How a Deadly Fire Gave Birth to Modern Medicine

The Cocoanut Grove fire in Boston in 1942 tragically claimed 490 lives, but was the catalyst for several important medical advances.

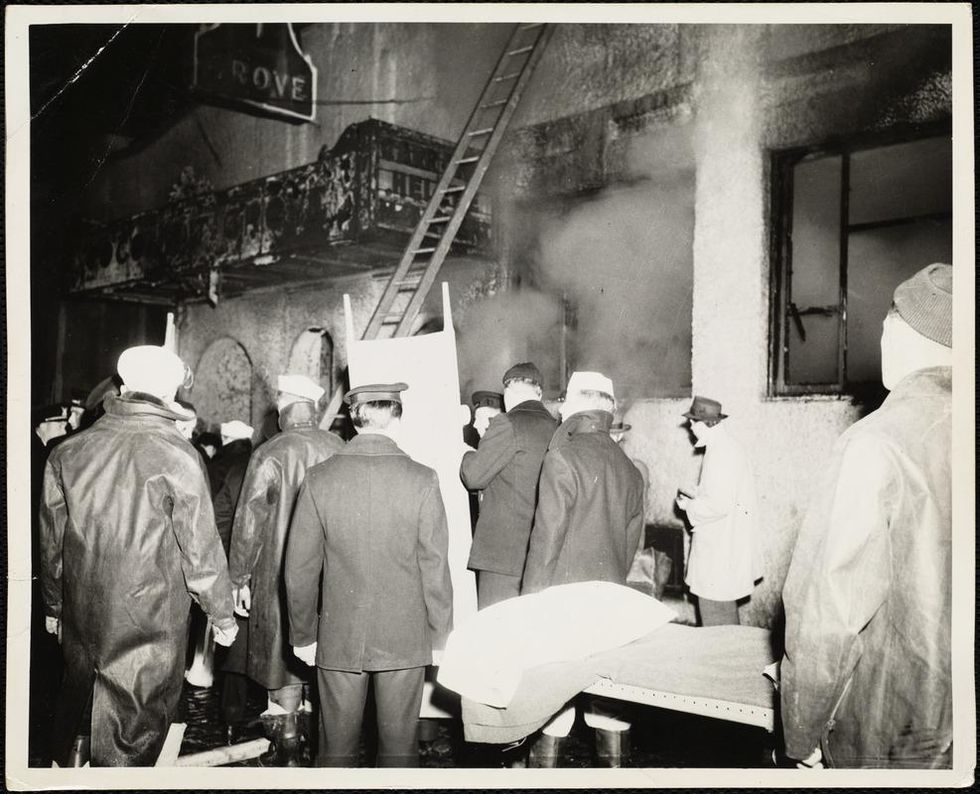

On the evening of November 28, 1942, more than 1,000 revelers from the Boston College-Holy Cross football game jammed into the Cocoanut Grove, Boston's oldest nightclub. When a spark from faulty wiring accidently ignited an artificial palm tree, the packed nightspot, which was only designed to accommodate about 500 people, was quickly engulfed in flames. In the ensuing panic, hundreds of people were trapped inside, with most exit doors locked. Bodies piled up by the only open entrance, jamming the exits, and 490 people ultimately died in the worst fire in the country in forty years.

"People couldn't get out," says Dr. Kenneth Marshall, a retired plastic surgeon in Boston and president of the Cocoanut Grove Memorial Committee. "It was a tragedy of mammoth proportions."

Within a half an hour of the start of the blaze, the Red Cross mobilized more than five hundred volunteers in what one newspaper called a "Rehearsal for Possible Blitz." The mayor of Boston imposed martial law. More than 300 victims—many of whom subsequently died--were taken to Boston City Hospital in one hour, averaging one victim every eleven seconds, while Massachusetts General Hospital admitted 114 victims in two hours. In the hospitals, 220 victims clung precariously to life, in agonizing pain from massive burns, their bodies ravaged by infection.

The scene of the fire.

Boston Public Library

Tragic Losses Prompted Revolutionary Leaps

But there is a silver lining: this horrific disaster prompted dramatic changes in safety regulations to prevent another catastrophe of this magnitude and led to the development of medical techniques that eventually saved millions of lives. It transformed burn care treatment and the use of plasma on burn victims, but most importantly, it introduced to the public a new wonder drug that revolutionized medicine, midwifed the birth of the modern pharmaceutical industry, and nearly doubled life expectancy, from 48 years at the turn of the 20th century to 78 years in the post-World War II years.

The devastating grief of the survivors also led to the first published study of post-traumatic stress disorder by pioneering psychiatrist Alexandra Adler, daughter of famed Viennese psychoanalyst Alfred Adler, who was a student of Freud. Dr. Adler studied the anxiety and depression that followed this catastrophe, according to the New York Times, and "later applied her findings to the treatment World War II veterans."

Dr. Ken Marshall is intimately familiar with the lingering psychological trauma of enduring such a disaster. His mother, an Irish immigrant and a nurse in the surgical wards at Boston City Hospital, was on duty that cold Thanksgiving weekend night, and didn't come home for four days. "For years afterward, she'd wake up screaming in the middle of the night," recalls Dr. Marshall, who was four years old at the time. "Seeing all those bodies lined up in neat rows across the City Hospital's parking lot, still in their evening clothes. It was always on her mind and memories of the horrors plagued her for the rest of her life."

The sheer magnitude of casualties prompted overwhelmed physicians to try experimental new procedures that were later successfully used to treat thousands of battlefield casualties. Instead of cutting off blisters and using dyes and tannic acid to treat burned tissues, which can harden the skin, they applied gauze coated with petroleum jelly. Doctors also refined the formula for using plasma--the fluid portion of blood and a medical technology that was just four years old--to replenish bodily liquids that evaporated because of the loss of the protective covering of skin.

"Every war has given us a new medical advance. And penicillin was the great scientific advance of World War II."

"The initial insult with burns is a loss of fluids and patients can die of shock," says Dr. Ken Marshall. "The scientific progress that was made by the two institutions revolutionized fluid management and topical management of burn care forever."

Still, they could not halt the staph infections that kill most burn victims—which prompted the first civilian use of a miracle elixir that was being secretly developed in government-sponsored labs and that ultimately ushered in a new age in therapeutics. Military officials quickly realized this disaster could provide an excellent natural laboratory to test the effectiveness of this drug and see if it could be used to treat the acute traumas of combat in this unfortunate civilian approximation of battlefield conditions. At the time, the very existence of this wondrous medicine—penicillin—was a closely guarded military secret.

From Forgotten Lab Experiment to Wonder Drug

In 1928, Alexander Fleming discovered the curative powers of penicillin, which promised to eradicate infectious pathogens that killed millions every year. But the road to mass producing enough of the highly unstable mold was littered with seemingly unsurmountable obstacles and it remained a forgotten laboratory curiosity for over a decade. But Fleming never gave up and penicillin's eventual rescue from obscurity was a landmark in scientific history.

In 1940, a group at Oxford University, funded in part by the Rockefeller Foundation, isolated enough penicillin to test it on twenty-five mice, which had been infected with lethal doses of streptococci. Its therapeutic effects were miraculous—the untreated mice died within hours, while the treated ones played merrily in their cages, undisturbed. Subsequent tests on a handful of patients, who were brought back from the brink of death, confirmed that penicillin was indeed a wonder drug. But Britain was then being ravaged by the German Luftwaffe during the Blitz, and there were simply no resources to devote to penicillin during the Nazi onslaught.

In June of 1941, two of the Oxford researchers, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, embarked on a clandestine mission to enlist American aid. Samples of the temperamental mold were stored in their coats. By October, the Roosevelt Administration had recruited four companies—Merck, Squibb, Pfizer and Lederle—to team up in a massive, top-secret development program. Merck, which had more experience with fermentation procedures, swiftly pulled away from the pack and every milligram they produced was zealously hoarded.

After the nightclub fire, the government ordered Merck to dispatch to Boston whatever supplies of penicillin that they could spare and to refine any crude penicillin broth brewing in Merck's fermentation vats. After working in round-the-clock relays over the course of three days, on the evening of December 1st, 1942, a refrigerated truck containing thirty-two liters of injectable penicillin left Merck's Rahway, New Jersey plant. It was accompanied by a convoy of police escorts through four states before arriving in the pre-dawn hours at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dozens of people were rescued from near-certain death in the first public demonstration of the powers of the antibiotic, and the existence of penicillin could no longer be kept secret from inquisitive reporters and an exultant public. The next day, the Boston Globe called it "priceless" and Time magazine dubbed it a "wonder drug."

Within fourteen months, penicillin production escalated exponentially, churning out enough to save the lives of thousands of soldiers, including many from the Normandy invasion. And in October 1945, just weeks after the Japanese surrender ended World War II, Alexander Fleming, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain were awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine. But penicillin didn't just save lives—it helped build some of the most innovative medical and scientific companies in history, including Merck, Pfizer, Glaxo and Sandoz.

"Every war has given us a new medical advance," concludes Marshall. "And penicillin was the great scientific advance of World War II."

Debates over transgender athletes rage on, with new state bans and rules for Olympians, NCAA sports

Some argue that transgender females should be banned from competing with women in sports, while others think such bans are unfair, as the NCAA and other organizations try to keep up with research on how testosterone affects performance.

Ashley O’Connor, who was biologically male at birth but identifies as female, decided to compete in badminton as a girl during her senior year of high school in Downers Grove, Illinois. There was no team for boys, and a female friend and badminton player “practically bullied me into joining” the girls’ team. O’Connor, who is 18 and taking hormone replacement therapy for her gender transition, recalled that “it was easily one of the best decisions I have ever made.”

She believes there are many reasons why it’s important for transgender people to have the option of playing sports on the team of their choice. “It provides a sense of community,” said O’Connor, now a first-year student concentrating in psychology at the College of DuPage in Glen Ellyn, Illinois.

“It’s a great way to get a workout, which is good for physical and mental health,” she added. She also enjoyed the opportunity to be competitive, learn about her strengths and weaknesses, and just be normal. “Trans people have friends and trans people want to play sports with their friends, especially in adolescence,” she said.

However, in 18 states, many of which are politically conservative, laws prohibit transgender students from participating in sports consistent with their gender identity, according to the Movement Advancement Project, an independent, nonprofit think tank based in Boulder, Colo., that focuses on the rights of LGBTQ people. The first ban was passed in Idaho in 2020, although federal district judges have halted this legislation and a similar law in West Virginia from taking effect.

Proponents of the bans caution that transgender females would have an unfair biological advantage in competitive school sports with other girls or women as a result of being born as stronger males, potentially usurping the athletic accomplishments of other athletes.

“The future of women’s sports is at risk, and the equal rights of female athletes is being infringed,” said Penny Nance, CEO and president of Concerned Women for America, a legislative action committee in D.C. that seeks to impact culture to promote religious values.

“As the tidal wave of gender activism consumes sports from the Olympics on down, a backlash is being felt as parents are furious about the disregard for their daughters who have worked very hard to achieve success as athletes,” Nance added. “Former athletes, whose records are being shattered, are demanding answers.”

Meanwhile, opponents of the bans contend that they bar transgender athletes from playing sports with friends and learning the value of teamwork and other life lessons. These laws target transgender girls most often in kindergarten through high school but sometimes in college as well. Many local schools and state athletic associations already have their own guidelines “to both protect transgender people and ensure a level playing field for all athletes,” according to the Movement Advancement Project’s website. But statewide bans take precedence over these policies.

"It’s easy to sympathize on some level with arguments on both sides, and it’s likely going to be impossible to make everyone happy,” said Liz Joy, a past president of the American College of Sports Medicine.

In January, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), based in Indianapolis, tried to sort out the controversy by implementing a new policy. It requires transgender students participating in female sports to prove that they’ve been taking treatments to suppress testosterone for at least one year before competition, as well as demonstrating that their testosterone level is sufficiently low, depending on the sport, through a blood test.

Then, in August, the NCAA clarified that these athletes also must take another blood test six months after their season has started that shows their testosterone levels aren’t too high. Additional guidelines will take effect next August.

Even with these requirements, “there is no plan that is going to be considered equitable and fair to all,” said Bradley Anawalt, an endocrinologist at the University of Washington School of Medicine. Biologically, he noted, there is still some evidence that a transgender female who initiates hormone therapy with estrogen and drops her testosterone to very low levels may have some advantage over other females, based on characteristics such as hand and foot size, height and perhaps strength.

Liz Joy, a past president of the American College of Sports Medicine, agrees that allowing transgender athletes to compete on teams of their self-identifying gender poses challenges. “It’s easy to sympathize on some level with arguments on both sides, and it’s likely going to be impossible to make everyone happy,” said Joy, a physician and senior medical director of wellness and nutrition at Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, Utah. While advocating for inclusion, she added that “sport was incredibly important in my life. I just want everyone to be able to benefit from it.”

One solution may be to allow transgender youth to play sports in a way that aligns with their gender identity until a certain age and before an elite level. “There are minimal or no potential financial stakes for most youth sports before age 13 or 14, and you do not have a lot of separation in athlete performance between most boys and girls until about age 13,” said Anwalt, who was a reviewer of the Endocrine Society’s national guidelines on transgender care.

Myron Genel, a professor emeritus and former chief of pediatric endocrinology at Yale School of Medicine, said it’s difficult to argue that height gives transgender females an edge because in some sports tall women already dominate over their shorter counterparts.

He added that the decision to allow transgender females to compete with other girls or women could hinge on when athletes began taking testosterone blockers. “If the process of conversion from male to female has been undertaken in the early stages of puberty, from my perspective, they have very little unique advantage,” said Genel, who advised the International Olympic Committee (IOC), based in Switzerland, on testosterone limits for transgender athletes.

Because young athletes’ bodies are still developing, “the differences in natural abilities are so massive that they would overwhelm any advantage a transgender athlete might have,” said Thomas H. Murray, president emeritus of The Hastings Center, a pioneering bioethics research institute in Garrison, New York, and author of the book “Good Sport,” which focuses on the ethics and values in the Olympics and other competitions.

“There’s no good reason to limit the participation of transgender athletes in the sports where male athletes don’t have an advantage over women,” such as sailing, archery and shooting events, Murray said. “The burden of proof rests on those who want to restrict participation by transgender athletes. They must show that in this sport, at this level of competition, transgender athletes have a conspicuous advantage.”

Last year, the IOC issued a new framework emphasizing that the Olympic rules related to transgender participation should be specific to each sport. “This is an evolving topic and there has been—as it will continue to be—new research coming out and new developments informing our approach,” and there’s currently no consensus on how testosterone affects performance across all sports, an IOC spokesperson told Leaps.org.

Many of the new laws prohibiting transgender people from competing in sports consistent with their gender identity specifically apply to transgender females. Yet, some experts say the issue also affects transgender males, nonbinary and intersex athletes.

“There has been quite a bit of attention paid to transgender females and their participation in biological female sports and almost minimal focus on transgender male competition in male sports or in any sports,” said Katherine Drabiak, associate professor of public health law and medical ethics at University of South Florida in Tampa. In fact, “transgender men, because they were born female, would be at a disadvantage of having less lean body mass, less strength and less muscular area as a general category compared to a biological male.”

While discussing transgender students’ participation in sports, it’s important to call attention to the toll that anti-transgender legislation can take on these young people’s well-being, said Jonah DeChants, a research scientist at The Trevor Project, a suicide prevention and mental health organization for LGBTQ youth. Recent polling found that 85 percent of transgender and nonbinary youth said that debates around anti-transgender laws had a negative impact on their mental health.

“The reality is simple: Most transgender girls want to play sports for the same reasons as any student—to benefit their health, to have fun, and to build connection with friends,” DeChants said. According to a new peer-reviewed qualitative study by researchers at The Trevor Project, many trans girls who participated in sports experienced harassment and stigma based on their gender identity, which can contribute to poor mental health outcomes and suicide risk.

In addition to badminton, O'Connor played other sports such as volleyball, and she plans to become an assistant coach or manager of her old high school's badminton team.

Ashley O'Connor

However, DeChants added, research also shows that young people who reported living in an accepting community, had access to LGBTQ-affirming spaces, or had social support from family and friends reported significantly lower rates of attempting suicide in the past year. “We urge coaches, educators and school administrators to seek LGBTQ-cultural competency training, implement zero tolerance policies for anti-trans bullying, and create safe, affirming environments for all transgender students on and off the field,” DeChants said.

O’Connor said her experiences on the athletic scene have been mostly positive. The politics of her community lean somewhat liberal, and she thinks it’s probably more supportive than some other areas of the country, though she noted the local library has received threats for hosting LGBTQ events. In addition to badminton, she also played baseball, lacrosse, volleyball, basketball and hockey. In the spring, she plans to become an assistant coach or manager for the girls’ badminton team at her old high school.

“When I played badminton, I never got any direct backlash from any coaches, competitors or teammates,” she said. “I had a few other teammates that identified as trans or nonbinary, [and] nearly all of the people I ever interacted with were super pleasant and treated me like any other normal person.” She added that transgender athletes “have aspirations. We have wants and needs. We have dreams. And at the end of the day, we just want to live our lives and be happy like everyone else.”

In this week's Friday Five, research on a "smart" bandage for wounds, a breakthrough in fighting inflammation, the pros and cons of a new drug for Alzheimer's, benefits of the Mediterranean diet with a twist, and we've learned to recycle a plastic that was un-recyclable.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- Research on a "smart" bandage for wounds

- A breakthrough in fighting inflammation

- The pros and cons of a new drug for Alzheimer's

- Benefits of the Mediterranean diet - with a twist

- How to recycle a plastic that was un-recyclable