Pregnant & Breastfeeding Women Who Get the COVID-19 Vaccine Are Protecting Their Infants, Research Suggests

Becky Cummings, who got vaccinated in December, snuggles her newborn, Clark, while he takes a nap.

Becky Cummings had multiple reasons to get vaccinated against COVID-19 while tending to her firstborn, Clark, who arrived in September 2020 at 27 weeks.

The 29-year-old intensive care unit nurse in Greensboro, North Carolina, had witnessed the devastation day in and day out as the virus took its toll on the young and old. But when she was offered the vaccine, she hesitated, skeptical of its rapid emergency use authorization.

Exclusion of pregnant and lactating mothers from clinical trials fueled her concerns. Ultimately, though, she concluded the benefits of vaccination outweighed the risks of contracting the potentially deadly virus.

"Long story short," Cummings says, in December "I got vaccinated to protect myself, my family, my patients, and the general public."

At the time, Cummings remained on the fence about breastfeeding, citing a lack of evidence to support its safety after vaccination, so she pumped and stashed breast milk in the freezer. Her son is adjusting to life as a preemie, requiring mother's milk to be thickened with formula, but she's becoming comfortable with the idea of breastfeeding as more research suggests it's safe.

"If I could pop him on the boob," she says, "I would do it in a heartbeat."

Now, a study recently published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found "robust secretion" of specific antibodies in the breast milk of mothers who received a COVID-19 vaccine, indicating a potentially protective effect against infection in their infants.

The presence of antibodies in the breast milk, detectable as early as two weeks after vaccination, lasted for six weeks after the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

"We believe antibody secretion into breast milk will persist for much longer than six weeks, but we first wanted to prove any secretion at all after vaccination," says Ilan Youngster, the study's corresponding author and head of pediatric infectious diseases at Shamir Medical Center in Zerifin, Israel.

That's why the research team performed a preliminary analysis at six weeks. "We are still collecting samples from participants and hope to soon be able to comment about the duration of secretion."

As with other respiratory illnesses, such as influenza and pertussis, secretion of antibodies in breast milk confers protection from infection in infants. The researchers expect a similar immune response from the COVID-19 vaccine and are expecting the findings to spur an increase in vaccine acceptance among pregnant and lactating women.

A COVID-19 outbreak struck three families the research team followed in the study, resulting in at least one non-breastfed sibling developing symptomatic infection; however, none of the breastfed babies became ill. "This is obviously not empirical proof," Youngster acknowledges, "but still a nice anecdote."

Leaps.org inquired whether infants who derive antibodies only through breast milk are likely to have a lower immunity than infants whose mothers were vaccinated while they were in utero. In other words, is maternal transmission of antibodies stronger during pregnancy than during breastfeeding, or about the same?

"This is a different kind of transmission," Youngster explains. "When a woman is infected or vaccinated during pregnancy, some antibodies will be transferred through the placenta to the baby's bloodstream and be present for several months." But in the nursing mother, that protection occurs through local action. "We always recommend breastfeeding whenever possible, and, in this case, it might have added benefits."

A study published online in March found COVID-19 vaccination provided pregnant and lactating women with robust immune responses comparable to those experienced by their nonpregnant counterparts. The study, appearing in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, documented the presence of vaccine-generated antibodies in umbilical cord blood and breast milk after mothers had been vaccinated.

Natali Aziz, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Stanford University School of Medicine, notes that it's too early to draw firm conclusions about the reduction in COVID-19 infection rates among newborns of vaccinated mothers. Citing the two aforementioned research studies, she says it's biologically plausible that antibodies passed through the placenta and breast milk impart protective benefits. While thousands of pregnant and lactating women have been vaccinated against COVID-19, without incurring adverse outcomes, many are still wondering whether it's safe to breastfeed afterward.

It's important to bear in mind that pregnant women may develop more severe COVID-19 complications, which could lead to intubation or admittance to the intensive care unit. "We, in our practice, are supporting pregnant and breastfeeding patients to be vaccinated," says Aziz, who is also director of perinatal infectious diseases at Stanford Children's Health, which has been vaccinating new mothers and other hospitalized patients at discharge since late April.

Earlier in April, Huntington Hospital in Long Island, New York, began offering the COVID-19 vaccine to women after they gave birth. The hospital chose the one-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine for postpartum patients, so they wouldn't need to return for a second shot while acclimating to life with a newborn, says Mitchell Kramer, chairman of obstetrics and gynecology.

The hospital suspended the program when the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention paused use of the J&J vaccine starting April 13, while investigating several reports of dangerous blood clots and low platelet counts among more than 7 million people in the United States who had received that vaccine.

In lifting the pause April 23, the agencies announced the vaccine's fact sheets will bear a warning of the heightened risk for a rare but serious blood clot disorder among women under age 50. As a result, Kramer says, "we will likely not be using the J&J vaccine for our postpartum population."

So, would it make sense to vaccinate infants when one for them eventually becomes available, not just their mothers? "In general, most of the time, infants do not have as good of an immune response to vaccines," says Jonathan Temte, associate dean for public health and community engagement at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison.

"Many of our vaccines are held until children are six months of age. For example, the influenza vaccine starts at age six months, the measles vaccine typically starts one year of age, as do rubella and mumps. Immune response is typically not very good for viral illnesses in young infants under the age of six months."

So far, the FDA has granted emergency use authorization of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for children as young as 16 years old. The agency is considering data from Pfizer to lower that age limit to 12. Studies are also underway in children under age 12. Meanwhile, data from Moderna on 12-to 17-year-olds and from Pfizer on 12- to 15-year-olds have not been made public. (Pfizer announced at the end of March that its vaccine is 100 percent effective in preventing COVID-19 in the latter age group, and FDA authorization for this population is expected soon.)

"There will be step-wise progression to younger children, with infants and toddlers being the last ones tested," says James Campbell, a pediatric infectious diseases physician and head of maternal and child clinical studies at the University of Maryland School of Medicine Center for Vaccine Development.

"Once the data are analyzed for safety, tolerability, optimal dose and regimen, and immune responses," he adds, "they could be authorized and recommended and made available to American children." The data on younger children are not expected until the end of this year, with regulatory authorization possible in early 2022.

For now, Vonnie Cesar, a family nurse practitioner in Smyrna, Georgia, is aiming to persuade expectant and new mothers to get vaccinated. She has observed that patients in metro Atlanta seem more inclined than their rural counterparts.

To quell some of their skepticism and fears, Cesar, who also teaches nursing students, conceived a visual way to demonstrate the novel mechanism behind the COVID-19 vaccine technology. Holding a palm-size physical therapy ball outfitted with clear-colored push pins, she simulates the spiked protein of the coronavirus. Slime slathered at the gaps permeates areas around the spikes—a process similar to how our antibodies build immunity to the virus.

These conversations often lead hesitant patients to discuss vaccination with their husbands or partners. "The majority of people I'm speaking with," she says, "are coming to the conclusion that this is the right thing for me, this is the common good, and they want to make sure that they're here for their children."

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article mistakenly stated that the COVID-19 vaccines were granted emergency "approval." They have been granted emergency use authorization, not full FDA approval. We regret the error.

DNA- and RNA-based electronic implants may revolutionize healthcare

The test tubes contain tiny DNA/enzyme-based circuits, which comprise TRUMPET, a new type of electronic device, smaller than a cell.

Implantable electronic devices can significantly improve patients’ quality of life. A pacemaker can encourage the heart to beat more regularly. A neural implant, usually placed at the back of the skull, can help brain function and encourage higher neural activity. Current research on neural implants finds them helpful to patients with Parkinson’s disease, vision loss, hearing loss, and other nerve damage problems. Several of these implants, such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink, have already been approved by the FDA for human use.

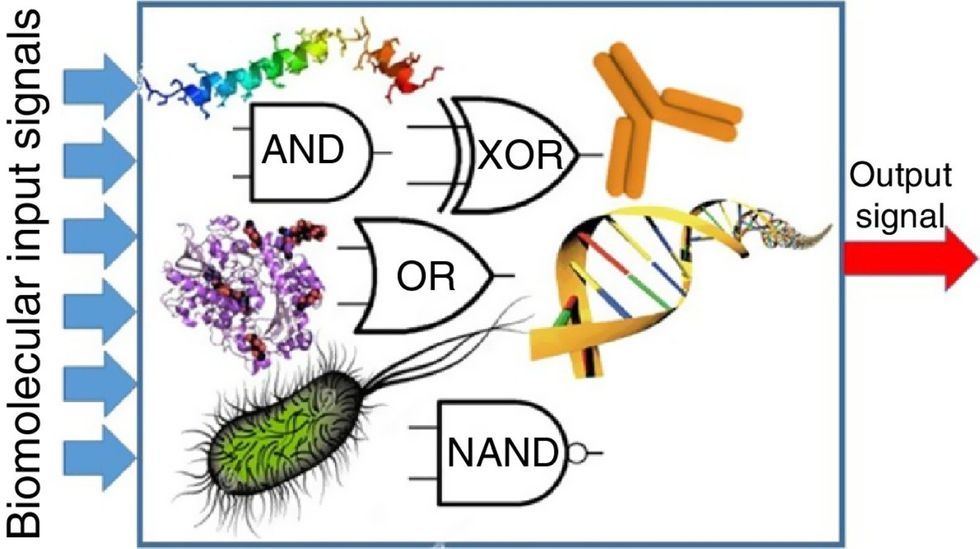

Yet, pacemakers, neural implants, and other such electronic devices are not without problems. They require constant electricity, limited through batteries that need replacements. They also cause scarring. “The problem with doing this with electronics is that scar tissue forms,” explains Kate Adamala, an assistant professor of cell biology at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. “Anytime you have something hard interacting with something soft [like muscle, skin, or tissue], the soft thing will scar. That's why there are no long-term neural implants right now.” To overcome these challenges, scientists are turning to biocomputing processes that use organic materials like DNA and RNA. Other promised benefits include “diagnostics and possibly therapeutic action, operating as nanorobots in living organisms,” writes Evgeny Katz, a professor of bioelectronics at Clarkson University, in his book DNA- And RNA-Based Computing Systems.

While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output.

Adamala’s research focuses on developing such biocomputing systems using DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids. Using these molecules in the biocomputing systems allows the latter to be biocompatible with the human body, resulting in a natural healing process. In a recent Nature Communications study, Adamala and her team created a new biocomputing platform called TRUMPET (Transcriptional RNA Universal Multi-Purpose GatE PlaTform) which acts like a DNA-powered computer chip. “These biological systems can heal if you design them correctly,” adds Adamala. “So you can imagine a computer that will eventually heal itself.”

The basics of biocomputing

Biocomputing and regular computing have many similarities. Like regular computing, biocomputing works by running information through a series of gates, usually logic gates. A logic gate works as a fork in the road for an electronic circuit. The input will travel one way or another, giving two different outputs. An example logic gate is the AND gate, which has two inputs (A and B) and two different results. If both A and B are 1, the AND gate output will be 1. If only A is 1 and B is 0, the output will be 0 and vice versa. If both A and B are 0, the result will be 0. While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output. In this case, the DNA enters the logic gate as a single or double strand.

If the DNA is double-stranded, the system “digests” the DNA or destroys it, which results in non-fluorescence or “0” output. Conversely, if the DNA is single-stranded, it won’t be digested and instead will be copied by several enzymes in the biocomputing system, resulting in fluorescent RNA or a “1” output. And the output for this type of binary system can be expanded beyond fluorescence or not. For example, a “1” output might be the production of the enzyme insulin, while a “0” may be that no insulin is produced. “This kind of synergy between biology and computation is the essence of biocomputing,” says Stephanie Forrest, a professor and the director of the Biodesign Center for Biocomputing, Security and Society at Arizona State University.

Biocomputing circles are made of DNA, RNA, proteins and even bacteria.

Evgeny Katz

The TRUMPET’s promise

Depending on whether the biocomputing system is placed directly inside a cell within the human body, or run in a test-tube, different environmental factors play a role. When an output is produced inside a cell, the cell's natural processes can amplify this output (for example, a specific protein or DNA strand), creating a solid signal. However, these cells can also be very leaky. “You want the cells to do the thing you ask them to do before they finish whatever their businesses, which is to grow, replicate, metabolize,” Adamala explains. “However, often the gate may be triggered without the right inputs, creating a false positive signal. So that's why natural logic gates are often leaky." While biocomputing outside a cell in a test tube can allow for tighter control over the logic gates, the outputs or signals cannot be amplified by a cell and are less potent.

TRUMPET, which is smaller than a cell, taps into both cellular and non-cellular biocomputing benefits. “At its core, it is a nonliving logic gate system,” Adamala states, “It's a DNA-based logic gate system. But because we use enzymes, and the readout is enzymatic [where an enzyme replicates the fluorescent RNA], we end up with signal amplification." This readout means that the output from the TRUMPET system, a fluorescent RNA strand, can be replicated by nearby enzymes in the platform, making the light signal stronger. "So it combines the best of both worlds,” Adamala adds.

These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body.

The TRUMPET biocomputing process is relatively straightforward. “If the DNA [input] shows up as single-stranded, it will not be digested [by the logic gate], and you get this nice fluorescent output as the RNA is made from the single-stranded DNA, and that's a 1,” Adamala explains. "And if the DNA input is double-stranded, it gets digested by the enzymes in the logic gate, and there is no RNA created from the DNA, so there is no fluorescence, and the output is 0." On the story's leading image above, if the tube is "lit" with a purple color, that is a binary 1 signal for computing. If it's "off" it is a 0.

While still in research, TRUMPET and other biocomputing systems promise significant benefits to personalized healthcare and medicine. These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body. The study’s lead author and graduate student Judee Sharon is already beginning to research TRUMPET's ability for earlier cancer diagnoses. Because the inputs for TRUMPET are single or double-stranded DNA, any mutated or cancerous DNA could theoretically be detected from the platform through the biocomputing process. Theoretically, devices like TRUMPET could be used to detect cancer and other diseases earlier.

Adamala sees TRUMPET not only as a detection system but also as a potential cancer drug delivery system. “Ideally, you would like the drug only to turn on when it senses the presence of a cancer cell. And that's how we use the logic gates, which work in response to inputs like cancerous DNA. Then the output can be the production of a small molecule or the release of a small molecule that can then go and kill what needs killing, in this case, a cancer cell. So we would like to develop applications that use this technology to control the logic gate response of a drug’s delivery to a cell.”

Although platforms like TRUMPET are making progress, a lot more work must be done before they can be used commercially. “The process of translating mechanisms and architecture from biology to computing and vice versa is still an art rather than a science,” says Forrest. “It requires deep computer science and biology knowledge,” she adds. “Some people have compared interdisciplinary science to fusion restaurants—not all combinations are successful, but when they are, the results are remarkable.”

Crickets are low on fat, high on protein, and can be farmed sustainably. They are also crunchy.

In today’s podcast episode, Leaps.org Deputy Editor Lina Zeldovich speaks about the health and ecological benefits of farming crickets for human consumption with Bicky Nguyen, who joins Lina from Vietnam. Bicky and her business partner Nam Dang operate an insect farm named CricketOne. Motivated by the idea of sustainable and healthy protein production, they started their unconventional endeavor a few years ago, despite numerous naysayers who didn’t believe that humans would ever consider munching on bugs.

Yet, making creepy crawlers part of our diet offers many health and planetary advantages. Food production needs to match the rise in global population, estimated to reach 10 billion by 2050. One challenge is that some of our current practices are inefficient, polluting and wasteful. According to nonprofit EarthSave.org, it takes 2,500 gallons of water, 12 pounds of grain, 35 pounds of topsoil and the energy equivalent of one gallon of gasoline to produce one pound of feedlot beef, although exact statistics vary between sources.

Meanwhile, insects are easy to grow, high on protein and low on fat. When roasted with salt, they make crunchy snacks. When chopped up, they transform into delicious pâtes, says Bicky, who invents her own cricket recipes and serves them at industry and public events. Maybe that’s why some research predicts that edible insects market may grow to almost $10 billion by 2030. Tune in for a delectable chat on this alternative and sustainable protein.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Further reading:

More info on Bicky Nguyen

https://yseali.fulbright.edu.vn/en/faculty/bicky-n...

The environmental footprint of beef production

https://www.earthsave.org/environment.htm

https://www.watercalculator.org/news/articles/beef-king-big-water-footprints/

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00005/full

https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-footprint-food-methane

Insect farming as a source of sustainable protein

https://www.insectgourmet.com/insect-farming-growing-bugs-for-protein/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/insect-farming

Cricket flour is taking the world by storm

https://www.cricketflours.com/

https://talk-commerce.com/blog/what-brands-use-cricket-flour-and-why/

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.