Roald Dahl lost a child to measles. Here's what he has to say about the new outbreaks.

Olivia Dahl, shortly before her death from measles in 1962.

In 1962, the world was a remarkably different place: Neil Armstrong had yet to take his first steps on the lunar surface, John F. Kennedy was serving as president of the United States, and the Beatles were still a few years away from superstardom, having just recorded their first single.

The word “measles” was also a household name. Measles, which still exists in parts of the world today, is a highly contagious viral infection that typically causes fever, cough, muscle pain, fatigue, and a distinctive red rash. Measles was so pervasive around the world in 1962 that most children had gotten sick with it before the age of fifteen—but even though it was common, it was far from harmless. Measles killed around 400 to 500 people per year in the United States, and approximately 2.6 million people each year worldwide. Countless others suffered severe complications from measles, such as permanent blindness.

Tragedy hits home

Author Roald Dahl at his Buckinghamshire home with Olivia, daughter Chantal, and wife Patricia Neal in 1960.

Ben Martin / Getty Images

That year, British author Roald Dahl was beginning to make a name for himself, having just published his best-selling book James and the Giant Peach. Dahl, who would go on to write some of the most well-loved children’s books of the century, lived in southern England with his wife and three children. One day, Dahl and his wife, actress Patricia Neal, received word that there was an outbreak of measles at his daughters’ school.

While some parents quarantined their children, many others also considered measles a harmless childhood disease. Neal later recalled in her autobiography that a family member had advised her to “let the girls get measles,” thinking it would strengthen their immune systems and be “good for them.” Reluctantly, Dahl and Neal let their two school-aged children, Olivia and Chantal, continue school. Olivia, then aged seven, fell sick with the measles not long after that.

Neither Dahl nor Neal were terribly concerned about Olivia’s infection. Dahl would write later that it seemed to be taking its “usual course,” and the two would read and spend time together while Olivia rested. After a few days of fever and fatigue, Dahl wrote, Olivia seemed like she was “well on the road to recovery.”

But one afternoon, as the two sat on Olivia’s bed making animals out of pipe cleaners, Dahl noticed that Olivia’s “fingers and her mind were not working together.” When Dahl asked how she was feeling, Olivia replied, “I feel all sleepy.”

Within an hour, Dahl wrote, Olivia was unconscious. Within 12 hours, she was dead.

Olivia died of measles encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain caused by an infection. Approximately 1 in 1,000 people infected with measles develop encephalitis, and of those who develop it, between 10 and 20 percent will die.

Dahl was overcome with grief and wracked with guilt for being unable to prevent his daughter’s death. Mourning, Dahl threw himself into his writing and, in his spare time, spent hours lovingly constructing a rock garden on Olivia’s grave in a local churchyard.

After Olivia’s death, Dahl wrote sixteen novels and several collections of short stories, including Matilda, Fantastic Mr. Fox, and Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, which garnered him worldwide acclaim. His most influential piece of writing, however, wasn’t written until 1986.

A father's plea

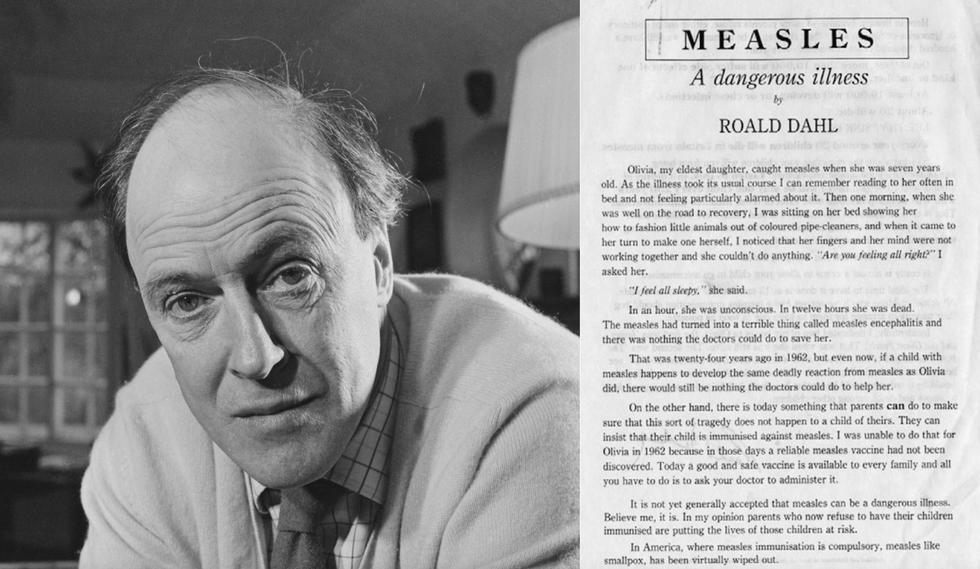

Roald Dahl and the open letter he wrote in 1986, encouraging parents to vaccinate their children against measles.

By 1986, measles was no longer the global health threat that it had been in the 1960s, thanks to a measles vaccine that became available just one year after Olivia had died. Still, in the United Kingdom alone, approximately 80,000 people every year were infected with measles. This bothered Dahl, especially since measles rates in the United States had dropped by 98 percent compared to pre-vaccine years. “Why do we have so much measles in Britain when the Americans have virtually gotten rid of it?,” Dahl was reported to have said.

So Dahl set out to prevent a tragedy like Olivia’s from happening again. With encouragement from several prominent public health activists, Dahl wrote an open letter addressed to parents in the UK. The letter recounted his daughter’s death from encephalitis and begged parents to protect their own children from measles:

“...there is today something that parents can do to make sure that this sort of tragedy does not happen to a child of theirs. They can insist that their child is immunised [sic] against measles. I was unable to do that for Olivia in 1962 because in those days a reliable measles vaccine had not been discovered. Today a good and safe vaccine is available to every family and all you have to do is to ask your doctor to administer it.”

Dahl went on to say that although many parents still viewed measles as a harmless illness, he knew from experience that it was not. Measles was capable of causing disability and death, Dahl wrote, whereas a child had a better chance of “choking on a chocolate bar” than developing any serious complication from the vaccine. Dahl ended his letter by saying how happy he knew Olivia would be “if only she could know that her death had helped to save a good deal of illness and death among other children.”

Dahl’s letter was published in early 1986 and distributed to local healthcare workers, schools, and to parents of children who were particularly at risk. As the letter circulated, vaccination rates continued to climb year after year.

Thirty-one years after Dahl’s letter was published, and 55 years after Olivia’s death, the World Health Organization declared in 2017 that measles had officially been eradicated for the first time in the UK thanks to high rates of vaccination.

A small step back

As vaccination rates decline, measles is now making a strong comeback in the United States and elsewhere.

Getty Images

Today, vaccination rates for the measles are in decline, and countries like the UK and the US, who had once eradicated measles completely, are now seeing a comeback. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported that between December 1, 2023 and January 23, 2024, 23 cases of measles had been confirmed across multiple states. The majority of these cases, they reported, were among children and adolescents who had traveled internationally and had not yet been vaccinated even though they were eligible to do so.

Roald Dahl passed away in 1990, but fortunately, his writing continues to live on. While readers can explore fantastical worlds through his novels and short stories, they can also look back to a reality when tragic deaths like Olivia’s happened far too often. The difference is that today, thanks to modern science, we now have the tools to stop them.

A company uses AI to fight muscle loss and unhealthy aging

In December 2022, a company called BioAge Labs published findings on a drug that worked to prevent muscular atrophy, or the loss of muscle strength and mass, in older people.

There’s a growing need to slow down the aging process. The world’s population is getting older and, according to one estimate, 80 million Americans will be 65 or older by 2040. As we age, the risk of many chronic diseases goes up, from cancer to heart disease to Alzheimer’s.

BioAge Labs, a company based in California, is using genetic data to help people stay healthy for longer. CEO Kristen Fortney was inspired by the genetics of people who live long lives and resist many age-related diseases. In 2015, she started BioAge to study them and develop drug therapies based on the company’s learnings.

The team works with special biobanks that have been collecting blood samples and health data from individuals for up to 45 years. Using artificial intelligence, BioAge is able to find the distinctive molecular features that distinguish those who have healthy longevity from those who don’t.

In December 2022, BioAge published findings on a drug that worked to prevent muscular atrophy, or the loss of muscle strength and mass, in older people. Much of the research on aging has been in worms and mice, but BioAge is focused on human data, Fortney says. “This boosts our chances of developing drugs that will be safe and effective in human patients.”

How it works

With assistance from AI, BioAge measures more than 100,000 molecules in each blood sample, looking at proteins, RNA and metabolites, or small molecules that are produced through chemical processes. The company uses many techniques to identify these molecules, some of which convert the molecules into charged atoms and then separating them according to their weight and charge. The resulting data is very complex, with many thousands of data points from patients being followed over the decades.

BioAge validates its targets by examining whether a pathway going awry is actually linked to the development of diseases, based on the company’s analysis of biobank health records and blood samples. The team uses AI and machine learning to identify these pathways, and the key proteins in the unhealthy pathways become their main drug targets. “The approach taken by BioAge is an excellent example of how we can harness the power of big data and advances in AI technology to identify new drugs and therapeutic targets,” says Lorna Harries, a professor of molecular genetics at the University of Exeter Medical School.

Martin Borch Jensen is the founder of Gordian Biotechnology, a company focused on using gene therapy to treat aging. He says BioAge’s use of AI allows them to speed up the process of finding promising drug candidates. However, it remains a challenge to separate pathologies from aspects of the natural aging process that aren’t necessarily bad. “Some of the changes are likely protective responses to things going wrong,” Jensen says. “Their data doesn’t…distinguish that so they’ll need to validate and be clever.”

Developing a drug for muscle loss

BioAge decided to focus on muscular atrophy because it affects many elderly people, making it difficult to perform everyday activities and increasing the risk of falls. Using the biobank samples, the team modeled different pathways that looked like they could improve muscle health. They found that people who had faster walking speeds, better grip strength and lived longer had higher levels of a protein called apelin.

Apelin is a peptide, or a small protein, that circulates in the blood. It is involved in the process by which exercise increases and preserves muscle mass. BioAge wondered if they could prevent muscular atrophy by increasing the amount of signaling in the apelin pathway. Instead of the long process of designing a drug, they decided to repurpose an existing drug made by another biotech company. This company, called Amgen, had explored the drug as a way to treat heart failure. It didn’t end up working for that purpose, but BioAge took note that the drug did seem to activate the apelin pathway.

BioAge tested its new, repurposed drug, BGE-105, and, in a phase 1 clinical trial, it protected subjects from getting muscular atrophy compared to a placebo group that didn’t receive the drug. Healthy volunteers over age 65 received infusions of the drug during 10 days spent in bed, as if they were on bed rest while recovering from an illness or injury; the elderly are especially vulnerable to muscle loss in this situation. The 11 people taking BGE-105 showed a 100 percent improvement in thigh circumference compared to 10 people taking the placebo. Ultrasound observations also revealed that the group taking the durg had enhanced muscle quality and a 73 percent increase in muscle thickness. One volunteer taking BGE-105 did have muscle loss compared to the the placebo group.

Heather Whitson, the director of the Duke University Centre for the study of aging and human development, says that, overall, the results are encouraging. “The clinical findings so far support the premise that AI can help us sort through enormous amounts of data and identify the most promising points for beneficial interventions.”

More studies are needed to find out which patients benefit the most and whether there are side effects. “I think further studies will answer more questions,” Whitson says, noting that BGE-105 was designed to enhance only one aspect of physiology associated with exercise, muscle strength. But exercise itself has many other benefits on mood, sleep, bones and glucose metabolism. “We don’t know whether BGE-105 will impact these other outcomes,” she says.

The future

BioAge is planning phase 2 trials for muscular atrophy in patients with obesity and those who have been hospitalized in an intensive care unit. Using the data from biobanks, they’ve also developed another drug, BGE-100, to treat chronic inflammation in the brain, a condition that can worsen with age and contributes to neurodegenerative diseases. The team is currently testing the drug in animals to assess its effects and find the right dose.

BioAge envisions that its drugs will have broader implications for health than treating any one specific disease. “Ultimately, we hope to pioneer a paradigm shift in healthcare, from treatment to prevention, by targeting the root causes of aging itself,” Fortney says. “We foresee a future where healthy longevity is within reach for all.”

How old fishing nets turn into chairs, car mats and Prada bags

A company called Aquafil is turning the fibers from fishing nets and old carpets into new threads for chairs, car mats, bikinis and Prada bags.

Discarded nylon fishing nets in the oceans are among the most harmful forms of plastic pollution. Every year, about 640,000 tons of fishing gear are left in our oceans and other water bodies to turn into death traps for marine life. London-based non-profit World Animal Protection estimates that entanglement in this “ghost gear” kills at least 136,000 seals, sea lions and large whales every year. Experts are challenged to estimate how many birds, turtles, fish and other species meet the same fate because the numbers are so high.

Since 2009, Giulio Bonazzi, the son of a small textile producer in northern Italy, has been working on a solution: an efficient recycling process for nylon. As CEO and chairman of a company called Aquafil, Bonazzi is turning the fibers from fishing nets – and old carpets – into new threads for car mats, Adidas bikinis, environmentally friendly carpets and Prada bags.

For Bonazzi, shifting to recycled nylon was a question of survival for the family business. His parents founded a textile company in 1959 in a garage in Verona, Italy. Fifteen years later, they started Aquafil to produce nylon for making raincoats, an enterprise that led to factories on three continents. But before the turn of the century, cheap products from Asia flooded the market and destroyed Europe’s textile production. When Bonazzi had finished his business studies and prepared to take over the family company, he wondered how he could produce nylon, which is usually produced from petrochemicals, in a way that was both successful and ecologically sustainable.

The question led him on an intellectual journey as he read influential books by activists such as world-renowned marine biologist Sylvia Earle and got to know Michael Braungart, who helped develop the Cradle-to-Cradle ethos of a circular economy. But the challenges of applying these ideologies to his family business were steep. Although fishing nets have become a mainstay of environmental fashion ads—and giants like Dupont and BASF have made breakthroughs in recycling nylon—no one had been able to scale up these efforts.

For ten years, Bonazzi tinkered with ideas for a proprietary recycling process. “It’s incredibly difficult because these products are not made to be recycled,” Bonazzi says. One complication is the variety of materials used in older carpets. “They are made to be beautiful, to last, to be useful. We vastly underestimated the difficulty when we started.”

Soon it became clear to Bonazzi that he needed to change the entire production process. He found a way to disintegrate old fibers with heat and pull new strings from the discarded fishing nets and carpets. In 2022, his company Aquafil produced more than 45,000 tons of Econyl, which is 100% recycled nylon, from discarded waste.

More than half of Aquafil’s recyclate is from used goods. According to the company, the recycling saves 90 percent of the CO2 emissions compared to the production of conventional nylon. That amounts to saving 57,100 tons of CO2 equivalents for every 10,000 tons of Econyl produced.

Bonazzi collects fishing nets from all over the world, including Norway and Chile—which have the world’s largest salmon productions—in addition to the Mediterranean, Turkey, India, Japan, Thailand, the Philippines, Pakistan, and New Zealand. He counts the government leadership of Seychelles as his most recent client; the island has prohibited ships from throwing away their fishing nets, creating the demand for a reliable recycler. With nearly 3,000 employees, Aquafil operates almost 40 collection and production sites in a dozen countries, including four collection sites for old carpets in the U.S., located in California and Arizona.

First, the dirty nets are gathered, washed and dried. Bonazzi explains that nets often have been treated with antifouling agents such as copper oxide. “We recycle the coating separately,” he says via Zoom from his home near Verona. “Copper oxide is a useful substance, why throw it away?”

Still, only a small percentage of Aquafil’s products are made from nets fished out of the ocean, so your new bikini may not have saved a strangled baby dolphin. “Generally, nylon recycling is a good idea,” says Christian Schiller, the CEO of Cirplus, the largest global marketplace for recyclates and plastic waste. “But contrary to what consumers think, people rarely go out to the ocean to collect ghost nets. Most are old, discarded nets collected on land. There’s nothing wrong with this, but I find it a tad misleading to label the final products as made from ‘ocean plastic,’ prompting consumers to think they’re helping to clean the oceans by buying these products.”

Aquafil gets most of its nets from aqua farms. Surprisingly, one of Aquafil’s biggest problems is finding enough waste. “I know, it’s hard to believe because waste is everywhere,” Bonazzi says. “But we need to find it in reliable quantity and quality.” He has invested millions in establishing reliable logistics to source the fishing nets. Then the nets get shredded into granules that can be turned into car mats for the new Hyundai Ioniq 5 or a Gucci swimsuit.

The process works similarly with carpets. In the U.S. alone, 3.5 billion pounds of carpet are discarded in landfills every year, and less than 3 percent are currently recycled. Aquafil has built a recycling plant in Phoenix to help divert 12,500 tons of carpets from the landfill every year. The carpets are shredded and deconstructed into three components: fillers such as calcium carbonate will be reused in the cement industry, synthetic fibers like polypropylene can be used for engineering plastics, and nylon. Only the pelletized nylon gets shipped back to Europe for the production of Econyl. “We ship only what’s necessary,” Bonazzi says. Nearly 50 percent of his nylon in Italy and Slovenia is produced from recyclate, and he hopes to increase the percentage to two-thirds in the next two years.

His clients include Interface, the leading world pioneer for sustainable flooring, and many other carpet producers plus more than 2500 fashion labels, including Gucci, Prada, Patagonia, Louis Vuitton, Adidas and Stella McCartney. “Stella McCartney just introduced a parka that’s made 100 percent from Econyl,” Bonazzi says. “We’re also in a lot of sportswear because Nylon is a good fabric for swimwear and for yoga clothes.” Next, he’s looking into sunglasses and chairs made with Econyl - for instance, the flexible ergonomic noho chair, designed by New Zealand company Formway.

“When I look at a landfill, I see a gold mine," Bonazzi says.

“Bonazzi decided many years ago to invest in the production of recycled nylon though industry giants halted similar plans after losing large investments,” says Anika Herrmann, vice president of the German Greentech-competitor Camm Solutions, which creates bio-based polymers from cane sugar and other ag waste. “We need role models like Bonazzi who create sustainable solutions with courage and a pioneering spirit. Like Aquafil, we count on strategic partnerships to enable fast upscaling along the entire production chain.”

Bonazzi’s recycled nylon is still five to 10 percent more expensive than conventionally produced material. However, brands are increasingly bending to the pressure of eco-conscious consumers who demand sustainable fashion. What helped Bonazzi was the recent rise of oil prices and the pressure on industries to reduce their carbon footprint. Now Bonazzi says, “When I look at a landfill, I see a gold mine.”

Ideally, the manufacturers take the products back when the client is done with it, and because the nylon can theoretically be reused nearly infinitely, the chair or bikini could be made into another chair or bikini. “But honestly,” Bonazzi half-jokes, “if someone returns a McCartney parka to me, I’ll just resell it because it’s so expensive.”

The next step: Bonazzi wants to reshape the entire nylon industry by pivoting from post-consumer nylon to plant-based nylon. In 2017, he began producing “nylon-6,” together with Genomatica in San Diego. The process uses sugar instead of petroleum. “The idea is to make the very same molecule from sugar, not from oil,” he says. The demonstration plant in Ljubljana, Slovenia, has already produced several hundred tons of nylon, and Genomatica is collaborating with Lululemon to produce plant-based yoga wear.

Bonazzi acknowledges that his company needs a few more years before the technology is ready to meet his ultimate goal, producing only recyclable products with no petrochemicals, low emissions and zero waste on an industrial scale. “Recycling is not enough,” he says. “You also need to produce the primary material in a sustainable way, with a low carbon footprint.”