This Special Music Helped Preemie Babies’ Brains Develop

Listening to music helped preterm babies' brains develop, according to the results of a new Swiss study.

Move over, Baby Einstein: New research from Switzerland shows that listening to soothing music in the first weeks of life helps encourage brain development in preterm babies.

For the study, the scientists recruited a harpist and a new-age musician to compose three pieces of music.

The Lowdown

Children who are born prematurely, between 24 and 32 weeks of pregnancy, are far more likely to survive today than they used to be—but because their brains are less developed at birth, they're still at high risk for learning difficulties and emotional disorders later in life.

Researchers in Geneva thought that the unfamiliar and stressful noises in neonatal intensive care units might be partially responsible. After all, a hospital ward filled with alarms, other infants crying, and adults bustling in and out is far more disruptive than the quiet in-utero environment the babies are used to. They decided to test whether listening to pleasant music could have a positive, counterbalancing effect on the babies' brain development.

Led by Dr. Petra Hüppi at the University of Geneva, the scientists recruited Swiss harpist and new-age musician Andreas Vollenweider (who has collaborated with the likes of Carly Simon, Bryan Adams, and Bobby McFerrin). Vollenweider developed three pieces of music specifically for the NICU babies, which were played for them five times per week. Each track was used for specific purposes: To help the baby wake up; to stimulate a baby who was already awake; and to help the baby fall back asleep.

When they reached an age equivalent to a full-term baby, the infants underwent an MRI. The researchers focused on connections within the salience network, which determines how relevant information is, and then processes and acts on it—crucial components of healthy social behavior and emotional regulation. The neural networks of preemies who had listened to Vollenweider's pieces were stronger than preterm babies who had not received the intervention, and were instead much more similar to full-term babies.

Next Up

The first infants in the study are now 6 years old—the age when cognitive problems usually become diagnosable. Researchers plan to follow up with more cognitive and socio-emotional assessments, to determine whether the effects of the music intervention have lasted.

The first infants in the study are now 6 years old—the age when cognitive problems usually become diagnosable.

The scientists note in their paper that, while they saw strong results in the babies' primary auditory cortex and thalamus connections—suggesting that they had developed an ability to recognize and respond to familiar music—there was less reaction in the regions responsible for socioemotional processing. They hypothesize that more time spent listening to music during a NICU stay could improve those connections as well; but another study would be needed to know for sure.

Open Questions

Because this initial study had a fairly small sample size (only 20 preterm infants underwent the musical intervention, with another 19 studied as a control group), and they all listened to the same music for the same amount of time, it's still undetermined whether variations in the type and frequency of music would make a difference. Are Vollenweider's harps, bells, and punji the runaway favorite, or would other styles of music help, too? (Would "Baby Shark" help … or hurt?) There's also a chance that other types of repetitive sounds, like parents speaking or singing to their children, might have similar effects.

But the biggest question is still the one that the scientists plan to tackle next: Whether the intervention lasts as the children grow up. If it does, that's great news for any family with a preemie — and for the baby-sized headphone industry.

Is Red Tape Depriving Patients of Life-Altering Therapies?

Medical treatment represented on a world map.

Rich Mancuso suffered from herpes for most of his adult life. The 49-year-old New Jersey resident was miserable. He had at least two to three outbreaks every month with painful and unsightly sores on his face and in his eyes, yet the drugs he took to control the disease had terrible side effects--agonizing headaches and severe stomach disturbances.

Last week, the FDA launched a criminal investigation to determine whether the biotech behind the vaccine had violated regulations.

So in 2016, he took an unusual step: he was flown to St. Kitt's, an island in the West Indies, where he participated in a clinical trial of a herpes vaccine, and received three injections of the experimental therapeutic during separate visits to the island. Within a year, his outbreaks stopped. "Nothing else worked," says Mancuso, who feels like he's gotten his life back. "And I've tried everything on the planet."

Mancuso was one of twenty genital herpes sufferers who were given the experimental vaccine in tests conducted on the Caribbean island and in hotel rooms near the campus of Southern Illinois University in Springfield where the vaccine's developer, microbiologist William Halford, was on the faculty. But these tests were conducted under the radar, without the approval or safety oversight of the Food and Drug Administration or an institutional review board (IRB), which routinely monitor human clinical trials of experimental drugs to make sure participants are protected.

Last week, the FDA launched a criminal investigation to determine whether anyone from SIU or Rational Vaccines, the biotech behind the vaccine, had violated regulations by aiding Halford's research. The SIU scientist was a microbiologist, not a medical doctor, which means that volunteers were not only injected with an unsanctioned experimental treatment but there wasn't even routine medical oversight.

On one side are scientists and government regulators with legitimate safety concerns....On the other are desperate patients and a dying scientist willing to go rogue in a foreign country.

Halford, who was stricken with a rare form of a nasal cancer, reportedly bypassed regulatory rules because the clock was ticking and he wanted to speed this potentially life-altering therapeutic to patients. "There was no way he had enough time to raise $100 million to test the drugs in the U.S.," says Mancuso, who became friends with Halford before he died in June of 2017 at age 48. "He knew if he didn't do something, his work would just die and no one would benefit. This was the only way."

But was it the only way? Once the truth about the trial came to light, public health officials in St. Kitt's disavowed the trial, saying they had not been notified that it was happening, and Southern Illinois University's medical school launched an investigation that ultimately led to the resignation of three employees, including a faculty member, a graduate student and Halford's widow. Investors in Rational Vaccines, including maverick Silicon Valley billionaire Peter Thiel, demanded that all FDA rules must be followed in future tests.

"Trials have to yield data that can be submitted to the FDA, which means certain requirements have to be met," says Jeffrey Kahn, a bioethicist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. "These were renegade researchers who exposed people to unnecessary risks, which was hugely irresponsible. I don't know what they expected to do with the research. It was a waste of money and generated data that can't be used because no regulator would accept it."

But this story illuminates both sides of a thorny issue. On one side are scientists and government regulators with legitimate safety concerns who want to protect volunteers from very real risks—people have died even in closely monitored clinical trials. On the other, are desperate patients and a dying scientist willing to go rogue in a foreign country where there is far less regulatory scrutiny. "It's a balancing act," says Jennifer Miller, a medical ethicist at New York University and president of Bioethics International. "You really need to protect participants but you also want access to safe therapies."

"Safety is important, but being too cautious kills people, too—allowing them to just die without intervention seems to be the biggest harm."

This requirement—that tests show a drug is safe and effective before it can win regulatory approval--dates back to 1962, when the sedative thalidomide was shown to have caused thousands of birth defects in Europe. But clinical trials can be costly and often proceed at a glacial pace. Typically, companies shell out more than $2.5 billion over the course of the decade it normally takes to shepherd a new treatment through the three phases of testing before it wins FDA approval, according to a 2014 study by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development. Yet only 11.8 percent of experimental therapies entering clinical tests eventually cross the finish line.

The upshot is that millions can suffer and thousands of people may die awaiting approvals for life saving drugs, according to Elizabeth Parrish, the founder and CEO of BioViva, a Seattle-based biotech that aims to provide data collection platforms to scientists doing overseas tests. "Going offshore to places where it's legal to take a therapeutic can created expedited routes for patients to get therapies for which there is a high level of need," she says. "Safety is important, but being too cautious kills people, too—allowing them to just die without intervention seems to be the biggest harm."

Parrish herself was frustrated with the slow pace of gene therapy trials; scientists worried about the risks associated with fixing mutant DNA. To prove a point, she traveled to a clinic in Colombia in 2015 where she was injected with two gene therapies that aim to improve muscle function and lengthen telomeres, the caps on the end of chromosomes that are linked to aging and genetic diseases. Six months later, the therapy seemed to have worked—her muscle mass had increased and her telomeres had grown by 9 percent, the equivalent of turning back 20 years of aging, according to her own account. Yet the treatments are still unavailable here in the U.S.

In the past decade, Latin American countries like Columbia, and Mexico in particular, have become an increasingly attractive test destination for multi-national drug companies and biotechs because of less red tape.

In the past decade, Latin American countries like Columbia, and Mexico in particular, have become an increasingly attractive test destination for multi-national drug companies and biotechs because of less red tape around testing emerging new science, like gene therapies or stem cells. Plus, clinical trials are cheaper to conduct, it's easier to recruit volunteers, especially ones who are treatment naïve, and these human tests can reveal whether local populations actually respond to a particular therapy. "We do have an exhaustive framework for running clinical trials that are aligned with international requirements," says Ernesto Albaga, an attorney with Hogan Lovells in Mexico City who specializes in the life sciences. "But our environment is still not as stringent as it is in other places, like the U.S."

The fact is American researchers are increasingly testing experimental drugs outside of the U.S., although virtually all of them are monitored by local scientists who serve as co-investigators. In 2017 alone, more than 86 percent of experimental drugs seeking FDA approval have been tested, at least in part, in foreign countries, like Mexico, China, Russia, Poland and South Africa, according to an analysis by STAT. However, in places without strict oversight, such as Russia and Georgia, results may be fraudulent, according to one 2017 report in the New England Journal of Medicine. And in developing countries, the poor can become guinea pigs. In the early 2000s, for example, a test in Uganda of an AIDS drug resulted in thousands of unreported serious adverse reactions and 14 deaths; in India, eight volunteers died during a test of the anti-clotting drug, Streptokinase—and test subjects didn't even know they were part of a clinical trials.

Still, "the world is changing," concludes Dr. Jennifer Miller of NYU. "We need to figure out how to get safe and effective drugs to patients more quickly without sacrificing too much protection."

This App Helps Diagnose Rare Genetic Disorders from a Picture

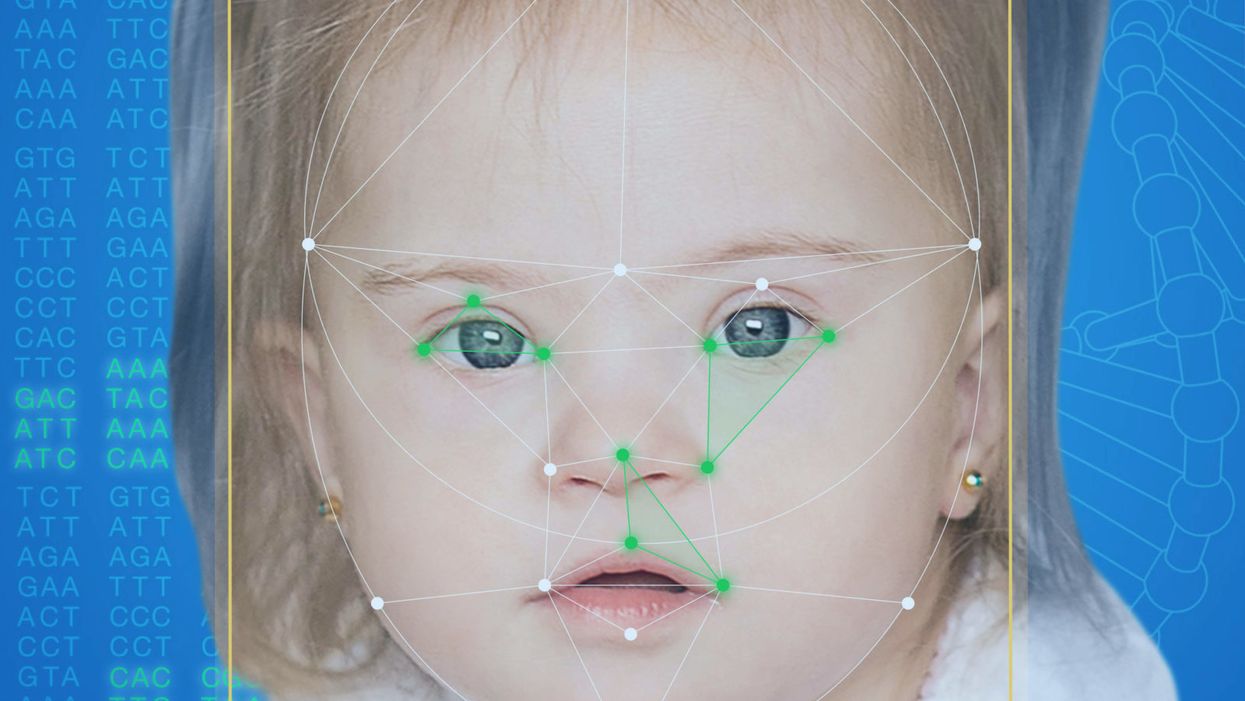

FDNA's Face2Gene technology analyzes patient biometric data using artificial intelligence, identifying correlations with disease-causing genetic variations.

Medical geneticist Omar Abdul-Rahman had a hunch. He thought that the three-year-old boy with deep-set eyes, a rounded nose, and uplifted earlobes might have Mowat-Wilson syndrome, but he'd never seen a patient with the rare disorder before.

"If it weren't for the app I'm not sure I would have had the confidence to say 'yes you should spend $1000 on this test."

Rahman had already ordered genetic tests for three different conditions without any luck, and he didn't want to cost the family any more money—or hope—if he wasn't sure of the diagnosis. So he took a picture of the boy and uploaded the photo to Face2Gene, a diagnostic aid for rare genetic disorders. Sure enough, Mowat-Wilson came up as a potential match. The family agreed to one final genetic test, which was positive for the syndrome.

"If it weren't for the app I'm not sure I would have had the confidence to say 'yes you should spend $1000 on this test,'" says Rahman, who is now the director of Genetic Medicine at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, but saw the boy when he was in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in 2012.

"Families who are dealing with undiagnosed diseases never know what's going to come around the corner, what other organ system might be a problem next week," Rahman says. With a diagnosis, "You don't have to wait for the other shoe to drop because now you know the extent of the condition."

A diagnosis is the first and most important step for patients to attain medical care. Disease prognosis, treatment plans, and emotional coping all stem from this critical phase. But diagnosis can also be the trickiest part of the process, particularly for rare disorders. According to one European survey, 40 percent of rare diseases are initially misdiagnosed.

Healthcare professionals and medical technology companies hope that facial recognition software will help prevent families from facing difficult disruptions due to misdiagnoses.

"Patients with rare diseases or genetic disorders go through a long period of diagnostic odyssey, and just putting a name to a syndrome or finding a diagnosis can be very helpful and relieve a lot of tension for the family," says Dekel Gelbman, CEO of FDNA.

Consequently, a misdiagnosis can be devastating for families. Money and time may have been wasted on fruitless treatments, while opportunities for potentially helpful therapies or clinical trials were missed. Parents led down the wrong path must change their expectations of their child's long-term prognosis and care. In addition, they may be misinformed regarding future decisions about family planning.

Healthcare professionals and medical technology companies hope that facial recognition software will help prevent families from facing these difficult disruptions by improving the accuracy and ease of diagnosing genetic disorders. Traditionally, doctors diagnose these types of conditions by identifying unique patterns of facial features, a practice called dysmorphology. Trained physicians can read a child's face like a map and detect any abnormal ridges or plateaus—wide-set eyes, broad forehead, flat nose, rotated ears—that, combined with other symptoms such as intellectual disability or abnormal height and weight, signify a specific genetic disorder.

These morphological changes can be subtle, though, and often only specialized medical geneticists are able to detect and interpret these facial clues. What's more, some genetic disorders are so rare that even a specialist may not have encountered it before, much less a general practitioner. Diagnosing rare conditions has improved thanks to genomic testing that can confirm (or refute) a doctor's suspicion. Yet with thousands of variants in each person's genome, identifying the culprit mutation or deletion can be extremely difficult if you don't know what you're looking for.

Facial recognition technology is trying to take some of the guesswork out of this process. Software such as the Face2Gene app use machine learning to compare a picture of a patient against images of thousands of disorders and come back with suggestions of possible diagnoses.

"This is a classic field for artificial intelligence because no human being can really have enough knowledge and enough experience to be able to do this for thousands of different disorders."

"When we met a geneticist for the first time we were pretty blown away with the fact that they actually use their own human pattern recognition" to diagnose patients, says Gelbman. "This is a classic field for AI [artificial intelligence], for machine learning because no human being can really have enough knowledge and enough experience to be able to do this for thousands of different disorders."

When a physician uploads a photo to the app, they are given a list of different diagnostic suggestions, each with a heat map to indicate how similar the facial features are to a classic representation of the syndrome. The physician can hone the suggestions by adding in other symptoms or family history. Gelbman emphasized that the app is a "search and reference tool" and should not "be used to diagnose or treat medical conditions." It is not approved by the FDA as a diagnostic.

"As a tool, we've all been waiting for this, something that can help everyone," says Julian Martinez-Agosto, an associate professor in human genetics and pediatrics at UCLA. He sees the greatest benefit of facial recognition technology in its ability to empower non-specialists to make a diagnosis. Many areas, including rural communities or resource-poor countries, do not have access to either medical geneticists trained in these types of diagnostics or genomic screens. Apps like Face2Gene can help guide a general practitioner or flag diseases they might not be familiar with.

One concern is that most textbook images of genetic disorders come from the West, so the "classic" face of a condition is often a child of European descent.

Maximilian Muenke, a senior investigator at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), agrees that in many countries, facial recognition programs could be the only way for a doctor to make a diagnosis.

"There are only geneticists in countries like the U.S., Canada, Europe, Japan. In most countries, geneticists don't exist at all," Muenke says. "In Nigeria, the most populous country in all of Africa with 160 million people, there's not a single clinical geneticist. So in a country like that, facial recognition programs will be sought after and will be extremely useful to help make a diagnosis to the non-geneticists."

One concern about providing this type of technology to a global population is that most textbook images of genetic disorders come from the West, so the "classic" face of a condition is often a child of European descent. However, the defining facial features of some of these disorders manifest differently across ethnicities, leaving clinicians from other geographic regions at a disadvantage.

"Every syndrome is either more easy or more difficult to detect in people from different geographic backgrounds," explains Muenke. For example, "in some countries of Southeast Asia, the eyes are slanted upward, and that happens to be one of the findings that occurs mostly with children with Down Syndrome. So then it might be more difficult for some individuals to recognize Down Syndrome in children from Southeast Asia."

There is a risk that providing this type of diagnostic information online will lead to parents trying to classify their own children.

To combat this issue, Muenke helped develop the Atlas of Human Malformation Syndromes, a database that incorporates descriptions and pictures of patients from every continent. By providing examples of rare genetic disorders in children from outside of the United States and Europe, Muenke hopes to provide clinicians with a better understanding of what to look for in each condition, regardless of where they practice.

There is a risk that providing this type of diagnostic information online will lead to parents trying to classify their own children. Face2Gene is free to download in the app store, although users must be authenticated by the company as a healthcare professional before they can access the database. The NHGRI Atlas can be accessed by anyone through their website. However, Martinez and Muenke say parents already use Google and WebMD to look up their child's symptoms; facial recognition programs and databases are just an extension of that trend. In fact, Martinez says, "Empowering families is another way to facilitate access to care. Some families live in rural areas and have no access to geneticists. If they can use software to get a diagnosis and then contact someone at a large hospital, it can help facilitate the process."

Martinez also says the app could go further by providing greater transparency about how the program makes its assessments. Giving clinicians feedback about why a diagnosis fits certain facial features would offer a valuable teaching opportunity in addition to a diagnostic aid.

Both Martinez and Muenke think the technology is an innovation that could vastly benefit patients. "In the beginning, I was quite skeptical and I could not believe that a machine could replace a human," says Muenke. "However, I am a convert that it actually can help tremendously in making a diagnosis. I think there is a place for facial recognition programs, and I am a firm believer that this will spread over the next five years."