She Put the First Rover on Mars, Breaking the Glass Ceiling for Women at NASA

Donna Shirley pictured at her home in Tulsa, with a model of the Sojourner rover she was in charge of that explored Mars.

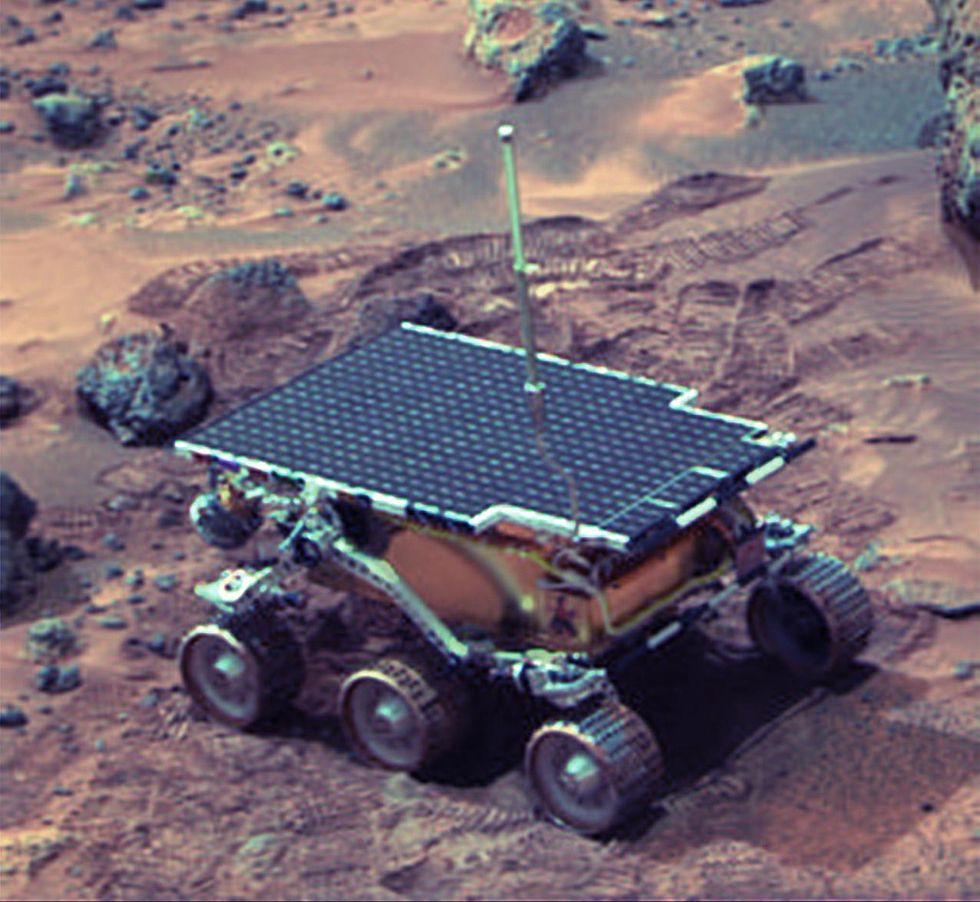

When NASA's Perseverance rover landed successfully on Mars on February 18, 2021, calling it "one giant leap for mankind" – as Neil Armstrong said when he set foot on the moon in 1969 – would have been inaccurate. This year actually marked the fifth time the U.S. space agency has put a remote-controlled robotic exploration vehicle on the Red Planet. And it was a female engineer named Donna Shirley who broke new ground for women in science as the manager of both the Mars Exploration Program and the 30-person team that built Sojourner, the first rover to land on Mars on July 4, 1997.

For Shirley, the Mars Pathfinder mission was the climax of her 32-year career at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. The Oklahoma-born scientist, who earned her Master's degree in aerospace engineering from the University of Southern California, saw her profile skyrocket with media appearances from CNN to the New York Times, and her autobiography Managing Martians came out in 1998. Now 79 and living in a Tulsa retirement community, she still embraces her status as a female pioneer.

"Periodically, I'll hear somebody say they got into the space program because of me, and that makes me feel really good," Shirley told Leaps.org. "I look at the mission control area, and there are a lot of women in there. I'm quite pleased I was able to break the glass ceiling."

Her $25-million, 25-pound microrover – powered by solar energy and designed to get rock samples and test soil chemistry for evidence of life – was named after Sojourner Truth, a 19th-century Black abolitionist and women's rights activist. Unlike Mars Pathfinder, Shirley didn't have to travel more than 131 million miles to reach her goal, but her path to scientific fame as a woman sometimes resembled an asteroid field.

The Sojourner Rover in 1997 on Mars.NASA/JPL

The Sojourner Rover in 1997 on Mars.NASA/JPLAs a high-IQ tomboy growing up in Wynnewood, Oklahoma (pop. 2,300), Shirley yearned to escape. She decided to become an engineer at age 10 and took flying lessons at 15. Her extraterrestrial aspirations were fueled by Ray Bradbury's The Martian Chronicles and Arthur C. Clarke's The Sands of Mars. Yet when she entered the University of Oklahoma (OU) in 1958, her freshman academic advisor initially told her: "Girls can't be engineers." She ignored him.

Years later, Shirley would combat such archaic thinking, succeeding at JPL with her creative, collaborative management style. "If you look at the literature, you'll find that teams that are either led by or heavily involved with women do better than strictly male teams," she noted.

However, her career trajectory stalled at OU. Burned out by her course load and distracted by a broken engagement to marry a fellow student, she switched her major to professional writing. After graduation, she applied her aeronautical background as a McDonnell Aircraft technical writer, but her boss, she says, harassed her and she faced gender-based hostility from male co-workers.

Returning to OU, Shirley finished off her engineering degree and became a JPL aerodynamist in 1966 after answering an ad in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. At first, she was the only female engineer among the research center's 2,000-odd engineers. She wore many hats, from designing planetary atmospheric entry vehicles to picking the launch date of November 4, 1973 for Mariner 10's mission to Venus and Mercury.

By the mid-1980's, she was managing teams that focused on robotics and Mars, delivering creative solutions when NASA budget cuts loomed. In 1989, the same year the Sojourner microrover concept was born, President George H.W. Bush announced his Space Exploration Initiative, including plans for a human mission to Mars by 2019.

That target, of course, wasn't attained, despite huge advances in technology and our understanding of the Martian environment. Today, Shirley believes humans could land on Mars by 2030. She became the founding director of the Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame in Seattle in 2004 after leaving NASA, and to this day, she enjoys checking out pop culture portrayals of Mars landings – even if they're not always accurate.

After the novel The Martian was published in 2011, which later was adapted into the hit film starring Matt Damon, Shirley phoned author Andy Weir: "You've got a major mistake in here. It says there's a storm that tries to blow the rocket over. But actually, the Mars atmosphere is so thin, it would never blow a rocket over!"

Fearlessly speaking her mind and seeking the stars helped Donna Shirley make history. However, a 2019 Washington Post story noted: "Women make up only about a third of NASA's workforce. They comprise just 28 percent of senior executive leadership positions and are only 16 percent of senior scientific employees." Whether it's traveling to Mars or trending toward gender equality, we've still got a long way to go.

A robot server, controlled remotely by a disabled worker, delivers drinks to patrons at the DAWN cafe in Tokyo.

A sleek, four-foot tall white robot glides across a cafe storefront in Tokyo’s Nihonbashi district, holding a two-tiered serving tray full of tea sandwiches and pastries. The cafe’s patrons smile and say thanks as they take the tray—but it’s not the robot they’re thanking. Instead, the patrons are talking to the person controlling the robot—a restaurant employee who operates the avatar from the comfort of their home.

It’s a typical scene at DAWN, short for Diverse Avatar Working Network—a cafe that launched in Tokyo six years ago as an experimental pop-up and quickly became an overnight success. Today, the cafe is a permanent fixture in Nihonbashi, staffing roughly 60 remote workers who control the robots remotely and communicate to customers via a built-in microphone.

More than just a creative idea, however, DAWN is being hailed as a life-changing opportunity. The workers who control the robots remotely (known as “pilots”) all have disabilities that limit their ability to move around freely and travel outside their homes. Worldwide, an estimated 16 percent of the global population lives with a significant disability—and according to the World Health Organization, these disabilities give rise to other problems, such as exclusion from education, unemployment, and poverty.

These are all problems that Kentaro Yoshifuji, founder and CEO of Ory Laboratory, which supplies the robot servers at DAWN, is looking to correct. Yoshifuji, who was bedridden for several years in high school due to an undisclosed health problem, launched the company to help enable people who are house-bound or bedridden to more fully participate in society, as well as end the loneliness, isolation, and feelings of worthlessness that can sometimes go hand-in-hand with being disabled.

“It’s heartbreaking to think that [people with disabilities] feel they are a burden to society, or that they fear their families suffer by caring for them,” said Yoshifuji in an interview in 2020. “We are dedicating ourselves to providing workable, technology-based solutions. That is our purpose.”

Shota, Kuwahara, a DAWN employee with muscular dystrophy, agrees. "There are many difficulties in my daily life, but I believe my life has a purpose and is not being wasted," he says. "Being useful, able to help other people, even feeling needed by others, is so motivational."

A woman receives a mammogram, which can detect the presence of tumors in a patient's breast.

When a patient is diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer, having surgery to remove the tumor is considered the standard of care. But what happens when a patient can’t have surgery?

Whether it’s due to high blood pressure, advanced age, heart issues, or other reasons, some breast cancer patients don’t qualify for a lumpectomy—one of the most common treatment options for early-stage breast cancer. A lumpectomy surgically removes the tumor while keeping the patient’s breast intact, while a mastectomy removes the entire breast and nearby lymph nodes.

Fortunately, a new technique called cryoablation is now available for breast cancer patients who either aren’t candidates for surgery or don’t feel comfortable undergoing a surgical procedure. With cryoablation, doctors use an ultrasound or CT scan to locate any tumors inside the patient’s breast. They then insert small, needle-like probes into the patient's breast which create an “ice ball” that surrounds the tumor and kills the cancer cells.

Cryoablation has been used for decades to treat cancers of the kidneys and liver—but only in the past few years have doctors been able to use the procedure to treat breast cancer patients. And while clinical trials have shown that cryoablation works for tumors smaller than 1.5 centimeters, a recent clinical trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York has shown that it can work for larger tumors, too.

In this study, doctors performed cryoablation on patients whose tumors were, on average, 2.5 centimeters. The cryoablation procedure lasted for about 30 minutes, and patients were able to go home on the same day following treatment. Doctors then followed up with the patients after 16 months. In the follow-up, doctors found the recurrence rate for tumors after using cryoablation was only 10 percent.

For patients who don’t qualify for surgery, radiation and hormonal therapy is typically used to treat tumors. However, said Yolanda Brice, M.D., an interventional radiologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, “when treated with only radiation and hormonal therapy, the tumors will eventually return.” Cryotherapy, Brice said, could be a more effective way to treat cancer for patients who can’t have surgery.

“The fact that we only saw a 10 percent recurrence rate in our study is incredibly promising,” she said.