This App Helps Diagnose Rare Genetic Disorders from a Picture

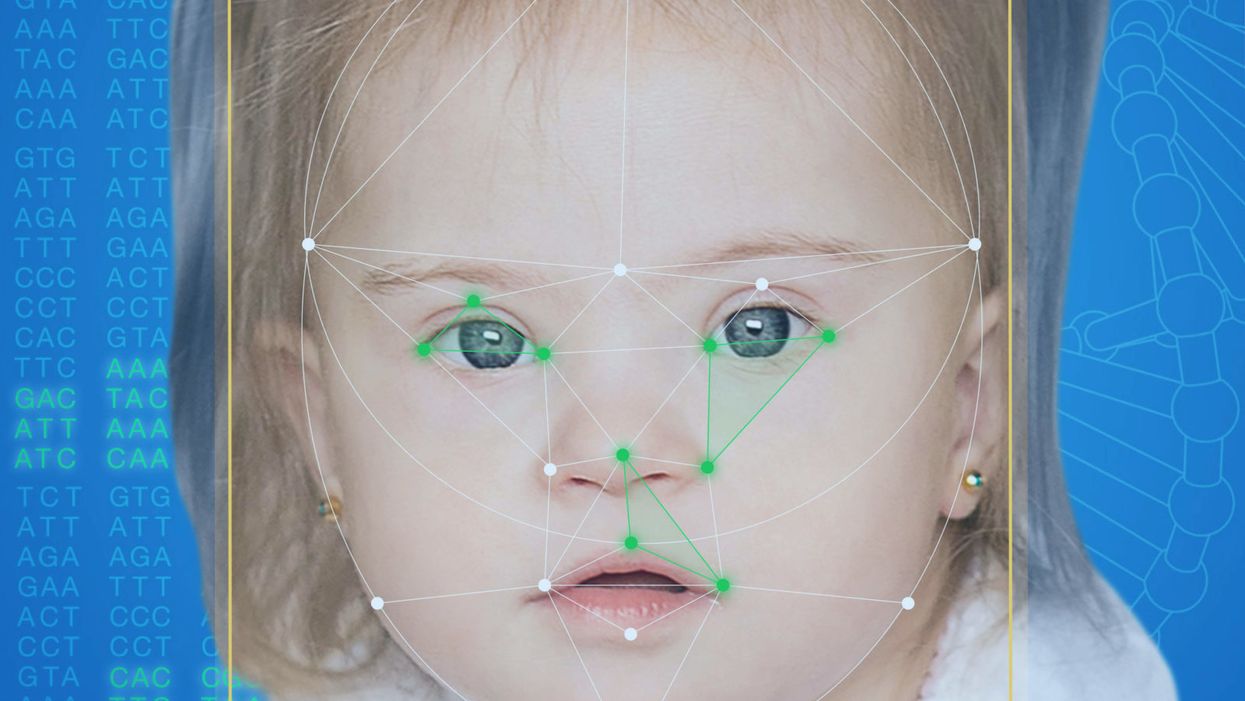

FDNA's Face2Gene technology analyzes patient biometric data using artificial intelligence, identifying correlations with disease-causing genetic variations.

Medical geneticist Omar Abdul-Rahman had a hunch. He thought that the three-year-old boy with deep-set eyes, a rounded nose, and uplifted earlobes might have Mowat-Wilson syndrome, but he'd never seen a patient with the rare disorder before.

"If it weren't for the app I'm not sure I would have had the confidence to say 'yes you should spend $1000 on this test."

Rahman had already ordered genetic tests for three different conditions without any luck, and he didn't want to cost the family any more money—or hope—if he wasn't sure of the diagnosis. So he took a picture of the boy and uploaded the photo to Face2Gene, a diagnostic aid for rare genetic disorders. Sure enough, Mowat-Wilson came up as a potential match. The family agreed to one final genetic test, which was positive for the syndrome.

"If it weren't for the app I'm not sure I would have had the confidence to say 'yes you should spend $1000 on this test,'" says Rahman, who is now the director of Genetic Medicine at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, but saw the boy when he was in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in 2012.

"Families who are dealing with undiagnosed diseases never know what's going to come around the corner, what other organ system might be a problem next week," Rahman says. With a diagnosis, "You don't have to wait for the other shoe to drop because now you know the extent of the condition."

A diagnosis is the first and most important step for patients to attain medical care. Disease prognosis, treatment plans, and emotional coping all stem from this critical phase. But diagnosis can also be the trickiest part of the process, particularly for rare disorders. According to one European survey, 40 percent of rare diseases are initially misdiagnosed.

Healthcare professionals and medical technology companies hope that facial recognition software will help prevent families from facing difficult disruptions due to misdiagnoses.

"Patients with rare diseases or genetic disorders go through a long period of diagnostic odyssey, and just putting a name to a syndrome or finding a diagnosis can be very helpful and relieve a lot of tension for the family," says Dekel Gelbman, CEO of FDNA.

Consequently, a misdiagnosis can be devastating for families. Money and time may have been wasted on fruitless treatments, while opportunities for potentially helpful therapies or clinical trials were missed. Parents led down the wrong path must change their expectations of their child's long-term prognosis and care. In addition, they may be misinformed regarding future decisions about family planning.

Healthcare professionals and medical technology companies hope that facial recognition software will help prevent families from facing these difficult disruptions by improving the accuracy and ease of diagnosing genetic disorders. Traditionally, doctors diagnose these types of conditions by identifying unique patterns of facial features, a practice called dysmorphology. Trained physicians can read a child's face like a map and detect any abnormal ridges or plateaus—wide-set eyes, broad forehead, flat nose, rotated ears—that, combined with other symptoms such as intellectual disability or abnormal height and weight, signify a specific genetic disorder.

These morphological changes can be subtle, though, and often only specialized medical geneticists are able to detect and interpret these facial clues. What's more, some genetic disorders are so rare that even a specialist may not have encountered it before, much less a general practitioner. Diagnosing rare conditions has improved thanks to genomic testing that can confirm (or refute) a doctor's suspicion. Yet with thousands of variants in each person's genome, identifying the culprit mutation or deletion can be extremely difficult if you don't know what you're looking for.

Facial recognition technology is trying to take some of the guesswork out of this process. Software such as the Face2Gene app use machine learning to compare a picture of a patient against images of thousands of disorders and come back with suggestions of possible diagnoses.

"This is a classic field for artificial intelligence because no human being can really have enough knowledge and enough experience to be able to do this for thousands of different disorders."

"When we met a geneticist for the first time we were pretty blown away with the fact that they actually use their own human pattern recognition" to diagnose patients, says Gelbman. "This is a classic field for AI [artificial intelligence], for machine learning because no human being can really have enough knowledge and enough experience to be able to do this for thousands of different disorders."

When a physician uploads a photo to the app, they are given a list of different diagnostic suggestions, each with a heat map to indicate how similar the facial features are to a classic representation of the syndrome. The physician can hone the suggestions by adding in other symptoms or family history. Gelbman emphasized that the app is a "search and reference tool" and should not "be used to diagnose or treat medical conditions." It is not approved by the FDA as a diagnostic.

"As a tool, we've all been waiting for this, something that can help everyone," says Julian Martinez-Agosto, an associate professor in human genetics and pediatrics at UCLA. He sees the greatest benefit of facial recognition technology in its ability to empower non-specialists to make a diagnosis. Many areas, including rural communities or resource-poor countries, do not have access to either medical geneticists trained in these types of diagnostics or genomic screens. Apps like Face2Gene can help guide a general practitioner or flag diseases they might not be familiar with.

One concern is that most textbook images of genetic disorders come from the West, so the "classic" face of a condition is often a child of European descent.

Maximilian Muenke, a senior investigator at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), agrees that in many countries, facial recognition programs could be the only way for a doctor to make a diagnosis.

"There are only geneticists in countries like the U.S., Canada, Europe, Japan. In most countries, geneticists don't exist at all," Muenke says. "In Nigeria, the most populous country in all of Africa with 160 million people, there's not a single clinical geneticist. So in a country like that, facial recognition programs will be sought after and will be extremely useful to help make a diagnosis to the non-geneticists."

One concern about providing this type of technology to a global population is that most textbook images of genetic disorders come from the West, so the "classic" face of a condition is often a child of European descent. However, the defining facial features of some of these disorders manifest differently across ethnicities, leaving clinicians from other geographic regions at a disadvantage.

"Every syndrome is either more easy or more difficult to detect in people from different geographic backgrounds," explains Muenke. For example, "in some countries of Southeast Asia, the eyes are slanted upward, and that happens to be one of the findings that occurs mostly with children with Down Syndrome. So then it might be more difficult for some individuals to recognize Down Syndrome in children from Southeast Asia."

There is a risk that providing this type of diagnostic information online will lead to parents trying to classify their own children.

To combat this issue, Muenke helped develop the Atlas of Human Malformation Syndromes, a database that incorporates descriptions and pictures of patients from every continent. By providing examples of rare genetic disorders in children from outside of the United States and Europe, Muenke hopes to provide clinicians with a better understanding of what to look for in each condition, regardless of where they practice.

There is a risk that providing this type of diagnostic information online will lead to parents trying to classify their own children. Face2Gene is free to download in the app store, although users must be authenticated by the company as a healthcare professional before they can access the database. The NHGRI Atlas can be accessed by anyone through their website. However, Martinez and Muenke say parents already use Google and WebMD to look up their child's symptoms; facial recognition programs and databases are just an extension of that trend. In fact, Martinez says, "Empowering families is another way to facilitate access to care. Some families live in rural areas and have no access to geneticists. If they can use software to get a diagnosis and then contact someone at a large hospital, it can help facilitate the process."

Martinez also says the app could go further by providing greater transparency about how the program makes its assessments. Giving clinicians feedback about why a diagnosis fits certain facial features would offer a valuable teaching opportunity in addition to a diagnostic aid.

Both Martinez and Muenke think the technology is an innovation that could vastly benefit patients. "In the beginning, I was quite skeptical and I could not believe that a machine could replace a human," says Muenke. "However, I am a convert that it actually can help tremendously in making a diagnosis. I think there is a place for facial recognition programs, and I am a firm believer that this will spread over the next five years."

Time to visit your TikTok doc? The good and bad of doctors on social media

Rakhi Patel is among an increasing number of health care professionals, including doctors and nurses, who maintain an active persona on Instagram, TikTok and other social media sites.

Rakhi Patel has carved a hobby out of reviewing pizza — her favorite food — on Instagram. In a nod to her preferred topping, she calls herself thepepperoniqueen. Photos and videos show her savoring slices from scores of pizzerias. In some of them, she’s wearing scrubs — her attire as an inpatient neurology physician associate at Tufts Medical Center in Boston.

“Depending on how you dress your pizza, it can be more nutritious,” said Patel, who suggests a thin crust, sugarless tomato sauce and vegetables galore as healthier alternatives. “There are no boundaries for a health care professional to enjoy pizza.”

Beyond that, “pizza fuels my mental health and makes me happy, especially when loaded with pepperoni,” she said. “If I’m going to be a pizza connoisseur, then I also need to take care of my physical health by ensuring that I get at least three days of exercise per week and eat nutritiously when I’m not eating pizza.”

She’s among an increasing number of health care professionals, including doctors and nurses, who maintain an active persona on social media, according to bioethics researchers. They share their hobbies and interests with people inside and outside the world of medicine, helping patients and the public become acquainted with the humans behind the scrubs or white coats. Other health care experts limit their posts to medical topics, while some opt for a combination of personal and professional commentaries. Depending on the posts, ethical issues may come into play.

“Health care professionals are quite prevalent on social media,” said Mercer Gary, a postdoctoral researcher at The Hastings Center, an independent bioethics research institute in Garrison, New York. “They’ve been posting on #medTwitter for many years, mainly to communicate with one another, but, of course, anyone can see the threads. Most recently, doctors and nurses have become a presence on TikTok.”

On social media, many health care providers perceive themselves to be “humanizing” their profession by coming across as more approachable — “reminding patients that providers are people and workers, as well as repositories of medical expertise,” Gary said. As a result, she noted that patients who are often intimidated by clinicians may feel comfortable enough to overcome barriers to scheduling health care appointments. The use of TikTok in particular may help doctors and nurses connect with younger followers.

When health care providers post on social media, they must bear in mind that they have legal and ethical duties to their patients, profession and society, said Elizabeth Levy, founder and director of Physicians for Justice.

While enduring three years of pandemic conditions, many health care professionals have struggled with burnout, exhaustion and moral distress. “Much health care provider content on social media seeks to expose the difficulties of the work,” Gary added. “TikTok and Instagram reels have shown health care providers crying after losing a patient or exhausted after a night shift in the emergency department.”

A study conducted in Beijing, China and published last year found that TikTok is the world’s most rapidly growing video application, amassing 1.6 billion users in 2021. “More and more patients are searching for information on genitourinary cancers via TikTok,” the study’s authors wrote in Frontiers in Oncology, referring to cancers of the urinary tracts and male reproductive organs. Among the 61 sample videos examined by the researchers, health care practitioners contributed the content in 29, or 47 percent, of them. Yet, 22 posts, 36 percent, were misinformative, mostly due to outdated information.

More than half of the videos offered good content on disease symptoms and examinations. The authors concluded that “most videos on genitourinary cancers on TikTok are of poor to medium quality and reliability. However, videos posted by media agencies enjoyed great public attention and interaction. Medical practitioners could improve the video quality by cooperating with media agencies and avoiding unexplained terminologies.”

When health care providers post on social media, they must bear in mind that they have legal and ethical duties to their patients, profession and society, said Elizabeth Levy, founder and director of Physicians for Justice in Irvine, Calif., a nonprofit network of volunteer physicians partnering with public interest lawyers to address the social determinants of health.

“Providers are also responsible for understanding the mechanics of their posts,” such as who can see these messages and how long they stay up, Levy said. As a starting point for figuring what’s acceptable, providers could look at social media guidelines put out by their professional associations. Even beyond that, though, they must exercise prudent judgment. “As social media continues to evolve, providers will also need to stay updated with the changing risks and benefits of participation.”

Patients often research their providers online, so finding them on social media can help inform about values and approaches to care, said M. Sara Rosenthal, a professor and founding director of the program for bioethics and chair of the hospital ethics committee at the University of Kentucky College of Medicine.

Health care providers’ posts on social media also could promote patient education. They can advance informed consent and help patients navigate the risks and benefits of various treatments or preventive options. However, providers could violate ethical principles if they espouse “harmful, risky or questionable therapies or medical advice that is contrary to clinical practice guidelines or accepted standards of care,” Rosenthal said.

Inappropriate self-disclosure also can affect a provider’s reputation, said Kelly Michelson, a professor of pediatrics and director of the Center for Bioethics and Medical Humanities at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. A clinician’s obligations to professionalism extend beyond those moments when they are directly taking care of their patients, she said. “Many experts recommend against clinicians ‘friending’ patients or the families on social media because it blurs the patient-clinician boundary.”

Meanwhile, clinicians need to adhere closely to confidentiality. In sharing a patient’s case online for educational purposes, safeguarding identity becomes paramount. Removing names and changing minor details is insufficient, Michelson said.

“The patient-clinician relationship is sacred, and it can only be effective if patients have 100 percent confidence that all that happens with their clinician is kept in the strictest of confidence,” she said, adding that health care providers also should avoid obtaining information about their patients from social media because it can lead to bias and risk jeopardizing objectivity.

Academic clinicians can use social media as a recruitment tool to expand the pool of research participants for their studies, Michelson said. Because the majority of clinical research is conducted at academic medical centers, large segments of the population are excluded. “This affects the quality of the data and knowledge we gain from research,” she said.

Don S. Dizon, a professor of medicine and surgery at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, uses LinkedIn and Doximity, as well as Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, and most recently, YouTube and Post. He’s on Twitter nearly every day, where he interacts with the oncology community and his medical colleagues.

Also, he said, “I really like Instagram. It’s where you will see a hybrid of who I am professionally and personally. I’ve become comfortable sharing both up to a limit, but where else can I combine my appreciation of clothes with my professional life?” On that site, he’s seen sporting shirts with polka dots or stripes and an occasional bow-tie. He also posts photos of his cats.

Don S. Dizon, a professor of medicine and surgery at Brown, started using TikTok several years ago, telling medical stories in short-form videos.

Don S. Dizon

Dizon started using TikTok several years ago, telling medical stories in short-form videos. He may talk about an inspirational patient, his views on end-of-life care and death, or memories of people who have passed. But he is careful not to divulge any details that would identify anyone.

Recently, some people have become his patients after viewing his content on social media or on the Internet in general, which he clearly states isn’t a forum for medical advice. “In both situations, they are so much more relaxed when we meet, because it’s as if they have a sense of who I am as a person,” Dizon said. “I think that has helped so much in talking through a cancer diagnosis and a treatment plan, and yes, even discussions about prognosis.”

He also posts about equity and diversity. “I have found myself more likely to repost or react to issues that are inherently political, including racism, homophobia, transphobia and lack-of-access issues, because medicine is not isolated from society, and I truly believe that medicine is a social justice issue,” said Dizon, who is vice chair of diversity, equity, inclusion and professional integrity at the SWOG Cancer Research Network.

Through it all, Dizon likes “to break through the notion of doctor as infallible and all-knowing, the doctor as deity,” he said. “Humanizing what I do, especially in oncology, is something that challenges me on social media, and I appreciate the opportunities to do it on TikTok.”

Could this habit related to eating slow down rates of aging?

Previous research showed that restricting calories results in longer lives for mice, worms and flies. A new study by Columbia University researchers applied those findings to people. But what does this paper actually show?

Last Thursday, scientists at Columbia University published a new study finding that cutting down on calories could lead to longer, healthier lives. In the phase 2 trial, 220 healthy people without obesity dropped their calories significantly and, at least according to one test, their rate of biological aging slowed by 2 to 3 percent in over a couple of years. Small though that may seem, the researchers estimate that it would translate into a decline of about 10 percent in the risk of death as people get older. That's basically the same as quitting smoking.

Previous research has shown that restricting calories results in longer lives for mice, worms and flies. This research is unique because it applies those findings to people. It was published in Nature Aging.

But what did the researchers actually show? Why did two other tests indicate that the biological age of the research participants didn't budge? Does the new paper point to anything people should be doing for more years of healthy living? Spoiler alert: Maybe, but don't try anything before talking with a medical expert about it. I had the chance to chat with someone with inside knowledge of the research -- Dr. Evan Hadley, director of the National Institute of Aging's Division of Geriatrics and Clinical Gerontology, which funded the study. Dr. Hadley describes how the research participants went about reducing their calories, as well as the risks and benefits involved. He also explains the "aging clock" used to measure the benefits.

Evan Hadley, Director of the Division of Geriatrics and Clinical Gerontology at the National Institute of Aging

NIA