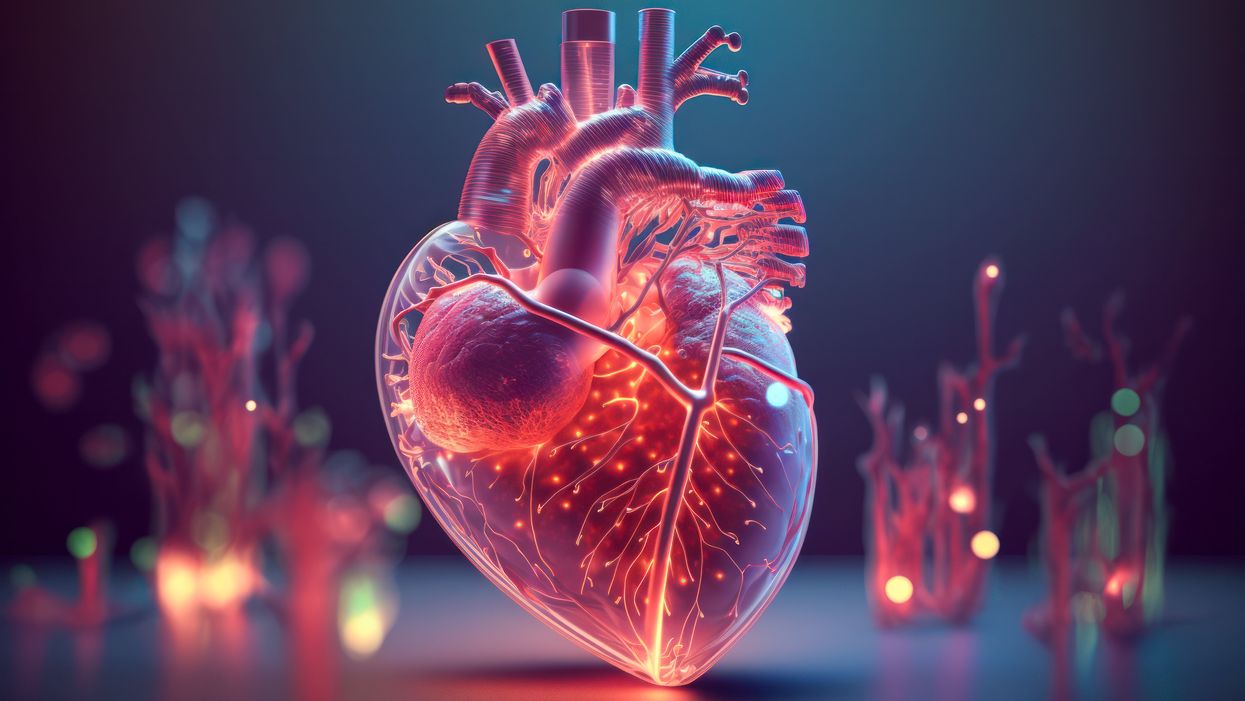

Scientists make progress with growing organs for transplants

Researchers from the University of Cambridge have laid the foundations for growing synthetic embryos that could develop a beating heart, gut and brain.

Story by Big Think

For over a century, scientists have dreamed of growing human organs sans humans. This technology could put an end to the scarcity of organs for transplants. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. The capability to grow fully functional organs would revolutionize research. For example, scientists could observe mysterious biological processes, such as how human cells and organs develop a disease and respond (or fail to respond) to medication without involving human subjects.

Recently, a team of researchers from the University of Cambridge has laid the foundations not just for growing functional organs but functional synthetic embryos capable of developing a beating heart, gut, and brain. Their report was published in Nature.

The organoid revolution

In 1981, scientists discovered how to keep stem cells alive. This was a significant breakthrough, as stem cells have notoriously rigorous demands. Nevertheless, stem cells remained a relatively niche research area, mainly because scientists didn’t know how to convince the cells to turn into other cells.

Then, in 1987, scientists embedded isolated stem cells in a gelatinous protein mixture called Matrigel, which simulated the three-dimensional environment of animal tissue. The cells thrived, but they also did something remarkable: they created breast tissue capable of producing milk proteins. This was the first organoid — a clump of cells that behave and function like a real organ. The organoid revolution had begun, and it all started with a boob in Jello.

For the next 20 years, it was rare to find a scientist who identified as an “organoid researcher,” but there were many “stem cell researchers” who wanted to figure out how to turn stem cells into other cells. Eventually, they discovered the signals (called growth factors) that stem cells require to differentiate into other types of cells.

For a human embryo (and its organs) to develop successfully, there needs to be a “dialogue” between these three types of stem cells.

By the end of the 2000s, researchers began combining stem cells, Matrigel, and the newly characterized growth factors to create dozens of organoids, from liver organoids capable of producing the bile salts necessary for digesting fat to brain organoids with components that resemble eyes, the spinal cord, and arguably, the beginnings of sentience.

Synthetic embryos

Organoids possess an intrinsic flaw: they are organ-like. They share some characteristics with real organs, making them powerful tools for research. However, no one has found a way to create an organoid with all the characteristics and functions of a real organ. But Magdalena Żernicka-Goetz, a developmental biologist, might have set the foundation for that discovery.

Żernicka-Goetz hypothesized that organoids fail to develop into fully functional organs because organs develop as a collective. Organoid research often uses embryonic stem cells, which are the cells from which the developing organism is created. However, there are two other types of stem cells in an early embryo: stem cells that become the placenta and those that become the yolk sac (where the embryo grows and gets its nutrients in early development). For a human embryo (and its organs) to develop successfully, there needs to be a “dialogue” between these three types of stem cells. In other words, Żernicka-Goetz suspected the best way to grow a functional organoid was to produce a synthetic embryoid.

As described in the aforementioned Nature paper, Żernicka-Goetz and her team mimicked the embryonic environment by mixing these three types of stem cells from mice. Amazingly, the stem cells self-organized into structures and progressed through the successive developmental stages until they had beating hearts and the foundations of the brain.

“Our mouse embryo model not only develops a brain, but also a beating heart [and] all the components that go on to make up the body,” said Żernicka-Goetz. “It’s just unbelievable that we’ve got this far. This has been the dream of our community for years and major focus of our work for a decade and finally we’ve done it.”

If the methods developed by Żernicka-Goetz’s team are successful with human stem cells, scientists someday could use them to guide the development of synthetic organs for patients awaiting transplants. It also opens the door to studying how embryos develop during pregnancy.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.

Podcast: The Friday Five weekly roundup in health research

This week's Friday Five covers promising research on a potential saliva test for post-traumatic stress disorder, cancer detection with a microchip, resilient food for climate change, the best posture for pill taking, and more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- Using graphene to repair shoulders

- Testing for PTSD with saliva

- Cancer detection with a microchip

- Best posture for pill taking

- Resilient food for climate change

And an honorable mention goes to research on a new way to induce healthy fat.

Podcast: The Science of Recharging Your Energy with Sara Mednick

For today's podcast episode, Leaps.org talks with Sara Mednick, author of The Power of the Downstate, a book about the science of relaxation - why it's so important, the best ways to get more of it, and the time of day when our bodies are biologically suited to enjoy it the most.

If you’re like me, you may have a case of email apnea, where you stop taking restful breaths when you open a work email. Or maybe you’re in the habit of shining blue light into your eyes long after sunset through your phone. Many of us are doing all kinds of things throughout the day that put us in a constant state of fight or flight arousal, with long-term impacts on health, productivity and happiness.

My guest for today’s episode is Sara Mednick, author of The Power of the Downstate, a book about the science of relaxation – why it’s so important, the best ways to go about getting more of it, and the time of day when our bodies are biologically suited to enjoy it the most. As a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of California, Irvine, Mednick has a great scientific background on this topic. After getting her PhD at Harvard, she filled her sleep lab with 7 bedrooms, and this is where she is federally funded to study people sleeping around the clock, with her research published in top journals such as Nature Neuroscience. She received the Office Naval Research Young Investigator Award in 2015, and her previous book, Take a Nap! Change Your Life was based on her groundbreaking research on the benefits of napping.

In our conversation, we talk about how work and society make it tough to get stimulation like food and exercise in ways that support our circadian rhythms, and there just as many obstacles to getting sleep and restoration like our ancestors enjoyed for 99 percent of human history. Sara shares some fascinating ways to get around these challenges, as well as her insights about the importance of exposure to daylight and nature vs nurture when it comes to whether you’re a night owl or an early bird. And we talk about how things could change with work and lifestyles to make it easier to live in accordance with our biological rhythms.

Show notes

3:10 – The definition of “upstates” and “downstates”

5:50 – The power of 6 slow, deep breaths per minute to balance the nervous system

9:05 – Watching out for mouth breathing and email apnea

13:30 – Different ways of breathing for different goals

16:35 – Body rhythms – what is heart rate variability and why is it so important?

21:05 – Are you naturally a morning or night person? Nature vs nurture

27:10 – The perfect storm that gets in the way of following our circadian rhythms

29:15 – The evolution of our pre-bedtime downstates – why it's important to check in with your cave mates

30:10 – The culture shift needed for more people to follow their circadian rhythms and improve their health

35:10 – Employers and communities can build downstates into daily work and life

38:15 – Choosing how we react to the world

41:00 – Being smarter about peak performance

45:09 – The science of pacing yourself for long-term productivity

49:42 – The science of light exposure for circadian rhythms

52:20 – Where to learn more about Sara Mednick’s research and writing

Links:

Sara Mednick’s website https://www.saramednick.com/ and her Twitter

Mednick’s recent book - The Power of the Downstate

Mednick’s book on the benefits of napping - Take a Nap! Change Your Life

The blue light blocking glasses recommended in Mednick’s book https://www.amazon.com/dp/B019C3O2UE?psc=1&ref=ppx_yo2ov_dt_b_product_details

An app for measuring heart rate variability - Elite HRV app https://elitehrv.com/

Thorne take-home Melatonin test