FDA, researchers work to make clinical trials more diverse

The U.S. population is becoming more diverse, but clinical trials don't reflect that, experts say. Some are focusing on recruiting minorities to participate in research.

Nestled in a predominately Hispanic neighborhood, a new mural outside Guadalupe Centers Middle School in Kansas City, Missouri imparts a powerful message: “Clinical Research Needs Representation.” The colorful portraits painted above those words feature four cancer survivors of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. Two individuals identify as Hispanic, one as African American and another as Native American.

One of the patients depicted in the mural is Kim Jones, a 51-year-old African American breast cancer survivor since 2012. She advocated for an African American friend who participated in several clinical trials for ovarian cancer. Her friend was diagnosed in an advanced stage at age 26 but lived nine more years, thanks to the trials testing new therapeutics. “They are definitely giving people a longer, extended life and a better quality of life,” said Jones, who owns a nail salon. And that’s the message the mural aims to send to the community: Clinical trials need diverse participants.

While racial and ethnic minority groups represent almost half of the U.S. population, the lack of diversity in clinical trials poses serious challenges. Limited awareness and access impede equitable representation, which is necessary to prove the safety and effectiveness of medical interventions across different groups.

A Yale University study on clinical trial diversity published last year in BMJ Medicine found that while 81 percent of trials testing the new cancer drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration between 2012 and 2017 included women, only 23 percent included older adults and 5 percent fairly included racial and ethnic minorities. “It’s both a public health and social justice issue,” said Jennifer E. Miller, an associate professor of medicine at Yale School of Medicine. “We need to know how medicines and vaccines work for all clinically distinct groups, not just healthy young White males.” A recent JAMA Oncology editorial stresses out the need for legislation that would require diversity action plans for certain types of trials.

Ensuring meaningful representation of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials for regulated medical products is fundamental to public health.--FDA Commissioner Robert M. Califf.

But change is on the horizon. Last April, the FDA issued a new draft guidance encouraging industry to find ways to revamp recruitment into clinical trials. The announcement, which expanded on previous efforts, called for including more participants from underrepresented racial and ethnic segments of the population.

“The U.S. population has become increasingly diverse, and ensuring meaningful representation of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials for regulated medical products is fundamental to public health,” FDA commissioner Robert M. Califf, a physician, said in a statement. “Going forward, achieving greater diversity will be a key focus throughout the FDA to facilitate the development of better treatments and better ways to fight diseases that often disproportionately impact diverse communities. This guidance also further demonstrates how we support the Administration’s Cancer Moonshot goal of addressing inequities in cancer care, helping to ensure that every community in America has access to cutting-edge cancer diagnostics, therapeutics and clinical trials.”

Lola Fashoyin-Aje, associate director for Science and Policy to Address Disparities in the Oncology Center of Excellence at the FDA, said that the agency “has long held the view that clinical trial participants should reflect the clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients who will ultimately receive the drug once approved.” However, “numerous studies over many decades” have measured the extent of underrepresentation. One FDA analysis found that the proportion of White patients enrolled in U.S. clinical trials (88 percent) is much higher than their numbers in country's population. Meanwhile, the enrollment of African American and Native Hawaiian/American Indian and Alaskan Native patients is below their national numbers.

The FDA’s guidance is accelerating researchers’ efforts to be more inclusive of diverse groups in clinical trials, said Joyce Sackey, a clinical professor of medicine and associate dean at Stanford School of Medicine. Underrepresentation is “a huge issue,” she noted. Sackey is focusing on this in her role as the inaugural chief equity, diversity and inclusion officer at Stanford Medicine, which encompasses the medical school and two hospitals.

Until the early 1990s, Sackey pointed out, clinical trials were based on research that mainly included men, as investigators were concerned that women could become pregnant, which would affect the results. This has led to some unfortunate consequences, such as indications and dosages for drugs that cause more side effects in women due to biological differences. “We’ve made some progress in including women, but we have a long way to go in including people of different ethnic and racial groups,” she said.

A new mural outside Guadalupe Centers Middle School in Kansas City, Missouri, advocates for increasing diversity in clinical trials. Kim Jones, 51-year-old African American breast cancer survivor, is second on the left.

Artwork by Vania Soto. Photo by Megan Peters.

Among racial and ethnic minorities, distrust of clinical trials is deeply rooted in a history of medical racism. A prime example is the Tuskegee Study, a syphilis research experiment that started in 1932 and spanned 40 years, involving hundreds of Black men with low incomes without their informed consent. They were lured with inducements of free meals, health care and burial stipends to participate in the study undertaken by the U.S. Public Health Service and the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

By 1947, scientists had figured out that they could provide penicillin to help patients with syphilis, but leaders of the Tuskegee research failed to offer penicillin to their participants throughout the rest of the study, which lasted until 1972.

Opeyemi Olabisi, an assistant professor of medicine at Duke University Medical Center, aims to increase the participation of African Americans in clinical research. As a nephrologist and researcher, he is the principal investigator of a clinical trial focusing on the high rate of kidney disease fueled by two genetic variants of the apolipoprotein L1 (APOL1) gene in people of recent African ancestry. Individuals of this background are four times more likely to develop kidney failure than European Americans, with these two variants accounting for much of the excess risk, Olabisi noted.

The trial is part of an initiative, CARE and JUSTICE for APOL1-Mediated Kidney Disease, through which Olabisi hopes to diversify study participants. “We seek ways to engage African Americans by meeting folks in the community, providing accessible information and addressing structural hindrances that prevent them from participating in clinical trials,” Olabisi said. The researchers go to churches and community organizations to enroll people who do not visit academic medical centers, which typically lead clinical trials. Since last fall, the initiative has screened more than 250 African Americans in North Carolina for the genetic variants, he said.

Other key efforts are underway. “Breaking down barriers, including addressing access, awareness, discrimination and racism, and workforce diversity, are pivotal to increasing clinical trial participation in racial and ethnic minority groups,” said Joshua J. Joseph, assistant professor of medicine at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Along with the university’s colleges of medicine and nursing, researchers at the medical center partnered with the African American Male Wellness Agency, Genentech and Pfizer to host webinars soliciting solutions from almost 450 community members, civic representatives, health care providers, government organizations and biotechnology professionals in 25 states and five countries.

Their findings, published in February in the journal PLOS One, suggested that including incentives or compensation as part of the research budget at the institutional level may help resolve some issues that hinder racial and ethnic minorities from participating in clinical trials. Compared to other groups, more Blacks and Hispanics have jobs in service, production and transportation, the authors note. It can be difficult to get paid leave in these sectors, so employees often can’t join clinical trials during regular business hours. If more leaders of trials offer money for participating, that could make a difference.

Obstacles include geographic access, language and other communications issues, limited awareness of research options, cost and lack of trust.

Christopher Corsico, senior vice president of development at GSK, formerly GlaxoSmithKline, said the pharmaceutical company conducted a 17-year retrospective study on U.S. clinical trial diversity. “We are using epidemiology and patients most impacted by a particular disease as the foundation for all our enrollment guidance, including study diversity plans,” Corsico said. “We are also sharing our results and ideas across the pharmaceutical industry.”

Judy Sewards, vice president and head of clinical trial experience at Pfizer’s headquarters in New York, said the company has committed to achieving racially and ethnically diverse participation at or above U.S. census or disease prevalence levels (as appropriate) in all trials. “Today, barriers to clinical trial participation persist,” Sewards said. She noted that these obstacles include geographic access, language and other communications issues, limited awareness of research options, cost and lack of trust. “Addressing these challenges takes a village. All stakeholders must come together and work collaboratively to increase diversity in clinical trials.”

It takes a village indeed. Hope Krebill, executive director of the Masonic Cancer Alliance, the outreach network of the University of Kansas Cancer Center in Kansas City, which commissioned the mural, understood that well. So her team actively worked with their metaphorical “village.” “We partnered with the community to understand their concerns, knowledge and attitudes toward clinical trials and research,” said Krebill. “With that information, we created a clinical trials video and a social media campaign, and finally, the mural to encourage people to consider clinical trials as an option for care.”

Besides its encouraging imagery, the mural will also be informational. It will include a QR code that viewers can scan to find relevant clinical trials in their location, said Vania Soto, a Mexican artist who completed the rendition in late February. “I’m so honored to paint people that are survivors and are living proof that clinical trials worked for them,” she said.

Jones, the cancer survivor depicted in the mural, hopes the image will prompt people to feel more open to partaking in clinical trials. “Hopefully, it will encourage people to inquire about what they can do — how they can participate,” she said.

DNA- and RNA-based electronic implants may revolutionize healthcare

The test tubes contain tiny DNA/enzyme-based circuits, which comprise TRUMPET, a new type of electronic device, smaller than a cell.

Implantable electronic devices can significantly improve patients’ quality of life. A pacemaker can encourage the heart to beat more regularly. A neural implant, usually placed at the back of the skull, can help brain function and encourage higher neural activity. Current research on neural implants finds them helpful to patients with Parkinson’s disease, vision loss, hearing loss, and other nerve damage problems. Several of these implants, such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink, have already been approved by the FDA for human use.

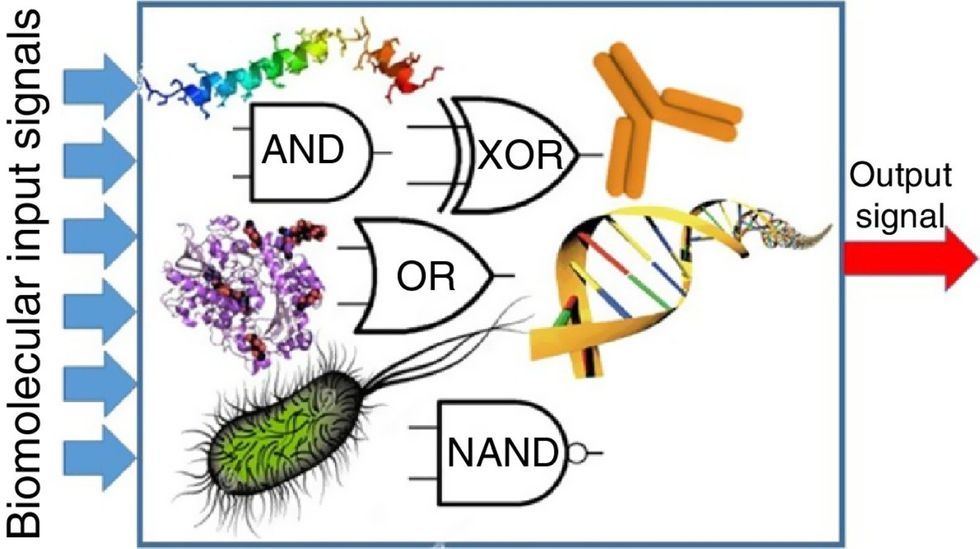

Yet, pacemakers, neural implants, and other such electronic devices are not without problems. They require constant electricity, limited through batteries that need replacements. They also cause scarring. “The problem with doing this with electronics is that scar tissue forms,” explains Kate Adamala, an assistant professor of cell biology at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. “Anytime you have something hard interacting with something soft [like muscle, skin, or tissue], the soft thing will scar. That's why there are no long-term neural implants right now.” To overcome these challenges, scientists are turning to biocomputing processes that use organic materials like DNA and RNA. Other promised benefits include “diagnostics and possibly therapeutic action, operating as nanorobots in living organisms,” writes Evgeny Katz, a professor of bioelectronics at Clarkson University, in his book DNA- And RNA-Based Computing Systems.

While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output.

Adamala’s research focuses on developing such biocomputing systems using DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids. Using these molecules in the biocomputing systems allows the latter to be biocompatible with the human body, resulting in a natural healing process. In a recent Nature Communications study, Adamala and her team created a new biocomputing platform called TRUMPET (Transcriptional RNA Universal Multi-Purpose GatE PlaTform) which acts like a DNA-powered computer chip. “These biological systems can heal if you design them correctly,” adds Adamala. “So you can imagine a computer that will eventually heal itself.”

The basics of biocomputing

Biocomputing and regular computing have many similarities. Like regular computing, biocomputing works by running information through a series of gates, usually logic gates. A logic gate works as a fork in the road for an electronic circuit. The input will travel one way or another, giving two different outputs. An example logic gate is the AND gate, which has two inputs (A and B) and two different results. If both A and B are 1, the AND gate output will be 1. If only A is 1 and B is 0, the output will be 0 and vice versa. If both A and B are 0, the result will be 0. While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output. In this case, the DNA enters the logic gate as a single or double strand.

If the DNA is double-stranded, the system “digests” the DNA or destroys it, which results in non-fluorescence or “0” output. Conversely, if the DNA is single-stranded, it won’t be digested and instead will be copied by several enzymes in the biocomputing system, resulting in fluorescent RNA or a “1” output. And the output for this type of binary system can be expanded beyond fluorescence or not. For example, a “1” output might be the production of the enzyme insulin, while a “0” may be that no insulin is produced. “This kind of synergy between biology and computation is the essence of biocomputing,” says Stephanie Forrest, a professor and the director of the Biodesign Center for Biocomputing, Security and Society at Arizona State University.

Biocomputing circles are made of DNA, RNA, proteins and even bacteria.

Evgeny Katz

The TRUMPET’s promise

Depending on whether the biocomputing system is placed directly inside a cell within the human body, or run in a test-tube, different environmental factors play a role. When an output is produced inside a cell, the cell's natural processes can amplify this output (for example, a specific protein or DNA strand), creating a solid signal. However, these cells can also be very leaky. “You want the cells to do the thing you ask them to do before they finish whatever their businesses, which is to grow, replicate, metabolize,” Adamala explains. “However, often the gate may be triggered without the right inputs, creating a false positive signal. So that's why natural logic gates are often leaky." While biocomputing outside a cell in a test tube can allow for tighter control over the logic gates, the outputs or signals cannot be amplified by a cell and are less potent.

TRUMPET, which is smaller than a cell, taps into both cellular and non-cellular biocomputing benefits. “At its core, it is a nonliving logic gate system,” Adamala states, “It's a DNA-based logic gate system. But because we use enzymes, and the readout is enzymatic [where an enzyme replicates the fluorescent RNA], we end up with signal amplification." This readout means that the output from the TRUMPET system, a fluorescent RNA strand, can be replicated by nearby enzymes in the platform, making the light signal stronger. "So it combines the best of both worlds,” Adamala adds.

These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body.

The TRUMPET biocomputing process is relatively straightforward. “If the DNA [input] shows up as single-stranded, it will not be digested [by the logic gate], and you get this nice fluorescent output as the RNA is made from the single-stranded DNA, and that's a 1,” Adamala explains. "And if the DNA input is double-stranded, it gets digested by the enzymes in the logic gate, and there is no RNA created from the DNA, so there is no fluorescence, and the output is 0." On the story's leading image above, if the tube is "lit" with a purple color, that is a binary 1 signal for computing. If it's "off" it is a 0.

While still in research, TRUMPET and other biocomputing systems promise significant benefits to personalized healthcare and medicine. These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body. The study’s lead author and graduate student Judee Sharon is already beginning to research TRUMPET's ability for earlier cancer diagnoses. Because the inputs for TRUMPET are single or double-stranded DNA, any mutated or cancerous DNA could theoretically be detected from the platform through the biocomputing process. Theoretically, devices like TRUMPET could be used to detect cancer and other diseases earlier.

Adamala sees TRUMPET not only as a detection system but also as a potential cancer drug delivery system. “Ideally, you would like the drug only to turn on when it senses the presence of a cancer cell. And that's how we use the logic gates, which work in response to inputs like cancerous DNA. Then the output can be the production of a small molecule or the release of a small molecule that can then go and kill what needs killing, in this case, a cancer cell. So we would like to develop applications that use this technology to control the logic gate response of a drug’s delivery to a cell.”

Although platforms like TRUMPET are making progress, a lot more work must be done before they can be used commercially. “The process of translating mechanisms and architecture from biology to computing and vice versa is still an art rather than a science,” says Forrest. “It requires deep computer science and biology knowledge,” she adds. “Some people have compared interdisciplinary science to fusion restaurants—not all combinations are successful, but when they are, the results are remarkable.”

Crickets are low on fat, high on protein, and can be farmed sustainably. They are also crunchy.

In today’s podcast episode, Leaps.org Deputy Editor Lina Zeldovich speaks about the health and ecological benefits of farming crickets for human consumption with Bicky Nguyen, who joins Lina from Vietnam. Bicky and her business partner Nam Dang operate an insect farm named CricketOne. Motivated by the idea of sustainable and healthy protein production, they started their unconventional endeavor a few years ago, despite numerous naysayers who didn’t believe that humans would ever consider munching on bugs.

Yet, making creepy crawlers part of our diet offers many health and planetary advantages. Food production needs to match the rise in global population, estimated to reach 10 billion by 2050. One challenge is that some of our current practices are inefficient, polluting and wasteful. According to nonprofit EarthSave.org, it takes 2,500 gallons of water, 12 pounds of grain, 35 pounds of topsoil and the energy equivalent of one gallon of gasoline to produce one pound of feedlot beef, although exact statistics vary between sources.

Meanwhile, insects are easy to grow, high on protein and low on fat. When roasted with salt, they make crunchy snacks. When chopped up, they transform into delicious pâtes, says Bicky, who invents her own cricket recipes and serves them at industry and public events. Maybe that’s why some research predicts that edible insects market may grow to almost $10 billion by 2030. Tune in for a delectable chat on this alternative and sustainable protein.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Further reading:

More info on Bicky Nguyen

https://yseali.fulbright.edu.vn/en/faculty/bicky-n...

The environmental footprint of beef production

https://www.earthsave.org/environment.htm

https://www.watercalculator.org/news/articles/beef-king-big-water-footprints/

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00005/full

https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-footprint-food-methane

Insect farming as a source of sustainable protein

https://www.insectgourmet.com/insect-farming-growing-bugs-for-protein/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/insect-farming

Cricket flour is taking the world by storm

https://www.cricketflours.com/

https://talk-commerce.com/blog/what-brands-use-cricket-flour-and-why/

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.