How a Deadly Fire Gave Birth to Modern Medicine

The Cocoanut Grove fire in Boston in 1942 tragically claimed 490 lives, but was the catalyst for several important medical advances.

On the evening of November 28, 1942, more than 1,000 revelers from the Boston College-Holy Cross football game jammed into the Cocoanut Grove, Boston's oldest nightclub. When a spark from faulty wiring accidently ignited an artificial palm tree, the packed nightspot, which was only designed to accommodate about 500 people, was quickly engulfed in flames. In the ensuing panic, hundreds of people were trapped inside, with most exit doors locked. Bodies piled up by the only open entrance, jamming the exits, and 490 people ultimately died in the worst fire in the country in forty years.

"People couldn't get out," says Dr. Kenneth Marshall, a retired plastic surgeon in Boston and president of the Cocoanut Grove Memorial Committee. "It was a tragedy of mammoth proportions."

Within a half an hour of the start of the blaze, the Red Cross mobilized more than five hundred volunteers in what one newspaper called a "Rehearsal for Possible Blitz." The mayor of Boston imposed martial law. More than 300 victims—many of whom subsequently died--were taken to Boston City Hospital in one hour, averaging one victim every eleven seconds, while Massachusetts General Hospital admitted 114 victims in two hours. In the hospitals, 220 victims clung precariously to life, in agonizing pain from massive burns, their bodies ravaged by infection.

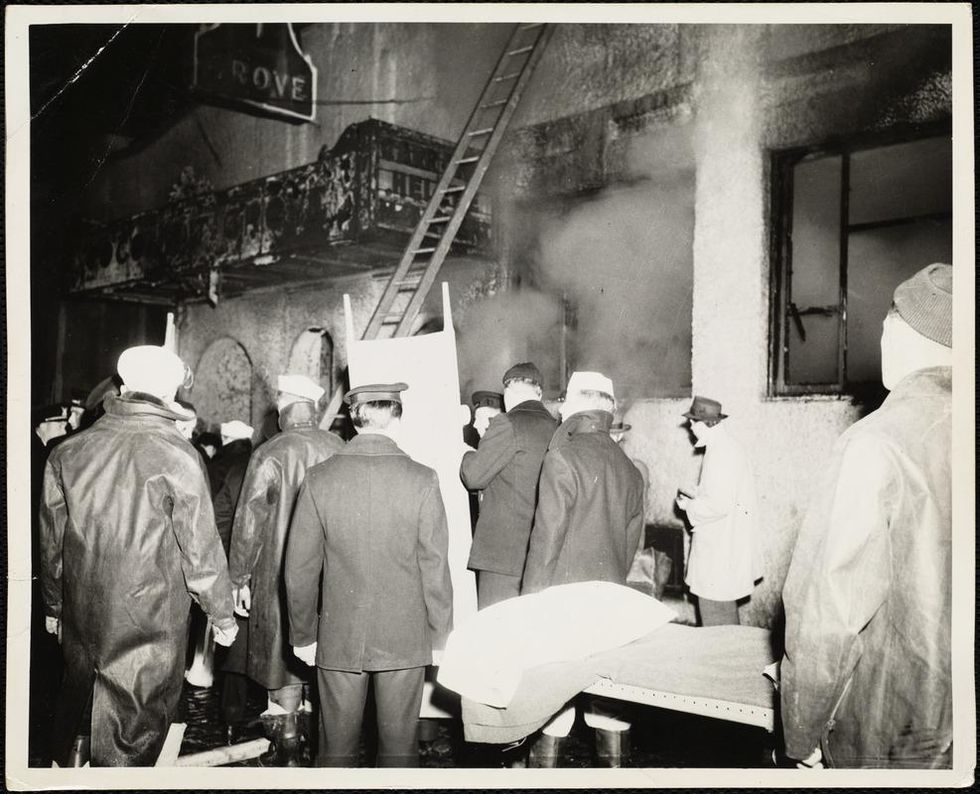

The scene of the fire.

Boston Public Library

Tragic Losses Prompted Revolutionary Leaps

But there is a silver lining: this horrific disaster prompted dramatic changes in safety regulations to prevent another catastrophe of this magnitude and led to the development of medical techniques that eventually saved millions of lives. It transformed burn care treatment and the use of plasma on burn victims, but most importantly, it introduced to the public a new wonder drug that revolutionized medicine, midwifed the birth of the modern pharmaceutical industry, and nearly doubled life expectancy, from 48 years at the turn of the 20th century to 78 years in the post-World War II years.

The devastating grief of the survivors also led to the first published study of post-traumatic stress disorder by pioneering psychiatrist Alexandra Adler, daughter of famed Viennese psychoanalyst Alfred Adler, who was a student of Freud. Dr. Adler studied the anxiety and depression that followed this catastrophe, according to the New York Times, and "later applied her findings to the treatment World War II veterans."

Dr. Ken Marshall is intimately familiar with the lingering psychological trauma of enduring such a disaster. His mother, an Irish immigrant and a nurse in the surgical wards at Boston City Hospital, was on duty that cold Thanksgiving weekend night, and didn't come home for four days. "For years afterward, she'd wake up screaming in the middle of the night," recalls Dr. Marshall, who was four years old at the time. "Seeing all those bodies lined up in neat rows across the City Hospital's parking lot, still in their evening clothes. It was always on her mind and memories of the horrors plagued her for the rest of her life."

The sheer magnitude of casualties prompted overwhelmed physicians to try experimental new procedures that were later successfully used to treat thousands of battlefield casualties. Instead of cutting off blisters and using dyes and tannic acid to treat burned tissues, which can harden the skin, they applied gauze coated with petroleum jelly. Doctors also refined the formula for using plasma--the fluid portion of blood and a medical technology that was just four years old--to replenish bodily liquids that evaporated because of the loss of the protective covering of skin.

"Every war has given us a new medical advance. And penicillin was the great scientific advance of World War II."

"The initial insult with burns is a loss of fluids and patients can die of shock," says Dr. Ken Marshall. "The scientific progress that was made by the two institutions revolutionized fluid management and topical management of burn care forever."

Still, they could not halt the staph infections that kill most burn victims—which prompted the first civilian use of a miracle elixir that was being secretly developed in government-sponsored labs and that ultimately ushered in a new age in therapeutics. Military officials quickly realized this disaster could provide an excellent natural laboratory to test the effectiveness of this drug and see if it could be used to treat the acute traumas of combat in this unfortunate civilian approximation of battlefield conditions. At the time, the very existence of this wondrous medicine—penicillin—was a closely guarded military secret.

From Forgotten Lab Experiment to Wonder Drug

In 1928, Alexander Fleming discovered the curative powers of penicillin, which promised to eradicate infectious pathogens that killed millions every year. But the road to mass producing enough of the highly unstable mold was littered with seemingly unsurmountable obstacles and it remained a forgotten laboratory curiosity for over a decade. But Fleming never gave up and penicillin's eventual rescue from obscurity was a landmark in scientific history.

In 1940, a group at Oxford University, funded in part by the Rockefeller Foundation, isolated enough penicillin to test it on twenty-five mice, which had been infected with lethal doses of streptococci. Its therapeutic effects were miraculous—the untreated mice died within hours, while the treated ones played merrily in their cages, undisturbed. Subsequent tests on a handful of patients, who were brought back from the brink of death, confirmed that penicillin was indeed a wonder drug. But Britain was then being ravaged by the German Luftwaffe during the Blitz, and there were simply no resources to devote to penicillin during the Nazi onslaught.

In June of 1941, two of the Oxford researchers, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, embarked on a clandestine mission to enlist American aid. Samples of the temperamental mold were stored in their coats. By October, the Roosevelt Administration had recruited four companies—Merck, Squibb, Pfizer and Lederle—to team up in a massive, top-secret development program. Merck, which had more experience with fermentation procedures, swiftly pulled away from the pack and every milligram they produced was zealously hoarded.

After the nightclub fire, the government ordered Merck to dispatch to Boston whatever supplies of penicillin that they could spare and to refine any crude penicillin broth brewing in Merck's fermentation vats. After working in round-the-clock relays over the course of three days, on the evening of December 1st, 1942, a refrigerated truck containing thirty-two liters of injectable penicillin left Merck's Rahway, New Jersey plant. It was accompanied by a convoy of police escorts through four states before arriving in the pre-dawn hours at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dozens of people were rescued from near-certain death in the first public demonstration of the powers of the antibiotic, and the existence of penicillin could no longer be kept secret from inquisitive reporters and an exultant public. The next day, the Boston Globe called it "priceless" and Time magazine dubbed it a "wonder drug."

Within fourteen months, penicillin production escalated exponentially, churning out enough to save the lives of thousands of soldiers, including many from the Normandy invasion. And in October 1945, just weeks after the Japanese surrender ended World War II, Alexander Fleming, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain were awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine. But penicillin didn't just save lives—it helped build some of the most innovative medical and scientific companies in history, including Merck, Pfizer, Glaxo and Sandoz.

"Every war has given us a new medical advance," concludes Marshall. "And penicillin was the great scientific advance of World War II."

Opioid prescription policies may hurt those in chronic pain

Guidelines aim to prevent opioid-related deaths by making it more challenging to get prescriptions, but they can also block access for those who desperately need them.

Tinu Abayomi-Paul works as a writer and activist, plus one unwanted job: Trying to fill her opioid prescription. She says that some pharmacists laugh and tell her that no one needs the amount of pain medication that she is seeking. Another pharmacist near her home in Venus, Tex., refused to fill more than seven days of a 30-day prescription.

To get a new prescription—partially filled opioid prescriptions can’t be dispensed later—Abayomi-Paul needed to return to her doctor’s office. But without her medication, she was having too much pain to travel there, much less return to the pharmacy. She rationed out the pills over several weeks, an agonizing compromise that left her unable to work, interact with her children, sleep restfully, or leave the house. “Don’t I deserve to do more than survive?” she says.

Abayomi-Paul’s pain results from a degenerative spine disorder, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and more than a dozen other diagnoses and disabilities. She is part of a growing group of people with chronic pain who have been negatively impacted by the fallout from efforts to prevent opioid overdose deaths.

Guidelines for dispensing these pills are complicated because many opioids, like codeine, oxycodone, and morphine, are prescribed legally for pain. Yet, deaths from opioids have increased rapidly since 1999 and become a national emergency. Many of them, such as heroin, are used illegally. The CDC identified three surges in opioid use: an increase in opioid prescriptions in the ‘90s, a surge of heroin around 2010, and an influx of fentanyl and other powerful synthetic opioids in 2013.

As overdose deaths grew, so did public calls to address them, prompting the CDC to change its prescription guidelines in 2016. The new guidelines suggested limiting medication for acute pain to a seven-day supply, capping daily doses of morphine, and other restrictions. Some statistics suggest that these policies have worked; from 2016 to 2019, prescriptions for opiates fell 44 percent. Physicians also started progressively lowering opioid doses for patients, a practice called tapering. A study tracking nearly 100,000 Medicare subscribers on opioids found that about 13 percent of patients were tapering in 2012, and that number increased to about 23 percent by 2017.

But some physicians may be too aggressive with this tapering strategy. About one in four people had doses reduced by more than 10 percent per week, a rate faster than the CDC recommends. The approach left people like Abayomi-Paul without the medication they needed. Every year, Abayomi-Paul says, her prescriptions are harder to fill. David Brushwood, a pharmacy professor who specializes in policy and outcomes at the University of Florida in Gainesville, says opioid dosing isn’t one-size-fits-all. “Patients need to be taken care of individually, not based on what some government agency says they need,” he says.

‘This is not survivable’

Health policy and disability rights attorney Erin Gilmer advocated for people with pain, using her own experience with chronic pain and a host of medical conditions as a guidepost. She launched an advocacy website, Healthcare as a Human Right, and shared her struggles on Twitter: “This pain is more than anything I've endured before and I've already been through too much. Yet because it's not simply identified no one believes it's as bad as it is. This is not survivable.”

When her pain dramatically worsened midway through 2021, Gilmer’s posts grew ominous: “I keep thinking it can't possibly get worse but somehow every day is worse than the last.”

The CDC revised its guidelines in 2022 after criticisms that people with chronic pain were being undertreated, enduring dangerous withdrawal symptoms, and suffering psychological distress. (Long-term opioid use can cause physical dependency, an adaptive reaction that is different than the compulsive misuse associated with a substance use disorder.) It was too late for Gilmer. On July 7, 2021, the 38-year-old died by suicide.

Last August, an Ohio district court ruling set forth a new requirement for Walgreens, Walmart, and CVS pharmacists in two counties. These pharmacists must now document opioid prescriptions that are turned down, even for customers who have no previous purchases at that pharmacy, and they’re required to share this information with other locations in the same chain. None of the three pharmacies responded to an interview request from Leaps.org.

In a practice called red flagging, pharmacists may label a prescription suspicious for a variety of reasons, such as if a pharmacist observes an unusually high dose, a long distance from the patient’s home to the pharmacy, or cash payment. Pharmacists may question patients or prescribers to resolve red flags but, regardless of the explanation, they’re free to refuse to fill a prescription.

As the risk of litigation has grown, so has finger-pointing, says Seth Whitelaw, a compliance consultant at Whitelaw Compliance Group in West Chester, PA, who advises drug, medical device, and biotech companies. Drugmakers accused in National Prescription Opioid Litigation (NPOL), a complex set of thousands of cases on opioid epidemic deaths, which includes the Ohio district case, have argued that they shouldn’t be responsible for the large supply of opiates and overdose deaths. Yet, prosecutors alleged that these pharmaceutical companies hid addiction and overdose risks when labeling opioids, while distributors and pharmacists failed to identify suspicious orders or scripts.

Patients and pharmacists fear red flags

The requirements that pharmacists document prescriptions they refuse to fill so far only apply to two counties in Ohio. But Brushwood fears they will spread because of this precedent, and because there’s no way for pharmacists to predict what new legislation is on the way. “There is no definition of a red flag, there are no lists of red flags. There is no instruction on what to do when a red flag is detected. There’s no guidance on how to document red flags. It is a standardless responsibility,” Brushwood says. This adds trepidation for pharmacists—and more hoops to jump through for patients.

“I went into the doctor one day here and she said, ‘I'm going to stop prescribing opioids to all my patients effective immediately,” Nicolson says.

“We now have about a dozen studies that show that actually ripping somebody off their medication increases their risk of overdose and suicide by three to five times, destabilizes their health and mental health, often requires some hospitalization or emergency care, and can cause heart attacks,” says Kate Nicolson, founder of the National Pain Advocacy Center based in Boulder, Colorado. “It can kill people.” Nicolson was in pain for decades due to a surgical injury to the nerves leading to her spinal cord before surgeries fixed the problem.

Another issue is that primary care offices may view opioid use as a reason to turn down new patients. In a 2021 study, secret shoppers called primary care clinics in nine states, identifying themselves as long-term opioid users. When callers said their opioids were discontinued because their former physician retired, as opposed to an unspecified reason, they were more likely to be offered an appointment. Even so, more than 40 percent were refused an appointment. The study authors say their findings suggest that some physicians may try to avoid treating people who use opioids.

Abayomi-Paul says red flagging has changed how she fills prescriptions. “Once I go to one place, I try to [continue] going to that same place because of the amount of records that I have and making sure my medications don’t conflict,” Abayomi-Paul says.

Nicolson moved to Colorado from Washington D.C. in 2015, before the CDC issued its 2016 guidelines. When the guidelines came out, she found the change to be shockingly abrupt. “I went into the doctor one day here and she said, ‘I'm going to stop prescribing opioids to all my patients effective immediately.’” Since then, she’s spoken with dozens of patients who have been red-flagged or simply haven’t been able to access pain medication.

Despite her expertise, Nicolson isn’t positive she could successfully fill an opioid prescription today even if she needed one. At this point, she’s not sure exactly what various pharmacies would view as a red flag. And she’s not confident that these red flags even work. “You can have very legitimate reasons for being 50 miles away or having to go to multiple pharmacies, given that there are drug shortages now, as well as someone refusing to fill [a prescription.] It doesn't mean that you’re necessarily ‘drug seeking.’”

While there’s no easy solution. Whitelaw says clarifying the role of pharmacists and physicians in patient access to opioids could help people get the medication they need. He is seeking policy changes that focus on the needs of people in pain more than the number of prescriptions filled. He also advocates standardizing the definition of red flags and procedures for resolving them. Still, there will never be a single policy that can be applied to all people, explains Brushwood, the University of Florida professor. “You have to make a decision about each individual prescription.”

Recent immigration restrictions have left many foreign researchers' projects and careers in limbo—and some in jeopardy.

This article is part of the magazine, "The Future of Science In America: The Election Issue," co-published by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD.

When COVID-19 cases were surging in New York City in early spring, Chitra Mohan, a postdoctoral fellow at Weill Cornell, was overwhelmed with worry. But the pandemic was only part of her anxieties. Having come to the United States from India on a student visa that allowed her to work for a year after completing her degree, she had applied for a two-year extension, typically granted for those in STEM fields. But due to a clerical error—Mohan used an electronic signatureinstead of a handwritten one— her application was denied and she could no longerwork in the United States.

"I was put on unpaid leave and I lost my apartment and my health insurance—and that was in the middle of COVID!" she says.

Meanwhile her skills were very much needed in those unprecedented times. A molecular biologist studying how DNA can repair itself, Mohan was trained in reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction or RT-PCR—a lab technique that detects pathogens and is used to diagnose COVID-19. Mohan wanted to volunteer at testing centers, but because she couldn't legally work in the U.S., she wasn't allowed to help either. She moved to her cousin's house, hired a lawyer, and tried to restore her work status.

"I spent about $4,000 on lawyer fees and another $1,200 to pay for the motions I filed," she recalls. "I had to borrow money from my parents and my cousin because without my salary I just didn't have the $7,000 at hand." But the already narrow window of opportunity slammed completely shut when the Trump administration suspended issuing new visas for foreign researchers in June. All Mohan's attempts were denied. In August, she had to leave the country. "Given the recent work visa ban by the administration, all my options in the U.S. are closed," she wrote a bitter note on Twitter. "I have to uproot my entire life in NY for the past 6 years and leave." She eventually found a temporary position in Calcutta, where she can continue research.

Mohan is hardly alone in her visa saga. Many foreign scholars on H- and J-type visas and other permits that let them remain employed in America had been struggling to keep their rights to continue research, which in certain cases is crucial to battling the pandemic. Some had to leave the country, some filed every possible extension to buy time, and others are stuck in their home countries, unable to return. The already cumbersome process of applying for visas and extensions became crippled during the lockdowns. But in June, when President Trump extended and expanded immigration restrictions to cut the number of immigrant workers entering the U.S., the new limits left researchers' projects and careers in limbo—and some in jeopardy.

"We have been a beneficiary of this flow of human capacity and resource investment for many generations—and this is now threatened."

Rakesh Ramachandran, whose computational biology work contributed to one of the first coronavirus studies to map out its protein structures—is stranded in India. In early March, he had travelled there to attend a conference and visit the American consulate to stamp his H1 visa for a renewal, already granted. The pandemic shut down both the conference and the consulates, and Ramachandran hasn't been able to come back since. The consulates finally opened in September, but so far the online portal has no available appointment slots. "I'm told to keep trying," Ramachandran says.

The visa restrictions affected researchers worldwide, regardless of disciplines or countries. A Ph.D. student in neuroscience, Morgane Leroux had to do her experiments with mice at Gladstone Institutes in America and analyze the data back home at Sorbonne University in France. She had finished her first round of experiments when the lockdowns forced her to return to Paris, and she hasn't been able to come back to resume her work since. "I can't continue the experiments, which is really frustrating," she says, especially because she doesn't know what it means for her Ph.D. "I may have to entirely change my subject," she says, which she doesn't want to do—it would be a waste of time and money.

But besides wreaking havoc in scholars' personal lives and careers, the visa restrictions had—and will continue to have—tremendous deleterious effects on America's research and its global scientific competitiveness. "It's incredibly short-sighted and self-destructing to restrict the immigration of scientists into the U.S.," says Benjamin G. Neel, who directs the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center at New York University. "If they can't come here, they will go elsewhere," he says, causing a brain drain.

Neel in his lab with postdocs

(Courtesy of Neel)

Neel felt the outcomes of the shortsighted policies firsthand. In the past few months, his lab lost two postdoctoral researchers who had made major strides in understanding the biology of several particularly stubborn, treatment-resistant malignancies. One postdoc studied the underlying mechanisms responsible for 90 percent of pancreatic cancers and half of the colon ones. The other one devised a new system of modeling ovarian cancer in mice to test new therapeutic drug combinations for the deadliest tumor types—but had to return home to China.

"By working around the clock, she was able to get her paper accepted, but she hasn't been able to train us to use this new system, which can set us back six months," Neel says.

Her discoveries also helped the lab secure about $900,000 in grants for new research. Losing people like this is "literally killing the goose that lays the golden eggs," Neel adds. "If you want to make America poor again, this is the way to do it."

Cassidy R. Sugimoto at Indiana University Bloomington, who studies how scientific knowledge is produced and disseminated, says that scientists are the most productive when they are free to move, exchange ideas, and work at labs with the best equipment. Restricting that freedom reduces their achievement.

"Several empirical studied demonstrated the benefits to the U.S. by attracting and retaining foreign scientists. The disproportional number of our Nobel Prize winners were not only foreign-born but also foreign-educated," she says. Scientific advancement bolsters the country's economic prowess, too, so turning scholars away is bad for the economy long-term. "We have been a beneficiary of this flow of human capacity and resource investment for many generations—and this is now threatened," Sugimoto adds—because scientists will look elsewhere. "We are seeing them shifting to other countries that are more hospitable, both ideologically and in terms of health security. Many visiting scholars, postdocs, and graduate students who would otherwise come to the United States are now moving to Canada."

It's not only the Ph.D. students and postdocs who are affected. In some cases, even well-established professors who have already made their marks in the field and direct their own labs at prestigious research institutions may have to pack up and leave the country in the next few months. One scientist who directs a prominent neuroscience lab is betting on his visa renewal and a green card application, but if that's denied, the entire lab may be in jeopardy, as many grants hinge on his ability to stay employed in America.

"It's devastating to even think that it can happen," he says—after years of efforts invested. "I can't even comprehend how it would feel. It would be terrifying and really sad." (He asked to withhold his name for fear that it may adversely affect his applications.) Another scientist who originally shared her story for this article, later changed her mind and withdrew, worrying that speaking out may hurt the entire project, a high-profile COVID-19 effort. It's not how things should work in a democratic country, scientists admit, but that's the reality.

Still, some foreign scholars are speaking up. Mehmet Doğan, a physicist at University of California Berkeley who has been fighting a visa extension battle all year, says it's important to push back in an organized fashion with petitions and engage legislators. "This administration was very creative in finding subtle and not so subtle ways to make our lives more difficult," Doğan says. He adds that the newest rules, proposed by the Department of Homeland Security on September 24, could further limit the time scholars can stay, forcing them into continuous extension battles. That's why the upcoming election might be a turning point for foreign academics. "This election will decide if many of us will see the U.S. as the place to stay and work or whether we look at other countries," Doğan says, echoing the worries of Neel, Sugimoto, and others in academia.

Dogan on Zoom talking to his fellow union members of the Academic Researchers United, a union of almost 5,000 Academic Researchers.

(Credit: Ceyda Durmaz Dogan)

If this year has shown us anything, it is that viruses and pandemics know no borders as they sweep across the globe. Likewise, science can't be restrained by borders either. "Science is an international endeavor," says Neel—and right now humankind now needs unified scientific research more than ever, unhindered by immigration hurdles and visa wars. Humanity's wellbeing in America and beyond depends on it.

[Editor's Note: To read other articles in this special magazine issue, visit the beautifully designed e-reader version.]

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.