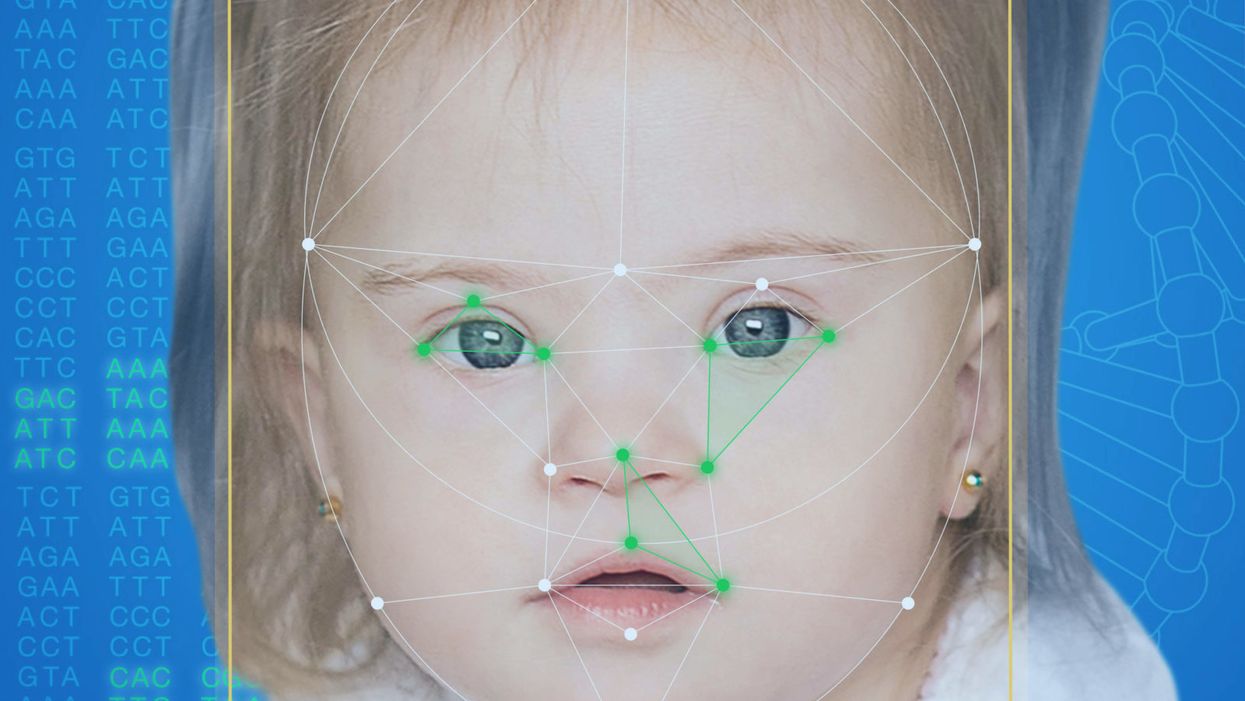

This App Helps Diagnose Rare Genetic Disorders from a Picture

FDNA's Face2Gene technology analyzes patient biometric data using artificial intelligence, identifying correlations with disease-causing genetic variations.

Medical geneticist Omar Abdul-Rahman had a hunch. He thought that the three-year-old boy with deep-set eyes, a rounded nose, and uplifted earlobes might have Mowat-Wilson syndrome, but he'd never seen a patient with the rare disorder before.

"If it weren't for the app I'm not sure I would have had the confidence to say 'yes you should spend $1000 on this test."

Rahman had already ordered genetic tests for three different conditions without any luck, and he didn't want to cost the family any more money—or hope—if he wasn't sure of the diagnosis. So he took a picture of the boy and uploaded the photo to Face2Gene, a diagnostic aid for rare genetic disorders. Sure enough, Mowat-Wilson came up as a potential match. The family agreed to one final genetic test, which was positive for the syndrome.

"If it weren't for the app I'm not sure I would have had the confidence to say 'yes you should spend $1000 on this test,'" says Rahman, who is now the director of Genetic Medicine at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, but saw the boy when he was in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in 2012.

"Families who are dealing with undiagnosed diseases never know what's going to come around the corner, what other organ system might be a problem next week," Rahman says. With a diagnosis, "You don't have to wait for the other shoe to drop because now you know the extent of the condition."

A diagnosis is the first and most important step for patients to attain medical care. Disease prognosis, treatment plans, and emotional coping all stem from this critical phase. But diagnosis can also be the trickiest part of the process, particularly for rare disorders. According to one European survey, 40 percent of rare diseases are initially misdiagnosed.

Healthcare professionals and medical technology companies hope that facial recognition software will help prevent families from facing difficult disruptions due to misdiagnoses.

"Patients with rare diseases or genetic disorders go through a long period of diagnostic odyssey, and just putting a name to a syndrome or finding a diagnosis can be very helpful and relieve a lot of tension for the family," says Dekel Gelbman, CEO of FDNA.

Consequently, a misdiagnosis can be devastating for families. Money and time may have been wasted on fruitless treatments, while opportunities for potentially helpful therapies or clinical trials were missed. Parents led down the wrong path must change their expectations of their child's long-term prognosis and care. In addition, they may be misinformed regarding future decisions about family planning.

Healthcare professionals and medical technology companies hope that facial recognition software will help prevent families from facing these difficult disruptions by improving the accuracy and ease of diagnosing genetic disorders. Traditionally, doctors diagnose these types of conditions by identifying unique patterns of facial features, a practice called dysmorphology. Trained physicians can read a child's face like a map and detect any abnormal ridges or plateaus—wide-set eyes, broad forehead, flat nose, rotated ears—that, combined with other symptoms such as intellectual disability or abnormal height and weight, signify a specific genetic disorder.

These morphological changes can be subtle, though, and often only specialized medical geneticists are able to detect and interpret these facial clues. What's more, some genetic disorders are so rare that even a specialist may not have encountered it before, much less a general practitioner. Diagnosing rare conditions has improved thanks to genomic testing that can confirm (or refute) a doctor's suspicion. Yet with thousands of variants in each person's genome, identifying the culprit mutation or deletion can be extremely difficult if you don't know what you're looking for.

Facial recognition technology is trying to take some of the guesswork out of this process. Software such as the Face2Gene app use machine learning to compare a picture of a patient against images of thousands of disorders and come back with suggestions of possible diagnoses.

"This is a classic field for artificial intelligence because no human being can really have enough knowledge and enough experience to be able to do this for thousands of different disorders."

"When we met a geneticist for the first time we were pretty blown away with the fact that they actually use their own human pattern recognition" to diagnose patients, says Gelbman. "This is a classic field for AI [artificial intelligence], for machine learning because no human being can really have enough knowledge and enough experience to be able to do this for thousands of different disorders."

When a physician uploads a photo to the app, they are given a list of different diagnostic suggestions, each with a heat map to indicate how similar the facial features are to a classic representation of the syndrome. The physician can hone the suggestions by adding in other symptoms or family history. Gelbman emphasized that the app is a "search and reference tool" and should not "be used to diagnose or treat medical conditions." It is not approved by the FDA as a diagnostic.

"As a tool, we've all been waiting for this, something that can help everyone," says Julian Martinez-Agosto, an associate professor in human genetics and pediatrics at UCLA. He sees the greatest benefit of facial recognition technology in its ability to empower non-specialists to make a diagnosis. Many areas, including rural communities or resource-poor countries, do not have access to either medical geneticists trained in these types of diagnostics or genomic screens. Apps like Face2Gene can help guide a general practitioner or flag diseases they might not be familiar with.

One concern is that most textbook images of genetic disorders come from the West, so the "classic" face of a condition is often a child of European descent.

Maximilian Muenke, a senior investigator at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), agrees that in many countries, facial recognition programs could be the only way for a doctor to make a diagnosis.

"There are only geneticists in countries like the U.S., Canada, Europe, Japan. In most countries, geneticists don't exist at all," Muenke says. "In Nigeria, the most populous country in all of Africa with 160 million people, there's not a single clinical geneticist. So in a country like that, facial recognition programs will be sought after and will be extremely useful to help make a diagnosis to the non-geneticists."

One concern about providing this type of technology to a global population is that most textbook images of genetic disorders come from the West, so the "classic" face of a condition is often a child of European descent. However, the defining facial features of some of these disorders manifest differently across ethnicities, leaving clinicians from other geographic regions at a disadvantage.

"Every syndrome is either more easy or more difficult to detect in people from different geographic backgrounds," explains Muenke. For example, "in some countries of Southeast Asia, the eyes are slanted upward, and that happens to be one of the findings that occurs mostly with children with Down Syndrome. So then it might be more difficult for some individuals to recognize Down Syndrome in children from Southeast Asia."

There is a risk that providing this type of diagnostic information online will lead to parents trying to classify their own children.

To combat this issue, Muenke helped develop the Atlas of Human Malformation Syndromes, a database that incorporates descriptions and pictures of patients from every continent. By providing examples of rare genetic disorders in children from outside of the United States and Europe, Muenke hopes to provide clinicians with a better understanding of what to look for in each condition, regardless of where they practice.

There is a risk that providing this type of diagnostic information online will lead to parents trying to classify their own children. Face2Gene is free to download in the app store, although users must be authenticated by the company as a healthcare professional before they can access the database. The NHGRI Atlas can be accessed by anyone through their website. However, Martinez and Muenke say parents already use Google and WebMD to look up their child's symptoms; facial recognition programs and databases are just an extension of that trend. In fact, Martinez says, "Empowering families is another way to facilitate access to care. Some families live in rural areas and have no access to geneticists. If they can use software to get a diagnosis and then contact someone at a large hospital, it can help facilitate the process."

Martinez also says the app could go further by providing greater transparency about how the program makes its assessments. Giving clinicians feedback about why a diagnosis fits certain facial features would offer a valuable teaching opportunity in addition to a diagnostic aid.

Both Martinez and Muenke think the technology is an innovation that could vastly benefit patients. "In the beginning, I was quite skeptical and I could not believe that a machine could replace a human," says Muenke. "However, I am a convert that it actually can help tremendously in making a diagnosis. I think there is a place for facial recognition programs, and I am a firm believer that this will spread over the next five years."

Questions remain about new drug for hot flashes

In May, a new drug, Fezolinetant, was approved by the FDA to treat hot flashes associated with menopause.

Vascomotor symptoms (VMS) is the medical term for hot flashes associated with menopause. You are going to hear a lot more about it because a company has a new drug to sell. Here is what you need to know.

Menopause marks the end of a woman’s reproductive capacity. Normal hormonal production associated with that monthly cycle becomes erratic and finally ceases. For some women the transition can be relatively brief with only modest symptoms, while for others the body's “thermostat” in the brain is disrupted and they experience hot flashes and other symptoms that can disrupt daily activity. Lifestyle modification and drugs such as hormone therapy can provide some relief, but women at risk for cancer are advised not to use them and other women choose not to do so.

Fezolinetant, sold by Astellas Pharma Inc. under the product name Veozah™, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on May 12 to treat hot flashes associated with menopause. It is the first in a new class of drugs called neurokinin 3 receptor antagonists, which block specific neurons in the brain “thermostat” that trigger VMS. It does not appear to affect other symptoms of menopause. As with many drugs targeting a brain cell receptor, it must be taken continuously for a few days to build up a good therapeutic response, rather than working as a rescue product such as an asthma inhaler to immediately treat that condition.

Hot flashes vary greatly and naturally get better or resolve completely with time. That contributes to a placebo effect and makes it more difficult to judge the outcome of any intervention. Early this year, a meta analysis of 17 studies of drug trials for hot flashes found an unusually large placebo response in those types of studies; the placebo groups had an average of 5.44 fewer hot flashes and a 36 percent reduction in their severity.

In studies of fezolinetant, the drug recently approved by the FDA, the placebo benefit was strong and persistent. The drug group bested the placebo response to a statistically significant degree but, “If people have gone from 11 hot flashes a day to eight or seven in the placebo group and down to a couple fewer ones in the drug groups, how meaningful is that? Having six hot flashes a day is still pretty unpleasant,” says Diana Zuckerman, president of the National Center for Health Research (NCHR), a health oriented think tank.

“Is a reduction compared to placebo of 2-3 hot flashes per day, in a population of women experiencing 10-11 moderate to severe hot flashes daily, enough relief to be clinically meaningful?” Andrea LaCroix asked a commentary published in Nature Medicine. She is an epidemiologist at the University of California San Diego and a leader of the MsFlash network that has conducted a handful of NIH-funded studies on menopause.

Questions Remain

LaCroix and others have raised questions about how Astellas, the company that makes the new drug, handled missing data from patients who dropped out of the clinical trials. “The lack of detailed information about important parameters such as adherence and missing data raises concerns that the reported benefits of fezolinetant very likely overestimate those that will be observed in clinical practice," LaCroix wrote.

In response to this concern, Anna Criddle, director of global portfolio communications at Astellas, wrote in an email to Leaps.org: “…a full analysis of data, including adherence data and any impact of missing data, was submitted for assessment by [the FDA].”

The company ran the studies at more than 300 sites around the world. Curiously, none appear to have been at academic medical centers, which are known for higher quality research. Zuckerman says, "When somebody is paid to do a study, if they want to get paid to do another study by the same company, they will try to make sure that the results are the results that the company wants.”

Criddle said that Astellas picked the sites “that would allow us to reach a diverse population of women, including race and ethnicity.”

A trial of a lower dose of the drug was conducted in Asia. In March 2022, Astellas issued a press release saying it had failed to prove effectiveness. No further data has been released. Astellas still plans to submit the data, according to Criddle. Results from clinical trials funded by the U.S. goverment must be reported on clinicaltrials.gov within one year of the study's completion - a deadline that, in this case, has expired.

The measurement scale for hot flashes used in the studies, mild-moderate-severe, also came in for criticism. “It is really not good scale, there probably isn’t a broad enough range of things going on or descriptors,” says David Rind. He is chief medical officer of the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER), a nonprofit authority on new drugs. It conducted a thorough review and analysis of fezolinestant using then existing data gathered from conference abstracts, posters and presentations and included a public stakeholder meeting in December. A 252-page report was published in January, finding “considerable uncertainty about the comparative net health benefits of fezolinetant” versus hormone therapy.

Questions surrounding some of these issues might have been answered if the FDA had chosen to hold a public advisory committee meeting on fezolinetant, which it regularly does for first in class medicines. But the agency decided such a meeting was unnecessary.

Cost

There was little surprise when Astellas announced a list price for fezolinetant of $550 a month ($6000 annually) and a program of patient assistance to ease out of pocket expenses. The company had already incurred large expenses.

In 2017 Astellas purchased the company that originally developed fezolinetant for $534 million plus several hundred million in potential royalties. The drug company ran a "disease awareness” ad, Heat on the Street, hat aired during the Super Bowl in February, where 30 second ads cost about $7 million. Industry analysts have projected sales to be $1.9 billion by 2028.

ICER’s pre-approval evaluation said fezolinetant might "be considered cost-effective if priced around $2,000 annually. ... [It]will depend upon its price and whether it is considered an alternative to MHT [menopause hormone treatment] for all women or whether it will primarily be used by women who cannot or will not take MHT."

Criddle wrote that Astellas set the price based on the novelty of the science, the quality of evidence for the drug and its uniqueness compared to the rest of the market. She noted that an individual’s payment will depend on how much their insurance company decides to cover. “[W]e expect insurance coverage to increase over the course of the year and to achieve widespread coverage in the U.S. over time.”

Leaps.org wrote to and followed up with nine of the largest health insurers/providers asking basic questions about their coverage of fezolinetant. Only two responded. Jennifer Martin, the deputy chief consultant for pharmacy benefits management at the Department of Veterans Affairs, said the agency “covers all drugs from the date that they are launched.” Decisions on whether it will be included in the drug formulary and what if any copays might be required are under review.

“[Fezolinetant] will go through our standard P&T Committee [patient and treatment] review process in the next few months, including a review of available efficacy data, safety data, clinical practice guidelines, and comparison with other agents used for vasomotor symptoms of menopause," said Phil Blando, executive director of corporate communications for CVS Health.

Other insurers likely are going through a similar process to decide issues such as limiting coverage to women who are advised not to use hormones, how much copay will be required, and whether women will be required to first try other options or obtain approvals before getting a prescription.

Rind wants to see a few years of use before he prescribes fezolinetant broadly, and believes most doctors share his view. Nor will they be eager to fill out the additional paperwork required for women to participate in the Astellas patient assistance program, he added.

Safety

Astellas is marketing its drug by pointing out risks of hormone therapy, such as a recent paper in The BMJ, which noted that women who took hormones for even a short period of time had a 24 percent increased risk of dementia. While the percentage was scary, the combined number of women both on and off hormones who developed dementia was small. And it is unclear whether hormones are causing dementia or if more severe hot flashes are a marker for higher risk of developing dementia. This information is emerging only after 80 years of hundreds of millions of women using hormones.

In contrast, the label for fezolinetant prohibits “concomitant use with CYP1A2 inhibitors” and requires testing for liver and kidney function prior to initiating the drug and every three months thereafter. There is no human or animal data on use in a geriatric population, defined as 65 or older, a group that is likely to use the drug. Only a few thousand women have ever taken fezolinetant and most have used it for just a few months.

Options

A woman seeking relief from symptoms of menopause would like to see how fezolintant compares with other available treatment options. But Astellas did not conduct such a study and Andrea LaCroix says it is unlikely that anyone ever will.

ICER has come the closest, with a side-by-side analysis of evidence-based treatments and found that fezolinetant performed quite similarly and modestly as the others in providing relief from hot flashes. Some treatments also help with other symptoms of menopause, which fezolinetant does not.

There are many coping strategies that women can adopt to deal with hot flashes; one of the most common is dressing in layers (such as a sleeveless blouse with a sweater) that can be added or subtracted as conditions require. Avoiding caffeine, hot liquids, and spicy foods is another common strategy. “I stopped drinking hot caffeinated drinks…for several years, and you get out of the habit of drinking them,” says Zuckerman.

LaCroix curates those options at My Meno Plan, which includes a search function where you can enter your symptoms and identify which treatments might work best for you. It also links to published research papers. She says the goal is to empower women with information to make informed decisions about menopause.

A company in England has made a test that picks out the compounds from breath that reveal if people have liver disease.

Every year, around two million people worldwide die of liver disease. While some people inherit the disease, it’s most commonly caused by hepatitis, obesity and alcoholism. These underlying conditions kill liver cells, causing scar tissue to form until eventually the liver cannot function properly. Since 1979, deaths due to liver disease have increased by 400 percent.

The sooner the disease is detected, the more effective treatment can be. But once symptoms appear, the liver is already damaged. Around 50 percent of cases are diagnosed only after the disease has reached the final stages, when treatment is largely ineffective.

To address this problem, Owlstone Medical, a biotech company in England, has developed a breath test that can detect liver disease earlier than conventional approaches. Human breath contains volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that change in the first stages of liver disease. Owlstone’s breath test can reliably collect, store and detect VOCs, while picking out the specific compounds that reveal liver disease.

“There’s a need to screen more broadly for people with early-stage liver disease,” says Owlstone’s CEO Billy Boyle. “Equally important is having a test that's non-invasive, cost effective and can be deployed in a primary care setting.”

The standard tool for detection is a biopsy. It is invasive and expensive, making it impractical to use for people who aren't yet symptomatic. Meanwhile, blood tests are less invasive, but they can be inaccurate and can’t discriminate between different stages of the disease.

In the past, breath tests have not been widely used because of the difficulties of reliably collecting and storing breath. But Owlstone’s technology could help change that.

The team is testing patients in the early stages of advanced liver disease, or cirrhosis, to identify and detect these biomarkers. In an initial study, Owlstone’s breathalyzer was able to pick out patients who had early cirrhosis with 83 percent sensitivity.

Boyle’s work is personally motivated. His wife died of colorectal cancer after she was diagnosed with a progressed form of the disease. “That was a big impetus for me to see if this technology could work in early detection,” he says. “As a company, Owlstone is interested in early detection across a range of diseases because we think that's a way to save lives and a way to save costs.”

How it works

In the past, breath tests have not been widely used because of the difficulties of reliably collecting and storing breath. But Owlstone’s technology could help change that.

Study participants breathe into a mouthpiece attached to a breath sampler developed by Owlstone. It has cartridges are designed and optimized to collect gases. The sampler specifically targets VOCs, extracting them from atmospheric gases in breath, to ensure that even low levels of these compounds are captured.

The sampler can store compounds stably before they are assessed through a method called mass spectrometry, in which compounds are converted into charged atoms, before electromagnetic fields filter and identify even the tiniest amounts of charged atoms according to their weight and charge.

The top four compounds in our breath

In an initial study, Owlstone captured VOCs in breath to see which ones could help them tell the difference between people with and without liver disease. They tested the breath of 46 patients with liver disease - most of them in the earlier stages of cirrhosis - and 42 healthy people. Using this data, they were able to create a diagnostic model. Individually, compounds like 2-Pentanone and limonene performed well as markers for liver disease. Owlstone achieved even better performance by examining the levels of the top four compounds together, distinguishing between liver disease cases and controls with 95 percent accuracy.

“It was a good proof of principle since it looks like there are breath biomarkers that can discriminate between diseases,” Boyle says. “That was a bit of a stepping stone for us to say, taking those identified, let’s try and dose with specific concentrations of probes. It's part of building the evidence and steering the clinical trials to get to liver disease sensitivity.”

Sabine Szunerits, a professor of chemistry in Institute of Electronics at the University of Lille, sees the potential of Owlstone’s technology.

“Breath analysis is showing real promise as a clinical diagnostic tool,” says Szunerits, who has no ties with the company. “Owlstone Medical’s technology is extremely effective in collecting small volatile organic biomarkers in the breath. In combination with pattern recognition it can give an answer on liver disease severity. I see it as a very promising way to give patients novel chances to be cured.”

Improving the breath sampling process

Challenges remain. With more than one thousand VOCs found in the breath, it can be difficult to identify markers for liver disease that are consistent across many patients.

Julian Gardner is a professor of electrical engineering at Warwick University who researches electronic sensing devices. “Everyone’s breath has different levels of VOCs and different ones according to gender, diet, age etc,” Gardner says. “It is indeed very challenging to selectively detect the biomarkers in the breath for liver disease.”

So Owlstone is putting chemicals in the body that they know interact differently with patients with liver disease, and then using the breath sampler to measure these specific VOCs. The chemicals they administer are called Exogenous Volatile Organic Compound) probes, or EVOCs.

Most recently, they used limonene as an EVOC probe, testing 29 patients with early cirrhosis and 29 controls. They gave the limonene to subjects at specific doses to measure how its concentrations change in breath. The aim was to try and see what was happening in their livers.

“They are proposing to use drugs to enhance the signal as they are concerned about the sensitivity and selectivity of their method,” Gardner says. “The approach of EVOC probes is probably necessary as you can then eliminate the person-to-person variation that will be considerable in the soup of VOCs in our breath.”

Through these probes, Owlstone could identify patients with liver disease with 83 percent sensitivity. By targeting what they knew was a disease mechanism, they were able to amplify the signal. The company is starting a larger clinical trial, and the plan is to eventually use a panel of EVOC probes to make sure they can see diverging VOCs more clearly.

“I think the approach of using probes to amplify the VOC signal will ultimately increase the specificity of any VOC breath tests, and improve their practical usability,” says Roger Yazbek, who leads the South Australian Breath Analysis Research (SABAR) laboratory in Flinders University. “Whilst the findings are interesting, it still is only a small cohort of patients in one location.”

The future of breath diagnosis

Owlstone wants to partner with pharmaceutical companies looking to learn if their drugs have an effect on liver disease. They’ve also developed a microchip, a miniaturized version of mass spectrometry instruments, that can be used with the breathalyzer. It is less sensitive but will enable faster detection.

Boyle says the company's mission is for their tests to save 100,000 lives. "There are lots of risks and lots of challenges. I think there's an opportunity to really establish breath as a new diagnostic class.”