Wild-Caught Seafood Has Been Notoriously Shady – Until Now

The Dock to Dish model has expanded across North and Central America. Above, artisanal fishermen on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica head out to sea seeking schools of abundant forage fish to supply the program.

In 2012, entrepreneur Sean Barrett founded Dock to Dish in Montauk, New York. It connected local fishermen and women with local chefs, enabling the chefs to serve hyper-fresh seafood – with the caveat that they didn't know what would be on their menus until it arrived in their kitchens the night before.

"Since we're not a seafood-centric culture, people don't know what's what, where fish are from, and when they're in season, making them easy to dupe."

In June of 2017, The United Nations Foundation designated Dock to Dish as one of the top breakthrough innovations that can scale to solve the ocean's grand challenges. His company has since expanded across the Americas and has just opened up shop in Fiji. Leapsmag recently chatted with Barrett about his inspirations and ideas for how to overcome the hurdles of farming wild seafood. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What inspired you to start Dock to Dish?

The short story is "A Tale of Two Hills."

The first is Quail Hill Farm in Amagansett. I grew up in the commercial fishing port of Chinicock in the 1980's and 90's, working on my family's dock from an early age and in the restaurant industry in my teens. By my thirties, I had accrued my 10,000 hours of experience in both dock and dish. I watched the food system shift from local to global, especially in seafood. By the early 2000's, over 90 percent of seafood in the U.S. was imported. It was bad.

Quail Hill was the first CSA [Community Supported Agriculture, in which customers pay up front for a share in whatever crops grow (or don't) on the farm that season] in the U.S., founded in 1990. So people in the area were accustomed to getting their produce that way. Scott Chaskey, the poet farmer at Quail Hill, really helped crystallize the philosophy for me and inspired me to apply it to seafood. Fishermen had always been bringing a share of their day's catch to their neighbors; now we were just doing it in a more formalized way.

The second is Blue Hill at Stone Barns. [Executive chef and co-owner] Dan Barber literally trademarked the phrase "Know Thy Farmer"; we just expanded it to Know Thy Fisherman and it took off like a rocket ship. His connections in the restaurant world were also indispensable.

17th generation Montauk fisherman Captain Bruce Beckwith (above left) with crew Charlie Etzel (Center) and Jeremy Gould (right).

Do you have any issues that are unique to seafood that a CSA or meat co-op wouldn't face?

This food is WILD. People are totally disconnected from what that word means, and it makes seafood different from everything else. Everything changes when viewed through the prism of that word.

This is the last wild food we eat. It is unpredictable, and subject to variables ranging from currents and tides to which way the wind is blowing. But it is what makes our model so much more impactful and beneficial than the industrialized, demand-driven marketplace that surrounds us. The ocean and its ecosystem are the boss, not chefs and consumers.

There has a been a lot of press about seafood being mislabeled. How and why does that happen? Can Dock to Dish fix it?

Imported, farmed seafood is cheap. Wild, sustainable seafood is not. People are buying low and selling high to make a buck; and while fisheries are extraordinarily regulated, the marketplace isn't. There is no punishment for mislabeling, and no means to correct it. Since we're not a seafood-centric culture, people don't know what's what, where fish are from, and when they're in season, making them easy to dupe. But technology is poised to fix that; DNA testing can test what a fish sample is and where it's from, and SciO handheld spectrometers – soon to be incorporated into smartphones – can analyze the molecular makeup of anything on your plate.

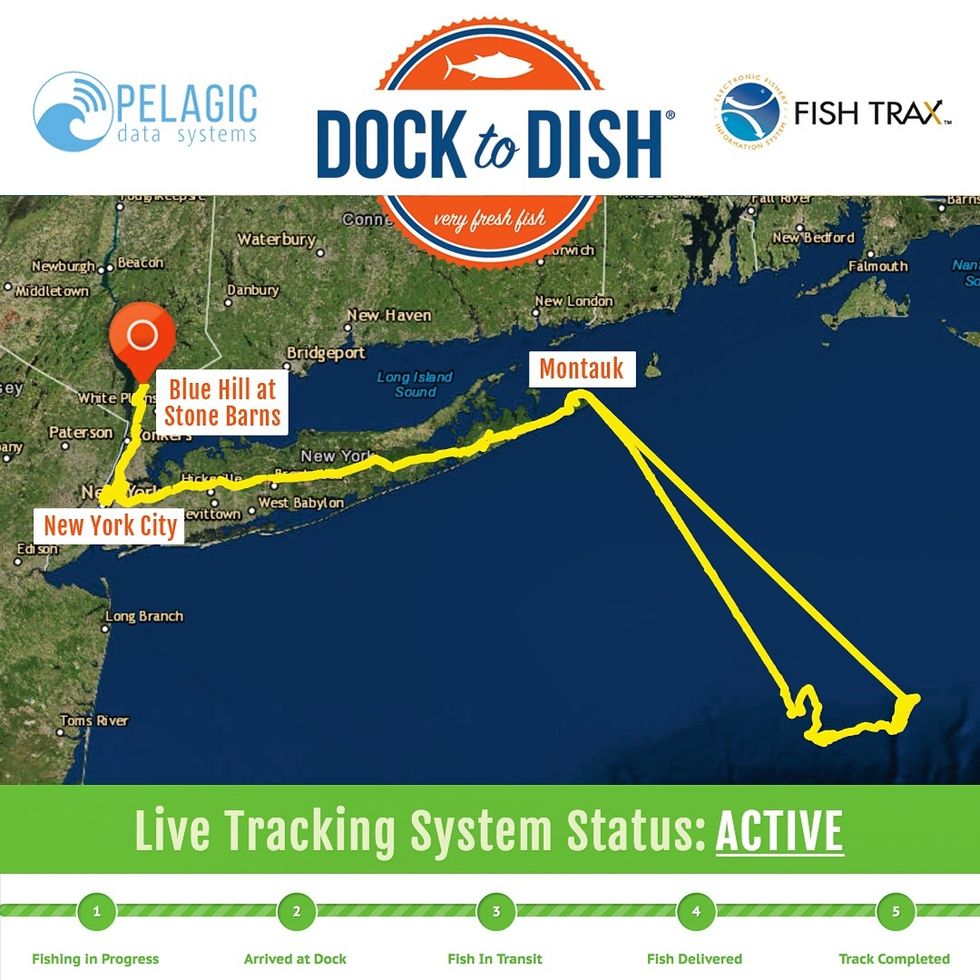

We've created the first ever live tracking system and database for wild fisheries. It is similar to the electronic system used to monitor commercial fisheries, thanks to which the resurgence of wild seafood in U.S. waters is a model for the rest of the world. We have vessel tracking devices on our fishing boats and delivery vans, so the path of each fish is publicly available in real time.

In 2017, Dock to Dish launched the world's first live "end-to-end" tracking system for wild seafood, which provides full chain transparency and next-generation traceability for members.

People are increasingly looking to seafood as a healthier, possibly more sustainable protein option than meat. Can Dock to Dish scale up to accommodate this potentially growing market?

Nope. We can't scale; the supply is finite. That's why the price keeps going up. To avoid becoming "fish for the rich" we are working closely with Greenwave.org to create a network of 3D restorative ocean farms growing kelp and shellfish, which sequester carbon and nitrogen out of the air and soil. Restorative, because sustainable is no longer an option. In fifty years, a plate of seafood will be mostly ocean vegetables with a small amount of finfish as a garnish.

DNA- and RNA-based electronic implants may revolutionize healthcare

The test tubes contain tiny DNA/enzyme-based circuits, which comprise TRUMPET, a new type of electronic device, smaller than a cell.

Implantable electronic devices can significantly improve patients’ quality of life. A pacemaker can encourage the heart to beat more regularly. A neural implant, usually placed at the back of the skull, can help brain function and encourage higher neural activity. Current research on neural implants finds them helpful to patients with Parkinson’s disease, vision loss, hearing loss, and other nerve damage problems. Several of these implants, such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink, have already been approved by the FDA for human use.

Yet, pacemakers, neural implants, and other such electronic devices are not without problems. They require constant electricity, limited through batteries that need replacements. They also cause scarring. “The problem with doing this with electronics is that scar tissue forms,” explains Kate Adamala, an assistant professor of cell biology at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. “Anytime you have something hard interacting with something soft [like muscle, skin, or tissue], the soft thing will scar. That's why there are no long-term neural implants right now.” To overcome these challenges, scientists are turning to biocomputing processes that use organic materials like DNA and RNA. Other promised benefits include “diagnostics and possibly therapeutic action, operating as nanorobots in living organisms,” writes Evgeny Katz, a professor of bioelectronics at Clarkson University, in his book DNA- And RNA-Based Computing Systems.

While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output.

Adamala’s research focuses on developing such biocomputing systems using DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids. Using these molecules in the biocomputing systems allows the latter to be biocompatible with the human body, resulting in a natural healing process. In a recent Nature Communications study, Adamala and her team created a new biocomputing platform called TRUMPET (Transcriptional RNA Universal Multi-Purpose GatE PlaTform) which acts like a DNA-powered computer chip. “These biological systems can heal if you design them correctly,” adds Adamala. “So you can imagine a computer that will eventually heal itself.”

The basics of biocomputing

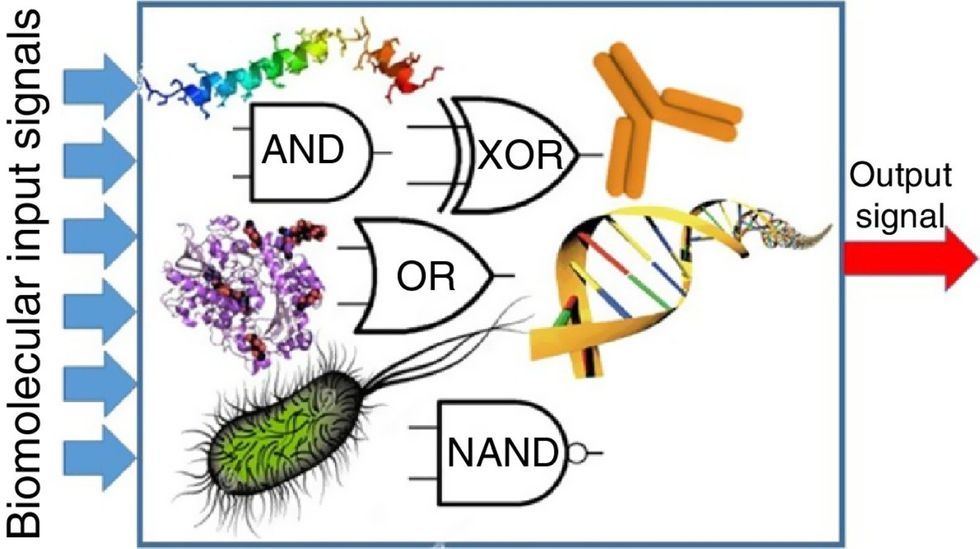

Biocomputing and regular computing have many similarities. Like regular computing, biocomputing works by running information through a series of gates, usually logic gates. A logic gate works as a fork in the road for an electronic circuit. The input will travel one way or another, giving two different outputs. An example logic gate is the AND gate, which has two inputs (A and B) and two different results. If both A and B are 1, the AND gate output will be 1. If only A is 1 and B is 0, the output will be 0 and vice versa. If both A and B are 0, the result will be 0. While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output. In this case, the DNA enters the logic gate as a single or double strand.

If the DNA is double-stranded, the system “digests” the DNA or destroys it, which results in non-fluorescence or “0” output. Conversely, if the DNA is single-stranded, it won’t be digested and instead will be copied by several enzymes in the biocomputing system, resulting in fluorescent RNA or a “1” output. And the output for this type of binary system can be expanded beyond fluorescence or not. For example, a “1” output might be the production of the enzyme insulin, while a “0” may be that no insulin is produced. “This kind of synergy between biology and computation is the essence of biocomputing,” says Stephanie Forrest, a professor and the director of the Biodesign Center for Biocomputing, Security and Society at Arizona State University.

Biocomputing circles are made of DNA, RNA, proteins and even bacteria.

Evgeny Katz

The TRUMPET’s promise

Depending on whether the biocomputing system is placed directly inside a cell within the human body, or run in a test-tube, different environmental factors play a role. When an output is produced inside a cell, the cell's natural processes can amplify this output (for example, a specific protein or DNA strand), creating a solid signal. However, these cells can also be very leaky. “You want the cells to do the thing you ask them to do before they finish whatever their businesses, which is to grow, replicate, metabolize,” Adamala explains. “However, often the gate may be triggered without the right inputs, creating a false positive signal. So that's why natural logic gates are often leaky." While biocomputing outside a cell in a test tube can allow for tighter control over the logic gates, the outputs or signals cannot be amplified by a cell and are less potent.

TRUMPET, which is smaller than a cell, taps into both cellular and non-cellular biocomputing benefits. “At its core, it is a nonliving logic gate system,” Adamala states, “It's a DNA-based logic gate system. But because we use enzymes, and the readout is enzymatic [where an enzyme replicates the fluorescent RNA], we end up with signal amplification." This readout means that the output from the TRUMPET system, a fluorescent RNA strand, can be replicated by nearby enzymes in the platform, making the light signal stronger. "So it combines the best of both worlds,” Adamala adds.

These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body.

The TRUMPET biocomputing process is relatively straightforward. “If the DNA [input] shows up as single-stranded, it will not be digested [by the logic gate], and you get this nice fluorescent output as the RNA is made from the single-stranded DNA, and that's a 1,” Adamala explains. "And if the DNA input is double-stranded, it gets digested by the enzymes in the logic gate, and there is no RNA created from the DNA, so there is no fluorescence, and the output is 0." On the story's leading image above, if the tube is "lit" with a purple color, that is a binary 1 signal for computing. If it's "off" it is a 0.

While still in research, TRUMPET and other biocomputing systems promise significant benefits to personalized healthcare and medicine. These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body. The study’s lead author and graduate student Judee Sharon is already beginning to research TRUMPET's ability for earlier cancer diagnoses. Because the inputs for TRUMPET are single or double-stranded DNA, any mutated or cancerous DNA could theoretically be detected from the platform through the biocomputing process. Theoretically, devices like TRUMPET could be used to detect cancer and other diseases earlier.

Adamala sees TRUMPET not only as a detection system but also as a potential cancer drug delivery system. “Ideally, you would like the drug only to turn on when it senses the presence of a cancer cell. And that's how we use the logic gates, which work in response to inputs like cancerous DNA. Then the output can be the production of a small molecule or the release of a small molecule that can then go and kill what needs killing, in this case, a cancer cell. So we would like to develop applications that use this technology to control the logic gate response of a drug’s delivery to a cell.”

Although platforms like TRUMPET are making progress, a lot more work must be done before they can be used commercially. “The process of translating mechanisms and architecture from biology to computing and vice versa is still an art rather than a science,” says Forrest. “It requires deep computer science and biology knowledge,” she adds. “Some people have compared interdisciplinary science to fusion restaurants—not all combinations are successful, but when they are, the results are remarkable.”

Crickets are low on fat, high on protein, and can be farmed sustainably. They are also crunchy.

In today’s podcast episode, Leaps.org Deputy Editor Lina Zeldovich speaks about the health and ecological benefits of farming crickets for human consumption with Bicky Nguyen, who joins Lina from Vietnam. Bicky and her business partner Nam Dang operate an insect farm named CricketOne. Motivated by the idea of sustainable and healthy protein production, they started their unconventional endeavor a few years ago, despite numerous naysayers who didn’t believe that humans would ever consider munching on bugs.

Yet, making creepy crawlers part of our diet offers many health and planetary advantages. Food production needs to match the rise in global population, estimated to reach 10 billion by 2050. One challenge is that some of our current practices are inefficient, polluting and wasteful. According to nonprofit EarthSave.org, it takes 2,500 gallons of water, 12 pounds of grain, 35 pounds of topsoil and the energy equivalent of one gallon of gasoline to produce one pound of feedlot beef, although exact statistics vary between sources.

Meanwhile, insects are easy to grow, high on protein and low on fat. When roasted with salt, they make crunchy snacks. When chopped up, they transform into delicious pâtes, says Bicky, who invents her own cricket recipes and serves them at industry and public events. Maybe that’s why some research predicts that edible insects market may grow to almost $10 billion by 2030. Tune in for a delectable chat on this alternative and sustainable protein.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Further reading:

More info on Bicky Nguyen

https://yseali.fulbright.edu.vn/en/faculty/bicky-n...

The environmental footprint of beef production

https://www.earthsave.org/environment.htm

https://www.watercalculator.org/news/articles/beef-king-big-water-footprints/

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00005/full

https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-footprint-food-methane

Insect farming as a source of sustainable protein

https://www.insectgourmet.com/insect-farming-growing-bugs-for-protein/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/insect-farming

Cricket flour is taking the world by storm

https://www.cricketflours.com/

https://talk-commerce.com/blog/what-brands-use-cricket-flour-and-why/

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.