine in Sacramento.

"When I was in grad school, two of my closest friends, at least once a week they went and gave plasma. That was their weekend spending money," Yarborough recalls. He says upper and middle-income people may have the luxury of donating blood products but prohibiting people from selling their plasma is a bit paternalistic and doesn't do anything to improve the economic status of poor people.

"Asking people to dedicate two hours a week for an entire year in exchange for cookies and milk is demonstrably asking too much," says Peter Jaworski, an ethicist who teaches at Georgetown University.

He notes that companies that pay plasma donors have much lower total costs than do operations that rely solely on uncompensated donations. The companies have to spend less to recruit and retain donors because they increase payments to encourage regular repeat donations. They are able to more rationally schedule visits to maximize use of expensive apheresis equipment and medical personnel used for the collection.

It seems that COVID-19 has been with us forever, but in reality it is less than a year. We have learned much over that short time, can now better manage the disease, and have lower mortality rates to prove it. Just how much convalescent plasma may have contributed to that remains an open question. Access to vaccines is months away for many people, and even then some people will continue to get sick. Given the lack of proven treatments, it makes sense to keep plasma as part of the mix, and not close the door to any legitimate means to obtain it.

DNA- and RNA-based electronic implants may revolutionize healthcare

The test tubes contain tiny DNA/enzyme-based circuits, which comprise TRUMPET, a new type of electronic device, smaller than a cell.

Implantable electronic devices can significantly improve patients’ quality of life. A pacemaker can encourage the heart to beat more regularly. A neural implant, usually placed at the back of the skull, can help brain function and encourage higher neural activity. Current research on neural implants finds them helpful to patients with Parkinson’s disease, vision loss, hearing loss, and other nerve damage problems. Several of these implants, such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink, have already been approved by the FDA for human use.

Yet, pacemakers, neural implants, and other such electronic devices are not without problems. They require constant electricity, limited through batteries that need replacements. They also cause scarring. “The problem with doing this with electronics is that scar tissue forms,” explains Kate Adamala, an assistant professor of cell biology at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. “Anytime you have something hard interacting with something soft [like muscle, skin, or tissue], the soft thing will scar. That's why there are no long-term neural implants right now.” To overcome these challenges, scientists are turning to biocomputing processes that use organic materials like DNA and RNA. Other promised benefits include “diagnostics and possibly therapeutic action, operating as nanorobots in living organisms,” writes Evgeny Katz, a professor of bioelectronics at Clarkson University, in his book DNA- And RNA-Based Computing Systems.

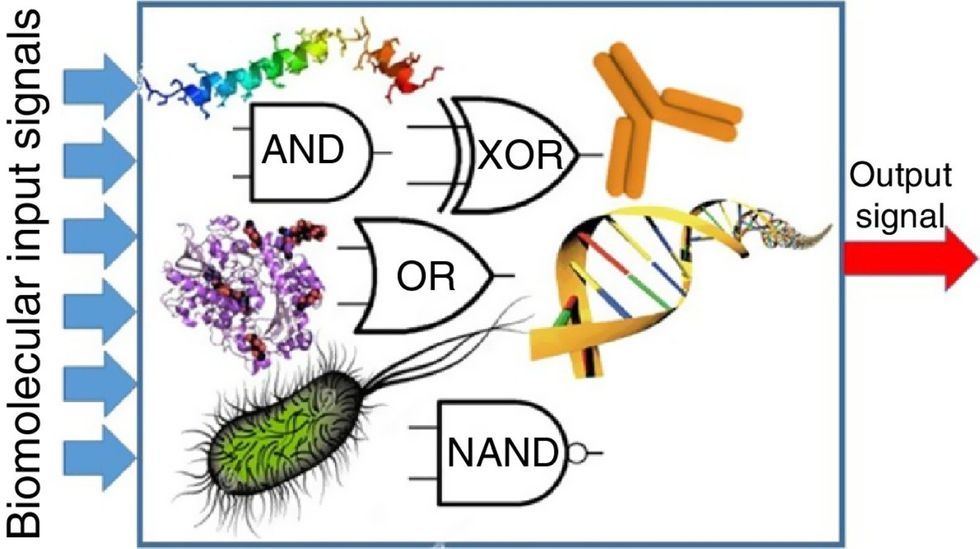

While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output.

Adamala’s research focuses on developing such biocomputing systems using DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids. Using these molecules in the biocomputing systems allows the latter to be biocompatible with the human body, resulting in a natural healing process. In a recent Nature Communications study, Adamala and her team created a new biocomputing platform called TRUMPET (Transcriptional RNA Universal Multi-Purpose GatE PlaTform) which acts like a DNA-powered computer chip. “These biological systems can heal if you design them correctly,” adds Adamala. “So you can imagine a computer that will eventually heal itself.”

The basics of biocomputing

Biocomputing and regular computing have many similarities. Like regular computing, biocomputing works by running information through a series of gates, usually logic gates. A logic gate works as a fork in the road for an electronic circuit. The input will travel one way or another, giving two different outputs. An example logic gate is the AND gate, which has two inputs (A and B) and two different results. If both A and B are 1, the AND gate output will be 1. If only A is 1 and B is 0, the output will be 0 and vice versa. If both A and B are 0, the result will be 0. While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output. In this case, the DNA enters the logic gate as a single or double strand.

If the DNA is double-stranded, the system “digests” the DNA or destroys it, which results in non-fluorescence or “0” output. Conversely, if the DNA is single-stranded, it won’t be digested and instead will be copied by several enzymes in the biocomputing system, resulting in fluorescent RNA or a “1” output. And the output for this type of binary system can be expanded beyond fluorescence or not. For example, a “1” output might be the production of the enzyme insulin, while a “0” may be that no insulin is produced. “This kind of synergy between biology and computation is the essence of biocomputing,” says Stephanie Forrest, a professor and the director of the Biodesign Center for Biocomputing, Security and Society at Arizona State University.

Biocomputing circles are made of DNA, RNA, proteins and even bacteria.

Evgeny Katz

The TRUMPET’s promise

Depending on whether the biocomputing system is placed directly inside a cell within the human body, or run in a test-tube, different environmental factors play a role. When an output is produced inside a cell, the cell's natural processes can amplify this output (for example, a specific protein or DNA strand), creating a solid signal. However, these cells can also be very leaky. “You want the cells to do the thing you ask them to do before they finish whatever their businesses, which is to grow, replicate, metabolize,” Adamala explains. “However, often the gate may be triggered without the right inputs, creating a false positive signal. So that's why natural logic gates are often leaky." While biocomputing outside a cell in a test tube can allow for tighter control over the logic gates, the outputs or signals cannot be amplified by a cell and are less potent.

TRUMPET, which is smaller than a cell, taps into both cellular and non-cellular biocomputing benefits. “At its core, it is a nonliving logic gate system,” Adamala states, “It's a DNA-based logic gate system. But because we use enzymes, and the readout is enzymatic [where an enzyme replicates the fluorescent RNA], we end up with signal amplification." This readout means that the output from the TRUMPET system, a fluorescent RNA strand, can be replicated by nearby enzymes in the platform, making the light signal stronger. "So it combines the best of both worlds,” Adamala adds.

These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body.

The TRUMPET biocomputing process is relatively straightforward. “If the DNA [input] shows up as single-stranded, it will not be digested [by the logic gate], and you get this nice fluorescent output as the RNA is made from the single-stranded DNA, and that's a 1,” Adamala explains. "And if the DNA input is double-stranded, it gets digested by the enzymes in the logic gate, and there is no RNA created from the DNA, so there is no fluorescence, and the output is 0." On the story's leading image above, if the tube is "lit" with a purple color, that is a binary 1 signal for computing. If it's "off" it is a 0.

While still in research, TRUMPET and other biocomputing systems promise significant benefits to personalized healthcare and medicine. These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body. The study’s lead author and graduate student Judee Sharon is already beginning to research TRUMPET's ability for earlier cancer diagnoses. Because the inputs for TRUMPET are single or double-stranded DNA, any mutated or cancerous DNA could theoretically be detected from the platform through the biocomputing process. Theoretically, devices like TRUMPET could be used to detect cancer and other diseases earlier.

Adamala sees TRUMPET not only as a detection system but also as a potential cancer drug delivery system. “Ideally, you would like the drug only to turn on when it senses the presence of a cancer cell. And that's how we use the logic gates, which work in response to inputs like cancerous DNA. Then the output can be the production of a small molecule or the release of a small molecule that can then go and kill what needs killing, in this case, a cancer cell. So we would like to develop applications that use this technology to control the logic gate response of a drug’s delivery to a cell.”

Although platforms like TRUMPET are making progress, a lot more work must be done before they can be used commercially. “The process of translating mechanisms and architecture from biology to computing and vice versa is still an art rather than a science,” says Forrest. “It requires deep computer science and biology knowledge,” she adds. “Some people have compared interdisciplinary science to fusion restaurants—not all combinations are successful, but when they are, the results are remarkable.”

Crickets are low on fat, high on protein, and can be farmed sustainably. They are also crunchy.

In today’s podcast episode, Leaps.org Deputy Editor Lina Zeldovich speaks about the health and ecological benefits of farming crickets for human consumption with Bicky Nguyen, who joins Lina from Vietnam. Bicky and her business partner Nam Dang operate an insect farm named CricketOne. Motivated by the idea of sustainable and healthy protein production, they started their unconventional endeavor a few years ago, despite numerous naysayers who didn’t believe that humans would ever consider munching on bugs.

Yet, making creepy crawlers part of our diet offers many health and planetary advantages. Food production needs to match the rise in global population, estimated to reach 10 billion by 2050. One challenge is that some of our current practices are inefficient, polluting and wasteful. According to nonprofit EarthSave.org, it takes 2,500 gallons of water, 12 pounds of grain, 35 pounds of topsoil and the energy equivalent of one gallon of gasoline to produce one pound of feedlot beef, although exact statistics vary between sources.

Meanwhile, insects are easy to grow, high on protein and low on fat. When roasted with salt, they make crunchy snacks. When chopped up, they transform into delicious pâtes, says Bicky, who invents her own cricket recipes and serves them at industry and public events. Maybe that’s why some research predicts that edible insects market may grow to almost $10 billion by 2030. Tune in for a delectable chat on this alternative and sustainable protein.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Further reading:

More info on Bicky Nguyen

https://yseali.fulbright.edu.vn/en/faculty/bicky-n...

The environmental footprint of beef production

https://www.earthsave.org/environment.htm

https://www.watercalculator.org/news/articles/beef-king-big-water-footprints/

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00005/full

https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-footprint-food-methane

Insect farming as a source of sustainable protein

https://www.insectgourmet.com/insect-farming-growing-bugs-for-protein/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/insect-farming

Cricket flour is taking the world by storm

https://www.cricketflours.com/

https://talk-commerce.com/blog/what-brands-use-cricket-flour-and-why/

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.